Introduction↑

In the years leading up to America’s entry into the First World War a debate raged within the United States over universal military training. The United States had a traditional aversion to maintaining a large peacetime army, with no tradition of peacetime conscription as was common in Germany and France. Hoping to reverse this trend, both civil and military advocates sought to sell American citizens on the idea of preparedness as essential to national security. Organizations such as the American Defense League, the Army League, and the National Security League formed to oppose President Woodrow Wilson’s (1856-1924) insistence that the National Guard was an adequate reserve force.[1]

The Preparedness Campaign↑

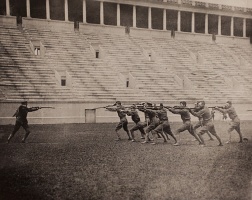

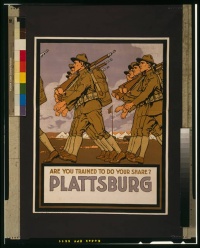

The first tangible attempt to better prepare American men for possible wartime service came in 1913 when U.S. Army Chief of Staff Major General Leonard Wood (1860-1927), a strong proponent of national defense, created two experimental military instruction camps for college students to attend during their summer vacations. One was in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, the other in Monterrey, California. Two years later the successful program expanded to four camps and continued to pick up steam when the Germans sank the Lusitania in May 1915. Now more than ever Americans recognized the possibility that the United States might be drawn into the Great War. In New York citizens sought and received government support to set up a military training camp that was modeled after the ones organized for college students. On 8 August 1915, the first camp was established in Plattsburg with 1,200 enrollees. Known as the “Plattsburgh Idea”, its success encouraged other states to follow suit and over the next two years civil-military camps were created throughout the country.[2] Hundreds of distinguished public and private leaders attended the camps, including the mayor of New York City, John Purroy Mitchel (1879-1918), as well as two of Theodore Roosevelt’s sons, Quentin Roosevelt (1897-1918) and Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (1887-1944). Julius Ochs Adler (1892-1955), general manager of the New York Times and nephew of Adolph Ochs (1858-1935), the newspaper's publisher, also attended. Adler's pro-national defense attitude would favorably influence the Times coverage of defense issues as the nation headed for war.

As the “Plattsburgh Idea” continued to grow, it spawned a professional organization, the Military Training Camp Association (MTCA). Led by New York attorney Grenville Clark (1882-1967), the MTCA coordinated many of the camps’ administrative duties and also lobbied Congress over military reform, especially universal military training.[3] In early 1917 when war with Germany seemed imminent the MTCA took responsibility for supplying officers to train and command the volunteer forces that it expected to fight the war. The MTCA and the War Department carried on a nationwide recruiting campaign, and by late August 1917, 341 candidates had graduated from the first series of training camps.[4]

The National Defense Act of 1916↑

A direct result of the preparedness movement was the National Defense Act of March 1916. Uncertain whether his diplomatic efforts would succeed in convincing the Germans to halt U-boat attacks against passenger and merchant ships, Wilson approached the question of military preparedness cautiously. The escalating diplomatic exchanges between Wilson and the German government influenced the preparedness debate by alerting Americans that war between the two countries was now a real possibility. Wilson's Secretary of War, Lindley M. Garrison (1864-1932), made preparedness a top priority. He had outlined his ideas in a report on readiness: Statement of a Proper Military Policy for the United States (1915).[5] The Secretary wanted to more than double the Regular Army, increase federal support for the National Guard, and create a new 4 million-man volunteer force to be called the Continental Army. He also wanted a trained reserve run by the federal government as opposed to state control of the Guard.[6]

Wilson would only accept a small increase in the Regular Army, but favored the idea of a Continental Army. Garrison's proposal received support in the Senate, but strong proponents of the National Guard resisted it in the House of Representatives. Influential congressmen countered with a bill requiring increased federal responsibility for the Guard, acceptance of federal standards, and agreement by the Guard to respond to a presidential call to service. Under pressure from these congressmen, Wilson rejected Garrison’s proposals and instead supported the Congressional plan. This, among other issues, prompted Garrison to resign. He was replaced by Newton D. Baker (1871-1937), who opposed preparedness. Baker opposed war in general and served as a spokesman for one of the largest pacifist organizations, the “League to Enforce Peace.”[7]

Among its provisions, the National Defense Act of 1916 granted power to the president to place orders for defense materials and to force industry to comply. The act further directed the Secretary of War to conduct a survey of all ordnance and munitions industries. Overall the National Defense Act of 1916 was a weaker version of Garrison’s preparedness proposal, but it did help to strengthen and modernize American armed forces. Furthermore, the new law granted the federal government emergency wartime powers over industry and transportation for the first time. The president now had the authority to compel any business to give priority to orders for goods from the government if the nation went to war.[8]

The administration furthered the preparedness program by creating a U.S. Shipping Board to regulate sea transport and developing a naval auxiliary fleet and a merchant marine. Fearing a concentration of power in the hands of the Regular Army, the law curtailed the creation of a powerful General Staff by sharply limiting the number of officers who could be detailed to serve on the staff at the same time in or near Washington, D.C. The bill nevertheless represented the most comprehensive military legislation enacted by the U.S. Congress to date.

Preparations for War↑

The National Defense Act of 1916 affected the size and organization of America’s peacetime military. It authorized an increase in the peacetime strength of the Regular Army over a period of five years to 175,000 men and wartime strength of close to 300,000. Bolstered by federal funds and federally stipulated organization and standards of training, the National Guard was also gradually increased in size and obligated to respond to the call of the president.[9] The Wilson administration also strengthened the U.S. Navy during this period with the passage of the Naval Act of 1916. It provided for the construction of ten battleships, sixteen cruisers, fifty destroyers, seventy-two submarines, and fourteen auxiliaries. The National Defense Act also allowed President Wilson to establish the Council of National Defense (CND) on 24 August 1916. It consisted of the Secretaries of War, Navy, Labor, Agriculture, Interior and Commerce. The Council’s responsibility was to investigate and advise the president and heads of executive departments on the strategic placement of industrial goods and services for potential and future use in times of war. In October 1916, Wilson appointed a non-partisan advisory commission, made up of business and industry leaders such as the presidents of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, the American Federation of Labor and Sears and Roebuck. The CND set up a network of 184,000 local defense councils throughout the United States, as well as a women’s committee to direct the work of around 4 million women. Despite there organisational efforts the CND had little real authority. It had no control over the country’s budget and had no authority to direct the American economy in times of war.[10]

On the heels of this legislative victory for the preparedness movement, a number of prominent individuals put their weight behind preparedness. Publisher Ralph Pulitzer (1879-1939) established a $100,000 prize for an annual transcontinental air race after visiting the Western Front and witnessing the importance of the air service for national defense. The National Academy of Sciences established the National Research Council to coordinate research during wartime. Inventor Thomas Edison (1847-1931) announced the need to train scientists to develop military art through laboratory research. Edison was then invited by Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels (1862-1948) to found the Naval Consulting Board.[11]

Intervention in Mexico↑

Meanwhile, political instability in Mexico had led to a revolution in 1910 and created tension between the United States and its southern neighbor. Beginning in 1911, Mexico became a continual testing ground for U.S. military preparedness. In April of that year President William H. Taft (1857-1930) sent about 16,000 troops to Texas for "war games" for four months. Although officially sent to the border for training exercises, unofficially American troops prepared for a possible incursion into Mexico. Three years later, in April 1914, four American sailors were arrested in the Mexican port city of Tampico in protest against President Wilson’s failure to recognize the country’s new president, General Victoriano Huerta (1850-1916). Although the sailors were quickly released, the American government insisted upon a public apology by Huerta. The Mexican president refused and Wilson ordered an occupation of Tampico and the seizure of another port city, Veracruz. By the end of April nearly 8,000 American soldiers and Marines under Maj. Gen. Frederick Funston (1865-1917) occupied Veracruz. It appeared that the two countries were headed toward war, but both Wilson and Huerta accepted mediation that resulted in the Mexican leader resigning from office.[12]

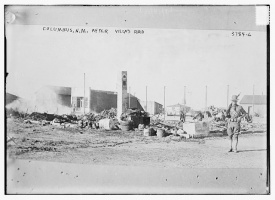

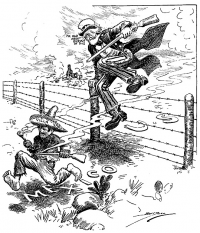

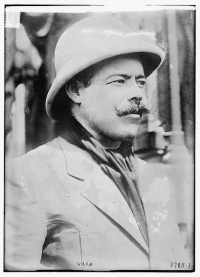

Then on 9 March 1916, Mexican revolutionary leader Francisco “Pancho” Villa (1878-1923) and between 500 and 1,000 men raided Columbus, New Mexico, killing a substantial number of American soldiers and civilians. Both public outcry and pressure from the army moved President Wilson to order the military to pursue Villa and punish him. The War Department was uncertain of how to react. During the past three years the General Staff had focused its planning on a full-scale war, and there was no contingency for pursuing a single guerrilla. Major General Hugh Scott (1853-1934), Chief of Staff of the Army, selected Brigadier General John J. Pershing (1860-1948) to lead a punitive expedition. On March 15, 1916, Pershing and 6,675 Regular Army troops entered Mexico in pursuit of Villa.

For the next several months Pershing’s troops chased Villa through unfriendly Mexican territory without catching him, but successfully dispersed most of his followers. Carranza soon grew tired of American troops in Mexico and insisted they withdraw. Wilson refused, but without cooperation from the Mexican government Pershing’s expeditionary force had little hope of catching Villa and his followers. Still, Pershing kept up his pursuit and there were occasional skirmishes between his forces and Mexican troops, the most notable of which occurred at Carrizal in June 1916 and resulted in significant casualties on both sides.

Wilson recognized the increasing threat of war with Mexico and called up 75,000 National Guard from all over America to join units from Texas, Arizona, and New Mexico already serving on the border. These troops were to act as a deterrent to further raids into the United States by Mexican bandits. Because of animosity toward state units by Regular Army officers and the War Department General Staff, none of the National Guard troops would cross the border into Mexico, but were instead used as a show of force.

By early February 1917 the Punitive Expedition was back on American soil. Despite its failure to capture Pancho Villa, the Mexican Punitive Expedition was by no means a wasted effort. Villa’s band was dispersed, which ended any serious threats on the border. From a military standpoint the most important result of the Punitive Expedition was the training received by the Regular Army in Mexico and the National Guard troops who served on the border. Additionally, the partial mobilization of National Guard forces demonstrated that they were needed to supplement the Regular Army during national emergencies. The Punitive Expedition also increased concerns among Regular Army officers that National Guard troops would require months of training before they could fight effectively in Europe.[13]

Conclusion↑

When the First World War commenced in August 1914, the United States had little reason to be concerned about the conflict. Yet when the conflict entered its second year, there was a major reconsideration of American military policy. In 1916 the Preparedness Movement successfully lobbied Congress to pass legislation that would bolster the size, organization, and financing of the nation’s naval and land forces.

The National Defense Act of 1916, however, still left the United States unprepared to send a fighting force to Europe when Congress approved President Wilson’s declaration of war on 6 April 1917.[14] The U.S. Army had about 127,000 officers and men in the Regular Army; there were an additional 80,000 federalized National Guard officers and men on the Mexican border, while 100,000 Guardsmen remained under state control. The U.S. Navy reported 4,300 commissioned and warrant officers commanding 60,000 men, while the Marine Corps strength stood at 511 officers and a little over 13,000 men.[15] Of the total U.S. Armed Forces in spring 1917, only a fraction of military personnel had served on foreign soil. This was not true for General Pershing, who had already seen extensive overseas combat during his career and was well versed in dealing with allied commanders. He was ultimately the best person to lead the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF). Unfortunately, there were not many generals like him and the United States would pay a price for its inexperience with large numbers of casualties.

Mitchell Yockelson, National Archives and Records Administration

Section Editor: Edward G. Lengel

Notes

- ↑ Finnegan, John Patrick: Against the Specter of a Dragon. The Campaign for American Military Preparedness, 1914-1917, Westport 1974, pp. 96-97.

- ↑ Coffman, Edward M.: The War to End All Wars. The American Military Experience in World War I, New York 1968, pp. 14-17.

- ↑ Finnegan, Against the Specter of a Dragon 1974, p. 70.

- ↑ Ibid, p. 71.

- ↑ Maslowski Peter/Millett, Allen: For the Common Defense. A Military History of the United States, York 1984, p. 323.

- ↑ Shrader, Charles Reginald (ed.): Reference Guide to United States Military History. 1865-1919, New York 1993.

- ↑ Finnegan, Against the Specter of a Dragon 1974, p. 97.

- ↑ Ibid, pp. 155-157.

- ↑ Matloff, Maurice: General Editor, American Military History, Washington 1969, p. 367.

- ↑ Finnegan, Against the Specter of a Dragon 1974, p. 161.

- ↑ Shrader, Reference Guide 1993, p. 109.

- ↑ Ibid, pp. 287-289.

- ↑ Shrader, Reference Guide 1993, pp. 260-262.

- ↑ Finnegan, Against the Specter of a Dragon 1974, pp. 194-195.

- ↑ Shrader, Reference Guide 1993, p. 110.

Selected Bibliography

- Coffman, Edward M.: The war to end all wars. The American military experience in World War I, Lexington 1998: University Press of Kentucky.

- Ferrell, Robert H.: Woodrow Wilson and World War I, 1917-1921, New York 1985: Harper & Row.

- Finnegan, John Patrick: Against the specter of a dragon. The campaign for American military preparedness, 1914-1917, Westport 1974: Greenwood Press.

- Harries, Meirion / Harries, Susie: The last days of innocence. America at war, 1917-1918, New York 1997: Random House.

- Matloff, Maurice (ed.): American military history, Washington, D.C. 1969: Office of the Chief of Military History, U.S. Army.

- McCallum, Jack Edward: Leonard Wood. Rough rider, surgeon, architect of American imperialism, New York 2006: New York University Press.

- Millett, Allan Reed / Maslowski, Peter: For the common defense. A military history of the United States of America, New York; London 1984: Free Press; Collier Macmillan.

- Shrader, Charles R.: Reference guide to United States military history, 1865-1919, New York 1993: Facts on File.

- Tucker, Robert W.: Woodrow Wilson and the Great War. Reconsidering America's neutrality, 1914-1917, Charlottesville 2007: University of Virginia Press.