Introduction↑

Historian David M. Kennedy aptly noted in Over Here: The First World War and American Society, his classic overview of the American war experience, that “Americans went to war in 1917 not only against Germans in the fields of France but against each other at home.”[1] The entanglement of the United States in the European-instigated conflict vividly reveals the global dimensions of the First World War. The war also made a lasting impact on the domestic development of the United States. Mobilizing for war, Americans found it difficult to put aside their differences over economic inequities, state power, female suffrage, civil rights, immigration, social welfare and the nation’s growing imperial reach. Multiple segments of American society hoped to use the war to gain the upper hand in these debates, and some succeeded.

Neutrality↑

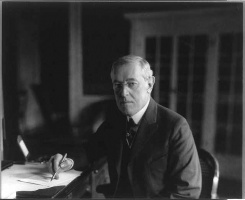

When war exploded across Europe in August 1914, U.S. President Woodrow Wilson (1856-1924) made a decision to stay neutral. Neutrality proved difficult to maintain, however, and for two and a half years the United States found itself caught in a series of diplomatic crises that gradually edged the nation nearer to war. Whether Wilson chose to ask Congress to declare war in April 1917 due to the nation’s strong financial ties to the Allies, growing concerns about increased German aggression, or a desire to shape the peace continues to evoke debate among historians of the American war effort.[2]

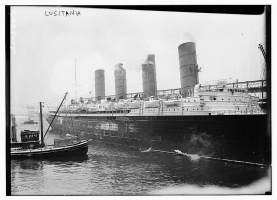

During the period of neutrality, the United States quickly found itself embroiled in the escalating violence that transformed a European war into a global conflict. With European armies locked in a stalemate along the Western Front, in 1915 both Britain and Germany tried to gain the advantage by using their navies to disrupt the trade of their enemy. The British established a naval blockade that included mining the North Sea, while Germany turned to its new weapon, the U-boat (submarine), to launch surprise attacks against merchant and military vessels approaching Great Britain. Both tactics immediately affected the United States by disrupting its trade with Europe, although only German U-boats threatened American lives. This proved a fateful distinction as the United States passed through a series of diplomatic crises related to the naval war.

Germany’s intermittent policy of unconditional submarine warfare dramatically worsened relations with the neutral United States. Wilson protested that unconditional submarine warfare (which relied on undetected and submerged U-boats firing torpedoes) denied civilian passengers the internationally sanctioned right to vacate a merchant ship before its cargo was sunk. On 7 May 1915, a torpedo fired by a German U-boat sank the Lusitania, a British passenger ship, and killed 1,198 passengers, among them 127 Americans. The extensive publicity surrounding the Lusitania sinking prompted much domestic debate over what neutrality meant. Wilson demanded that Germany pay reparations and accept the right of Americans to travel on any ship they wished. Wilson interpreted neutrality as bestowing irrevocable rights that gave neutral nations the right to travel and trade where they wished. Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan (1860-1925) disagreed. He viewed neutrality as staying above the fray to avoid war. Bryan soon resigned in protest when it became clear that he and the president did not share the same views on neutrality.

Bryan represented a significant segment of American opinion in 1915, especially portions of the Midwest and South that opposed any involvement in the war. German-American farmers openly criticized a British blockade policy that reduced food for civilians and often flouted international law. Millions of other rural folk saw the makings of a “rich man’s war, poor man’s fight” as a preparedness movement formed to lobby for increased funding for the peacetime army. Anti-interventionists worried that northeastern banks and businesses were pushing the nation into war to continue their profitable war trade with Great Britain and ensure repayment of war loans.[3] Leading female reformers joined the Women’s Peace Party to seek a diplomatic solution to the war. They also offered a new argument for female suffrage by claiming that women’s peaceful dispositions would strengthen the pacifist voice in foreign policy decisions. Urban elites, however, strongly endorsed Wilson’s diplomatic efforts to protect the nation’s honor and economy by bringing Germany into line. At this point, the dividing line within the American population was over how vigorously to pursue economic opportunities created by a bottomless war trade, not direct intervention, which was a step that few Americans considered either possible or desirable.

In 1915 and 1916 Germany diffused growing diplomatic tensions over unconditional submarine warfare by temporarily halting surprise attacks on merchant and passenger ships. The recurring crises with Germany, however, convinced Wilson that oceanic physical barriers were no longer enough to protect the United States. Wilson’s proposals to change the rules of international politics thus served two complementary goals. Wilson viewed peace without victory, spreading democracy, and establishing a league of nations to handle international disputes as innovations that would terminate the current conflict and, as importantly, ensure the national security of the United States by rendering another European-instigated global war impossible.[4]

The independent financial ties that American banks established with the Allies tied American economic fortunes to the war. Throughout the period of neutrality American banks disproportionately financed the Allied war effort. In January 1915, the financial giant J.P. Morgan became the purchasing and contracting agent for the British government within the United States. Over the next two years, the House of Morgan worked closely with British military and financial officials to award more than 4,000 contracts worth over $3 billion to American businesses. In addition, American bankers extended commercial credit to the Allies that averaged nearly $10 million a day.[5] By 1916, American trade with Germany was less than 1 percent of what it had been in 1914, but had tripled with Britain and France. Strong financial ties did not guarantee a trouble-free relationship between Britain and the United States, however. As tension with Germany eased in 1916, relations between the United States and Britain worsened in the wake of Britain’s decision to blacklist American firms that traded with Germany and the violent suppression of the 1916 Irish Easter Rebellion.

By 1917 a credit crisis loomed that threatened to cut off Britain’s access to American goods and financing. The British had exhausted their capacity to borrow money against secured assets, prompting the Federal Reserve to caution U.S. bankers against making further unsecured loans.[6] “Lack of credit was about to crimp and possibly cut off the Allies’ stream of munitions and foodstuffs,” historian John Milton Cooper, Jr. contended.[7] Such a move was potentially catastrophic for the Allies since Britain funnelled money borrowed from the United States to other Entente nations like France and Russia. Scholar Hew Strachan remained sceptical that Wilson would have ended a financial partnership that greatly benefited the American economy.[8]

In Germany’s eyes, the privileged trade and financial relations between the United States and the Allies undermined the Americans’ claim of neutrality. Perceiving that the United States had already chosen sides, Germany accepted the risk of a formal rupture in diplomatic relations by resuming unconditional submarine warfare on 31 January 1917. Wilson formally broke diplomatic relations with Germany on 3 February 1917, a move that did not panic German leaders. They expected the unfettered use of submarines to disrupt overseas trade, putting enough economic pressures on the Allies to end the war quickly. Attacking U.S. troop ships if the United States entered the war would further limit any potential American presence on the Western Front.

American Entry into the War↑

Anticipating this hostile American response, German Foreign Minister Arthur Zimmermann (1864-1940) attempted to distract American attention from Europe by stirring up tensions between the United States and Mexico. On 16 January 1917 he sent a telegram, which subsequently became known as the Zimmermann Telegram, to the German ambassador in Mexico, instructing him to offer German aid to help Mexico regain territory ceded to the United States in the mid-19th century. “Mexico’s hatred for America is well-founded and old,” Zimmermann assured his German colleagues, predicting a long, drawn-out border war between Mexico and the United States that would keep American troops tied down in North America, thus reducing the number of U.S. soldiers available to fight along the Western Front.[9] The Zimmermann Telegram instead proved a public relations debacle for Germany after the British intercepted, decoded, and then passed the telegram onto the American government. The attacks on American-flagged ships, some traveling westbound from Europe, gave credence to the argument that the United States was under attack.[10] On 6 April 1917, the United States declared war on Germany. It did not declare war on Austria-Hungary until December 1917 and was never at war with the Ottoman Empire.

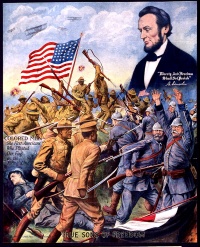

In his 2 April 1917 war address, Wilson presented the war as one of national defense: “We enter this war only where we are clearly forced into it because there are not other means of defending our rights.” Wilson saw the war as a chance to remake the world in the image of the United States. America, he declared, had “no quarrel with the German people.” Instead, the United States was fighting against the “little groups of ambitious men” who used the German people as pawns to aggrandize their power. Wilson succinctly framed the war’s purpose in one phrase that has resonated in American foreign policy ever since. The world, he declared “must be made safe for democracy.” [11]

Wilson offered a more comprehensive description of this new world order when he delivered his Fourteen Points speech to Congress on 8 January 1918. The Fourteen Points envisioned a world dominated by democracy, free trade, disarmament, self-determination, resolved territorial disputes in Europe, and a league of nations to mediate international crises. Wilson explicitly linked the spread of democracy with the expansion of capitalism, a position that gained new urgency when the successful Bolshevik revolution in Russia presented communism as a viable alternative. The Fourteen Points thus married democracy to capitalism, anticipating a future in which the United States wielded tremendous influence over the global economy and international relations.

Scholars agree that Wilson’s vision shaped 20th century American foreign policy, but they differ on whether it left a positive or negative legacy. Lloyd E. Ambrosius lamented that Wilson’s willingness to use war to spread American-style democracy and capitalism gave birth to a destructive messianic impulse that would justify countless American interventions throughout the world in the 20th century. Wilson biographer John Milton Cooper, Jr. disagreed, arguing that Wilson established fundamentally sound democratic values to guide foreign policy decisions. Both scholars agreed that future American presidents as diverse as Harry Truman (1884-1972), Lyndon Johnson (1908-1973), and Richard Nixon (1913-1994) accepted Wilson’s premise that America’s national security depended on spreading democracy and active engagement in the world.[12]

Wilson expected the American army to make a contribution to the fighting underway along the Western Front, thus earning him a key role in shaping the peace settlement. The United States had made few preparations for war during the period of neutrality. It now faced the challenge of raising a mass army, transporting it overseas, mobilizing the economy to support the expeditionary force, and unifying a divided public behind the war effort. Mobilizing for war, however, proved as tumultuous as making the decision to fight.

Creating an Army and Mobilizing the Home Front↑

By 1917, Americans’ participation in the global conflict already went beyond arguing about the merits of intervention, lending money to the Allies, or trading with belligerent nations. Thousands of Americans were in Europe as aid workers or fighting within Allied armies.[13] Hundreds of thousands at home had donated money, food, and clothing to the massive international relief efforts underway to alleviate civilian suffering. What Americans had done voluntarily during the period of neutrality, however, the state would now compel.

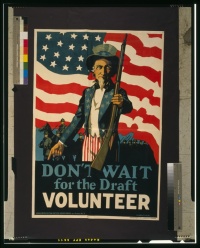

The government chose to raise the bulk of the required forces, nearly 72 percent, through conscription, breaking with the nation’s tradition of waiting for enlistments to wane before instituting a draft. A draft offered several political and manpower advantages over raising a strictly volunteer force. Communities bore the responsibility for registering and selecting men for induction into the army. To make the draft less controversial, the government avoided sending federal agents into towns to induct men. Instead “friends and neighbors” served on local draft boards to select fellow townsmen to meet federal troop quotas. Fashioning a cooperative town-state-federal partnership to conscript the army obscured the enlarged powers conscription granted to the federal government.

By making the draft more politically palatable, the federal government ensured that the army would receive a steady stream of new troops even when news of casualties began to filter home. Under the watchful eyes of community leaders, draft-age men faced considerable pressure to comply with draft registration and induction notices. Federal officials also viewed the draft as an effective method for channeling laborers into essential war-related industries. For instance, if a laborer received a draft deferment for working on the railroads and then quit his job, he risked induction into the army. The draft thus served as a way to mobilize the entire male draft-age population in service of the war, through either industry or military service.[14] Resistance to conscription did occur, especially in the South, with 3 million, or 11 percent, of the draft-eligible male population failing to register or report to induction centers once called into service. Another 20,000 men served as conscientious objectors, liable only for non-combatant service.[15] Overall, however, the draft functioned well enough to mobilize the uniformed manpower needed to field an overseas force.

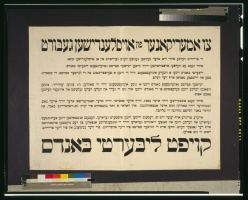

The federal government erected a host of agencies to direct home front mobilization, and as with the draft, they relied on active citizen support within communities to enforce federal directives. The Committee on Public Information (CPI) was charged with controlling the flow of information to shape public opinion about the war. The agency disseminated patriotic posters, pamphlets, and films to keep a war fought far from U.S. shores in the forefront of the American imagination. The success of this propaganda effort depended on the willingness of storeowners, newspapers, and movie theaters to display these materials. The CPI also recruited so-called Four-Minute Men (named for the time that it took to change reels for silent movies) to speak before audiences in movie halls, markets, fairs, and churches about the causes of the war, its progress, and how to identify German spies. Citizens, ranging from songwriters to calendar makers, produced and distributed their own patriotic propaganda in support of the war. These official and unofficial efforts made the war highly visible in everyday life.

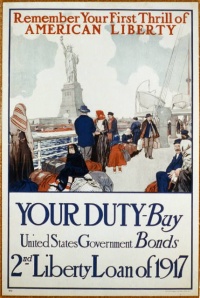

To help pay for the war, the government encouraged Americans to buy a $50 liberty bond, a $5 war savings certificate, or a twenty-five cent thrift stamp. Secretary of the Treasury William Gibbs McAdoo (1863-1941) had more in mind than just financing the war by organizing national war bond drives. “Any great war must necessarily be a popular movement,” McAdoo noted. “It is a kind of crusade; and like all crusades, it sweeps along on a powerful stream of romanticism.”[16] Instead of bankrolling the war exclusively through higher taxes, the government wanted citizens to use their money to connect personally with a distant war. Overall, the four liberty loan and one victory loan campaigns raised $21.4 billion for a war estimated to have cost the United States $32 billion.

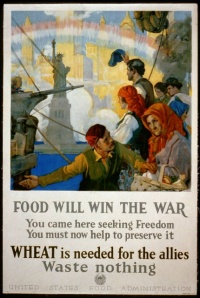

The Food Administration relied on propaganda to organize a massive food conservation crusade around the slogan “food will win the war.” Local citizens groups went door-to-door asking women to sign pledges observing wheatless Mondays, meatless Tuesdays, and porkless Saturdays to save food for the troops. Those who complied received a placard to place in their window, analogous to the starred flags that families with a male relative in the armed forces hung for their neighbors to see. Publicly displaying signs and flags advertised a household’s active support for the war. These symbols also helped single out those citizens who remained opposed or uncertain about the war. The success of food conservation drives depended on the willingness of local public safety committees to encourage, entreat, and sometimes even insist that area residents comply. Like war bond drives, food conservation campaigns served primarily to create an aura of public support for the war. As a method for conserving food, these massive propaganda and pledge campaigns fell short. Higher wages for workers during the war meant that domestic meat consumption actually increased. Incentives offered to food producers such as low-cost loans and higher commodity prices (which the Food Administration negotiated with Allied purchasers) spurred an increase in crop and livestock production that met domestic and overseas demand.[17]

Mobilizing Capital and Labor↑

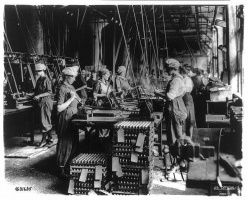

The concept of the citizen-soldier serving the nation in time of war was a well-established American political tradition. Substantial disagreement existed, however, over the benefits of a federally-managed economy. Equipping the army required convincing civilian-based manufacturers to re-tool their plants to produce needed weapons of war. The wartime relationships between individual industries and government officials defied easy categorization. Some were harmonious, others contentious. The government could not force a car factory to switch to making tanks, so as with farmers, government incentives encouraged manufacturers to meet wartime needs. The War Industries Board, for instance, ranked industries so that those most critical to the war effort received raw materials ahead of nonessential wartime businesses. The agency also established industrial committees to set price and production codes, and became the purchasing agent for Allied governments.

Before the war, progressive reformers had initiated a drive for increased governmental regulation of the economy to contain the growing economic and political influence of corporations and banks. Many reformers supported the war, partly in hopes that government management of the wartime economy would demonstrate the positive effects of centralized, economic planning.[18] The active cooperation needed from business to mobilize the wartime economy instead granted business elites a golden opportunity to derail the momentum of pre-war regulatory reform movements. By the end of the war, the government had turned away from a governing model that relied on regulation to punish big business and protect the public. The experience of wartime mobilization served to energize a new post-war faith that the government could build cooperative, friendly alliances with business to protect the common good.[19] Liberal Democrats never lost their faith in the efficacy of centralized planning, however. During the New Deal, reformers recalled the wartime experiments in price, production, and wage controls, and used them as models when formulating New Deal recovery and economic management policies in the 1930s.[20]

Wartime mobilization abetted the growth of politically moderate labor unions. The National War Labor Board (made up of representatives from government, business, and labor) required industries that accepted government contracts to recognize and negotiate with unions, and honor the eight-hour day and forty-hour week. Workers received high wartime wages, but after adjusting for the considerable inflation, real wages only increased 4 percent.

The government built housing in areas deluged with an influx of war workers and created employment bureaus to funnel workers into manufacturing sectors experiencing labor shortages. “Although progressive reformers viewed the war-created emergencies as an opportunity to involve the government permanently in such areas as housing, social welfare, and medical care, popular forces in support of a modern welfare state were too weak to sustain these experiments in public action,” noted historian Robert H. Zieger.[21] When the war ended and the government canceled its contracts, workers also lost governmental support for their right to organize unions. Without the government stopping them, many manufacturers quickly returned to their old union-busting ways. Unions matched the determination of capitalists to gain the upper hand in post-war industrial relations. The wartime growth in union ranks and workers’ desire to retain gains in wages, hours and workplace control powered a slew of strikes. In 1919, nearly 20 percent of the workforce was involved in work stoppages. As in the past, companies organized physical assaults on picketing workers, appealed to racial and ethnic prejudices to divide workers against each other, and replaced striking workers with scabs (including returning soldiers looking for work). In the end, the labor movement’s wartime momentum ground to a halt – a victim of the post-war recession, employer intransigence, increased federal surveillance of radical labor groups, and divisions within their own ranks.[22]

Suppressing Dissent↑

During the period of neutrality, Americans could freely voice their opposition to fighting against Germany. Once the nation entered the war, however, the government curbed dissent. The 1917 Espionage Act made it a crime to obstruct military recruitment, to encourage mutiny, or to aid the enemy by spreading lies. The 1917 Trading with the Enemy Act required foreign publications to submit English-language translations of articles about the war. The 1918 Sedition Act prohibited uttering, writing, or publishing “any abusive or disloyal language” concerning the flag, constitution, government, or armed forces. Upholding the constitutionality of the Espionage Act in Schenck v. United States (1919), the Supreme Court agreed that Congress could curtail speech that created a “clear and present danger.” Writing for the majority, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. (1841-1935) concluded that “when the nation is at war many things that might be said in time of peace...will not be endured so long as men fight.”[23]

Already suspect for their leftist, anti-capitalist beliefs, radical groups like the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) and the Socialist Party experienced the suppressive power of the wartime security state firsthand. The postmaster general invoked the Espionage Act to ban their publications through the mail. Military intelligence operatives infiltrated their meetings, and arrests of key leaders decimated these organizations. Black civil rights organizations also came under suspicion, with federal agents assembling large files detailing how “German spies” were responsible for stirring up racial unrest. The American Protective League recruited local residents to work with state and federal agents to police their communities, demonstrating the role that average citizens played in helping the nascent security state extend its power and reach into Americans’ daily lives.

The most prominent dissident arrested was Eugene Debs (1855-1926), who had received 900,000 votes (6 percent of the popular vote) when he ran on the Socialist ticket for president in 1912. Debs was arrested, convicted, and jailed for delivering an anti-war speech on 15 June 1918 in Canton, Ohio, during which he described the war as a capitalist rivalry for international markets and raw materials. His conviction only increased his notoriety, turning Debs into a martyr for the left. He ran again for president from his jail cell in 1920 and received 1 million votes. President Warren Harding (1865-1923) finally pardoned him in 1921.

The Socialist Party survived the war, but the IWW did not. Dedicated to forming “one big union” that would eventually take over the means of production, the IWW thrived in western mining and lumbering areas where worker exploitation ran rampant. The federal crackdown on sedition offered local elites an opportunity to take up arms against the long detested IWW without fear of sanction. A mere three months after the nation entered the war, and two months after the passage of the Espionage Act, local police and businessmen forcibly herded striking copper mine workers in Bisbee, Arizona into railroad cars and then marooned them in the New Mexico desert. Although a subsequent government report criticized the extralegal vigilantism, major newspapers and political figures defended the Bisbee deportation by accusing the striking workers of trying to sabotage the war effort. Moderate and conservative labor unions, hoping to demonstrate their own loyalty and hasten the demise of their competitors, raised few objections to these physical and legal assaults on the IWW and Socialists.

The National Civil Liberties Bureau (NCLB), Socialist Party and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) fought back throughout the war to protect the right to free speech. They filed lawsuits and publicized the extent of government surveillance and harassment of left-leaning organizations and publications. The NCLB formed in 1917, drawing members from the defunct American Union Against Militarism (1914-17) which disbanded when the United States entered the war. These activists focused on protecting the constitutional rights of dissenters, including contentious objectors. The war was a formative moment for the civil liberties movement. In 1920 the NCLB became the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) which continues to use the courts to challenge the government’s right to curtail civil liberties in the name of national security.[24]

Immigrants and the War↑

State prosecutions and harassment of dissidents created an environment where individuals began to self-censor their activities to avoid coming under suspicion. During the two and a half years of debate over whether the United States should enter the war, many German Americans had freely expressed their support for Germany within a vibrant ethnic culture rooted in German-language civic organizations, churches, publications, newspapers, music, and schools. A torrent of legal and physical attacks during the war effectively muzzled German Americans and fragmented their communities.

In the wake of the declaration of war, Wilson classified German immigrants over the age of fourteen as enemy aliens who had to surrender all firearms and wireless radios, as well as register for Selective Service so the government could monitor their whereabouts. They were also prohibited from living next to military installations. Schools banned German-language instruction, orchestras stopped playing German music in public, and towns drew up laws that prevented aliens from voting. In a few well-publicized cases, mobs attacked non-conformist German immigrants, men whose radical political opinions or acerbic personalities made them appealing targets for self-appointed patriotic defenders. Amid these official and unofficial demands for 100 percent Americanism, many German Americans voluntarily silenced themselves. German speakers canceled their subscriptions to German-language publications, changed their names, stopped worshiping in German, and disbanded fraternal clubs. Self-censorship served as a form of self-defense.[25]

The German American experience, however, was not representative of how all foreign born lived through the war years. Immigrants from Allied nations had little trouble maintaining loyalty to both their ethnic heritage and their new homeland. For them 100 percent Americanism meant demonstrating a complete commitment to winning the war, not forgoing all cultural or political connections to their country of birth. Unifying to support the war created new bonds among immigrants from the same country, allowing Sicilians and Romans, for instance, to develop a shared “Italian” identity that overshadowed previous regional distinctions.[26] The war also offered new ways for immigrants from Allied nations to participate in mainstream American culture. The government targeted foreign-speaking communities through propaganda materials printed in a variety of languages, and ethnic leaders eagerly stepped forward to serve on the local committees organizing food conservation and war bond campaigns.

Foreign born residents from Allied nations frequently supported the war for different reasons than native born Americans. Immigrants raised funds for civilian refugees in their homelands and took a vivid interest in the outcome of territorial disputes in their birthplaces. With millions harking from Southern and Eastern Europe, immigrants often paid more attention to the war beyond the Western Front. The British promise to establish a Jewish homeland in Palestine, for instance, offered additional motivations for Jews to support the war.

Newly visible in mainstream culture, foreign born populations from Allied nations received praise for their overt displays of loyalty to the United States. Nearly one in five soldiers who fought in the American army was foreign born, turning military service into a caldron where men from forty-six different nationalities met and learned to be “American.”[27] Contemporary commentators perceived participation in the national wartime culture as hastening the process of assimilation, ignoring the ways that immigrant community mobilization in support of the war strengthened ethnic identities.

This display of wartime loyalty by America’s immigrant communities failed to stem the momentum growing for stricter immigration laws. Instead, the wartime notion that unfettered immigration threatened national security prevailed. In the early 1920s, the nation embraced a series of strict immigration restrictions that established quotas to regulate how many people emigrated annually from individual European nations.

Reform Movements and the War↑

Social welfare reformers saw the war as an opportunity to advance their crusade for improving the moral, physical, and intellectual tenor of American society. Working through the auspices of the Commission on Training Camp Activities (CTCA), social welfare reformers launched a federally sanctioned assault against venereal disease and prostitution. Reformers presented their longstanding anti-vice campaign as a measure that protected manpower (in this pre-penicillin age, men with venereal disease could not serve overseas). CTCA officials closed down red-light districts and devised sex education programs to alert men to the symptoms of venereal disease. They introduced organized, competitive athletics into the military training regime to distract men from seeking women and drink. Winning the war became the trump card that these reformers played whenever they encountered local resistance to their reforms. Throughout the war, CTCA reformers ignored local statutes prohibiting Sunday entertainment and dismissed Catholics’ concerns about the explicit sex education films distributed by the agency. Viewing the CTCA’s zealousness as a dangerous extension of federal power, mounting local opposition ensured that the federally supported anti-vice initiative ended with the war.[28]

The wartime emphasis on worker efficiency, conserving grain, and keeping alcohol away from soldiers in uniform hastened the adoption of the 18th Amendment (1919) to the U.S. Constitution. The 18th Amendment banned the sale, manufacturing, and transportation of intoxicating liquors. Temperance, the longest reform movement in the United States, thus achieved a major milestone by convincing the nation that abolishing alcohol would usher in a post-war era of prosperity and improved home life.

The quest for efficiency also led to the introduction of intelligence testing within army camps. The attempt to use a merit-based approach to fill the wide array of combat and bureaucratic positions revealed the difficulty of staffing an increasingly complex military establishment. The tests revealed the poor state of public education in many southern states, helping Progressives achieve another long-sought goal when all states adopted mandatory schooling laws after the war.

The African American Experience↑

The war was a transformative moment for the civil rights movement, a time when the black community acquired not just the motivation but also the means for launching assaults on Jim Crow.[29] The Great Migration, a major demographic shift, occurred when over 500,000 African Americans relocated from the south to the north. Conscription and the interrupted flow of immigrants from Europe created a labor shortage in the booming industrial north, and labor recruiters headed south to find workers to fill factory vacancies. The influx of African Americans into northern cities sparked several violent racial clashes, the most deadly occurring in East St. Louis in July 1917 and in Chicago and Washington, D.C. in 1919.

These race riots demonstrated that racial prejudice was a national, not just regional, problem. Nonetheless the ability of blacks to vote in the northern states meant that the Great Migration led to an expansion of black political power, providing a toehold that would prove important in future civil rights campaigns. Similarly, the emergence of Harlem as a mecca that drew black musicians, artists, and writers harking from different regions of the United States and the West Indies contributed to a post-war flourishing of African American artistic expression.[30] Community-based mobilization during the war, whether to rally the black community to buy war bonds or to protest discriminatory treatment of African American soldiers, also benefited the civil rights movement. New leaders emerged, membership in fledgling groups like the NAACP grew, and the war’s democratic rhetoric infused the movement with a new ideological focus. Returning black soldiers, angry about the racial discrimination they encountered within the segregated wartime army, helped form an ethos of “fighting back,” both literally and figuratively, which laid the foundation for a more militant civil rights movement.

Women and the War↑

Mobilizing the home front meant securing active cooperation from women. Overall, few women entered the workplace for the first time during the war. Instead, the 8 million women already at work had opportunities to shift into better paying and higher skilled jobs. Most women, however, lost these better positions when the war ended and soldiers returned home. Middle-class women, who had the leisure time to belong to an array of social clubs, proved essential grassroots organizers in mobilizing local communities across the nation. They spearheaded the Red Cross campaign that enlisted over 8 million female volunteers to knit socks and roll bandages for the troops, and helped the Food Administration distribute recipes that conserved items like wheat and sugar.

Over 16,500 women also donned military uniforms; most worked as telephone operators, typists, and nurses. The military utilized women out of necessity, but tried to avoid any redefinition of societal gender roles by placing these women under male supervision. By recruiting female workers who were ten years older than the average American soldier, the military hoped to encourage maternal, rather than romantic, relations between the sexes.[31]

The well-publicized image of an engaged female citizenry actively working to defend the nation directly benefited the suffrage movement. Divided into factions, female suffragists employed different tactics to send the same message: women deserved the right to vote. The militant arm, represented by the National Women’s Party, openly challenged Wilson to stand by his democratic rhetoric. They pioneered a new protest technique by picketing the White House with banners asking “how long must women wait for liberty?”[32] The more conservative National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) followed a different tack, presenting the right to vote as a way for loyal women to protect their families and nation. “It is a risk, a danger to a country like ours to send 1,000,000 men out of the country who are loyal and not replace those men by the loyal votes of the women they have left at home,” NAWSA president Carrie Chapman Catt (1859-1947) proclaimed. [33] The ratification of the 19th Amendment in 1920 ended a decades-long campaign to secure female voting rights.

The American Military Contribution↑

By the time the war ended on 11 November 1918, the United States had managed to raise an army of over 4 million men, transport 2 million to France, and command a field army of 1.2 million in major offensive operations along the Western Front. Despite these significant achievements, the army paid a price for its inexperience and unpreparedness. American-commanded operations in the last four months of the war (when the United States took over its own sector of the Western Front) were hampered by disorganization in the rear, high casualty rates, and constantly changing leadership. These problems were symptomatic of an army forced by circumstances to fight before it was fully trained and formed.

America fought one of the bloodiest battles in its history during World War I. The forty-seven-day Meuse-Argonne Offensive lasted from 26 September to 11 November 1918, engaging 600,000 men, 4,000 artillery guns and 90,000 horses on the opening day. Nearly 45,000 men were killed and wounded in the first four days of the battle, and more U.S. troops died in September and October 1918 than in any other single month during the Civil War or World War II.

Much controversy surrounds the question of what ultimate role the United States played in winning the war. American scholars assign the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) all credit for the ultimate victory; others practically none.[34] The consensus view holds that the infusion of American troops helped stem the 1918 German spring offensives and fueled the overall Allied fall advance. The prospect of millions more Americans arriving in 1919, the effectiveness of the convoy system, and the importance of ongoing American financial support also prompted the German decision to request an armistice.

Wilson and Peace↑

Maintaining American independence of action by fighting as an Associate Power rather than formally joining the Allies, sending a large army overseas, and resisting pressures to amalgamate American armed forces into the British and French armies were all decisions that Wilson made with an eye on maximizing his role at the eventual peace conference. Wilson arrived in Paris with the goal of remaking the global world order through self-determination, open trade, and collective security. How well the American public understood Wilson’s vision was another matter.

Serving as a war president had caused Wilson to modify his 1917 call for a “peace without victory” even before he sat down at the negotiating table. During the period of neutrality Wilson envisioned himself serving as an umpire between the victorious and vanquished. He began shifting his views in the Fourteen Points when he accepted Allied territorial ambitions and broadened his concept of self-determination beyond restoring political independence to occupied lands. By November 1918, Wilson was sitting firmly on the victor’s side of the table. He now believed that Germany had to recognize its wartime wrongdoing and accept a regime change. Wilson, however, steadfastly refused to acknowledge any deviation in his thinking from his original peace proposals. Nor did he feel the need to explain to the American public why the realities of international geopolitics made some concessions necessary during the peace treaty negotiations. These political failings opened Wilson up to subsequent charges that he was a fraud without integrity who had abandoned his principles or an inept diplomat duped by wily European leaders into agreeing to a punitive peace treaty.[35]

Wilson arrived in Paris with his political stature somewhat diminished. Allied leaders viewed Republican gains in the 1918 midterm congressional elections as evidence of Wilson’s declining domestic popularity, emboldening them to challenge him more forcefully. In his 1920 bestseller, The Economic Consequences of the Peace, British economist John Maynard Keynes (1883-1946) offered a scathing characterization of Wilson as a bumbling, “contemptible hypocrite” hoodwinked by savvy European statesmen in Paris. He described the Versailles Peace Treaty as a Carthaginian peace that inflicted undue hardship on Germany, setting an interpretative framework for understanding Wilson’s role in shaping the peace that endured for decades.

Wilson, however, was not blind to the treaty’s flaws. The president’s compromises on the Versailles Treaty reflected the political strength that Wilson’s political adversaries (both overseas and at home) wielded.[36] He believed that over time, as passions cooled, the League would provide a venue for ameliorating the treaty’s most punitive aspects.

The harshness of the treaty bothered some Americans, but this was not the major objection to ratification. Far more troubling was Wilson’s inability to offer a clear rebuttal to Senate Republican criticism of Article X of the League of Nations Covenant. This clause contained a pledge to “undertake to respect and preserve as against external aggression the territorial integrity and existing political independence” of fellow League members. Wilson believed that the League would prevent another general war by giving member nations a place to mediate international disputes and coordinate joint military actions to contain aggressor nations. Many Republicans, however, disagreed with the Democratic president’s rosy predictions of permanent peace. Opponents worried that the United States might lose control of its own foreign policy, transferring the power to declare war from Congress to the League’s governing council. Membership might also invite international scrutiny of U.S. armed interventions throughout Central America where the United States had become accustomed to acting unilaterally.

Wilson countered that the League only had the power to advise member governments; it could not compel any nation to send troops overseas. His focus on the impracticality of calling upon American troops to handle European-based disputes obscured the major question at hand, however. In defending the treaty Wilson refused to acknowledge that accepting such an encompassing international role represented a dramatic shift in American foreign policy.

Taking the treaty fight directly to the American people, Wilson undertook a massive cross-country speaking campaign. On 27 September 1919, he suffered a crippling stroke that left him invalided for months. The White House kept his illness a secret, and once Wilson returned to work he steadfastly refused to accept any Senate-added reservations to the treaty. These reservations included reaffirming Congress’s right to declare war, the right to withdraw from the League, and international recognition of the Monroe Doctrine which defined the United States as the guardian of the Western Hemisphere. Whether he was making a principled stand, revealing his stubbornness, or suffering from stroke-inducted impairment of judgment continues to provoke debate among Wilson scholars. With the president and Senate Republicans unable to come to an agreement, the United States Senate rejected the Versailles Treaty. Instead, the Senate ratified separate peace treaties with Germany, Austria, and Hungary in October 1921.

The Senate’s ultimate rejection of the Versailles Treaty did not, however, represent a wholesale rejection of Wilsonian internationalism or a retreat into isolationism. The Wilsonian vision of an engaged United States crafting diplomatic solutions to world crises remained intact throughout the 1920s. In the interwar years, the nation exerted world leadership in negotiating disarmament pacts, the restructuring of reparation payments, and an international agreement prohibiting aggressive war.

Memory and World War I↑

World War I occupied a central place in American cultural and political life from 1918-1945. The United States devoted considerable resources to commemorating its involvement in the war. In 1921 the government dedicated the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in Arlington National Cemetery, and then created large overseas cemeteries to remind Europeans of America’s sacrifice. In 1929 Congress authorized a federally funded pilgrimage by mothers and widows to visit their sons’ overseas graves. A steady flow of war-related literature, art, film, and memorials also appeared. Americans did not agree, however, on what they were remembering.[37] Throughout the 1920s and 1930s debates raged over whether the war was an epic tragedy, a heroic coming of age for individuals and the nation, or a “rich man’s war, poor man’s fight.” The interpretation of the war as an epic tragedy inspired a raft of neutrality laws in the 1930s aimed at preventing American involvement in another European war. The view of the war as a “rich man’s war, poor man’s fight” spurred intense veteran lobbying for increased financial compensation and benefits, leading to a mass Washington, D.C.-based protest in 1932 known as the Bonus March. The notion that the war represented a rite of passage permeated multiple arenas of American life, with the crucible of war seen as giving birth to the New Negro, the Lost Generation, the New Woman, and the United States as a premier power.

Interest in World War I, however, waned considerably after 1945. The U.S. victory in World War II signaled unambiguously the arrival of the American century, overshadowing World War I in significance. In many respects World War I became a “forgotten war” within American culture with no clear narrative that explained its importance in shaping the nation. Rekindling interest in the war and demonstrating the war’s impact on American society remains a scholarly work in progress.

Jennifer D. Keene, Chapman University

Section Editor: Edward G. Lengel

Notes

- ↑ Kennedy, David: Over Here. The First World War and American Society, New York 1980, p. 41.

- ↑ For examples of the scholarly debate see: Gregory, Ross: The Origins of American Intervention in the First World War, New York 1971, which noted that disproportionate trading and lending to the Allies increasingly tied American economic prosperity to an Allied victory; Cooper, John Milton, Jr.: Woodrow Wilson. A Biography, New York 2009, who argued that Wilson decided to use war to achieve his larger goal of creating a new structure to govern international relations in the post-war world; and the debate over the relative importance of the Zimmermann Telegram between Katz, Friedrich: The Secret War in Mexico. Europe, the United States and the Mexican Revolution, Chicago 1981, and Boghardt, Thomas: The Zimmermann Telegram. Intelligence, Diplomacy, and America's Entry into World War I, Annapolis 2012.

- ↑ Keith, Jeannette: Rich Man’s War, Poor Man’s Fight. Race, Class and Power in the Rural South during the First World War, Chapel Hill 2004.

- ↑ Kennedy, Ross A.: Woodrow Wilson, World War I, and an American Conception of National Security, in: Diplomatic History 25/1 (2001), pp. 1-31.

- ↑ Zieger, Robert H.: America’s Great War. World War I and the American Experience, New York 2000, p. 30.

- ↑ Koistinen, Paul A.C.: Mobilizing for Modern War. The Political Economy of American Warfare, 1865-1919, Lawrence 1997, pp. 133f.

- ↑ Cooper, Woodrow Wilson 2009, p. 373.

- ↑ Strachan, Hew: The First World War, volume 1, To Arms, Oxford 2001, p. 991.

- ↑ Katz, The Secret War 1981, p. 351.

- ↑ Carlisle, Rodney: Sovereignty at Sea. U.S. Merchant Ships and American Entry into World War I, Gainesville 2010, pp. 34f, 61.

- ↑ Wilson, Woodrow: US Declaration of Neutrality, 19.8.1914. Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=65382 (Retrieved 2 June 2014).

- ↑ Ambrosius, Lloyd E.: Wilsonianism. Woodrow Wilson and His Legacy in American Foreign Relations, New York 2002.

- ↑ See: Bruce, Robert B.: A Fraternity of Arms. America and France in the Great War, Lawrence 2003; and Little, John Branden: Band of Crusaders. American Humanitarians, the Great War, and the Remaking of the World, PhD dissertation, University of California, Berkley 2009.

- ↑ Keene, Jennifer D.: Doughboys, the Great War and the Remaking of America, Baltimore 2001, chapter 1; Chambers, John Whiteclay: To Raise An Army. The Draft Comes to Modern America, New York 1987.

- ↑ Zieger, America’s Great War 2000, pp. 61f.

- ↑ McAdoo, William Gibbs: Crowded Years, Port Washington 1971, p. 374.

- ↑ Capozzola, Christopher: Uncle Sam Wants You. World War I and the Making of the Modern American Citizen, New York 2008, chapter 3.

- ↑ Kennedy, Over Here 1980, pp. 49ff; 88-92.

- ↑ Hawley, Ellis W.: The Great War and the Search for a Modern Order. A History of the American People and Their Institutions, 1917-1933, New York 1979.

- ↑ Leuchtenburg, William: The New Deal and the Analogue of War, in: Braemen, John/Bremner, Robert H./Walters, Everett (eds.): Change and Continuity in Twentieth Century America, Columbus 1964, pp. 80-143.

- ↑ Zieger, America’s Great War 2000, pp. 125f.

- ↑ McCartin, Joseph A.: Labor’s Great War. The Struggle for Industrial Democracy and the Origins of Modern American Labor Relations, 1912-1921, Chapel Hill 1997.

- ↑ Peterson, H. C. / Fite, G. C.: Opponents of War, 1917-1918, Westport 1986, p. 32.

- ↑ Murphy, Paul L.: World War I and the Origins of Civil Liberties in the United States, New York 1979.

- ↑ Capozzola, Uncle Sam 2008, pp. 197-201.

- ↑ Sterba, Christopher M.: Good Americans. Italian and Jewish Immigrants during the First World War, New York 2003.

- ↑ Ford, Nancy Gentile: Americans All! Foreign-Born Soldiers in World War I, College Station 2001.

- ↑ Bristow, Nancy: Making Men Moral. Social Engineering During the Great War, New York 1996.

- ↑ Williams, Chad: Torchbearers of Democracy. African American Soldiers in the World War I Era, Chapel Hill 2010; Lentz-Smith, Adrienne: Freedom Struggles. African Americans and World War I, Cambridge, MA 2009; Keene, Jennifer D.: Protest and Disability. A New Look at African American Soldiers During the First World War, in: Purseigle, Pierre (ed.): Warfare and Belligerence. Perspectives in First World War Studies, London 2005, pp. 215-42.

- ↑ Whalen, Mark: The Great War and the Culture of the New Negro, Gainesville 2008.

- ↑ Zeiger, Susan: In Uncle Sam’s Service. Women Workers with the American Expeditionary Force, 1917-1919, Philadelphia 2004.

- ↑ Schaffer, Ronald: America in the Great War. The Rise of the War Welfare State, New York 1991, p. 93.

- ↑ Schaffer, America in the Great War 1991, pp. 91f.

- ↑ For the range of debate on this issue see: Mosier, John: The Myth of the Great War. A New Military History of World War I, New York 2001, who argued the Americans were responsible for the Allies’ decisive win. On the other side of the pendulum, World War I historians Gary Sheffield, Robin Prior, Trevor Wilson, Tim Travers and Ian Beckett view the American military contribution as negligible. Grotelueschen, Mark: The AEF Way of War. The American Army and Combat in World War I, New York 2006 represents the middle-ground view embraced by most scholars.

- ↑ Schwabe, Klaus: Woodrow Wilson, Revolutionary Germany, and Peacemaking, 1918-1919, Chapel Hill 1985.

- ↑ Walworth, Arthur: Wilson and his Peacemakers. American Diplomacy at the Paris Peace Conference, 1919, New York 1986.

- ↑ Trout, Steven: On the Battlefields of Memory, The First World War and American Remembrance, 1919-1941, Tuscaloosa 2010.

Selected Bibliography

- Budreau, Lisa M.: Bodies of war. World War I and the politics of commemoration in America, 1919-1933, New York 2010: New York University Press.

- Capozzola, Christopher Joseph Nicodemus: Uncle Sam wants you. World War I and the making of the modern American citizen, Oxford; New York 2008: Oxford University Press.

- Coffman, Edward M.: The war to end all wars. The American military experience in World War I, Lexington 1998: University Press of Kentucky.

- Cooper, John Milton, Jr.: Woodrow Wilson. A biography, New York 2009: Alfred A. Knopf.

- Cuff, Robert D.: The War Industries Board. Business-government relations during World War I, Baltimore 1973: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Ferrell, Robert H.: Woodrow Wilson and World War I, 1917-1921, New York 1985: Harper & Row.

- Grotelueschen, Mark E.: The AEF way of war. The American army and combat in World War I, Cambridge; New York 2007: Cambridge University Press.

- Keene, Jennifer D.: Doughboys, the Great War, and the remaking of America, Baltimore 2001: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Keith, Jeanette: Rich man's war, poor man's fight. Race, class, and power in the rural south during the First World War, Chapel Hill 2004: University of North Carolina Press.

- Kennedy, David M.: Over here. The First World War and American society, New York 1980: Oxford University Press.

- Kennedy, Ross A.: The will to believe. Woodrow Wilson, World War I, and America's strategy for peace and security, Kent 2009: Kent State University Press.

- Knock, Thomas J.: To end all wars. Woodrow Wilson and the quest for a new world order, New York 1992: Oxford University Press.

- Lengel, Edward G.: To conquer hell. The Meuse-Argonne, 1918. The epic battle that ended the First World War, New York 2009: Henry Holt and Co.

- Smythe, Donald: Pershing, general of the armies, Bloomington 1986: Indiana University Press.

- Sterba, Christopher M.: Good Americans. Italian and Jewish immigrants during the First World War, Oxford 2003: Oxford University Press.

- Trask, David F.: The AEF and coalition warmaking, 1917-1918, Lawrence 1993: University Press of Kansas.

- Trout, Steven: On the battlefield of memory. The First World War and American remembrance, 1919-1941, Tuscaloosa 2010: University of Alabama Press.

- Whalan, Mark: The Great War and the culture of the new negro, Gainesville 2008: University Press of Florida.

- Williams, Chad Louis: Torchbearers of democracy. African American soldiers in the World War I era, Chapel Hill 2010: University of North Carolina Press.

- Zeiger, Susan: In Uncle Sam's service. Women workers with the American Expeditionary Force, 1917-1919, Ithaca 1999: Cornell University Press.

- Zieger, Robert H.: America's Great War. World War I and the American experience, Lanham 2000: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.