Organization↑

When the United States entered World War I, the miniscule Regular Army of 127,000 officers and soldiers lacked such essentials as a general staff, division structure, and modern weapons. Despite these shortcomings, President Woodrow Wilson (1856-1924) ordered newly promoted General John J. Pershing (1860-1948) to organize the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) in France sufficient to conduct combat operations on par with the Allied armies. President Wilson believed that only a major, independent American contribution to the war effort would earn him sufficient political capital to lead the eventual peace negotiations.

To meet Wilson’s ambitious goal, the US had to fully mobilize its available manpower. Rejecting calls to organize volunteer units, Secretary of War Newton D. Baker (1871-1937) worked with Congress to enact a manpower draft sufficient for 100 combat divisions. In line with his strategic goals, Wilson rebuffed demands to amalgamate American troops in Allied units, and ordered Pershing to maintain “a separate and distinct component of the combined forces, the identity of which must be preserved”[1] With those orders, Pershing and a hand-picked staff of Regular officers sailed for France on 28 May 1917. After extensive study, Pershing decided to base the AEF in the Lorraine region, as it offered sufficient space for American lines of communication, as well as close proximity to the major strategic objective of Metz, Germany.

Doctrine and Training↑

The US army entered the war with an obsolete offensive doctrine, infantry employing marksmanship and bayonet attacks into the depth of the enemy defenses, with artillery and supporting arms relegated to ancillary roles. Observer reports from France highlighting the primacy of artillery and machine guns in defense preparation made little impression on Pershing, who insisted on preparing his divisions for “open warfare.” As the American army was critically short of experienced officers and non-commissioned officers (NCOs), contingents of veteran Allied officers were dispatched to the United States as trainers and advisors. Despite Pershing’s efforts to the contrary, junior American leaders learned from their Allied mentors how to organize set-piece, limited objective attacks supported with detailed fire plans.

With input from War Department planners, the Americans organized 28,000 man “square” divisions with four oversized infantry regiments, a design presumed to have greater staying power in combat than a three regiment German division. In practice, the square divisions were powerful in the defensive, but difficult to maneuver in offensive operations. The 1st Division was the first major American combat unit to arrive in France in June 1917. Despite its large cadre of Regulars, the division required extensive training before its infantry battalions were deemed ready to perform defensive front line duties in late October 1917. The hasty US mobilization meant every American division needed significant preparation under French or British tutelage before undergoing its baptism of fire in quiet sectors. After rejecting initial Allied demands for amalgamation, Pershing compromised on a plan in January 1918 to quickly ship six divisions to France to complete training and supervised front line duty under British tutelage. Later divisions were expected to complete their training in the United States. Ultimately, Pershing planned to assemble a powerful field army of 52 divisions in Lorraine, ready for a major role in the big push into Germany to end the war in 1919.

The First Major American Contributions↑

By March 1918, Pershing had four divisions near full combat readiness when Germany began its spring offensives intended to defeat the Allies before the Americans could tip the balance of power. Urgent Allied demands for replacement American riflemen and machine gunners compelled Pershing to soften his stance on amalgamation. First, Pershing agreed to temporarily attach the available divisions, along with the infantry regiments of the segregated African American 93rd Division to the French army. Shipment of replacement Riflemen and machine gunners from the United States were prioritized, with freshly arrived US divisions diverted to reinforce the hard-pressed British Expeditionary Force (BEF). By late May 1918, the US reinforcements had boosted the morale of the Allies, and played a role in successfully halting the German offensives. Of note was the first major US offensive operation by the 1st Division at Cantigny in May, and the strong performance of the US 2nd Division at Belleau Wood in June, and the 3rd Division at the Marne in July which helped halt the German drive towards Paris. Once the crisis ebbed, most of the US units returned to AEF control, except for the African American regiments loaned to the French, and two of the ten divisions attached to the BEF.

The Growing AEF↑

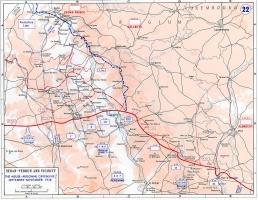

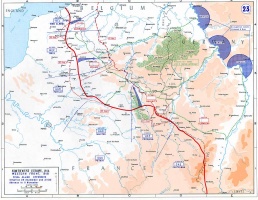

Encouraged by early American successes, Pershing activated the US First Army on 11 August 1918, thus fulfilling one of the major American war goals to create an independent field army. Faced with another demand to fragment the AEF by French Marshal Ferdinand Foch (1851-1929), Pershing responded by committing the AEF to sequential offensives; first, the reduction of the St. Mihiel salient, followed by the major Meuse-Argonne offensive. Supported by French and British artillery, tanks and aviation, the US First Army successfully cleared the St. Mihiel salient on 12-13 September 1918. Despite serious problems with clogged roads and bad weather, the First Army successfully regrouped a force of three corps controlling fourteen divisions, over 600,000 men, to take part in the Meuse-Argonne offensive on 26 September 1918. Unlike the St. Mihiel operation, the First US Army divisions soon became enmeshed in a grinding series of assaults against strong German defenses-in-depth.

Additionally, deficiencies in logistics administration, compounded by Pershing’s earlier decision to prioritize combat troops over logistics units, wreaked havoc on the Americans’ ability to fight in the Meuse-Argonne, shortfalls that had earlier prompted Secretary Baker to suggest the War Department assume control of the rear area services. Instead, Pershing transferred one of his best division commanders to reorganize the Service of Supply (SOS), while manpower shortages in the rear were temporarily solved by converting combat units into depot detachments.

The logistics crisis, War Department concerns, Allied criticism, and lack of progress in the fighting influenced Pershing’s decision to perform a major regrouping in mid-October 1918. While his battered divisions were rotated, and the logisticians given time to move supplies forward, Pershing relinquished command of the First Army to Lieutenant General Hunter Liggett (1857-1935), and activated a Second Army headquarters in a bid to improve command and control within the AEF. Under General Pershing’s strategic command, the AEF continued the Meuse-Argonne offensive until the Armistice.

Aftermath↑

From its modest beginnings, the AEF grew to a field army of 2 million men, of which some 1.4 million men saw active combat, and incurred 320,000 casualties while liberating more than two hundred miles of French territory. The entry of the AEF into the war boosted the morale of the hard-pressed Allies, and convinced many German leaders that military victory was no longer possible after the failed Spring Offensives of 1918. After the Armistice, Pershing designated the US Third Army, made mostly of Regular units, to occupy the Koblenz region of Germany, with priority given to demobilizing the draftee units as soon as possible. On 1 September 1919, the American Expeditionary Forces was officially deactivated with the departure of General Pershing and the last of his staff for the United States.

Harold Allen Skinner Jr., United States Army Reserve

Section Editor: Lon Strauss

Notes

- ↑ Palmer, Frederick: Newton D. Baker. America At War, volume I, New York 1931, p. 171.

Selected Bibliography

- Coffman, Edward M.: The war to end all wars. The American military experience in World War I, Lexington 1998: University Press of Kentucky.

- Faulkner, Richard Shawn: The school of hard knocks. Combat leadership in the American Expeditionary Forces, College Station 2012: Texas A & M University Press.

- Grotelueschen, Mark E.: The AEF way of war. The American army and combat in World War I, Cambridge; New York 2007: Cambridge University Press.

- Trask, David F.: The AEF and coalition warmaking, 1917-1918, Lawrence 1993: University Press of Kansas.

- U.S. Army Center of Military History (ed.): American armies and battlefields in Europe, Washington, D.C. 1992: U.S. Army Center of Military History.

- U.S. Army Center of Military History (ed.): United States Army in the World War, 1917-1919, Washington, D.C. 1988: U.S. Army Center of Military History.

- Woodward, David R.: The American army and the First World War, New York 2014: Cambridge University Press.