Introduction↑

World War I disrupted communal and familial monitoring mechanisms and reshaped urban – and, to a lesser degree, rural – sexual practices across Europe. The mass mobilization of troops increased the demand for prostitutes near military encampments. Recognizing that soldiers would have sex with prostitutes, some belligerent armies opened brothels near garrisons to limit the troops exposure to venereal disease (VD). In addition to the opening of brothels to serve the military, there was also an increase in clandestine prostitution, as some soldiers preferred to visit prostitutes outside of regulated brothels.

In 1914, many continental European countries practiced variations on the French regulatory system that sanitation engineer A.J.B. Parent-Duchâtelet (1790-1836) had developed in the early nineteenth century. The “French System” required that tolerated prostitutes register with the vice police and ply their trade in “closed” brothels. A key element of this system was the mandatory regular medical examination of prostitutes, which was meant to limit the spread of venereal disease among their clients. In contrast, Great Britain, its Dominions, and former colonies continued to prohibit prostitution during the war and forbade their troops to visit brothels on the fighting front.

Prostitution on the Home Front↑

Many home-front brothels served an increased number of clients following the war’s outset owing to the influx of men in arms preparing to go into the field. The concentration of soldiers also offered new opportunities for women to have clandestine sex with soldiers. Civilian and military authorities suspected these women of being infected with particularly virulent forms of VD because they were able to avoid the medical exams that were compulsory for registered prostitutes. Military leaders continued to advocate brothel-based prostitution, because they argued that medical examinations helped to limit the spread of VD.

Rates of clandestine prostitution in Great Britain increased dramatically between 1914 and 1918 because the war created more opportunities for illicit sex. “Khaki fever,” which refers to women and girls seeking soldiers and having illicit sex with them on the home front, concerned civilian leaders who desired tight control over women’s sexual behavior. The concern about women’s sexuality led to the creation of a Women Patrols Committee, an organization that attempted to prevent women and girls from having sex with soldiers. By limiting contact between women and soldiers, the Committee tried to prevent clandestine prostitution.

In the Habsburg Monarchy, owing to wartime economic privation, there was both an explosion of clandestine prostitution and the virtual collapse of regulated prostitution between 1914 and 1918. In addition to tolerated prostitutes, the vice police and the military focused on other women they believed practiced clandestine prostitution. Many of the suspects were young, often poor, unemployed, or working in low-wage positions. These women plied their trade on the streets, in bars, parks, pubs, nightclubs, and hotels of Austria-Hungary’s cities, ports, and garrison towns, and even some of its smaller municipalities.

Soldiers stationed in Belgium, France, and Germany visited brothels on the home front and near the fighting front. While many military officers turned a blind eye to enlisted men’s brothel visits, high rates of venereal disease sometimes led military officials to close those local brothels at which they believed that large numbers of soldiers became infected with VD. Soldiers continued to use prostitutes while on leave, despite superiors’ warnings about the incidence of venereal disease. Access to prophylaxes and crude treatments served to safeguard against the worst effects of VD.

Prostitution on the Fighting Front↑

The brothel industry boomed in wartime France owing to the large number of men stationed there. Both French and German military authorities opened brothels along the Western Front, giving soldiers access to prostitutes while at the front and on leave. In both countries, the military seized buildings, among them private homes and castles, for use as brothels. Different colored lanterns designated those for officers and those for enlisted men. Brothels were segregated based on military rank. Officers had access to more expensive prostitutes dedicated only to them. The prostitutes who serviced enlisted men would have made less money, worked longer hours, and seen more clients in a given time period than those intended for officers.

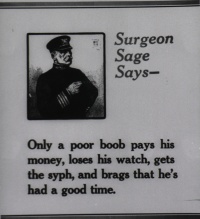

Although British and Dominion military authorities encouraged abstinence, officers provided medication and prophylaxis for soldiers who visited prostitutes. The US military also mandated abstinence. Officers realized that while US soldiers were barred from brothels, they would still go to them and therefore required VD exams for those believed to have had sex with prostitutes. Infected soldiers were treated and returned to the front as soon as they were ambulatory. Otherwise, visits to brothels were a non-issue in the US military, despite formal warnings.

In contrast to US and British directives, both the German and the Habsburg military authorities assumed that soldiers would visit prostitutes. Fearing that French prostitutes would deliberately infect their soldiers with VD, the German military relocated brothel prostitutes from Germany to purpose-built military brothels on the front. Military officials from the Central Powers also created brothels on the Eastern Front. The Habsburg military opened field brothels, including in occupied territory, that were organized by rank, as well as clinics to treat enlisted men for VD in an effort to limit its spread. When the Russians occupied Austrian territory in Western Galicia and Bukovina, their soldiers visited existing local brothels. Russian military officials demonstrated the same concerns about the deleterious implications of brothel-based and clandestine prostitution for their soldiers as had the Habsburg military before them.

Conclusion↑

Opposition to tolerated prostitution, which had been growing in many countries prior to 1914, continued during the war. After 1918, it resulted in the closing of brothels and the abolition of prostitution in some of the former belligerents. Russia abolished prostitution in July 1917, following the February Revolution, before withdrawing from the war. Reflecting increased influence of feminist and sex-reform organizations, Austria, Czechoslovakia, and Germany abolished regulation after the war. In contrast, Belgium, France, and Italy continued to tolerate prostitution throughout the interwar period.

Journey Steward, Northern Illinois University

Section Editor: Tamara Scheer

Selected Bibliography

- Harris, Victoria: Selling sex in the Reich. Prostitutes in German society, 1914-1945, Oxford; New York 2010: Oxford University Press.

- Herzog, Dagmar: Sexuality in Europe. A twentieth-century history, Cambridge; New York 2011: Cambridge University Press.

- Hirschfeld, Magnus: The sexual history of the world war, New York 1941: Cadillac.

- Le Naour, Jean-Yves: Le sexe et la guerre. Divergences Franco-Américaines pendant la Grande Guerre (1917-1918), in: Guerres Mondiales et Conflits Contemporains 197, 2000, pp. 103-116.

- Makepeace, Clare: Male heterosexuality and prostitution during the great war. British soldiers' encounters with Maisons Tolérées, in: Cultural and Social History 9/1, 2012, pp. 65-83.

- Röger, Maren; Debruyne, Emmanuel: From control to terror. German prostitution policies in eastern and western European territories during both world wars, in: Gender & History 28/3, 2016, pp. 687-708.

- Wingfield, Nancy M.: The enemy within. Regulating prostitution and controlling venereal disease in cisleithanian Austria during the Great War, in: Central European History 46/3, 2013, pp. 568-598.