Introduction↑

The Western Front drew the entire world’s attention in early 1918. After pulling multiple divisions from the Eastern Front and training their soldiers in storm trooper tactics between late 1917 and early 1918, the Germans launched their infamous spring offensives. The Russian Revolutions altered the situation on the Eastern Front and gave the Germans the opportunity to take one last fateful gamble to win the war before the mass of American troops arrived to sway the outcome.

The United States’ entry into the war more than counterbalanced the exit of tsarist Russia from the conflict. President Woodrow Wilson’s (1856-1924) Fourteen Points fed into subversive and revolutionary nationalistic movements that proved fatal to the Habsburg troops on the front lines as well as on the home front. It did not help that Point Ten of Wilson’s Fourteen Points, which emphasized self-determination, was aimed specifically at Austria-Hungary. In time, the failure to federalize the Dual Monarchy or find another solution to the nationality issue resulted in the Empire’s dismemberment.

As the war progressed, the British (Entente) blockade strangled the Central Powers, creating misery and economic turmoil. The blockade produced many deaths and mass starvation, increasing the peoples’ war-weariness and popular unrest. Living conditions obviously suffered as material exhaustion accelerated. Quality food became more difficult to obtain, leading to widespread malnutrition and, ultimately, mass starvation. The announcement of further rationing in early January 1918 resulted in the outbreak of strikes that swept through the Dual Monarchy as war-weariness and despair increased. These internal Habsburg conditions weakened its negotiating position at the Brest-Litovsk meeting. The government’s failure to provide domestic leadership resulted in political confusion and provoked negative, nationalist responses to Vienna’s governance. Meanwhile, the patriotic feeling that had prevailed in Germany collapsed owing to increased civilian starvation and economic hardship.

A series of treaties in early 1918 allowed German and Habsburg forces to consolidate their gains in Eastern Europe. Germany signed the “Bread Peace” with Ukraine on 2 February and occupied Kiev on 1 March. The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, negotiated with Russia’s new Bolshevik government, followed on 3 March and established German hegemony in Central and Eastern Europe. The occupation of Ukraine, however, did not provide the food quantities needed to quell the hunger riots breaking out in both Germany and Austria-Hungary. Workers and soldiers had been reduced to walking skeletons; more than a quarter million Germans ultimately died of malnutrition during 1918. By October, rail transport of food supplies had collapsed in Austria-Hungary.

With Russia finally eliminated from the war in 1917, the Habsburg Supreme Command was free to transfer fifty-three divisions and assorted reserve units to the Italian front. Unfortunately, the redeployed forces lacked much of their artillery complement, as only one-third of the necessary horses survived to transport the guns. Locomotives increasingly broke down due to poor maintenance and a shortage of necessary parts and coal, making it difficult to transport troops to the new front.[1]

During early 1918, the activities of several national groups within Austria-Hungary became troublesome enough to warrant military intervention. Strikes, demonstrations, and looting, for example, occurred throughout Bohemia and Moravia. Seven front-line Habsburg infantry divisions (41,000 soldiers) were deployed to the homeland to preserve internal security and to track down army deserters. During the first half of 1918, the increased military presence proved sufficient to suppress the early nationalistic demonstrations and uprisings that occurred in Bohemia. Later it would not.

The German General Staff realized that their armies had to rapidly launch a major “last card” offensive operation before American troops swamped the Western Front. Despite assembling vast numbers of troops and outnumbering Entente infantry divisions, the Germans possessed far fewer airplanes, artillery pieces, tanks, and trucks than their opponents.

Indications of morale problems in the Germany army became difficult to ignore. “Shirking” became a major concern as training and preparations commenced for the anticipated German offensives in 1918. Some estimates placed the number of German “shirkers” at up to 1 million soldiers on the Western Front.[2] It was hoped that the offensives would achieve battlefield success before American troops appeared in overwhelming numbers.

As military defeat loomed for Germany, revolutionary groups increased their activity within the German army and naval fleet. German workers became more politically active and more likely to take part in radical movements. The accelerating problem of food shortages, owing to low production and poor distribution, affected the starving population. Securing an adequate food supply was a critical factor on the home front throughout the entire war.

The German Spring Offensives↑

The long-anticipated first German spring offensive, Operation Michael (Kaiserschlacht), commenced on 21 March 1918. Seventy-four German divisions supported by 6,500 artillery pieces and 730 aircraft attacked thirty-four British infantry and three cavalry division forces on a fifty-mile front on the 1916 Somme battleground. Although the terrain had been badly damaged from the Somme battles and the 1917 Nivelle Offensive, the Germans managed to drive the British back forty miles. On 25 March, the attacking forces refocused their attention from the flanks to the center and right flank of the German lines, with a new objective of Arras. However, the rapidly advancing Germans quickly outran their supply lines and lacked the necessary reserve formations because of the heavy casualties they sustained. Artillery was also unable to keep pace with the advancing troops due to the terrible terrain. The battle ended on 5 April with the attacking German troops exhausted. They had lost 239,000 of their best storm troopers in the operation. Although the Germans recaptured almost all of the territory they had lost in 1916, they could not exploit their breakthrough, as they lacked the necessary reserve units. The battle thus produced a great tactical success, but provided little strategic advantage.

During the second German offensive, Operation Georgette, the German army struggled north toward Flanders just south of the battlefield at Ypres. The German army attempted to destroy the entrenched British army as the battle raged between 19 and 21 April. The British retreated fifteen to twenty miles, but their lines ultimately held. Once again exhausted, stretched thin, and unable to transport their artillery forward rapidly enough, the Germans broke off the offensive and regrouped.

A third offensive effort lasted from 27 May to 3 June, by which time American troops had joined the front lines in large numbers. The Germans sought to obtain a final, decisive victory by attacking the junction between the British and French lines in an attempt to drive the British back to the Channel ports. The Germans also launched a diversionary attack against the French to bind their troops at the Chemin des Dames. A 160-minute massive artillery barrage battered the French lines. By the end of May, German troops had reached the Marne River Valley, the natural route to Paris, just fifty miles away. However, once again they outran their supply lines and extended their front lines with the enlarged salient their operations had produced.

During the third offensive, the newly conquered salient made it not only difficult to supply German troops, but also to defend the newly extended front lines. The Germans had again achieved tremendous advances, but, as in earlier operations, proved unable to exploit their gains. Their casualties had reached 600,000 irreplaceable trained assault troops.

German forces next sought to link their salient north along the Somme River with their salient south of the Marne River. A successful action would have shortened the German lines, but the French commander anticipated the attack. On 9 June, the first battle day, a spectacular six-mile advance occurred, but the French launched a counterattack on 11 June to cut the offensive short. The German front had become destabilized. A month would go by before the Germans could mount another offensive operation. The lull proved invaluable to the Allies as more American troops deployed along the front lines.

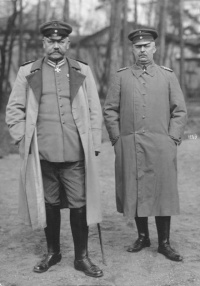

The fifth German spring offensive objective was Champagne-Marne. Often designated the Second Battle of the Marne, the operation lasted from 15 July to 18 August. It was during this engagement, however, that strategic initiative shifted from the Germans to the British and French. By the end of July, the overall military advantage had swung against the Central Powers. At a meeting at Spa on 13-14 August, Generals Paul von Hindenburg (1847-1934) and Erich Ludendorff (1865-1937) informed Wilhelm II, German Emperor (1859-1941) and Chancellor George Count von Hertling (1843-1919) that Germany could not win the war. On 18 July, Entente forces launched a counterattack that forced German troops back to the Marne River and compelled General Ludendorff to cancel his planned Flanders offensive drive on 20 July. The Entente had seized the initiative from the Germans for good. A week later, the Entente leadership planned a series of attacks that allowed the Germans no respite. The offensive from 8 August to 4 September targeted Amiens and ultimately reduced the German salient south of the Somme River. The battle is notable for the effective coordination of British-French infantry, artillery, and airplanes. During the first operational day, Allied troops advanced six miles on a twelve-mile front. This was General Ludendorff’s infamous “Black Day” for the German army, as many of his troops surrendered after offering little more than token resistance to the attackers. Entente pressure prevented the Germans from launching a counteroffensive. The army had begun to disintegrate as up to 1,500,000 soldiers were reported missing or had deserted.

As the military situation worsened, despair spread throughout the Central Powers’ ranks. At a 13 August meeting at Spa, General Arthur Arz von Straußenburg (1857-1935) informed the German High Command that his army could not continue to fight past December. Then the news arrived that the British government had officially recognized the Czech-Slovak National Council in Paris.

Meanwhile, by 9 September on the Western Front, the British and French had recaptured all the territory the Germans had conquered during their 1918 spring offensives and showed few signs of slowing down. By late summer 1918, German armed forces neared complete exhaustion on the Western Front, as the Entente blockade increased the civilian starvation levels and war-weariness accelerated in both Germany and Austria-Hungary. Already on 2 September, the first German Hindenburg Line defensive positions had been breached.[3] The German High Command had wanted the maintenance of those formidable defensive positions to be a bargaining tool in future peace negotiations.

The German Home Front↑

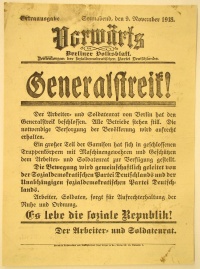

On the German home front, draconian rationing of the dwindling food supplies and grave shortages of raw materials led to strikes, demonstrations, and civil unrest. During early 1918, massive strikes, far larger than previous stoppages, broke out all over Germany. Hundreds of thousands of people protested the steadily worsening food situation. In the process, the USPD Party (Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany) split from the Socialist Party and demanded immediate peace without annexations. The Socialist Party trade unions did not encourage the strike movement, striving instead to maintain the early war unity (Burgfrieden).[4]

Despite their efforts, the social and political order began to disintegrate after a major ammunition-workers strike erupted in January and the tightening Entente blockade further restricted the food supply. The Hohenzollern ruler, Emperor Wilhelm II, became a major symbol of discontent among evolving revolutionary groups. Wilhelm’s demonstrated weakness as a wartime ruler resulted in accelerating disrespect for his authority and the very institution of the emperorship. Meanwhile, the Hindenburg “myth” endured through the 1918 German offensive, as the people still trusted him.[5] A further cut in rations produced additional strikes in Berlin and Leipzig, which spread throughout Germany during the summer months. The increasing lack of food weakened efforts to maintain industrial production.

Thus, during 1918, revolutions erupted in both Austria-Hungary and Germany following military defeat after four years of warfare. This final defeat produced the conditions and the impetus for revolutionary activity and demonstrations. These upheavals, however, proved less destructive and far less radical than the 1917 Russian Revolutions.

The same war-weariness that had long gripped Austria-Hungary and Bulgaria finally took its toll on the German population. Basic commodities, and especially fuel, became scarcer by the day and the inflation rate had already increased four times since 1914. Many German civilians scoured both street and countryside in search of food, often resorting to raiding garbage cans for rotting meats and vegetables. The social, political, and economic structure of the Central Powers began to disintegrate as strikes and unrest spread with the increasing war-weariness.

German agricultural output plummeted due to enduring manpower shortages, lack of fertilizer, and poor weather conditions. The social strain of attempting to mobilize resources for total war (the infamous “Hindenburg Program”) increased due to the 1918 spring offensive failures. In addition to sacrificing many of the best storm troopers, the offensives exhausted the German army and destroyed national morale.[6] Troop cohesion and unit resilience deteriorated following the devastating Entente counteroffensive. The obvious expanding Entente superiority in both manpower and material and its overwhelming supremacy both on land and in the air further depressed the remaining troops, many of whom surrendered to the enemy as Germany was forced to revert to the defensive. The army now suffered a serious loss of manpower, lacked ammunition and artillery shells, and no longer possessed reserve formations. A quarter million casualties had been sustained after the second retreat from the Marne River, and tens of thousands of troops deserted when Entente forces attacked the Hindenburg Line.

Allied Fall Campaign↑

The decisive 26 September Meuse-Argonne Offensive against the German Hindenburg Line continued during the successful Hundred Days Offensive until the end of the war. German troops were now truly exhausted. Entente offensives continued unabated after 28 September, as the German government learned that Generals Hindenburg and Ludendorff were demanding peace negotiations. Meanwhile, the entire Bulgarian front crumbled after an Allied Salonika Army offensive launched from Greece severed communication between Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Turkey. On 15 September, the international Entente force defeated the starving, demoralized Bulgarian Army at the Battle of Dobro Pole. After the Bulgarians signed an unconditional surrender with the Salonika group commanders on 30 September, the Central Power Balkan front defense dissolved, leaving the Balkan Peninsula open to an Entente offensive. Troops could not be transported from other fronts and deployed rapidly enough to halt the Entente advances (the reinforcements would have come from the Serbian and Ukrainian fronts). Turkey also signed an armistice agreement shortly thereafter on 30 October. This represented the beginning of the end militarily for Austria-Hungary and Germany. The Bulgarian collapse created significant danger for both the Habsburg Balkan front and for Turkey. The Turks had fought for three years before the outbreak of the First World War. First, they fought in Italy in the Italo-Turkish War and then against various Balkan states, which initiated the two Balkan wars in 1912-1913. Following those conflicts, the German General Staff considered the Turkish army powerless.

However, with the July 1914 crisis and outbreak of war, the Young Turks leadership determined that they should ally with Germany, the strongest military power in Europe. Negotiations occurred on 2 August, but it was not until November that the Turks actively entered the war. From December 1914 to January 1915 the Turks initiated a campaign in the Caucasus Mountains that resulted in disaster for them. In addition, they failed in their attempt to cross the Sinai Desert to seize the Suez Canal.

The following year the Turks made a second attempt to seize the Suez Canal, but once again were repulsed. To continue fighting, the Turks desperately needed military equipment and ammunition. In the fall of 1915, following the Central Powers’ successful Gorlice-Tarnów Offensive and the invasion and defeat of Serbia, supply routes opened allowing for the transportation of equipment to the Turks. Throughout 1916, warfare in the Middle East intensified. The Turks, however, continued their Caucasus campaign and even provided four infantry divisions for the Eastern Front during the Brusilov Offensive. The Palestinian campaign in 1917 was catastrophic and they were forced to surrender the Middle East to the British and French. The Turks ended their participation in the war in October 1918, immediately after the Bulgarian collapse, by signing an armistice.

New German Government↑

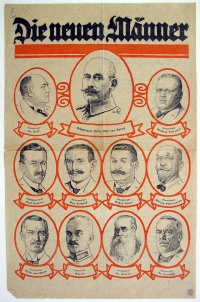

After the failure of the spring offensives, the disastrous defeat in the Balkan theater, and the collapse of the German Western Front, General Ludendorff suddenly proclaimed on 3 October that the war was lost and that the German government must immediately seek an acceptable armistice and peace from the Allies. This stunning admission negatively affected the morale of those who had been strong supporters of the war. By accepting defeat, the German government also realized that it had to initiate meaningful constitutional changes, which resulted in the formation of a new government on 3 October headed by Prince Max von Baden (1867-1929) and supported by a parliamentary majority consisting of the Center, Progressive, and Social Democratic parties. By proclamation, the new government became responsible to the Reichstag for military and foreign policy. This provided the impetus to establish a constitutional monarchy with a responsible government, which, unfortunately, ended in failure.

On 3 October, Prince Max von Baden became Chancellor of the new liberal German government. On 4 October he dispatched a formal note requesting an armistice based on President Wilson’s Fourteen Points. This move came under increasing domestic pressure, as well as the realization that, in a speech made to Congress, President Wilson had made a distinction between the German people and the Hohenzollern dynasty. Wilson would not negotiate with the autocratic leader. This paved the way for negotiations based on initiating change in German political leadership. General Ludendorff, who would tender his resignation to the civilian government by the end of the month, utilized these requests for an armistice as a means to discredit left-wing political forces and deflect blame for Germany’s military defeat from its General Staff. This would later serve as “evidence” for the infamous German “stab-in-the-back” thesis (Dolchstoβlegende), which Adolf Hitler (1889-1945) recited tirelessly during his rise to power in the 1930s, claiming that the army had been defeated not on the battlefield, but by the Socialists, Jews, and liberal politicians at home.

The German High Command’s demand for an immediate armistice on 3 October came as a complete shock to most of the country. The astonished Berlin political leaders and Reichstag had been informed of the deteriorating military situation only the day before. Four years of battlefield victories and continued newspaper coverage of the vast enemy territory that had been conquered had suddenly somehow resulted in military defeat – literally overnight. Astounded, people asked how this could have happened, considering that their armies occupied much of Russia’s territory and possessed a number of satellite states including the Baltic States, Ukraine, Poland, Romania, and Belgium. Panic gripped the German people as they realized that the war was lost.[7]

The resultant note from the Central Powers to President Wilson on 4 October requesting an armistice based on his Fourteen Points led to a round of negotiations and prompted a public exchange of notes from 4 to 23 October between President Wilson, Austria-Hungary, and Germany. President Wilson transmitted messages to the Central Powers on 8, 14, and 23 October. He transmitted his first note on 8 October without first consulting his Entente allies. Wilson wanted confirmation that his Fourteen Points formed the basis for further discussions. Meanwhile, the Germans responded to Wilson’s notes on 12, 20, and 27 October. The negotiations coincided with the transfer of military power from the German General Staff to the civilian leaders of the newly announced government.

By the end of October the German people wanted the war to end. In the negotiations for peace, Max von Baden ignored Emperor Wilhelm. By 28 October the German constitution had been revised in the first significant changes to the early Bismarck Constitution since 1871. The Emperor no longer held any of his former major powers. The German Chancellor now was responsible to the Reichstag, and foreign and military affairs reverted to civilian control. Wilhelm departed his homeland on 29 October, ending over 500 years of Hohenzollern rule.

The Austro-Hungarian Front↑

The Habsburg Army launched an offensive on the Italian front on 15 June. The operation was delayed by inclement weather and the rugged mountain terrain. The overtaxed railroads could not meet the demand of transporting troops, food, and equipment. On the eve of the 15 June offensive, the army’s food supplies could only last a few days. Habsburg Army troop numbers had meanwhile dropped precipitously, while three separate command groups were separated by hundreds of kilometers, posing an insurmountable challenge for the operation. Charles I, Emperor of Austria (1887-1922) divided Habsburg forces between the Isonzo and Tyrolean fronts. In the meantime, the Italian army had been replenished with eleven British and French divisions, as well as resupplied with artillery and other weapons from the October 1917 Caporetto battlefield debacle.[8]

Initial Habsburg gains, coming on the heels of some early successes on the Piave front, were quickly negated by Italian counterattacks. The Italians had learned the attack plans from Habsburg deserters, and air reconnaissance located pertinent troop assembly areas. Constant rainfall caused the Piave River to spill over its banks, washing away the attackers’ pontoon bridges and cutting off Habsburg escape routes. The failed campaign led to the loss of 143,000 troops. Thus, the civilian population that believed the offensive would result in another 1917 Caporetto-style victory was stunned by the overwhelming defeat.

Following the disastrous Habsburg offensive, the Italian front fell quiet as attention shifted to the Western Front, where the war would presumably be decided. During the first week of July, the Italians launched a counterattack, turning the tide on that front. Disease began to take an increasing toll on Habsburg soldiers on the Piave River front area. The Austro-Hungarian soldiers’ morale sank as disease, particularly malaria, spread through the ranks, claiming two to three times as many men as were lost to the enemy. The soldiers literally became skeletons from lack of proper nourishment. Between 1 July and the end of September, Habsburg troop numbers dipped from 650,000 to 400,000, mostly from desertions, although malaria, dysentery, malnutrition, and the Spanish flu also took their toll. The July and August 1918 famine negatively affected civilian and military consumption and morale. By August, Habsburg troops on the Italian front were digging up graves to remove military uniforms from their buried comrades, as most remaining soldiers lacked basic clothing. The Habsburg Sixth Army reported that the average infantryman’s weight had decreased to 120 pounds. Through mid-August, on the Isonzo River troops suffered 600 to 800 cases of malaria daily. Many troops, now basically skeletons, suffered from various ailments, becoming pathetic shadows of their former selves.[9] The toll became obvious in September as troop numbers dwindled.[10] Negative news about conditions back home also began to prey on soldiers’ psyches. The intensifying war-weariness, food crisis, and fuel shortage on the home front brought economic and nationalistic issues together explosively.

On the German front, retreat movements shortened the front lines, while fear of revolution and Bolshevik activity grew in the hinterlands of the Central Powers. The Allies agreed that a peace settlement was necessary. Habsburg Supreme Command attempted to protect the army from the nationalistic revolutionary activities and propaganda. Meanwhile, misery and despair continued on the home front as deserters filled the ranks of “green cadres” that terrorized the countryside behind the front lines.[11]

Early October 1918↑

The Habsburg Army’s collapse accelerated during the first half of October 1918. Mutinies and severe discipline problems resulted from the prolonged political, social, and military events. War-weariness abounded. Entente propaganda proved particularly effective among the various Dual Monarchy nationalities. The citizenry had long since lost respect for its government because of its notoriously lackluster performance and divided Austrian and Hungarian political structures. The return of some 665,000 prisoners-of-war from Russia added Bolshevik propaganda to their anger and defiance. Attempts to send returning soldiers to debriefing camps, Ersatz units, or back to the front resulted in mutinies and widespread desertion. The prolonged conflict and the government’s abject failure to address economic problems further fanned the flames of discontent and revolt. Strikes and unrest plagued both Germany and Austria-Hungary.

Question of an Armistice↑

The disastrous collapse of the Bulgarian front in September caused Austria-Hungary to join Germany’s appeal to President Wilson for an armistice, a desperate attempt at self-preservation by both the emperor and the central government. German Emperor Wilhelm appealed to President Wilson on 16 September for an armistice based on the Fourteen Points, but Wilson had replied that the ruling elites, including the emperor himself, must be replaced before any negotiations could occur. Ultimately, the Central Power troops evacuated conquered Russian territory and restored Serbia, Montenegro, and Romania as a result of their 1918 military defeat and attempts to achieve a viable peace. Viennese leadership also announced that it would accept the demanded Italian frontiers as long as they were based on ethnic boundaries. They even offered to establish a free Poland created from Austro-Prussian territory.[12]

By 20 September, Bulgarian troops had retreated on all fronts. The government requested an armistice on 26 September, which became official on 30 September. This placed Central Power troops in a very precarious military situation on the entire Balkan front. A new defensive line was established on the Danube-Save River line, with Hungary now facing the threat of invasion. The Serbian front collapsed on 20 September, leading Hungarian, Polish, and Czech units to mutiny on the Galician front.

As Habsburg Supreme Command Headquarters prepared for the anticipated Italian offensive, it received word of the armistice negotiations with President Wilson. The armistice question produced increasing paralysis in the ranks as weary soldiers asked why they should put their lives in jeopardy when the end of the war appeared imminent. Meanwhile, the Supreme Command of the Habsburg Army concentrated its efforts on keeping the army intact regardless of battlefield events.

With Hungary also suffering severe domestic turmoil, Budapest announced it had terminated its alliance with Germany and proclaimed Hungary a separate state, ending the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867. This opened a “Pandora’s box” of long-simmering nationalist fervor and revolutionary activity. The Austro-Hungarian central government became paralyzed as the crisis escalated.

On 8 October, President Wilson responded to Prince Max von Baden’s armistice overtures. On the following day, the South Slavs (Slovenes, Serbs and Croatians) and Czechs met at Agram (Zagreb) and Prague, whereupon they determined to establish quasi-national governments. In the meantime, the ethnic cohesion of the Habsburg Army began to collapse, ultimately leading to the implosion of the Empire itself.[13] General Arz meanwhile ordered the creation of an armistice commission in Trent.[14]

Then, on 7 October, the Galician Poles declared their independence from the Habsburg Empire. The following day, a proposal to request an armistice was read before the Austrian parliament (Reichsrat). An official U.S. announcement, however, proclaimed that no answer to the Habsburg peace proposals would be forthcoming at the present time, causing dismay in official Habsburg ruling circles. Germany received a reply in which President Wilson demanded the evacuation of all Entente territory preceding the conclusion of an armistice, while again insisting upon the removal of all traditional Central Power ruling elites, specifically Emperor Wilhelm.

President Wilson’s 8 October diplomatic note contained a list of conditions stipulating that Austria-Hungary must evacuate all Allied territory. Only then would he transmit a separate diplomatic communiqué to Vienna. Whatever the armistice terms might evolve, the Entente Powers intended to make it impossible for Germany to renew armed hostilities. Meanwhile, the situation on the German front became highly unstable and unfavorable, thus leading Germany to ultimately accept Wilson’s Fourteen Points.

On 14 October, Italian, British, and French troops prepared to launch their long-awaited offensive against the Austro-Hungarian army to end the war. The Entente’s military success on the Western Front and the collapse of the Bulgarian front drove the war towards its conclusion. The Italians launched their offensive primarily to ensure territorial gains at the peace conference. The attack was launched on a twenty-two kilometer front supported by 7,700 artillery pieces and fifty-seven infantry divisions. On the same day, the Habsburgs decided to seek an armistice and retreat to their original frontiers.

Internal Problems: Nationalities↑

In the fall of 1918 a general strike erupted throughout Bohemia as the fledgling Czech government began to assemble. In addition, President Wilson’s sharp, second note of 14 October opened the door for decisive negotiations. Any illusions the German government might have harbored about armistice conditions ended with Wilson’s reply. The U.S. President demanded that the German government be replaced by a constitutional body and that German unrestricted submarine warfare be terminated immediately. Simultaneously, Prince Max von Baden received disturbing reports that revealed the extent of the unrest and troop demoralization escalating on the German front. The home front remained in turmoil.[15]

Then, on 15 October, the Habsburg Supreme Command ordered the evacuation of all troops stationed in Russia and Ukraine. This terminated shipments of vital grain supplies to the starving Habsburg population. During the next two weeks, the army began to rapidly disintegrate. The military’s deterioration coincided with the spread of increasingly strident nationalist movements demanding independence, accelerating political collapse.

Emperor Charles’ disastrous “Manifesto,” announced on 16 October, promised to accept autonomous Romanian and Ruthenian National Councils and proclaimed that the Austrian half of the monarchy would become a federal state and introduce reforms. However, instead of accepting the Manifesto, Czech, Slovenian, Polish, and South Slav leaders scrambled to create their own nationalist governments, accelerating internal dissolution. The nationalities believed that the Manifesto signified immediate independence as battlefield defeat loomed. The Czechoslovakian National Council proclaimed a Czech-Slovak provisional government. The Czechoslovakian and South Slav National Councils refused to negotiate with either central government before a peace conference convened. War-weariness had reached a boiling point and conflict intensified as they realized that the war had been lost.

The newly created national governments demanded that all foreign troops be withdrawn from their territories and their national regiments be returned to their new homeland. Czech civil service employees immediately cooperated with their National Council, ignoring Viennese officials. The continued service of Habsburg bureaucratic figures and administrators enabled the successor states to establish solid foundations for their new governments.

Rail transport of Habsburg troops was also halted in those territories. In particular, a Czech blockade of food supplies proved a formidable political weapon against the half-starved population of Vienna. The Hungarians’ unrealistic hope of maintaining their present territorial boundaries collapsed when Romanians and Slovaks announced their intentions to secede from Hungary. Some Romanian leaders ordered the integration of the Bukovina into Romania. Romanian soldiers eventually marched into the province, occupying parts of it on 11 November. Meanwhile, General Arz, Chief of the Austro-Hungarian General Staff, suppressed the announcement of the Emperor’s Manifesto for several days, fearing its negative effects on the front line troops and the confusion it would create in the officer corps.

Emperor Charles’ actions and continued South Slav problems created an increasingly chaotic situation on the domestic front. Initially, only rumors of the revolutionary events on the home front reached the front line troops, but they negatively affected troop morale nevertheless. Then, the former kaisertreu Hungarian Premier István Tisza (1861-1918) gave his infamous “the war is lost” speech in Budapest after Emperor Charles’ manifesto had been announced. This had a major effect on Honvéd troops,[16] causing immediate agitation in their ranks.

In response to President Wilson’s note to the German government, General Arz ordered the evacuation of Habsburg troops from the Venetian Plain by 17 October. Simultaneously, armistice committees were created for the Habsburg Italian front.[17] In Germany, the war cabinet decided to accept President Wilson’s armistice terms. On 20-21 October, the German government formally appealed to President Wilson for an armistice and agreed to evacuate all occupied territories and to revise its constitution according to more democratic principles.

President Wilson’s rejection of the Habsburg armistice request and Emperor Charles’ promise of “autonomy” for his Czech-Slovak and Southern Slav peoples provided the death sentence for the Dual Monarchy. Several key national groups demanded their complete independence as central Habsburg administrative orders and decrees went ignored. The Habsburg Supreme Command attempted to meet with representatives of the various nationalities as they began to plan their future status outside of the Dual Monarchy, but these groups had no desire to assist Habsburg military authorities in continuing the war. President Wilson’s emphasis on self-determination for the various national groups comprising the Dual Monarchy made any mediation with the Habsburg authorities irrelevant. Although senior army commanders made plans to intervene in the Dual Monarchy’s internal crisis when the war ended, Emperor Charles wisely resisted pressure to deploy Habsburg troops against the newly emerging states.

The turning point in the war came on 20 October as growing discontent produced unrest throughout the Dual Monarchy. The Hungarian Parliament voted on constitutional changes and severed formal ties with Austria, the only remaining connection being Emperor Charles. Thus Hungary had declared its independence. The same day, Habsburg Supreme Command dispatched General Staff officers to Prague, Kraków, Laibach, and Agram to enlist the national assemblies against the outbreak of anarchy among the troops, which it feared might spread to other parts of the Empire, particularly German Austria.[18] Supreme Command claimed that armed hordes could pillage and plunder as they returned to their homes. The appeals went unanswered as nationalist politicians heralded the approach of the Habsburg collapse. Various national soldiers began to return home, while during the following two days portions of several front line divisions mutinied or refused to obey orders.

President Wilson Changes Position↑

Then, on 21 October, President Wilson announced that he had altered his earlier 8 January stance because of events that had transpired since then. He recognized Czechoslovakia as a belligerent nation and its National Council as its formal government. He also demanded justice for the South Slav nationalist aspirations. The Wilson note removed any questions about his stance. Germany must be made incapable of renewing hostilities, and he would only negotiate with a representative government. On that same day, twenty-one of the fifty-seven Habsburg infantry divisions on the Italian front refused to obey orders, spurring the collapse of the Habsburg Army. On the home front, new demonstrations erupted in Prague and Kraków, while the revolutionary Hungarian Parliament, led by Count Mihaly Karolyi (1875-1955), recalled all Honvéd regiments from the various fronts in reaction to the negative Balkan military situation.[19]

By 23 October, the peace offering and changes in the German government had greatly affected public opinion and further radicalized the masses. The increasing chaos, combined with Allied demands for total capitulation and the floundering attempts to force Emperor Wilhelm to abdicate in favor of his grandson, severely undermined Max von Baden’s political position.

The Collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Army↑

The collapse of the Habsburg Army accelerated on 22 October as multiple regiments began to mutiny, demonstrations erupted in Prague and Kraków, and a National Commission of Polish representatives convened in Kraków. On 23 October, President Wilson’s third note to Germany made it abundantly clear that the U.S. would not negotiate with the monarchial German government, only with representatives of the people. Meanwhile, as increasingly negative news arrived from the Balkan front Habsburg Emperor Charles traveled to Hungary to be crowned King of Hungary. During this period, attempts to isolate front line soldiers from the turmoil in the interior failed.

The long anticipated and dreaded turmoil had already erupted in the Budapest Parliament, the heart of the Magyar revolution. Violent action forced the Parliament to be suspended. The turmoil forced Prime Minister Alexander Wekerle (1848-1921) to resign. On 23 October, Hungarian political leaders in the new revolutionary government ordered its troops to be immediately redeployed home to protect the homeland from the anticipated invasion from the Serbian front and possibly the Romanian front.

On that same day, a provisional government proclaimed an independent Czech-Slovak state in Paris, while a newly created Polish state came into existence. Croatia, Slovenia, and Dalmatia rapidly seceded from the Empire. Meanwhile, the Habsburg home front also collapsed. Its army’s final mountain battle would soon commence on the Italian Front. General Arz informed German High Command that his forces could only continue to fight until the end of that year.

The domestic crisis also intensified in the Austro-Hungarian and German homelands. Habsburg Supreme Command continued to fear the outbreak of anarchy when troops returned home. Meanwhile, the government became paralyzed as anti-dynastic agitation increased everywhere. The Croats rebelled in Fiume, while Croats, Bosnians, Czechs, Magyars, and Romanians deserted their posts in Venetia. The Habsburg Army entered a state of open revolt and informal dissolution.[20] As the Dual Monarchy fragmented, German politicians of all parties in the provisional Austrian National Assembly proclaimed a new Austrian state to embrace the German-speaking areas of the former Empire, including the predominately German-speaking districts of Bohemia. The provisional assembly managed public affairs until a constitution for the truncated Austria was drafted. Emperor Charles’ last government was formed under the college professor Heinrich Lammasch (1853-1920). In a note dispatched to President Wilson, Lammasch agreed to the president’s concept of the right of nationalities to develop their own future within the Dual Monarchy, particularly the Czechs and South Slavs.[21]

The effect of propaganda on Habsburg troops accelerated the spread of the rebellion as soldiers of all nationalities developed the overwhelming desire to return home. Emperor Charles agreed that Hungarian soldiers could return to defend their homeland from invasion. The decision enflamed Czech-Slovak and South Slav opposition to the Dual Monarchy, a key factor that, along with general war-weariness and the increasingly unstable situation on the home fronts, led to the dissolution of the army. Escalating economic and political unrest at home also had a devastating effect on the army. Some front line Hungarian units rebelled and started home.

By 23 October, all Habsburg Supreme Command attempts to isolate news of the increasing number of disturbances in the hinterlands from front line combatants had collapsed. South Slav and Hungarian troops began to refuse to continue fighting as serious rebellions, desertion, and mutiny occurred.[22]

Final Italian Offensive↑

The Italians finally launched their long anticipated offensive against the beleaguered Habsburg Army on 24 October.[23] Although the operation caught the Habsburg Supreme Command by surprise, the defending troops fought fiercely, driven by the instinct to survive. Losses for both sides proved significant, while the Hungarian government repeated the demand that their soldiers return to protect their homeland. Habsburg troops could not halt the Italian attacks with such high casualty rates and intensifying disturbances in the ranks.

At this point, the army had become catastrophically low on all supplies of food, ammunition, and troops, who were by now completely demoralized. Equipment, particularly artillery pieces, continued to fail at an alarming rate. Troop morale also collapsed and the troops became unreliable in battle. Reserve units refused to advance to the front, while more and more unit formations mutinied. General Arz revealed to the German High Command that half of his soldiers had revolted. Troops of every nationality increasingly abandoned their front line positions. Discipline also collapsed in the rear echelons, where newspaper articles from the home front negatively affected the troops. By 25 October, in an effort to protect the army from total collapse, Habsburg Supreme Command demanded an immediate ceasefire (Waffenstillstand) as serious battle continued. Severe losses continued to reduce troop numbers as soldiers slowly surrendered territory.[24] Ammunition supplies had also dwindled to one-day’s worth as mutinies spread.

The major blow from the Italian military did not occur until 26 October. Habsburg reserve formations and reinforcement troops refused orders to advance to the front lines to prevent a major battlefield defeat. To add to the disastrous situation, many Habsburg front-line artillery pieces had become unserviceable, while other batteries lacked horses to transport them.

The Italians increased pressure on their opponent’s collapsing fronts. Habsburg March formations (replacement troops) often proved unreliable and undisciplined. The military situation had deteriorated so badly that a Habsburg Supreme Command delegation traveled to the front lines to attempt to persuade the troops to defend their positions until an armistice could be concluded. En masse mutinies and desertions became the order of the day. Continued artillery fire camouflaged the fact that portions of the Habsburg front had disintegrated. Thus, the Italian High Command did not realize the accelerating chaos occurring behind Habsburg lines.

During the early morning hours of 27 October, several Italian Army units crossed the Piave River. No Habsburg counterattacks or serious resistance could be achieved because so many troops refused to fight. Many soldiers also deserted their units. On 26-27 October, at least thirteen Habsburg divisions were in dissolution. Most Hungarian troops refused to obey orders.[25] By 28 October, troops of all nationalities were marching homeward. The Habsburg military situation continued to deteriorate rapidly into hopelessness. Multiple divisions refused to defend their front lines and instead marched to rear echelon areas, which only accelerated the army’s disintegration.

Question of an Armistice↑

Insubordination in training camps had been a problem since the early weeks of October, when many recruits had refused to join their regiments at the front lines. Mutinies coincided with disturbances and demonstrations at various areas of the front to further cripple Habsburg military efforts. Meanwhile, many divisions simply refused to fight. Troops deserted their trench positions, some attempting to march home. March formations continued to disobey orders to proceed to the front, and almost all remaining Hungarian troops demanded that they be allowed to return to their homeland because of the increasingly dangerous military situation on the Balkan front. Habsburg officers became powerless to command their troops. In the meantime, the Habsburg Supreme Command vehemently insisted that an armistice be concluded as rapidly as possible before “anarchy and Bolshevism” could poison both the army and the home front, particularly in the German areas of the Dual Monarchy.

The Habsburg Army’s ultimate fate was determined on 28 October as the Dual Monarchy received a final shattering blow when the government acknowledged the Czechs’ and South Slavs’ independence. The decision did not put an end to the fighting and did little to alleviate the pressure on the faltering Habsburg Army.

The troop rebellions following on the heels of President Wilson’s third note on 28 October finally caused the German politicians to react. At the same time, General Arz telegraphed General Hindenburg demanding an immediate armistice regardless of the present German position.

The commander of the Isonzo front reported that organized resistance on his front was no longer possible. Thus, several attempts followed to secure a cease-fire that would preclude the total collapse of the front as mutiny spread to all units. Several more divisions refused to fight and reserve units refused to march to the front. Insubordinate soldiers even began to plunder supply depots, a further indication of the seriousness of the situation.[26]

Meanwhile, a planned 28 October Habsburg counterattack had to be scrubbed because three infantry divisions in the assault force had mutinied. Some units had reached the verge of dissolution; none existed to fill the accelerating number of gaps in the front lines. All communication between the various units had vanished. Emperor Charles and General Arz sought an immediate end to hostilities and “the completely useless bloodletting on the front.” Both were willing to accept any armistice terms as long as the honor of the Habsburg Army remained intact.[27]

The Habsburg Supreme Command continued to attempt to prevent the disintegration of the army. The fear of anarchy increased demands for an armistice. Haunted by the fear of a Bolshevik upheaval in the ranks, General Arz authorized direct consultations with the Italians for an immediate armistice. The inevitable Habsburg general retreat commenced on 29 October.

General Svetozar Boroević von Bojna (1856-1920) sought to prevent anarchy in the ranks as he ordered a retreat to the front lines the Habsburg Army had occupied before the 1917 Caporetto campaign. Meanwhile, General Arz informed General Hindenburg that the Habsburg Monarchy must demand an immediate armistice. General Arz ordered present front line positions be maintained as long as possible in order to prevent the destruction of the army until an armistice could be concluded. The fate of the Habsburg Army had been sealed.

Habsburg Army commanders insisted that unless an armistice was signed immediately, the situation would become catastrophic. Officers attempted to maintain control of their few remaining obedient troops, but had to halt all combat operations and attempt to neutralize the influence of rebellious soldiers. The troops, nevertheless, continued the general retreat as the army disintegrated. A definitive front line no longer existed as unit entities turned into masses of soldiers often retreating. German military leadership was seriously concerned that the Entente would send troops through the Tyrol to invade Bavaria.

Revolt of the Nationalities↑

Nationalist movements increasingly undermined the Habsburg war effort. On 31 October, politicians in Prague proclaimed a Czech state joined by Slovakia.[28] Galician leaders announced that they would join a new Polish state. After the Czechoslovakian political revolution, Habsburg military garrisons had to be withdrawn from Czechoslovak territory. In Agram military authorities transferred their command to the South Slav National Council. People in Croatia demanded their independence from Hungary as street demonstrations erupted. The Slovak National Party and Slovenes sought a timely break from Hungary, but the Slovak National Council meeting on 30 October favored unification with the Czechs. Returning Czech soldiers were greeted as heroes at home.

The alliance with Germany proved fatal to Vienna. Because of the earlier Sixtus Affair, at the Spa meeting in May the Entente powers regarded the Dual Monarchy as an appendage of Germany.[29] The floodgates opened as the Western powers sought to break up the tottering Habsburg kingdoms.

Although Germany was spared the turmoil of nationalist revolutions, it suffered from the same war-weariness and domestic political unrest. More and more troops refused to obey orders even before a deadly wave of the Spanish flu struck one of every six men in late October. The High Seas Fleet mutinied on 29 October after receiving orders to launch a suicide mission to attack the British Grand Fleet. Sailors demonstrated for peace and called for an end to the war, even going so far as to create counsels on the Bolshevik model to facilitate further political revolution. The movement spread throughout German seaports as sailors and workers seized entire ships. Their actions received support from the growing anti-war fever, which had become more pronounced after news from the Bulgarian-Turkish fronts reached the homeland.[30] Hoping to hasten the armistice negotiations and avoid a major revolution, German leaders sought to placate President Wilson by making the new chancellor responsible to the Reichstag.

Meanwhile, pandemonium continued in the Dual Monarchy. On 30 October, the Provisional Assembly in Vienna accepted a temporary constitution that formed German Austria into a part of the German Republic. German regions in Bohemia, Moravia, and Silesia also declared the creation of an independent Austrian state. It now became a question of destroying the Habsburg Empire in as orderly a fashion as possible and transfering authority to the heirs of the Habsburg Dual Monarchy. As the Habsburg Supreme Command lost control of troops in the Hinterland, it continued to fear anarchy in the ranks.

Chaos continued in the Empire as German-speaking sectors of Austria and Bohemia declared their independence and a republican form of government.[31] Meanwhile, combat troops continued to desert and mutiny in the Hinterland. Austria-Hungary ceased to exist as new independent states replaced it. In Hungary demonstrations erupted and a group of soldiers murdered István Tisza at his home.[32] The Hungarian revolutionary Karolyi declared that Emperor Charles should abdicate and announced the formation of a Hungarian Republic, abrogating the 1867 Compromise between Austria and Hungary.

Collapse on the Italian Front↑

Even as the Empire was collapsing and dissolving, the armies still firmly controlled their section of the Italian front. However, soldiers ignored their officers and animals were set free. Two forms of contagious infections spread within the Habsburg forces. Influenza decimated ranks of garrison troops guarding various roads, further diminishing the troops’ willingness to fight. Habsburg commanders thought it better to surrender as soon as possible rather than witness the chaos that would occur if hundreds of thousands of armed undisciplined troops arrived back home. Even German Austrian soldiers took part in the spreading revolts.

The pacifist Hungarian War Minister, Béla Linder (1876-1962), ordered his Hungarian soldiers to put down their arms and demanded that all Hungarian soldiers deployed in Ukraine be sent back home without weapons or military materials.[33] Troops would join units according to the new nation they represented. The soldiers, anxious to get home, clogged the roads to proceed to the nearest railroad station where the lack of coal for the locomotives made it difficult to get a ride. The lack of coal resulted from the fact that miners did not have sufficient food to continue their heavy labor. Farmers did not provide food because many former farm workers now served in the armed forces. Neither the home nor battlefronts were receiving regular food shipments, which further impeded all types of activities. Meanwhile, Czechoslovakians and Yugoslavs forbade the movement of troop convoys, resulting in a true paralysis throughout the old Empire as millions of soldiers attempted to reach home. Many troops refused to obey orders and officers were rebuffed. Rearguard troops were preceded by undisciplined armed troops who ransacked buildings looking for food and valuables.[34] Disorder also reigned in the Habsburg Supreme Command headquarters. Telephone switchboards were vandalized and abandoned, cars were stolen, and many officers deserted and headed home.

The End of Germany and the Dual Monarchy↑

By 31 October the Dual Monarchy had all but ceased to function, with several independent states replacing it. By November, almost all Hungarian troops had disappeared from the frontlines. Meanwhile, soldiers rushing home presented a threat to Austria and Hungary, as well as to the successor states, because of the anarchy and revolutionary ideas that they could spread to the hinterland. Yet during the last days of the war, some Austrian-German, Hungarian, Czech, Slovene, and Croat soldiers fought to the bitter end and died on the battlefield side by side, even though the Austro-Hungarian Army no longer existed. The army’s armistice commission finally crossed the Italian front lines on 31 October to conduct negotiations. The Habsburg Commission then learned that the Italian negotiating team would not arrive until the next day, continuing the obvious Italian delaying tactics. The Habsburg delegation arrived in Italian headquarters at the Villa Giusti to await armistice terms, which in reality, amounted to a total capitulation.[35]

The Italians accepted a cease-fire for 3 November, but then attacked Habsburg troops the next day, gaining the reputed great victory of Vittorio Veneto. The German armistice delegation had seventy-two hours to sign the surrender documents on the Western Front. Emperor Wilhelm fled the country on 10 November, and the armistice finally took effect on 11 November at 11:00 a.m. Attention focused on the peace treaty negotiations. While the Austro-Hungarian Army suffered an inglorious death, German troops marched home to open arms after the 11 November termination of the war. Attention now focused on the Versailles peace settlement and its effects.

On 7 November, Max von Baden described the critical situation in Germany while Emperor Wilhelm travelled to Army Headquarters at Spa. Pressure had been mounting for Wilhelm to abdicate, but he suggested that he lead the army to bring peace to the homeland. Senior army commanders quickly vetoed the idea. On the same day, a revolution in Bavaria overthrew the Wittelsbach dynasty and the king fled. Two days later, revolutionary activities expanded in Berlin, particularly encouraged by Karl Liebknecht (1871-1919), a leader of the Spartacist League, the far left-wing of the Socialist Party. Crime escalated, with murder and soldier desertion becoming regular occurrences. Workers had improved their lot, but the middle class had lost their savings.

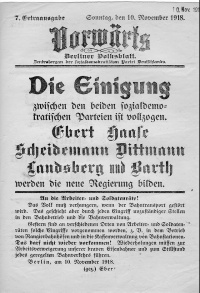

On 9 November, Prince Max (who held office from 4 October to 13 November) declared Emperor Wilhelm’s abdication, because he feared that a continued impasse on the subject would assist the left-wing revolutionary parties and factions, particularly the Spartacists. Wilhelm fled to Holland the next day. Max then retired in favor of Friedrich Ebert (1871-1925), the leader of the majority Socialists. On November 10, the just-elected president contacted the new Germany army commander, Wilhelm Gröner (1867-1939), to secure the military’s support against the Spartacists. With the military supporting him, Ebert then focused on procuring peace and establishing internal order to ensure Germany’s survival. On November 9, the Socialist Philip Scheidemann (1865-1939) appeared on the balcony of the Reichstag and, without any authority, proclaimed a German Republic to prevent the repetition of Red October as had occurred in Petrograd in 1917. Like Max and Ebert, he feared a Spartacist-led communist attempt to seize power. Karl Liebknecht led such an uprising, but failed to provide adequate leadership for it to succeed. He and his fellow conspirators, including Rosa Luxemburg (1871-1919), were murdered.[36]

The elections of 19 January 1919 resulted in the Social Democratic Party emerging as the largest party in the Reichstag. They and the Catholic Center Party combined to form a parliamentary and republican majority. After suffering through the revolutionary events between November 1918 and January 1919 – precipitated by battlefield defeat and the replacement of the Hohenzollern Emperor and imperial government – Germany finally seemed to be on a path to social and political stability. There would be no purges of civil servants, members of the diplomatic corps, the judiciary, or military officers.

Conclusion↑

The events of October 1918 brought a rapid end to Austria-Hungary and Germany’s World War destiny. Four bloody years of conflict, increasing starvation conditions affected by the Entente blockade, and escalating strike activity combined to create the conditions for revolution. The failure of the German spring offensives of 1918 and the collapse of the Habsburg Army following the catastrophic June Battle of the Piave ended any hope for a military victory for the Central Powers.

One must also consider how the appeals by the two main Central Power countries for an armistice affected the post-war order, leading to the enormous influence of President Wilson’s Fourteen Points. The Austro-Hungarian monarchy and its various national sections could not survive the Fourteen Points and the policies, or lack thereof, of Emperor Charles. His ill-advised “Manifesto” is an excellent example of how the emperor’s decisions could have disastrous consequences for his country.

For Germany, the U.S. president emphasized that he would not negotiate for an armistice with Emperor Wilhelm. This not only resulted in the collapse of the Hohenzollern dynasty, but also in the birth of a constitutional republic in Germany. The fateful Versailles Treaty negotiations resulted in the May 1919 draconian settlement after the German delegates took their railroad journey to see the documents for the first time.

Graydon A. Tunstall, University of South Florida

Section Editors: Michael Neiberg; Sophie De Schaepdrijver

Notes

- ↑ Herwig, Holger H.: The First World War. Germany and Austria-Hungary 1914-1918, New York 1997, p. 362; Rauchensteiner, Manfried: Der Erste Weltkrieg und das Ende der Habsburger-Monarchie 1914-1918, Vienna 2013. Both sources are excellent for basic October 1918 information.

- ↑ Herwig, The First World War 1997, pp. 359, 370, 425.

- ↑ The Hindenburg Line was the major defensive position assumed before the major 1917 French Nivelle Offensive.

- ↑ Food ration per individual had fallen to 60 percent of the amount deemed necessary for even light work. The German strike movement during 1915 had numbered about 137, but grew to 560 by 1917.

- ↑ The "myth" commenced after the great German defensive victory at Tannenberg in 1914, while on the Austro-Hungarian front the Habsburg armies suffered major defeats at the two battles of Lemberg.

- ↑ Herwig, The First World War 1997, pp. 260-266.

- ↑ Ibid, p. 426.

- ↑ Von Glais-Horstenau, Edmund: The Collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, New York 1930; Herwig, The First World War 1997, pp. 368, 370, 373; Rauchensteiner, Der Erste Weltkrieg 2013, p. 995ff.

- ↑ Herwig, The First World War 1997, pp. 365, 434; Rauchensteiner, Der Erste Weltkrieg 2013; Von Glais-Horstenau, The Collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire 1930, p. 235.

- ↑ Von Glais-Horstenau / Kiszling, Rudolf (eds.): Österreich Ungarns Letzter Krieg 1914-1918 (ÖULK), Bundesministerium für Landesverteidigung, 7 vols. VII, Vienna, p. 573.

- ↑ Herwig, The First World War 1997, p. 358; ÖULK and varia.

- ↑ Kerchnawe, Hugo: Der Zusammenbruch der österreichische-ungarische Wehrmacht im Herbst 1918, Munich 1921, p. 15.

- ↑ For a very readable account of events, see: May, Arthur: The Passing of the Hapsburg Monarchy 1914-1918, 2 vols., Philadelphia 1966.

- ↑ ÖULK, VII, p. 579; varia.

- ↑ Herwig, The First World War 1997, pp. 373-387, 444.

- ↑ Honvéd was the designation for Hungarian troop units and soldiers.

- ↑ Rauchensteiner, Der Erste Weltkrieg 2013, varia.

- ↑ Von Glais-Horstenau, The Collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, p. 240.

- ↑ Herwig, The First World War 1997, p. 436; varia.

- ↑ Herwig, The First World War 1997, pp. 436-437.

- ↑ Von Glais-Horstenau, The Collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire 1930, pp. 228, 231-232; Rauchensteiner, Der Erste Weltkrieg 2013, p. 1041ff.

- ↑ ÖULK, VII, p. 591, varia.

- ↑ See: Kerchnawe, Der Zusammenbruch 1921, for details on military operations and nationality issues throughout October and November 1918.

- ↑ ÖULK, VII, p. 600, varia.

- ↑ Rauchensteiner, Der Erste Weltkrieg 2013, p. 1042.

- ↑ Rauchensteiner, Der Erste Weltkrieg 2013, p. 1042; See: Kerchanawe, Der Zusammenbruch 1921; Von Glais-Horstenau, The Collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire 1930, for detailed descriptions of troop activities.

- ↑ Ibid; Rauchensteiner, Der Erste Weltkrieg 2013, p. 1043.

- ↑ See: Plaschka, Richard / Mack, Karlheinz (eds.): Die Auflösung des Habsburgerreiches. Zusammenbruch und Neuorientierung im Donauraum, 1918, Vienna 1974.

- ↑ The Sixtus Affair entailed Habsburg Emperor Charles sending a letter to his relative Sixtus, Prince of Bourbon-Parma (1886-1934) seeking peace terms, which caused outrage among the German General Staff.

- ↑ Herwig, The First World War 1997, p. 421; Rauchensteiner, Der Erste Weltkrieg 2013, p. 1042; see also: von Glais-Horstenau, The Collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire 1930.

- ↑ Rauchensteiner, Der Erste Weltkrieg 2013, p. 1045.

- ↑ Herwig, The First World War 1997, p. 437.

- ↑ Rauchensteiner, Der Erste Weltkrieg 2013, p. 1046.

- ↑ Herwig, The First World War 1997, p. 438.

- ↑ For the negotiations, see: Herwig, The First World War 1997, pp. 437-438; Rauchensteiner, Der Erste Weltkrieg 2013, pp. 1043-1047.

- ↑ Herwig, The First World War 1997, p. 446.

Selected Bibliography

- Cornwall, Mark: The last years of Austria-Hungary. Essays in political and military history, 1908-1918, Exeter 1990: University of Exeter Press.

- Galántai, József: Hungary in the First World War, Budapest 1989: Akadémiai Kiadó.

- Glaise von Horstenau, Edmund: Die Katastrophe. Die Zertrümmerung Österreich-Ungarns und das Werden der Nachfolgestaaten, Zurich 1929: Amalthea-Verlag.

- Glaise von Horstenau, Edmund: The collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, London; Toronto; New York 1930: J. M. Dent; E. P. Dutton.

- Jászi, Oszkár: The dissolution of the Habsburg Monarchy, Chicago 1961: University of Chicago Press.

- Kerchnawe, Hugo: Der Zusammenbruch der Österreichisch-Ungarischen Wehrmacht im Herbst 1918, Munich 1921: J. F. Lehmanns Verlag.

- Landwehr-Pragenau, Ottokar: Hunger. Die Erschöpfungsjahre der Mittelmächte 1917/1918, Zurich 1931: Amalthea.

- May, Arthur James: The passing of the Hapsburg Monarchy, 1914-1918, Philadelphia 1966: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Plaschka, Richard Georg: Avantgarde des Widerstands. Modellfälle militärischer Auflehnung im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert, Vienna 2000: Böhlau.

- Plaschka, Richard Georg: Cattaro-Prague. Revolte und Revolution. Kriegsmarine und Heer Österreich-Ungarns im Feuer der Aufstandsbewegung vom 1. Februar und 28. Oktober 1918, Graz 1963: H. Böhlaus Nachf..

- Plaschka, Richard Georg / Haselsteiner, Horst / Suppan, Arnold: Innere Front. Militärassistenz, Widerstand und Umsturz in der Donaumonarchie 1918, volume 1-2, Vienna 1974: Verlag für Geschichte und Politik.

- Plaschka, Richard Georg / Mack, Karlheinz (eds.): Die Auflösung des Habsburgerreiches. Zusammenbruch und Neuorientierung im Donauraum, Munich 1970: R. Oldenbourg.

- Ritter, Gerhard: The sword and the scepter. The problem of militarism in Germany, volume 3, Coral Gables 1972: University of Miami Press.

- Ritter, Gerhard: The sword and the scepter. The problem of militarism in Germany, volume 4, Coral Gables 1973: University of Miami Press.

- Shanafelt, Gary W.: The secret enemy. Austria-Hungary and the German alliance, 1914-1918, Boulder; New York 1985: East European Monographs; Columbia University Press.

- Stephenson, Scott: The final battle. Soldiers of the Western Front and the German revolution of 1918, Cambridge; New York 2009: Cambridge University Press.

- Zeman, Zbynek Anthony Bohuslav: The break-up of the Habsburg Empire, 1914-1918, London; New York 1961: Oxford University Press.