Introduction↑

The modern historiography of the Battles of Ypres remains firmly grounded in the official histories produced by Britain, France and Germany soon after the war. Recent studies have emphasised the multi-national nature of the battles, which at various times involved Australian, Belgian, Canadian, Indian, New Zealand, North African, South African and West African soldiers. The historiography of Third Ypres remains especially controversial. Modern work emphasises the complexity of the battle but stands divided on whether the British Army conducted the offensive in an appropriate fashion.

The First Battle of Ypres 1914↑

Following German defeat at the Battle of the Marne (6-12 September 1914) and the period of stalemate on the River Aisne, both sides sought to restore movement to the war. This resulted in the “Race to the Sea” as Entente and German forces simultaneously sought to turn the northern flank of their opponent.

Ypres became a focal point of the campaign due to its geographic location and importance as a transportation hub. In October, German forces launched a major offensive that aimed to push forward to the Channel ports of Dunkirk and Calais. To achieve these objectives it was necessary to take Ypres. This resulted in the First Battle of Ypres (19 October-22 November 1914). The engagement pitted German Fourth and Sixth Army against French VIII Army, the British Expeditionary Force and the Belgian Army.

The resulting battle was characterised by bitter and confused fighting. The trenches employed by the Entente defenders were crude compared to the complex earthworks that would feature in the later years of the Western Front, providing cover against bullets but little protection against artillery. Nevertheless, the battle revealed the great difficulties of assaulting entrenched defenders. Despite their numerical superiority and greater weight of artillery, the Germans were unable to break through the Entente line. Rapid rifle, machine gun and artillery fire took a heavy toll on advancing German infantry and their attacks were frequently repulsed with heavy losses.

By the end of the fighting the German offensive had been brought to a standstill. Both sides suffered heavy losses. Germany lost approximately 130,000 men compared to Entente losses of around 100,000 soldiers. Casualties amongst the British Expeditionary Force effectively destroyed Britain’s highly trained pre-war army. Nevertheless, Ypres remained in Entente hands and the battle was celebrated as a victory in Britain.

The Second Battle of Ypres 1915↑

French and British troops were left occupying an exposed salient at the end of the First Battle of Ypres. The relative vulnerability of the Entente position meant that this sector of the front was characterised by incessant trench warfare.

In April 1915 German Fourth Army, facing British Second Army, several French divisions and the Belgian Army, planned an attack towards Ypres. This was primarily to serve as a strategic diversion to cover the transfer of German troops to the Eastern Front and so its objectives were strictly limited and did not extend to the capture of the city itself.

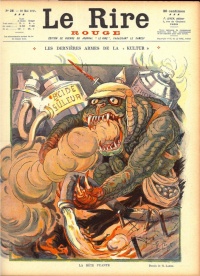

The assault was to be supported by the first large scale use of poison gas on the Western Front. The offensive began on 22 April and the new chemical weapon proved highly effective. Entente troops were taken by surprise and suffered heavy losses due to their lack of protection against poison gas. The scale of success achieved by the initial attack apparently surprised the Germans, who swiftly captured their limited objectives but missed a rare opportunity to press further forward.

In subsequent days the battle degenerated into a see-saw pattern of attack and counterattack. German forces continued to attack, but impetus was gradually lost due to a combination of the diminishing effectiveness of gas, the lack of substantial reserves to exploit breakthroughs, and the tenacious resistance of Entente troops. By the end of the battle German forces had gained around two and a half miles of important ground which further constricted the salient, but Entente forces retained control of Ypres. However, Ypres had been brought into range of German artillery, which reduced the city to rubble. The Germans lost around 35,000 men in the offensive compared to 69,000 Entente troops. The heavy losses amongst Entente soldiers were primarily due to the initial lack of protection against poison gas.

The Third Battle of Ypres 1917↑

In 1917 Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig (1861-1928) decided that the British Army would launch a major attack in the Ypres sector. Circumstances favoured the operation. Britain was suffering at the hands of a renewed U-boat campaign that was operating, in part, from ports on the Belgian coast. A British breakthrough at Ypres would allow an advance to the coast that would eliminate these bases.

Planning for the campaign was hampered by news of the mutiny in the French army, political squabbles, disputes over precise strategy, and Haig’s controversial decision to reject the careful and methodical offensive proposed by General Sir Herbert Plumer (1857-1932) in favour of a more ambitious operation. To this end Haig placed General Sir Hubert Gough (1870-1963) in charge of the attack. Gough’s aggressive approach gained some ground but only at a high cost in British lives. In August, Haig replaced Gough with Plumer, who directed the battle until its close in November.

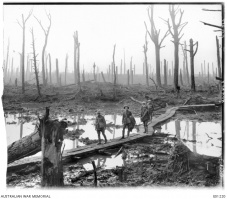

The British offensive, launched by Fifth and Second Army against German Fourth Army, was greatly hampered by abnormally heavy rainfall. Local drainage systems had been destroyed by earlier fighting and as a result the battlefield degenerated into a quagmire. The rain and mud severely hindered the movement of men and materials. In these circumstances a rapid British breakthrough was virtually impossible. Instead, Third Ypres became a remorseless battle of attrition. The Battle of Passchendaele, a bitter and costly engagement fought across devastated, waterlogged terrain on 12 October 1917, is synonymous with the Third Battle of Ypres as a whole.

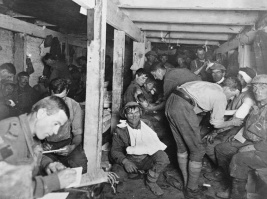

In the Third Battle of Ypres, increasingly advanced British combined arms tactics were pitted against sophisticated German defences based on concrete pillboxes and specialist counterattack formations. Both sides adapted and refined their methods over the course of the engagement. British attacks initially struggled to overcome deep German defences. Advances were broken up by German strongpoints and then driven back by rapid counterattacks. By the mid-stage of the battle, British methods had changed to emphasise a short advance covered by overwhelming artillery support. The newly won position would be consolidated and the incoming German counterattack would be beaten back by massed British firepower. Although not a universal panacea to the problems of trench warfare, this method, commonly known as “bite and hold”, inflicted severe casualties upon German counterattack formations. In response, German forces largely abandoned the occupation of linear trench lines and placed renewed emphasis on elastic defence that occupied shell craters and concrete bunkers.

A combination of dire weather, limited progress and spiralling casualties forced the British to end the offensive in November. The results of the battle remain controversial. Haig’s offensive cost the British Army 244,897 men and failed to eliminate the U-boat threat. Prime Minister David Lloyd George (1863-1945) condemned the operation as a “senseless campaign”.[1] However, although the German line had held, the defenders had suffered at least 217,194 casualties. A German General Staff appreciation of the battle noted that Germany had been brought to the brink of “certain destruction” due to the ruinous losses in Flanders.[2]

Post-War Commemoration↑

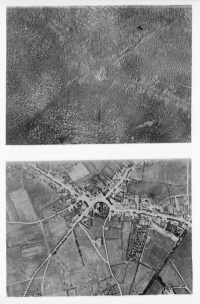

The sheer number of casualties suffered at Ypres made the city a centre for post-war remembrance. The area had significance for British, Commonwealth, German and Belgian commemoration. Ypres was rebuilt to resemble its pre-war state. The narrative of remembrance contrasted the medieval city with the modern, industrial battles that had raged around it. The centrepiece of British and Commonwealth commemoration is the Menin Gate, which lists the names of 54,896 soldiers who have no known grave. The Menin Gate is the site of the unique Last Post Ceremony, a daily event where a small group of buglers sound “The Last Post” and lead the attendees in honouring a minute’s silence for the fallen. On the German side, Käthe Kollwitz’s (1867-1945) famous 1931 sculpture, The Grieving Parents, was inspired by the loss of her youngest son at First Ypres.

Spencer Jones, University of Wolverhampton

Section Editor: Emmanuel Debruyne

Notes

Selected Bibliography

- Der Weltkrieg 1914-1918. Die militärischen Operationen zu Lande. Die Operationen des Jahres 1915. Die Ereignisse im Westen im Frühjahr und Sommer, im Osten vom Frühjahr bis zum Jahresschluss, volume 8, Berlin 1932: Mittler, 1932.

- Der Weltkrieg 1914-1918. Die militärischen Operationen zu Lande. Die Kriegführung in Sommer und Herbst 1917, die Ereignisse außerhalb der Westfront bis November 1918, volume 13, Berlin 1942: Mittler, 1942.

- Der Weltkrieg 1914-1918. Die militärischen Operationen zu Lande. Der Herbst-Feldzug 1914. Im Westen bis zum Stellungskrieg, im Osten bis zum Rückzug, volume 5, Berlin 1929: Mittler, 1929.

- Connelly, Mark L.: The Ypres League and the commemoration of the Ypres salient, 1914-1940, in: War in History 16/1, 2009, pp. 51-76.

- Edmonds, James: Military operations. France and Belgium, 1914. Antwerp, La Bassée, Armentières, Messines and Ypres, October - November 1914, volume 2, London 1925: Macmillan.

- Edmonds, James: Military operations. France and Belgium, 1917. Messines and third Ypres (Passchendaele), volume 2, London 1948: Macmillan.

- Edmonds, James / Wynne, G. C.: Military operations. France and Belgium, 1915. Winter 1914-15. Battle of Neuve Chapelle. Battles of Ypres, volume 1, London 1927: Macmillan.

- Liddle, Peter (ed.): Passchendaele in perspective. The Third Battle of Ypres, London 1997: Leo Cooper.

- Prior, Robin / Wilson, Trevor: Passchendaele. The untold story, New Haven 1996: Yale University Press.

- Sheldon, Jack: The German army at Passchendaele, Barnsley 2007: Pen & Sword.