Introduction↑

The first and second battles of the Marne have much in common. Firstly, these battles were two culminating points of the First World War, which resulted in clear German defeats. Each time, the battlefields were wide areas not necessarily located around the Marne river. The term “Battle of the Marne”, whether it refers to the first or the second, shows Paris’s will to make these events comprehensible and cannot be disconnected from a historical rewriting process that was, in a certain manner, a political tool that aimed to establish France’s leadership in warfare. The two events are clearly different in terms of military and diplomatic plans, not to mention the memory culture around them.

Modern Warfare↑

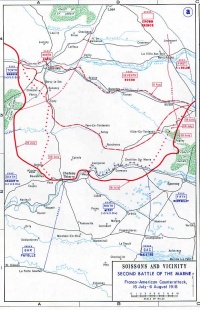

The First Battle of the Marne took place from 6 to 11 September 1914. After having retreated for weeks after the Battle of the Frontiers, the French armies and the British Expeditionary Force counter-attacked on a 300-kilometer-long front. The Second Battle of the Marne took place nearly four years later, from 18 July to the middle of August 1918; from the allied point of view, a very critical moment in the war. After years of trench warfare, German forces had broken through allied defenses and regained an open battlefield, forcing allied troops to a harsh retreat. While the French government had moved to Bordeaux in 1914, Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau (1841-1929) had chosen to remain in the capital. In both battles, German regiments were very close to Paris, with some located only around seventy kilometers away, but they failed to win the final victory.

It has often been said that German losses in both the first and second battles of the Marne resulted from their advance into French territory. It is true that both events underlined some of the permanent difficulties of open warfare, especially from a logistical point of view. Exhausted by weeks of marches, Germans troops suffered from lack of supplies, especially of food, ammunition and, in 1918, fuel.

However, it would be imprecise to state that only the Second Battle of the Marne illustrates the quality of modern warfare. Of course, in 1918, all the armies on the battlefield were much more mechanical than in 1914. Tanks, machine guns, gas, heavy artillery and air power ruled the battleground. In fact, the firepower of a 1918 infantry platoon was far more significant than it had been in 1914. But the First Battle of the Marne also revealed a true learning curve in the French army. The 47th infantry regiment, for example, no longer fought in September 1914 as it had done two weeks before, during the Battle of Charleroi, charging like Napoleonian grognards. Poilus not only dug trenches but used them too, which, of course, made a huge difference.

Transnational Conduct of War↑

On 5 September 1914, General Joseph Joffre (1852-1931) had to convince Marshall John French (1852-1925) to take part in the counter-attack that would later be known as the First Battle of the Marne. Four years later, General Ferdinand Foch (1851-1929) was the supreme commander of the allied armies, coordinating operations on the Western Front since the Doullens Conference of 26 March 1918. The Second Battle of the Marne not only illustrates transnational conduct of war – even if the decision to create a coalition had been taken by the allies only under extreme pressure –, it was also the outcome of the conflict being global, not only European, as in 1914.

After Russia left the battlefield following the October Revolution in 1917, Berlin quickly identified a six-month window of opportunity. German general officers understood that they benefited not only from the Brest-Litovsk armistice, but also from the slow arrival of the American Expeditionary Forces. They knew that this manpower advantage would disappear as soon as American forces were ready to fight. They estimated that this would come to pass in the summer of 1918. This reasoning led to the German Spring Offensives of 1918, which brought back open warfare.

In a certain way, the Second Battle of the Marne underlined the German failure to reach Paris during this window of opportunity. Not only were Germans exhausted, the country was dealing with political and starvation issues, and was also unable to reinforce its troops. Historian Michel Goya points out that the French army was at that time the most modern army in the world, because it was the most mechanical. It is also true that on the battlefield, poilus, just like Tommies and Doughboys, suffered heavy losses as a result of open warfare. But the main difference is that after the Second Battle of the Marne, around July 1918, General John J. Pershing (1860-1948) was able to promise reinforcements of up to 100 divisions, figures that Germany could no longer compete with.

National Memory↑

The contrast between the transnational history of the Second Battle of the Marne and its memory is striking. In France, these battles, which are seen almost exclusively from a French point of view, are often referred as a second “miracle”, after the first one of September 1914. In the memory of both, French territory and French troops are depicted as the key places and actors in the war against Germany. Thought and memory suggest that France was the main country fighting against Berlin during World War I, so is the main winner, if not the only winner, of the conflict.

For Germans, the key moment of the 1918 debacle might not be the Second Battle of the Marne but 8 August 1918, during the Battle of Amiens, which is still known, after General Erich Ludendorff’s (1865-1937) famous words, as the “black day of the German army”. The key role of General Douglas Haig’s (1861-1928) British Expeditionary Force in what appears to have been the very beginning of the Hundred Days Offensive may explain why the Second Battle of the Marne is quite forgotten.

In the United States, the Second Battle of the Marne is not well known, unlike Belleau Wood, the Saint-Mihiel salient or the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, although the 1st infantry division, as portrayed in the film The Big Red One, played a big role in this counter-attack. Ironically, the American Monument that stands in Meaux, Seine-et-Marne, commissioned by Americans, refers to the First Battle of the Marne, in which no Doughboy fought.

The two battles of the Marne can be seen as culminating points of the German advance on French soil, which resulted in severe German defeats. While the outcome of the battle in 1914 allowed the allies to continue the war, four years later, the Second Battle of the Marne enabled them to consider the eventuality of an end to the conflict. Although German defeat was not inevitable after July 1918, the constant growth in American ranks made an allied victory more probable with each passing day. The memory of the battles does not reflect the transnational aspect of the events. In France, in the United Kingdom, in the United States and in Germany, the Second Battle of the Marne is always understood, not to say remembered or forgotten, from a strictly national point of view.

Erwan Le Gall, Université Rennes 2

Section Editor: Emmanuelle Cronier

Selected Bibliography

- Contamine, Henry: La victoire de la Marne, 9 septembre 1914, Paris 1970: Gallimard.

- Goya, Michel: Les vainqueurs. Comment la France a gagné la Grande Guerre, Paris 2018: Éditions Tallandier.

- Herwig, Holger H.: The Marne, 1914. The opening of World War I and the battle that changed the world, New York 2009: Random House.

- Neiberg, Michael: The second battle of the Marne, Bloomington 2008: Indiana University Press.