Lusitania’s History and Prelude↑

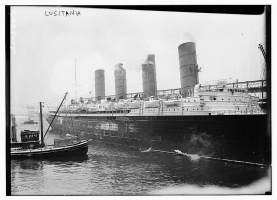

Commissioned by the Cunard Line, the RMS Lusitania was designed by Leonard Peskett (1861-1924) and built by John Brown and Company. It was fitted for service on 26 August 1907. During its eight years in service, the Lusitania made 202 transatlantic crossings on its infamous Liverpool-New York route. Her construction and operation were subsidized by the British government, which allowed the British War Office to commandeer the ship as an Armed Merchant Cruiser after the declaration of war in 1914. The government added a hidden compartment below deck that was used to carry war supplies across the Atlantic Ocean.

Prior to spring 1915, the German military engaged in restricted submarine warfare, meaning that submarines endeavored to engage only naval ships. In February 1915, Germany declared the seas around the British Isles a war zone and warned that both merchant and neutral ships entered this area at their own risk. On 18 February 1915, Germany instituted a policy of unrestricted submarine warfare. All ships were now fair game within the designated war zones.

In the days leading up to the Lusitania sinking, Germany repeatedly warned American citizens not to sail on British ships in the war zone. They justified their decision to attack passenger and merchant ships by noting the British policy of transporting war munitions across the Atlantic on merchant vessels. The Imperial German Embassy even issued a warning by placing an advertisement in fifty different American newspapers.

The Voyage↑

On its final voyage, William Thomas Turner (1856-1933) captained the ill-fated Lusitania. The liner encountered a U-20 submarine off the coast of Ireland at 2:10 pm on 7 May 1915. The captain of the U-boat, Walter Schweiger (1885-1917), gave the order to fire one torpedo, which struck the Lusitania near its bow. The ship began to founder as the lower compartments filled with water before a second powerful explosion rocked the ship, causing it to sink in under twenty minutes. Investigations concluded that the second blast described by many of the survivors was either from munitions stored below deck or from a coal-dust explosion. The attack killed 1,198 people, including 128 Americans. The inability of the passengers and the crew to set up the collapsible lifeboats before the ship sank caused many to drown or die of hypothermia.

Aftermath↑

On 8 May 1915, the German government issued a statement saying that the Lusitania had been carrying war supplies, as shown on the ship’s cargo manifesto, which had been published in the New York Times prior to 1 May. According to the German government, the Lusitania was a legitimate military target. The Lusitania’s cargo included 4,200,000 rounds of rifle cartridges, 1,250 empty shell cases, and eighteen cases of non-explosive fuses. Woodrow Wilson (1856-1924) did not want the American government to overreact to the situation. He chose to correspond extensively with the German government. Wilson insisted that Germany apologize and compensate the American victims and their families, steps the Germans initially refused to take, preferring to shift the blame to the British. While Germany and the United States navigated these diplomatic tensions, the sinking offered fodder for the British propaganda effort within the United States.

In the days and months that followed, the British churned out poster after poster using the Lusitania as a reason for individuals to aid the British war effort. The British published posters showing the sinking with the words “Lest We Forget” or “Irishmen: Avenge the Lusitania, Join an Irish Regiment To-day.” The British press also published numerous accounts of “circling U-boats” and “gloating U-boatmen” at the site, as well as tales of the German machine-gunners firing on passengers in the water, all of which were fabricated.[1] British and American sentiments were further outraged after the news appeared that a German metalworker in Munich had cast one hundred medals celebrating the sinking of the Lusitania. In reality, the medallion satirized the British willingness to put women and children in danger by letting them sail on ships carrying munitions. The British, however, later created their own version of the German commemoration medal and distributed thousands throughout the United States.

The disaster also gave rise to the first American propaganda poster of the war in support of the preparedness movement, a recruitment poster that showed a woman and baby drowning with the title, “Enlist,” emboldened across the top.

Assigning Fault↑

Following the tragedy, the British, American, and German governments sought to place blame for the sinking. Cunard Line first came under attack because the company had promised that the ship would be protected by British destroyers during its crossing; however, no such protection was given. The British government stated that it had not given the Lusitania an escort because the government believed that the ship’s speed did not warrant the extra protection. The British Admiralty also employed various schemes to shift blame away from the British government. It used Captain Turner as a scapegoat, saying that he ignored orders to carry out zigzagging measures to outmaneuver submarines, that he chose not to take a mid-channel course across the Atlantic, and that he reduced speed in the war zone.

Germany remained steadfast in asserting that the sinking of the British luxury liner was justified. They argued that the ship was classified as an armed merchant cruiser, had run under neutral colors, had been ordered by the British government to ram enemy submarines, and was carrying allied ammunitions and possibly Canadian troops. Germany accused Britain of using civilians as a shield in wartime.

In 1918, with the United States now at war against Germany, American survivors and families of the victims submitted civil lawsuits against Cunard Lines and Captain Turner. The American judge, Julius M. Mayer (1865-1925), absolved both Cunard and Captain Turner of all blame, stating that the blame lay firmly with the German government. The victims were told to petition the German government for monetary damages, which Germany paid by 1925.

Influence on US Entry↑

The sinking of the Lusitania created a momentary crisis in German-American relations. This diplomatic impasse ended with Germany’s agreement to respect the rights of neutral nations, which allowed for an improvement in diplomatic relations until January 1917, when Germany announced that it was reestablishing the policy of unrestricted submarine warfare. This announcement, along with the discovery of the Zimmermann Telegram in April 1917, influenced the United States Congress to declare war on the Central Powers and thus to enter the war on the side of the British.

Chelsea Medlock, Oklahoma State University

Section Editor: Lon Strauss

Notes

- ↑ Preston, Diana: Lusitania. An Epic Tragedy, New York 2002, p. 309.

Selected Bibliography

- Bailey, Thomas Andrew / Ryan, Paul B.: The Lusitania disaster. An episode in modern warfare and diplomacy, New York 1975: Free Press.

- Ballard, Robert D. / Dunmore, Spencer: Exploring the Lusitania. Probing the mysteries of the sinking that changed history, New York 1995: Warner Books.

- Gray, Edwyn: The U-boat war, 1914-1918, London 1994: L. Cooper.

- Preston, Diana: Lusitania. An epic tragedy, New York 2002: Walker & Co.

- Tucker, Robert W.: Woodrow Wilson and the Great War. Reconsidering America's neutrality, 1914-1917, Charlottesville 2007: University of Virginia Press.