Introduction: The Film Industry in United States in 1914↑

When the Great War erupted in Europe in August 1914, it disrupted a dynamic, international film industry. Pathé Frères, a major French producer-distributor, had first sold, then rented its films to exhibitors from offices in London, Berlin, Moscow, Vienna, Milan, St. Petersburg, Odessa, and New York, in addition to 33 other cities. Italy and Denmark supported vibrant national cinemas. American films were already being exported to Europe by 1909.[1] Just as the war upset international trade, it also altered the balance of power among competing film companies. One long-lasting consequence of World War I was that the United States film industry would emerge victorious from the commercial fray. It exerted stylistic influence and saturated movie screens around the world for the remainder of the 20th century.

From 1914 until the United States entered the war on 6 April 1917, the American film industry benefitted from America’s status as a non-combatant nation. Unimpeded by foreign competition, its production, distribution, and exhibition branches continued to develop along lines already established. By 1917, the footings of its oligopolistic business structure were set and most American films conformed to conventions of narrative and style that later would be called Classical Hollywood Cinema.[2] A film star system developed in tandem as certain actors stood out, distinguished by their appearance, personae, life styles, and the adulation of movie-goers. These two systems functioned symbiotically: the traits of stars and the fictional characters they portrayed became enmeshed. This relationship affected screenwriting as well as film advertising and promotion and it functioned to mediate a plethora of complex relationships between the motion picture industry and its consumers. Thus, when the motion picture industry had to confront challenges posed by working within a nation at war, its infrastructure was ready and willing to aid the government; it was also abundantly able to protect its commercial interests. The principle of practical patriotism, that it was appropriate and reasonable to combine allegiance to country and to business, undergirded the American film industry’s behavior during World War I.

Wartime Mobilization through the Film Industry: Aiding the Government’s Propaganda Campaign↑

According to President Woodrow Wilson (1856-1924): “The film has come to rank as a very high medium for the dissemination of public intelligence and since it speaks a universal language it lends itself importantly to the presentation of America’s plans and purposes.”[3] As early as 23 May 1917, the film industry’s main trade organization, the National Association of the Motion Picture Industry (NAMPI), offered the support of its member companies—among the strongest in the industry—to help the government fight the war on the home front. Under the aegis of NAMPI, the film industry mobilized its members—leading companies including Universal, Bell and Howell; Moving Picture World; and individuals such as Adolph Zukor (1873-1976) and D.W. Griffith (1875-1948), to “enlist.” As American participation in the war ramped up, NAMPI assigned members to work with the United States Food Administration, the War Department, the United States Civil Service Commission, the United States Department of Labor, the Department of Agriculture, and the Commission on Training Camp Activities.[4]

Early in the war, the film industry, via NAMPI, lent its significant resources to aid the launch of the government’s first Liberty Loan campaign in response to a request made by William Gibbs McAdoo (1863-1941), the secretary of the treasury.[5] For the fund-raising effort, 30,000 lantern slides printed with promotional slogans developed by the Liberty Loan Publicity Committee were distributed to movie theaters. In addition, 8,000 copies of a short film showing President Wilson’s “historic message to the American People to do their duty” by buying liberty bonds were also exhibited on the nation’s screens. In 1918, for the Third and Fourth Liberty Loans, the industry’s brightest stars, including Mary Pickford (1892-1979), Douglas Fairbanks (1883-1939), and Charlie Chaplin (1889-1977) starred in short films, 100% American, Sic ‘Em Sam, and The Bond, which promoted patriotic investments. These stars and others like Marguerite Clark (1883-1940), William S. Hart (1864-1946), and Marie Dressler (1868-1934) also attended rallies where they exhorted huge crowds to “Lend the Way They Fight.” The industry urged its own members to lead by example and buy bonds too.

NAMPI’s membership grew in 1917 and 1918. While the desire to do their bit surely motivated the actions of NAMPI’s members, they were also worried that the film industry might be deemed “nonessential” in a nation at war. NAMPI’s effective distribution of propaganda aided the government and the actions of the organization’s member companies burnished the film industry’s public image. The film industry’s cooperative attitude helped the NAMPI defeat most state and all federal attempts to censor its films.

War Time Mobilization through the Film Industry: The Films of World War I↑

In the first months after the United States entered the war, the motion picture trade press debated what sort of movies American audiences wanted to watch. Did they desire stories to help them escape from the fearful present or should films show contemporary reality? Practical patriotism and a three-to-sixth-month long production process help to explain the fact that over the eighteen months of American involvement in WWI, about 80 percent of the films made and screened in theaters large and small, in both cities and towns, made no reference to the conflict. Instead, westerns, melodramas, and comedies among other generic types entertained movie-goers. Nevertheless, there was a slow, steady increase in production of war-related films as the real war raged abroad. “Hate-the-Hun” films (“Hun” being the derogatory term used for the German enemy) were released relatively late in the war: The Kaiser, The Beast of Berlin (March 1918), To Hell with the Kaiser (June 1918), and The Prussian Cur and Kultur (September 1918). Accounting for the fact that a film might take weeks or months to open in the Midwest after its New York premier, the number of virulent anti-German movies that played in Stevens Point, Wisconsin, for instance, was significantly less than on the east coast. In other words, over the course of World War I, Americans who went to the movies watched the sorts of narrative feature films they were accustomed to seeing—most with no narrative or documentary relationship to the war. War-related film programming never flooded onto American screens.[6]

Still, numbers do not tell the full story about American films made during World War I. It was significant that some of the era’s biggest stars including Mary Pickford (The Little American, July 1917) and Charlie Chaplin (Shoulder Arms, 1918) did appear in war-related feature films. D. W. Griffith also contributed a prestige picture, the road show Hearts of the World (March 1918). This film was, arguably, one of the most popular films made during this time. It played for months in New York City and even in Milwaukee, Wisconsin it ran for an unprecedented six weeks at the Davidson Theatre, a venue that usually presented plays.

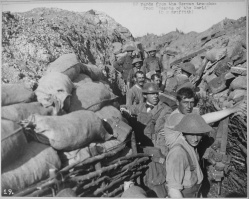

The war-related films produced while America fought in the Great War contributed to establishing the iconic image of battle during WWI: the muddy trench, a barren no-man’s land denuded of all but skeletal trees and barbed wire. The German characters in these movies were stereotypes, reiterating representations found in the propaganda posters of the time. They drank wine from broken-necked bottles and destroyed art; they threw babies out of windows; they executed children and old people. Significantly, in the narrative of many WWI-era war films, the plot built to the point where a bestial German attempted to rape the white heroine, and then was saved by a white American man, a racialized trope established most influentially by D.W. Griffith’s film about the American Civil War and Reconstruction era, Birth of a Nation, in 1915. Women played a central role in these war-related stories set mainly in Europe. This would change in the war-related films of the 1920s and 1930s, which most often focused on the life of the soldier and foregrounded combat on the ground, and as time passed, in the air. Especially in the 1920s, verisimilitude was the key selling point for war-related films including The Big Parade (1925), What Price Glory? (1926), and Wings (1927). Women became relegated to the subplot and kept, most often, on the home front.

The United States Government as Film Producer↑

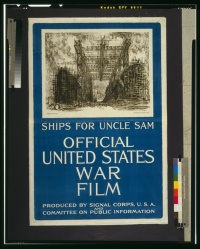

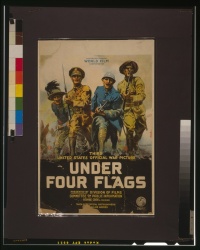

Early in war, President Woodrow Wilson created the Committee on Public Information (CPI). Its head, George Creel (1876-1953), saw his mission as a “vast enterprise in salesmanship, the world’s greatest adventure in advertising.”[7] Among its many departments whose goals included informing and mobilizing the home front was the Division of Films. Using footage shot by the Army Signal Corps, the Division produced a newsreel called The Official War Review, which was shown in about half of the movie theaters in the U.S. In addition, the Division produced feature length documentaries: Pershing’s Crusaders (May 1918), America’s Answer (August 1918), and Under Four Flags (November 1918). These films also were widely screened and the CPI promoted them as patriotic civic events.[8]

Film Exhibitors Enlist on the Home Front↑

U.S. film exhibitors managing some 1,750 theaters, followed the dictates of NAMPI and advice promulgated by motion picture trade journals including Moving Picture World and Exhibitor’s Trade Review. They also acted in concert with local business colleagues in cities and towns throughout the United States. As it had for film producers, practical patriotism also guided exhibitors’ commercial responses to the war. In fact, the phrase “practical patriotism” comes from an advertisement placed by a New York theater manager. He urged patrons to come and see The Bar Sinister, a melodrama with racist themes whose plot centered upon kidnapping not war, because the purchase of a ticket also entered them into the theater’s sweepstakes to win a fifty-dollar Liberty Bond. This strategy gave the manager a new selling point and simultaneously helped to cultivate good will among his patrons by his patriotic action. The government, meanwhile, benefited from free advertising for its Bond sales and its coffers were increased by fifty dollars.[9]

During 1917 and 1918, film exhibitors turned newly minted, potentially harmful, government regulations to their advantage. In the fall of 1917, the federal government instituted a tax on theater admissions. Exhibitors passed the cost on to their consumers explaining it as another way that the ticket buyer was helping the government to finance the war. “Remember This Tax Goes to U.S. Government. Every Penny Spent Helps Load a Rifle in France. DO YOUR BIT.”[10] In addition, in the harsh winter of 1918, the government imposed national measures to conserve fuel. Manufacturers and businesses east of the Mississippi River, including Minnesota and Louisiana, were ordered to close for ten consecutive Mondays starting at midnight on 19 January. This would have affected movie theaters. Almost immediately however, U.S. Fuel Administrator Harry A. Garfield (1863-1942) amended the order to allow motion picture theaters to switch their closing day to Tuesday effectively providing them with a three-day weekend. Managers also enhanced the prestige and respectability of their theaters by lending space for civic appeals. They advertised and hosted benefits for war-related causes including the Red Cross and war bond drives. They served as collection points for peach pits that were processed and used as part of the filtering process in gas masks.

The Four Minute Men provided the most salient example of how film exhibitors protected and promoted their business interests while they also participated in the war effort and garnered kudos from their communities. The Four Minute Men included prominent local citizens in cities and towns throughout the United States: bankers, professors, lawyers, businessmen, and clergy among others who were also deemed to be effective public speakers. Under the auspices of the CPI and using talking points prepared in Washington, D.C., members gave short speeches of four minutes duration at movie theaters – purportedly the length of time it took to change reels. The aim was to present short informative and persuasive speeches on topics including, “The Liberty Loan, 23 May-15 June,” “Why We Are Fighting, 23 July-5 August,” and “The Food Pledge Campaign, 29 October-4 November.” In the days before radios and televisions in American homes, the Four Minute Men provided messages, scripted by the federal government, on the same topic during the same time span in a place where people from all demographic groups gathered—movie theaters. The Four Minute Men were, “America’s nation-wide hook-up…united under CPI leadership for coordinated and synchronized expression of Wilsonian doctrine.”[11] Cooperating with this organization also allowed theater managers to control access to their stages during World War I. Too many people wanting to speak to the audience would have been a disruption to the business of showing movies.

Drawing Lessons from World War I in Film↑

The speed and smoothness with which the U.S. film industry and government began collaborating to mobilize the home front in the spring of 1917 is a persuasive demonstration that each institution appreciated the utility of the other. The government could deploy propaganda through many channels including films themselves, but movie theaters also to help spread its requests for food conservation, support for Liberty Bonds, and recruitment. The film industry, operating from a more defensive posture, understood that government posed a threat to its business as usual and its potential for expansion. The foundation for both positions rested on the fact that by 1917 movies mattered—to business folk, to audiences and to opinion-makers. The film industry was profitable; and via its narratives, style, and stars, it was broadly influential. The relationship between the government and the film industry in World War I would serve as the successful precedent for future interactions.

A principal lesson to be learned from studying the behavior of the American film industry and its production, distribution and exhibition of films during the war is that none of its actions occurred in a vacuum. The industry developed in line with a general business trend in the United States toward consolidation; film narrative and style evolved according to tenets of classical Hollywood cinema, in place by 1917; and the business of theater management continued to conform to dictates from motion picture trade journals that advocated stitching the picture house into the fabric of the community.[12] The war, before and after U.S. entry, did not change these trajectories, although it surely gave exhibitors added momentum to join with the business people in their towns and cities.

A lesson learned from studying the films made during World War I, for example: The Little American (1917), Hearts of the World (1918), or Shoulder Arms (1918) and those war films produced in the 1920s, especially The Big Parade (1925) and Wings (1927), and through the decades, is that the narrative motifs which typify the World War I war film changed. In other words, the World War I war film provides an exemplar for how film genres alter over time. Forces including technology (recorded sound, wide screen projection); changing public knowledge, understanding, and opinion regarding the war; and the mode of production in the Hollywood (the studio system, among others), influenced such shifts.

Still, what remains constant is the iconography of the war on film. The mise-en-scène of films that tell stories about World War I signifies the bleak failure of this war to end all wars. Sand-bagged and muddy trenches are gashes in a flat landscape punctuated by stick-like trees. Soldiers go “over the top” and into a no-man’s-land where they run a gauntlet of barbed wire coiled on stumpy criss-crossed timbers. In the midst of battle the image is softened by the smoke of exploding bombs. As recently as Steven Spielberg’s 2011 War Horse, these aspects of the setting abide. If the film includes the war in the air, there will be a dogfight, while below trenches scar the fields where tanks roll like giant beetles.

World War I and film also prompts historians to use conventional research tools and methods as well as to seek out new ones in the attempt to explain the function of film during wartime. It is important to understand how film production and distribution worked before claims can be made about the influence of particular films or for movies in general. This also argues for study of film exhibition and reception at the local level across the U.S. and comparative studies of production, distribution and exhibitions transnationally.[13]

Leslie Midkiff DeBauche, University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point

Section Editor: Edward G. Lengel

Notes

- ↑ For information about the French film industry, 1896-1914, see Abel, Richard: The Ciné Goes to Town, French Cinema 1996-1914, Berkeley 1994, especially chapter 1; Thompson, Kristin: Exporting Entertainment. America in the World Film Market 1907-1934, London 1985, p. 5, p. 38.

- ↑ For comprehensive history and analysis of the classical Hollywood system see Bordwell, David / Staiger, Janet / Thompson, Kristin: The Classical Hollywood Cinema, Film Style and Production to 1960, New York 1985.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 109.

- ↑ See especially Chapter 4, DeBauche, Leslie: Reel Patriotism. The Movies and World War I, Madison 1997.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 108. Collins, Sue: Film, Cultural Policy, and World War I Training Camps. Send Your Soldier to the Show with Smileage, in: Film History 26/1 (2014), pp. 1-49.

- ↑ I have found only a few instances of the U.S. government participating in the production of war-related films. One, notable example is The Unbeliever (1918). This film had the cooperation of the Marines and was used to help their recruitment efforts. The star of the film, Raymond McKee, was featured on a Marine Corps recruiting poster and in a short film called Fit to Win produced by the Commission on Training Camp Activities for the War Department which cautioned soldiers about venereal disease.

- ↑ Cited in Brewer, Susan: Why America Fights. Patriotism and War Propaganda from the Philippines to Iraq, New York 2009, p.56.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 64.

- ↑ DeBauche, Reel Patriotism 1997, p. 201.

- ↑ Advertisement for the Strand Theater, Stevens Point Daily Journal, 22 October 1917, p. 3.

- ↑ Mock, James R. / Larson, Cedric: Words That Won the War. The Story of the Committee on Public Information, Princeton 1939, p. 113.

- ↑ Sargent, Epes Winthrop: Picture Theater Advertising, New York 1915.

- ↑ Engelen, Leen / DeBauche, Leslie Midkiff / Hammond, Michael: Snapshots. Local Cinema Cultures in the Great War, in: Hammond, Michael (ed.): Historical Journal of Film, Radio, and Television 35/4 (2015), pp. 631-655.

Selected Bibliography

- Bordwell, David / Staiger, Janet / Thompson, Kristin: The classical Hollywood cinema. Film style and mode of production to 1960, London 1984: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Brewer, Susan A.: Why America fights. Patriotism and war propaganda from the Philippines to Iraq, Oxford et al. 2011: Oxford University Press.

- Brownlow, Kevin: The war, the west, and the wilderness, New York 1979: Random House.

- Castellan, Jaes W. / Dopperen, Ron van / Graham, Cooper C.: American cinematographers in the Great War, 1914-1918, Herts 2014: Libbey.

- Collins, Sue: Film, cultural policy, and World War I training camps. Send your soldier to the show with smileage, in: Film History 26/1, 2014, pp. 1-49.

- Dibbets, Karel / Hogenkamp, Bert (eds.): Film and the First World War, Amsterdam 1995: Amsterdam University Press.

- Engelen, Leen / Midkiff DeBauche, Leslie / Hammond, Michael: Snapshots. Local cinema cultures in the Great War, in: Historical Journal of Film, Radio, and Television 35/4, 2015, pp. 631-655

- Isenberg, Michael T.: War on film. The American cinema and World War I, 1914-1941, London 1981: Associated University Presses.

- Keil, Charlie / Singer, Ben (eds.): American cinema of the 1910s. Themes and variations, New Brunswick 2009: Rutgers University Press.

- Kelly, Andrew: Filming 'All Quiet on the Western Front'. Brutal cutting, stupid censors, bigoted politicos, London 1998: I. B. Tauris.

- Midkiff DeBauche, Leslie: Reel patriotism. The movies and World War I, Madison 1997: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Midkiff DeBauche, Leslie: Melodrama and the World War I war film, in: Quaresima, Leonardo / Raengo, Alessandra / Vichi, Laura (eds.): I Limiti della rappresentazione, Udine 2000: Forum, pp. 177-186.

- Paris, Michael (ed.): The First World War in popular cinema. 1914 to the present, Edinburgh 1999: Edinburgh University Press.

- Ritzenhoff, Karen A. / Tholas-Disset, Clémentine: Humor, entertainment and popular culture during World War I, New York; Basingstoke 2015: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Robinson, Cedric J.: Forgeries of memory and meaning. Blacks and the regimes of race in American theater and film before World War II, Chapel Hill 2012: University of North Carolina Press.

- Rollins, Peter C. / O'Connor, John E. (eds.): Hollywood's World War I motion picture images, Bowling Green 1997: Bowling Green State University Popular Press.

- Thompson, Kristin: Exporting entertainment. America in the world film market, 1907-1934, London 1985: British Film Institute.

- Usai, Paolo Cherchi (ed.): The Griffith project, volume 9, London 2005: British Film Institute.

- Williams, David: Media, memory, and the First World War, Montreal 2014: McGill-Queen's University Press.

- Wood, Richard E. / Culbert, David Holbrook: Film and propaganda in America. World War I. A documentary history, volume 1, New York 1990: Greenwood Publishing Group.