Introduction↑

During the war, the importance of “Belgium” as an issue inspired heated discussions. In a 1928 monograph, the historian Henri Pirenne (1862-1935) presented the restoration of Belgium as the vindication of the liberal idea. Though no such synthesis was attempted in the next three-quarter century, the 1950s through the 1980s saw groundbreaking monographs. From the late 1990s, the renewal of First World War historiography touched on Belgium, leading to a more granular understanding of its war experience. Concomitantly, the neglect suffered hitherto by First World War archival collections in Belgium came to an end. All of this allows for a reasonably confident summing-up of what we know (and don’t know) about Belgium’s Great War, and how it sheds light on the war overall.

Belgium on the Eve of the War↑

In 1914, Belgium was the most densely populated state in the world, with as many inhabitants as Canada (7.6 million) on a small landmass.[1] Condensed and complex, it attracted considerable attention: the German historian Karl Lamprecht (1856-1915) called it a “microcosm of Europe”; the French sociologist Henri Charriaut (1873-?) called it a compressed “social laboratory” for the new century.[2] In the decades from 1894 to 1914, Belgium had become the world’s fourth commercial power. Antwerp, the continent’s most important port, was linked by rail to Central Europe. Belgium imported raw materials and exported (half-)finished products including railway rolling-stock. Belgian capital flowed to emerging economies. In 1908, Belgium had become a colonial power with the takeover of Leopold II, King of the Belgians’ (1835-1909) “Congo Free State,” a territory eighty times the size of the metropole, subjected to murderous depredation of human labour and natural resources. Belgian state rule over the Congo did away with this regime, while remaining essentially exploitative – and becoming increasingly lucrative, even if the systematic mining of mineral resources would only come into its own in the 1920s. Meanwhile, the metropole opened up to the world with vast infrastructure works (the new port of Zeebrugge, the canal harbor of Brussels), connected to what was at the time the world’s densest railway network, while a net of small-gauge lines allowed for widespread commuting, keeping even the largest cities mid-sized.

Belgium was also the fifth industrial power in the world; in 1913, half of the active population worked in manufacturing. What prosperity this generated was ill-distributed: the labour market was marred by low wages and long hours. Change was hampered by a “plural” franchise which allotted extra votes to educated and/or propertied men. A vast ten-day strike led by the Belgian Workers’ Party in April 1913 led to a promise of revision, which was interrupted by the outbreak of the war. Change was in the air over the linguistic question too. A slight majority of Belgians – 54 percent in 1910 - spoke predominantly or exclusively “Flemish” (Dutch) instead of French.[3] French remained the language of state affairs, continuing education, and social ambition generally. This led the champions of Flemish language rights – also known as the “Flemish Movement,” a constellation of interest groups rather than a formal party – to call for a Dutch-language-only university at Ghent which would uncouple social mobility from verfransing (“frenchification”).

Prosperous and open to the world, Belgium was in a vulnerable position as international tensions mounted. Acknowledging that neutrality alone would no longer suffice, Prime Minister and Minister of War Charles de Broqueville (1860-1940) launched a preparedness campaign which led to an August 1913 law imposing universal conscription. While it has long been assumed that Belgian society on the eve of the war was “unreservedly anti-militaristic,” in reality this law, and other militarizing measures, met with acceptance. This goes some way towards contextualizing Belgians’ reaction to the outbreak of the war.[4]

1914: Invasion↑

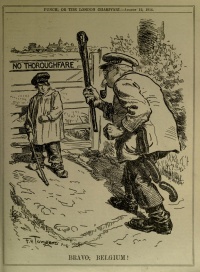

As early as 26 July, German Chief of Staff Helmuth von Moltke (the Younger) (1848-1916) drafted an ultimatum to the Belgian government, demanding the right of passage for German troops en route to France. On 2 August, the German envoy in Brussels delivered the ultimatum; the Belgians had twenty-four hours to respond. In a nocturnal meeting, the government and Albert I, King of the Belgians (1875-1934) decided to face the risk and reject the ultimatum: accepting it would “sacrifice (...) [the Belgian government’s] duty towards Europe.”[5] Indeed the 1839 treaty which had declared Belgium neutral was “a cornerstone of European international law”: it subjected relations between European powers to legal rules and preserved the safety of smaller states.[6] Since Belgium owed its continued existence to international law, rejecting the ultimatum was a form of self-defense in the long run. In the short run, the risk was appalling.

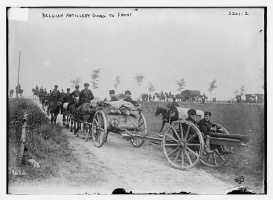

On 3 August, the Belgians woke up to a war which, with over three generations of neutrality, they had ceased to believe possible in their lifetime. (The army, 234,000 strong, had been mobilized on 31 July, but merely to stand guard.) Yet citizens seem to have rallied around precisely this neutrality, cursing war in the same breath as they did the great power that forced Belgium into war. Systematic surveys on the public mood are lacking, but existing reports (police files, private diaries, newspaper accounts) show a mixture of dread and resolve similar to what obtained elsewhere in Europe, with the cities generating the most patriotic effervescence, complete with anti-German charivari. 18,500 men volunteered to serve, a sizeable number given that the latest and largest contingent of recruits, that of 1913, had yielded 33,000.[7] Skepticism of the government’s decision remained diffuse and the opposition Belgian Workers’ Party and the Flemish Movement championed national defense. On 4 August, King Albert I appeared before Parliament to announce Belgium’s entry into the war, even as Otto von Emmich’s (1848-1915) Army of the Meuse crossed into Belgian territory near Liège.

If the German armies were to pass quickly through the bottleneck created by the decision not to violate Dutch neutrality, they had to take the forts of Liège before war was even declared on Belgium. Massive deployment of modern weaponry got the better of the city and the fortresses by 16 August. Still, the siege took eleven days instead of two, a setback avenged on locals, nearly 850 of whom were killed by the invading army on 5-8 August alone.[8]

If the invasion was a shock, the subsequent German advance was slow. During the siege of Liège, the Belgian field army – ordered to delay an invader’s advance, not to let itself be demolished – retreated in stages northward to Antwerp, the fortified “national redoubt.” The king and government had retreated there by 20 August, the day when Brussels, an open city, fell without a fight.[9] Meanwhile, in the south-east, the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) and Charles Louis Marie Lanrezac’s (1852-1925) forces had to retreat after encounters in Mons and Charleroi. By 23 August, they had been forced out of Belgium. To cut off the German communication lines, the Belgian army both before and after the battle of the Marne made sorties from Antwerp. In response, on 28 September, a corps under Hans von Beseler (1850-1921) started besieging Antwerp, which fell on 6 October. Rupert Brooke (1887-1914) described the sight of the burning city as “a Dantesque Hell, terrible,” adding that he later saw “a truer Hell. Hundreds of thousands of refugees, their goods on barrows & hand carts & perambulators & waggons, moving with infinite slowness out into the night.”[10] Of the Belgian troops, about 4,000 were captured, bringing the number of Belgian prisoners of war to 30,000. Another 30,000 escaped to Holland, where they were interned for the duration. But the main body of the Belgian army had got away over a pontoon bridge across the Scheldt; it retreated to the westernmost part of Flanders and joined the allied armies.

The depleted Belgian army’s final stand on the river Yser began inauspiciously. But engineers used the low-lying region’s ancient system of canals and sluices to inundate the frontlines. This halted the German advance; the battle of the Yser was over on 2 November. To the south, the German assault on Ypres ended ten days later.[11] As had other armies, the Belgian army had suffered its greatest losses during mobile warfare: half of the war’s 26,000 Belgian military dead were killed between 4 August and 2 November 1914.

The invading armies killed 5,500 civilians – mostly men, but women and children as well. The bulk of the violence took place from August, with explosions of violent paranoia in places like Leuven, Aarschot, Dinant, and Tamines, to October, when the advance to Western Flanders occasioned a last series of smaller-scale massacres. These occurred wherever the attackers suffered inexplicable setbacks and were driven by an army culture suffused with fear of civilian snipers (franc-tireurs). Much ritual enacting of conquest accompanied the violence: local dignitaries such as burgomasters and priests were singled out for humiliation. Survivors testified that people were made to sing praise to the German Empire. An improvised triumphal arch put up on a bridge in a badly battered Brabant village bore the inscription “To The Victorious Warriors.”

On the Entente side (as well as among neutrals), public outrage over “German atrocities” and, beyond this, over the violation of a small state’s neutrality, was intense. If we define “war culture” as the set of beliefs that allowed populations to countenance war, then Belgium became a trope in the emerging war culture of the Entente, eulogized as a martyred nation which had “sacrificed itself” to the cause of justice. The praise lavished on “Brave Little Belgium” strengthened Belgians’ sense of national purpose. But, meanwhile, they had to settle into a war routine.

1915-1916: Settling into a War Routine↑

A Segmented Society-at-war↑

Because of invasion, occupation, and mass flight, Belgium-at-war was a constellation of dispersed constituencies, strapped for cash, out of their depth, and in only intermittent touch with each other, which led to misunderstandings. The army, the occupied civilians, the refugees, the government, and the king experienced the war in different worlds. The army held the Yser front in the northwestern corner of Belgium, where the king, its de facto commander, also resided. The cabinet and its threadbare staff stayed 300 kilometres further west, near Le Havre (Normandy), cut off from the population and from most members of Parliament. Dispersed refugee communities entertaining widely differing views of the war resided in France, Britain, and the Netherlands. The occupied territory, where more than eight out of ten adult Belgians spent the war years, was cut off from the outside world, including the army. Belgium, then, possessed no “home front” in other belligerents’ sense of the term; its war was fought in exile, while the resources of the occupied country were forcibly diverted to the German war effort. This put its stamp on the Belgian war experience and war effort.

The Situation in November 1914↑

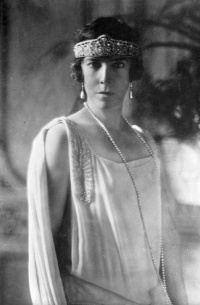

In late November 1914, Belgium, as a belligerent, was in bad shape. On the Yser, the 52,000 men of the field army (down from 117,500) were lacking in all resources and desperate at the lack of news from their loved ones. The nearness of the intensely popular royal couple – Elisabeth of Bavaria, Queen of the Belgians (1876-1965) adopted a persona as nurse – provided some consolation. Meanwhile, the Belgian government (now a government “of national unity” with the addition of one Socialist and two Liberal ministers to the Catholic cabinet) had regrouped in French exile. During the invasion phase, almost 1.5 million Belgians had fled the country, the largest exodus in Low Countries history. Belgium was now largely overrun – 2,598 of its 2,636 municipalities were occupied – and the situation was dire, with massive internal flight, homelessness and acute material shortages: the U.S. envoy to Belgium, Brand Whitlock (1869-1934) noted that “gaunt famine stalks nearer.”[12] From November 1914 onwards, a form of war routine was re-established at the Yser, in exile, and in occupied Belgium.

Front↑

Through 1915-1916, the Belgian army regrouped.[13] It dug in – or, rather, in this waterlogged terrain, it used sand-bags to buttress its front, which extended to thirty-two kilometres from June 1916. In August 1915, the troops received new khaki uniforms; later on, Adrian helmets. The hinterland was built up with a portable light-railway system, telephone lines, barracks, and other amenities; medical and other services improved markedly. All of this was largely on credit from the Entente (as well as the United States) and on a budget: troops joked that the Armée Belge-stamp on military furnishings stood for “Armen Belz” – poor Belgian.[14]

Between February and August 1915, some 34,000 men – the early volunteers, plus conscripts – joined the ranks after training in Normandy.[15] Subsequently, conscripts from unoccupied West Flanders joined as did the volunteers who managed to escape the occupied country via the Netherlands and, from 1916, conscripted refugees. Altogether over 130,000 troops joined over the course of the war.[16] This is not a large number. At war’s end, only 20 percent of Belgian men of military age would have served, compared to 54 percent in Britain, 86 percent in Germany, and 89 percent in France.[17] Men from the occupied country could not be called up. It was true that, through 1915-1918, some 10,000 volunteers did manage to join the Yser army which represented a major resistance effort.[18] Apart from the ones who made it, an untallied number of young volunteers were thrown in jail or were killed at the Dutch border. Those who helped them escape faced the death sentence.

Still, the yield for the Yser army was modest compared to four years of an unhampered wartime levy. Then again, the Belgian state was reluctant to call up even those men it could reach, as demonstrated by its conscription of refugees. Postponed time and again to keep the army small and out of major allied offensives, the refugee draft was ultimately introduced in the summer of 1916. Even so it comprised many exemptions and expressed a preference to enrol men in the Belgian armaments industry in Britain and France. “The Government,” stated the draft decree, “feels duty bound to employ those forces still at its disposal with the greatest possible discernment,” leaving in place “those who dedicate their work and expertise to [the armaments] industries.”[19] As for Congolese troops, the Belgian government was unwilling to raise much of a force, let alone deploy it abroad. “It is bad for their civilization and the prestige of the white race in Africa,” Minister of Colonies Jules Renkin (1862-1934) wrote in 1916, adding, “it is our moral obligation not to involve these people, whom we must protect, in this terrible mess.”[20] In early 1918, Renkin restated his conviction that levying African troops for the European war “would, in future, be a source of grave troubles in the Congo.”[21] A grand total of thirty-two Congolese soldiers served on the Yser front.

This reluctance to mobilize men was of a piece with the king’s unwillingness to commit troops to allied offensives, which he considered to be wasteful impositions on a neutral. Recent scholarship demonstrates that this reluctance reverberated across the Yser army. In 1916, for instance, following entreaties from Joseph Joffre (1852-1931), the Belgian General Staff grudgingly agreed to send 17,750 men of the 1st Division to learn offensive techniques with the French army. The men left in December 1916 and were back at the Yser in February 1917, having mastered new skills. But no further trainees were sent and the cadres’ stance remained as fundamentally defensive as ever, if flexibly so, shifting as it did from linear defense to defense in depth.[22]

Scholars have analyzed the creation of meaning on the Yser front through troops’ private writings, trench journals, the army’s official journals,[23] and sources that document the dynamics of honors and rewards; work is in progress on the role of junior officers and chaplains and of arrangements – military and civilian, official and private – for soldiers’ welfare.[24]

Exile↑

The government-in-exile was wedged between demanding allies and a reluctant king. It channelled the resources it could muster – loans, international aid, Belgian assets abroad – toward the Belgian war effort. It upheld international solidarity by reminding the world of Belgium’s stance and plight. A Belgian Documentary Bureau rebutted German accusations, producing, among others, a classic study on franc-tireurs by the young sociologist Fernand Vanlangenhove (1889-1982). Famous Belgians such as the Nobel Prize-winning playwright Maurice Maeterlinck (1862-1949) were sent on lecture tours. Secret surveys enabled Cabinet ministers to chart attitudes in the occupied country, but not to influence them; meanwhile, their authority over Belgians in exile increased somewhat, especially regarding munitions workers.

Among the refugees too, matters settled. Most of them returned to Belgium after the occupation regime had guaranteed their safety – and threatened to confiscate their property. Still, some 600,000 Belgians remained abroad until the Armistice. Charities and government services (foreign and Belgian) devised long-term arrangements, some quite restrictive: in the Netherlands, destitute refugees had to live in camps; Britain monitored Belgian munitions workers so as to avoid labour and draft disputes. Only in France did Belgian refugees find their way into the wartime labour market (munitions, agriculture) more informally. Overall, the refugees formed a heterogeneous group in terms of background, circumstances, and willingness to commit to the Belgian war effort.

Occupation↑

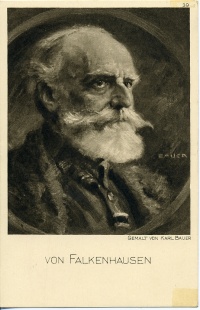

In the shift between the mayhem of the invasion and the routine of occupation, local elites played an essential role. Many had stayed on, unlike what would happen in 1940; this made for some continuity and public trust, and an improvised modus vivendi with the new occupation authorities. These occupation authorities were of a nature both military and civilian in the largest segment of occupied Belgium, the Government-General, with its seat in Brussels.[25] The post of Governor-General, a kind of viceroyal position, was occupied successively by three elderly East Elbian aristocrats and career officers, the generals Colmar von der Goltz (1843-1916) (during the war’s mobile phase; he left in November 1914), Moritz von Bissing (1844-1917) (from December 1914 to his death in April 1917), and Ludwig von Falkenhausen (1844-1936) (until the war’s end). They were not officials of the German state and answered only to the emperor. They employed German civilian administrations, which answered to the chancellor – to a point – and received some limited scrutiny from the Reichstag. This hybrid system made for clashes of authority, while creating some latitude compared to completely military regimes.

The Belgian national bureaucracy was not, as yet, dismantled; although the Cabinet ministers were in exile, some ministries – such as Public Works, Agriculture, and Arts and Sciences – continued to take care of day-to-day affairs, albeit with an ever-shrinking remit. Railways and Posts and Telecommunications were taken over by the German military; Foreign Affairs, War, and Colonies operated entirely in exile. Parliament was disbanded; national public life shriveled. The commune became the real locus of “native” administrative continuity. Municipal governments functioned throughout the war, albeit under heavy German control. Relatively autonomous even in peacetime, they now increased their remit: they levied taxes, issued “municipal” money, created public work schemes, and devised welfare measures.

The occupation regime was not the same across Belgium. The Governor-General administered two-thirds of the occupied country only. The area closest to the front, comprising some 22 percent of the occupied population, formed the Etappengebiet.[26] This was an exclusively military and much more repressive regime under the command of the German Fourth Army. The Belgian coast was also under a purely military regime: the Marinegebiet.[27] Across these regions, the occupation administration branched out and grew in personnel. This was largely German personnel: the lines were sharply drawn, in contrast to the Second World War, when the occupation authorities would endeavour to work as much as possible with German-friendly local administrators.

A first and urgent issue was that of food. Belgium had not been self-sufficient in generations; it exported potatoes and sugar beets, but imported most of its cereals and other essentials. It now threatened to starve between the allied blockade and overstretched Germany’s refusal to provide for the occupied territories. In response, the Brussels municipal government and a conglomerate of Brussels charities, aided by industry magnate Ernest Solvay (1838-1922) formed what would become the nationwide Comité Central de Secours et d’Alimentation (hereafter Comité).[28] Presided by entrepreneur Emile Francqui (1863-1935), the Comité sought international aid through Herbert Hoover (1874-1964), then a forty-year-old businessman in London.[29] Hoover’s Commission for Relief in Belgium (hereafter Commission), a neutral organization, centralized funds, purchased and shipped food, and guaranteed its safety from German confiscation.[30]

The occupation authorities at first welcomed the relief effort as a means to stave off famine and revolt, but they came to resent the Comité’s prestige as a de facto government. “The common opposition of all Belgians vis-à-vis the Germans,” wrote one leading official in July 1916, “is concentrated in the [Comité].”[31] To escape German control, the Comité remained an ad-hoc organization, yet it was vast in size (125,000 agents) and remit. It sold the relief foodstuffs in special stores (the destitute received them free, others paid) and used the proceeds to grant aid, charting needs and coordinating welfare as it did so. Its regimentation of food displeased many a farmer, baker, grocer, and consumer. But it did stave off famine. It also yielded national health benefits: infant mortality even briefly declined compared to pre-war times. The relief effort also preserved a modicum of public confidence by keeping black marketeering in check to some degree.

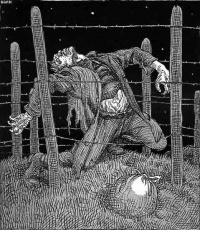

Belgium, once so tightly integrated and so open to the outside world, was now crisscrossed with internal borders and closed off all around. Civilians were confined to their own commune; even the shortest trip required a permit. Public transportation was infrequent and expensive; private vehicles (bikes, horses, cars) were confiscated or banned. Distances were once more expressed in walking hours. In addition, in 1915 the German corps of engineers erected a high-voltage electric fence along the 300-kilometre border between occupied Belgium and the neutral Netherlands – the first such wall in history.

Under these restrictions as well as others (on the press, private correspondence, and meetings), some civilians still attempted to support the national war effort. They refused to work for the German army. In response to the railway network’s takeover by the Militär-Direktion der Eisenbahnen to transport troops, Belgian machinists in two major locomotive repair facilities refused work in 1915. In that same year, stone quarry workers in Hainaut went on strike, since their production contributed to the German defense works. Likewise, municipalities refused to deliver war materials, such as barbed wire; in retaliation, hundreds of local dignitaries were jailed.

Many strove to deny the occupation regime legitimacy, by, for instance, maintaining “patriotic distance.”[32] While the middle classes practiced this most assiduously, it signified respectability across the social spectrum. “In all those four years,” a woman who had grown up in a working-class family in West Flanders would later state, “my father hardly spoke to [any Germans] unless he had to.”[33] It behooved patriots to declare, in the words of the January 1915 pastoral letter by Cardinal Désiré Joseph Mercier (1851-1926), that “This Power is not a legitimate power.”[34] Informal networks of citizens launched a clandestine press, with seventy-seven separate titles, some ephemeral, others long-lived, the most vibrant of occupied Europe.[35] It reported on allied successes and on the 1914 massacres (a taboo subject), reminded readers of why Belgium was at war, and reprimanded “German-friendly” Belgians.

In another form of resistance, escape networks smuggled Entente soldiers and Belgian volunteers out of the country. (Even after the completion of the electric fence on the Belgian-Dutch border, some 25,000 people were smuggled out – twenty per day.[36]) These networks ranged from the modest to the elaborate. One network of 179 men and women (plus an entire “grey zone” of occasional helpers) was dismantled in the summer of 1915; a vast trial before a German military tribunal ended in the execution of the young Belgian architect Philippe Baucq (1880-1915) and, notoriously, of the Englishwoman Edith Cavell (1865-1915),[37] matron of the Brussels school for nursing; her death resonated worldwide.[38] Inside Belgium, such capital punishments were all the more shocking as no one had been executed there since 1863.

Further support for the allied and Belgian armies came from secret intelligence networks. As hinterlands to an enemy army, Belgium (as well as northern France) yielded thousands of spies, organised in 250 networks ranging from the modest, such as that of the young saleswoman Gabrielle Petit (1893-1916), to the elaborate, such as that of the telegraph operator Charles Parenté (1878-1916). These networks were embedded in extensive informal support systems. By contrast, German-employed spies on the other side of the Western Front had to operate in more isolated ways.[39] Secret intelligence agents were paid, yet never in a way commensurate with the risks. As a German analyst stated after the war, “nowhere, at any time, it seems to me, have people spied more fanatically and with more of a spirit of sacrifice than in Belgium.”[40] Most networks worked for the British intelligence services, which were more efficient than the Belgian and French ones which German counterespionage had practically annihilated by mid-1916. In addition, the British services would, from 1917, offer military rank, which mattered greatly to agents keen on belonging to “an auxiliary branch of the army, complete with ranks, batallions, discipline, and enlistment.”[41]

Still, for people at continued risk of starvation or armed violence, defiance had to alternate with co-existence. While attempts to channel Belgian resources toward the German war effort were generally resisted with far greater vigour than they would be during the Second World War, and ideological collaboration was rare,[42] “entrepreneurs’ attitudes were more variable” than would appear from post-Armistice reports.[43] The Belgian government, in unison with Émile Francqui and other major actors in the occupied country, certainly did not call for a work stoppage. As Prime Minister Charles de Broqueville wrote, since October 1914, and even more systematically since May 1915, Belgian enterprises had “showed themselves intransigent when it came to producing materials lacking in Germany, but boldly opportunistic when it came to others,” thus “[preserving] Belgium from starving, freezing, and industrial ruin.”[44] This policy was met halfway by Governor-General von Bissing’s “conservation policy” of tempered exploitation which strove to revive Belgian manufacturing under German control. The Belgian economy under occupation, then, possessed significant breathing space – at least until the policy of extreme exploitation was introduced in 1916-1917 (see below).

In addition, the interests of occupier and occupied merged in some domains, such as the combating of epidemics and fires and the maintenance of public order. These shared aims made for improvised if tense partnerships that did not correspond to the image of an entire society forming a front against the invader. Yet the boundaries of the modus vivendi remained clear to the occupied. The Belgian judiciary, for instance, following the Hague convention of 1907, remained in operation for routine matters. But it refused to deliver civilians to German military courts, or to comply with a 1915 decree that criminalized the refusal to work (so as to force Belgians to work in Germany): “cooperation with the occupying power in penal matters (...) was a threshold” which magistrates refused to cross.[45]

The war routines established across the different segments of Belgium-at-war, then, in their pragmatism, fell short of the self-immolating stance expected of “The Nation That Died For Europe” (as an Allied trope went).[46] At the same time, across those segments, a robust consensus existed regarding the war effort, and, especially, regarding its end goal: the restoration of Belgian independence.

German Designs on Belgium, 1914-1918↑

Meanwhile, German plans for Belgium took further shape. Imperial Germany had not gone to war to capture Belgium, but it became a war aim once stalemate set in. Even so, designs on Belgium fluctuated with the military situation, and no consensus existed among imperial decision-makers. Yet two conditions remained in force until the last moment. First, Belgium had to be subordinated to the German war effort. Second, it had to stay in the German orbit; National Liberal leader Gustav Stresemann (1878-1929) expressed the thought of many when he declared that a land “conquered with so much blood must not again be relinquished.”[47]

Subordination to the German war effort was, above all, material in nature. From December 1914, the occupied country had to pay a monthly war tax of 40 million francs, twenty times the sum total of all pre-war direct and indirect taxes. In return, the Government-General (though not the army in the Etappengebiet) pledged to limit further exactions – yet it did impose further taxes in the form of fees for all manner of permits and of heavy fines for even minor infringements.

In the second half of the war, this policy gave way to extreme exploitation under the auspices of the Third Supreme Command. The monthly tax rose to 50 million, then 60 million francs. An expanding system of “Centrals” (Zentralen) controlled and siphoned off locally produced foodstuffs and other goods. A February 1917 decree placed Belgium’s ailing industries under complete German control. Unless firms agreed to work for the occupation army, they were closed down, their equipment was seized and shipped to Germany, and their buildings demolished. Entire manufacturing regions were stripped, including of transport infrastructure. The policy of extreme exploitation also, tragically, led to the deportation and forced labour of Belgian workers. Forced labour was introduced, violently and messily, in October 1916.[48] After worldwide protest (including in the Reichstag), it was halted in February 1917 for the Government-General, but continued until war’s end in the Etappengebiet.

Forced labour, a brutal measure of last resort, signalled the end of hopes for a thriving Belgian economy under German control. These hopes slotted into a larger aim of creating a basis of common interest, perhaps even legitimacy, for the occupation regime. One major legitimizing endeavour was ethnic-cultural in scope: a pro-Flemish policy (Flamenpolitik) addressed Flemish linguistic grievances. This was a play for acceptance, and an attempt to divide the occupied population, but it also had emotional benefits for Germany-at-war: Flamenpolitik redefined the invasion of Belgium as a liberation – that of a “brother” people from an artificial state that suffocated the Germanic element. As Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg (1856-1921) told the Reichstag in April 1916, Germany pledged never again to abandon its Flemish brethren to “frenchification”. Flamenpolitik was pursued by different actors, who did not always agree among themselves: the Governor-General’s Political Department and other units; officers in the Etappengebiet; and a plethora of politicians, lobbyists, and experts from the German home front. A high point was the creation, in October 1916, of the all-Flemish University of Ghent. In March 1917, in a move internally criticized as rash, the occupation authorities divided Belgium into Flemish and Walloon regions and declared Brussels the capital of Flanders.

In March 1917, representatives of the “Council of Flanders”, a self-appointed body with no legislative or executive power, visited the chancellor in Berlin. By then, Flamenpolitik had created a political culture of sympathetic Flemings: an estimated 20,000 of them (occasional sympathizers and signatories of petitions included) who called themselves “activists,” a term chosen to convey a vigorous pro-Flemish stance. The emergence of activism met with enthusiasm in parts of German public opinion. Friedrich Naumann (1860-1919), for one, greeted the Council of Flanders’ visit with the words: “Henceforth, Flanders’ plight is Germany’s plight; Flanders’ hopes are Germany’s hopes.”[49] Yet creating an activist milieu did not mean gaining the Flemish population at large and hopes to attract Flemish Movement leaders fizzled, as most of them publicly refused to accept rights proffered by an occupation regime. Occupation officials acknowledged among themselves that their activist contacts were largely “leaders without troops.”[50] Unable to garner a significant following or enter the decisive terrain of municipal authority, activists were reduced to brokering favours (thus confirming public criticism of activism as a form of war profiteering) and producing a vast corpus of anti-Belgian rhetoric. Activism – both the Flemish version and its smaller-scale Walloon counterpart – had its uses on the German home front, but it did not provide the occupation regime with useful local associates.

1917-1918: War-Weariness and Renewed Resolve↑

For all that occupied civilians largely rejected activism, the consolations of patriotism were wearing thin. In 1916, Brussels celebrated the forbidden national holiday of 21 July; no such effort was made a year later. In occupied Belgium as elsewhere, 1917 marked a crisis of war legitimacy. The failed allied offensive on the Somme, the fall of Bucharest and other bad news from the fronts, coupled with growing material exhaustion, generated war-weariness among occupied civilians. Manifestations and pamphlets in favor of peace proliferated from December 1916; the 1914 rejection of the ultimatum no longer commanded the same awe. Mutual recrimination rose: a mid-1917 report by Governor-General von Falkenhausen stated that the occupation regime was detested as much as ever, but that the occupied Belgians detested one another, too. Various segments of society accused others of profiteering; the burden of “sacrifice” seemed unequally borne.

Occupied Belgium was riddled with class tension. Relief arrangements broke with old laissez-faire attitudes but did not question hierarchies of class and gender. Impoverished middle-class people did not have to queue for soup. Soldiers’ wives received aid in kind; officers’ wives had an allowance. Most women received relief (a form of charity) instead of unemployment benefits (a social right). In addition to the tensions generated by relief arrangements, the occupation regime’s deportation of the jobless hit only the working classes, thus dividing those who had to live under this spectre (or who took on “voluntary” work as a last resort) from those who did not.

Alienation also ran along generational lines: young men, especially, found themselves resented by patriots with sons at the front. Young bourgeois men were under especial pressure to try to escape and enlist in the Yser army, in spite of terrible danger. In response, some accepted the occupation regime’s offers of higher education and of employment. Young literati defied convention, published in new magazines, and made German friends. Others, more compromisingly, worked for German counterespionage. Belgian informers, as recent scholarship demonstrates, were overwhelmingly young men and women: of the 248 identified (15 percent of them women), 72 percent were under thirty-five; their youth suggests they were only “feebly anchored” socially and professionally, and may have been inspired by a sense of “rebellion against the established order and the all-pervasive patriotic mores.”[51] The alienation of youth merged with alienation over language among the students at the new all-Flemish University of Ghent, a few hundred in number. Activism marked a coup in the Spring of 1918, when two Flemish deserters fresh from the Yser front made a spectacular appearance at a theater in Ghent.

This was a major symbolic development. Through the war years, occupied civilians and the Yser troops, though separated, referred to each other constantly. Trench journals, which were usually regional or local in scope, gathered as much information as they could to present soldiers with news about their inaccessible home towns or villages; and the troops were enjoined to refrain from sexual and other misconduct by thoughts of home. Conversely, civilians in the occupied country saw the front as the epitome of “sacrifice.” But there was almost no direct communication – until the Ghent event. Staged by the German Fourth Army, it was meant to undermine Belgian legitimacy and strengthen Flamenpolitik. The two soldiers had belonged to the so-called Front Movement, a pro-Flemish group within the Yser army. Their arrival provided activism with front prestige. It also demonstrated the salience of the Flemish issue on the front. The Front Movement condemned the predominance of the French language in an army where Flemings were overrepresented (an estimated 65 percent, as compared with 55 percent of the Belgian population). Grown out of student associations and Catholic prayer groups, it became more radical in 1917, staging nocturnal demonstrations and issuing open letters to King Albert. The Front Movement – which reached an estimated 5,000 men, occasional supporters included – was part of the wider wave of discontent across belligerent Europe in the “impossible year” 1917. It was by no means the only expression of discontent in the Yser army, as research in diaries and correspondence shows. Desertion figures tell a similar story: through 1916, 1,203 soldiers went AWOL; that number rose to 5,630 for the next year with 1,007 in December 1917 alone. The rise continued through the spring of 1918.[52] Meanwhile, among the Belgians in exile, protest against the draft and against conditions in munitions factories was rife.

Yet both the Yser and the home front endured: like most other belligerent societies, Belgium re-rallied around the basic notion of national defense. At the front, the crisis in troop morale never seriously shook a core consensus over the necessity to hold out, endorsed even by the Front Movement, which would disavow its “activist” deserters after the war. Foreign observers, including even the wary French military attaché, considered Belgian troop morale satisfactory. The German 1918 Spring offensive strengthened defensive resolve. At first, no more than that: as late as 10 July, King Albert refused to place the Yser army under general allied command to avoid offensives. But the success of the allied counter-offensive changed his mind, and by August he agreed that the Belgians ought to participate in the liberation of Belgium. Meanwhile, the continued German refusal to commit to restoring Belgium’s status quo ante put paid to last-ditch secret negotiations. The Belgian army (170,000 men), together with French and British divisions, formed the Army Group Flanders under the king’s nominal command; it played a significant role in what would become the liberation offensive, from its departure from the Yser on 28 September to the Armistice, by which time it had reached the Scheldt.

Under occupation too, in spite of the absence of the state, a form of “remobilization” had emerged. There were fewer espionage networks but they became more efficient, the pinnacle being the vast and intricately organised “White Lady” network, which worked for the British War Office.[53] Patriots launched new underground papers such as the high-brow anti-activist periodical De Vlaamsche Wachter (The Flemish Guardian), launched in Antwerp in January 1917, and the equally high-brow Le Flambeau, founded by Brussels academics in April 1918. Meanwhile, the Comité, now operating under Spanish and Dutch guarantee because of the U.S. entry into the war, struggled amidst deepened scarcity to at least limit the rampant malnutrition of children; its action was aided by the Belgian judiciary, which stepped up its prosecution of food fraud. Meanwhile, public remonstrations against the occupation regime’s policies galvanized a sense of resistance – as did the pitiful sight of the repatriated forced-labour deportees. In protest against the occupation regime’s protection of activists – magistrates who had arrested two leading activists were deported to German prisons – the judiciary went on strike from February 1918 to the Armistice. Through these and other actions, civilians’ refusal to consider the occupation regime a legitimate authority endured, as German officials would recognize after the war.

Aftermath↑

The end of the war meant the reuniting of the different segments of Belgium-at-war; the return of the Belgian state; and the return – or reconquest – of legitimacy through a renegotiated social contract. Starting before the Armistice, King Albert entered a succession of just-liberated Belgian cities, from Ostend – where the royal couple made an impromptu nightly visit – over Bruges to Ghent, reached on 13 November. The royals’ “Joyous Entry” into Brussels on 22 November – the term deliberately referred to traditional political legitimacy – was meticulously prepared by the municipal authorities, so as to express (and create) public consensus over the return to order. The parade did not disappoint. The monarch, at the head of Belgian and allied troops, rode past cheering throngs. Ten stucco monuments commissioned for the occasion represented Edith Cavell in a “Homage to England,” as well as “Our Great King and Valiant Army,” “Belgium Halting the German Wave,” “An Allegory of Peace,” and similar themes.[54] Albert’s speech before parliament made it clear that the return of legitimate authority necessitated changes in the social contract, specifically the immediate introduction of simple universal suffrage for all men over twenty-one. This reform, pushed through without a constitutional revision, was resented as a “coup” by conservatives, but few doubted that the abolition of the “plural” franchise (and the lowering of males’ voting age from twenty-five to twenty-one) was a priority in a cultural context that exalted soldiers’ sacrifice.[55] Even if the king’s speech, significantly, stopped short of extolling sacrifice, instead pointing out that he had been sparing of soldiers’ lives – a passage greeted by especially thunderous cheers.

Veterans, of course, as mentioned earlier, represented a relatively small portion of society compared to other belligerents. Women’s suffragists pointed out that if blood sacrifice was the criterion for granting citizens the vote, a majority of Belgian men would benefit from the plight of a minority; and that if the notion of “sacrifice” were expanded, it ought to bestow its benefits on women who had carried some of the heaviest burdens under occupation.

Indeed the unique experience of occupation inflected Belgium’s exit from war. The liberation saw a brief spell of public violence against “traitors” – suspected war profiteers, informers, activists, and women who had been intimate with German soldiers. No one was lynched, but civilian crowds, sometimes aided by returned soldiers, destroyed property, beat up men, and cut off women’s hair amidst appalling injury and abuse. Rumors of the public humiliation of the “femmes à Boches” spread from the liberated to the still-occupied parts of Belgium, thus creating “a precedent, which in a way legitimized [in advance] those planning to settle scores.”[56] Bitter feelings were exacerbated by the fact that, across the territory (and by no means in the front zones alone), many civilians, especially children, were mutilated or killed by ordnance left, or even hidden, by departing German troops. Other forms of lasting physical damage included children’s stunted growth – the percentage of children with rickets had risen – and adults’ bodily exhaustion which led to vastly increased mortality.[57] Materially, too, Belgium had been hit very hard by the war, as painstaking tallies of destroyed homes, farms, roads, railways, workshops, and factories would soon demonstrate.

Vast damage led to high expectations, which were crushed by the outcome of the Paris peace conference.[58] “In all the years of the war, I have never seen Belgium quite so depressed and discouraged,” wrote Brand Whitlock on 2 May 1919.[59] Yet a 11 May demonstration against the peace treaty, which accused Belgium’s allies of ingratitude for “August 1914,” proved a dismal failure: the mainstream press, probably echoing public opinion, expressed disgust with this failure to acknowledge the allies’ loss of lives in liberating Belgium. In general, feelings of bitterness were channeled into the work of reconstruction, a pattern which was visible at the granular level. The Forges de Clabecq, for instance, a metallurgical enterprise in Hainaut despoiled and damaged by the occupation regime, started rebuilding in late November 1918; one year on, it started placing orders for German machinery.[60]

In the meantime, the wave of public violence had subsided as the criminal justice system (consisting of military courts up to April 1919) resumed operations. Likewise, the fiscal system fostered legitimacy by addressing and channeling rancor against “profiteers”: a tax on war profits was levied in 1919. The following year, succession rights rose by half to finance a state endowment for veterans; and, between 1919 and 1925, spending shifted somewhat to the benefit of the working classes, if not to the detriment of the goal of recasting bourgeois Belgium. Likewise, existing hierarchies did not budge with regard to gender: women’s suffrage was only granted to former political prisoners (no effort was made to tally these women) and to widows and mothers of dead soldiers and executed civilians, the former only if not remarried, the latter only if widowed.

Belgium’s war monuments were local affairs, ranging from the grand to the modest. One particularity, which Belgium had in common with occupied northern France – though not, it seems, with other formerly occupied parts of Europe – was the theme of the fusillé(e), the man or woman executed for acts of resistance, and now held up as an example of civic virtue. A few dozen such memorials – some, full-scale bronzes or even sculpted allegorical groups; others, subdued bas-reliefs – were unveiled across Belgium in the post-war years. They took their place in cityscapes and featured on postcards which further integrated these lieux de mémoire into everyday life. In general, the war and its artefacts became part of the vernacular. Adrian helmets (and the occasional Pickelhaube) served as flower-pots; in Brussels, a meeting-house named after the heroine Gabrielle Petit offered working women of slender means a place to rest, have a cup of tea, and freshen up. On the Belgian coast, a pancake stand, rather tastelessly, advertised mementoes of Charles Fryatt (1872-1916), the English captain executed for having rammed a German submarine and remembered as a war hero. Intangibly but structurally, the war’s legacy also wove itself into daily life through family dynamics. The vociferous patriarchal discourse of the post-war years did not stop women from entering the workforce and families from limiting births in discreet but sturdy remembrance of wartime vulnerability.

Perhaps paradoxically, Belgium’s least local and most vocal monument to the dead was a counter-nationalist monument: the 1930 Yser Tower, a defiantly anti-Belgian memorial whose inscription “All for Flanders – Flanders for Christ” was a prime expression of Flemish counter-nationalism. This largely Catholic, small-town and middle-class movement had arisen less in response to the war itself as to the putative excess and injustice of post-war mass society. The myths it created around activist “martyrs” kept the theme of “sacrifice” alive. By contrast, the liberal narrative of Henri Pirenne’s 1928 synthesis, while accusatory in places, had no use for “sacrifice,” as it was couched in tones of cultural demobilization. It could afford to, for it documented what it saw as a triumph: civilians’ resilience under occupation seemed proof of the endurance of parliamentary democracy and of the irrelevance of “that theory of races, the most false but also the most pernicious ever,” which, according to Pirenne, had guided Wilhelmine Germany’s conduct of war.[61] Yet Pirenne’s hopeful liberal view did not translate into Belgian war literature, which stressed discord and bitterness.[62] This literature could have developed a counternarrative of victimization, but it lacked the confidence, the coherence, and the audience to do so; and, in spite of some interwar successes, none of it made it into the international literary war canon.

Brief Conclusion↑

Belgium’s war experience, and the lessons that could be drawn from it, went, as it were, underground. Yet, as a segmented society-at-war, the particularities of this war experience shed a specific light on the war’s dynamics of cultural and social mobilization. Those particularities are also instructive with regard to the security conundrums of small and prosperous states in geopolitically sensitive regions.

Sophie De Schaepdrijver, Pennsylvania State University

Section Editor: Benoît Majerus

Notes

- ↑ 7,639,000 in 1913. Bartier, John et al.: Histoire de la Belgique contemporaine 1914-1970, Brussels 1975, p. 275.

- ↑ Quoted in De Schaepdrijver, Sophie: La Belgique et la Première Guerre Mondiale, Frankfurt-Brussels 2004, pp. 141, 40.

- ↑ Zolberg, Aristide: The Making of Flemings and Walloons: Belgium, 1830-1914, in: Journal of Interdisciplinary History 5 (1974), pp.179-235, p. 210.

- ↑ De Muêlenaere, Nel: An Uphill Battle: Campaigning for the Militarization of Belgium, 1870-1914, in: Journal of Belgian History 42/4 (2012), pp. 144-179.

- ↑ De Ridder, Alfred: Histoire diplomatique 1914-1918, Brussels 1922, pp. 134-135. (La Belgique et la Guerre Vol. IV.)

- ↑ Hull, Isabel V.: A Scrap of Paper. Breaking and Making International Law during the Great War, Ithaca 2014, pp. 17-22.

- ↑ Zuber, Terence: Ten Days in August: the Siege of Liège 1914, Stroud 2014, p. 60.

- ↑ Horne, John / Kramer, Alan: German Atrocities 1914: A History of Denial, New Haven 2001, p. 13.

- ↑ Kesteloot, Chantal: Brussels, in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War, ed. by Ute Daniel, Peter Gatrell, Oliver Janz, Heather Jones, Jennifer Keene, Alan Kramer, and Bill Nasson, issued by Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin 2015-06-30. DOI: 10.15463/ie1418.10674.

- ↑ Quoted in Fairman, Elisabeth (ed.): Doomed Youth: The Poetry and the Pity of the First World War, exhibition catalog, Yale Center for British Art 1999, p. 3.

- ↑ Spencer, Jones: Ypres, Battles of, in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War, ed. by Ute Daniel, Peter Gatrell, Oliver Janz, Heather Jones, Jennifer Keene, Alan Kramer, and Bill Nasson, issued by Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin 2015-02-13. DOI: 10.15463/ie1418.10552.

- ↑ Nevins, Allan (ed.): Brand Whitlock, Diary, October 23, 1914. In: The Letters and Journal of Brand Whitlock, Vol. II, New York 1936, p. 58.

- ↑ Simoens, Tom: Warfare 1914-1918 (Belgium) , in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War, ed. by Ute Daniel, Peter Gatrell, Oliver Janz, Heather Jones, Jennifer Keene, Alan Kramer, and Bill Nasson, issued by Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin 2014-10-08. DOI: 10.15463/ie1418.10272.

- ↑ De Backer, Franz: Longinus, Arnhem 1934, pp. 26-27.

- ↑ De Vos, Luc: De Eerste Wereldoorlog [The First World War], Leuven 2011, p. 58.

- ↑ Christens, Ria / De Clercq, Karel: Frontleven 14/18. Het dagelijks leven van de Belgische soldaat aan de IJzer (Living at the front 14/18. Daily life of Belgian soldiers on the Yser River], Tielt 1987, p. 22.

- ↑ Olbrechts, Raymond: La population. In: Mahaim, Ernest: La Belgique restaurée: étude sociologique, Brussels 1926, pp. 3-66.

- ↑ Van Ypersele, Laurence: Trois volontaires de guerre dans les geôles allemandes, 1914-1918. Expériences et émotions, Guerres mondiales et conflits contemporains, Paris 2017/4, no. 268, pp. 135-156, figure p. 135.

- ↑ Amara, Michaël: Les Belges à l’épreuve de l’exil. Les réfugiés belges de la Première Guerre Mondiale en France, au Royaume-Uni et aux Pays-Bas, Brussels 2008, pp. 299-300.

- ↑ Brosens, Griet: Congo aan den Yzer: de 32 Congolese soldaten van het Belgisch leger in de Eerste Wereldoorlog, Antwerp 2013.

- ↑ Vanthemsche, Guy (ed.): Le Congo pendant la Première Guerre Mondiale. Les rapports du ministre des Colonies Jules Renkin au roi Albert Ier 1914-1918, Brussels 2009, p. 182.

- ↑ Simoens, Tom: De chaos van het slagveld. Het Belgisch leger in de loopgraven 1914-1918 [The Chaos of the Battlefield: The Belgian Army in the Trenches 1914-1918], Antwerp 2016.

- ↑ Van Den Dungen, Pierre: Press/Journalism (Belgium), in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War, ed. by Ute Daniel, Peter Gatrell, Oliver Janz, Heather Jones, Jennifer Keene, Alan Kramer, and Bill Nasson, issued by Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin 2014-10-08. DOI: 10.15463/ie1418.10341.

- ↑ Spijkerman, Rose: Between Acceptance and Refusal - Soldiers' Attitudes Towards War (Belgium), in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War, ed. by Ute Daniel, Peter Gatrell, Oliver Janz, Heather Jones, Jennifer Keene, Alan Kramer, and Bill Nasson, issued by Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin 2017-12-21. DOI: 10.15463/ie1418.11207.

- ↑ Roolf, Christoph: Generalgouvernement Belgien, in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War, ed. by Ute Daniel, Peter Gatrell, Oliver Janz, Heather Jones, Jennifer Keene, Alan Kramer, and Bill Nasson, issued by Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin 2015-04-23. DOI: 10.15463/ie1418.10621.

- ↑ Wegner, Larissa: Rear Area on the Western Front, in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War, ed. by Ute Daniel, Peter Gatrell, Oliver Janz, Heather Jones, Jennifer Keene, Alan Kramer, and Bill Nasson, issued by Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin 2016-02-12. DOI: 10.15463/ie1418.10826.

- ↑ De Schaepdrijver, Sophie: Marinegebiet, in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War, ed. by Ute Daniel, Peter Gatrell, Oliver Janz, Heather Jones, Jennifer Keene, Alan Kramer, and Bill Nasson, issued by Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin 2015-11-09. DOI: 10.15463/ie1418.10763.

- ↑ Amara, Michaël: Comité National de Secours et d'Alimentation, in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War, ed. by Ute Daniel, Peter Gatrell, Oliver Janz, Heather Jones, Jennifer Keene, Alan Kramer, and Bill Nasson, issued by Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin 2017-02-09. DOI: 10.15463/ie1418.11049.

- ↑ Shafer, Robert: Hoover, Herbert, in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War, ed. by Ute Daniel, Peter Gatrell, Oliver Janz, Heather Jones, Jennifer Keene, Alan Kramer, and Bill Nasson, issued by Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin 2015-03-16. DOI: 10.15463/ie1418.10578

- ↑ Little, Branden: Commission for Relief in Belgium (CRB) , in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War, ed. by Ute Daniel, Peter Gatrell, Oliver Janz, Heather Jones, Jennifer Keene, Alan Kramer, and Bill Nasson, issued by Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin 2014-10-08. DOI: 10.15463/ie1418.10071.

- ↑ Amara, Michaël / Roland, Hubert (eds.): Gouverner en Belgique occupée. Oscar von der Lancken-Wakenitz – Rapports d’activité 1915-1918. Édition critique, Brussels and Frankfurt 2004, p. 217.

- ↑ De Schaepdrijver, Sophie: Patriotic Distance, in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War, ed. by Ute Daniel, Peter Gatrell, Oliver Janz, Heather Jones, Jennifer Keene, Alan Kramer, and Bill Nasson, issued by Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin 2015-10-20. DOI: 10.15463/ie1418.10746.

- ↑ Nath, Giselle: Brood willen we hebben! Honger, sociale politiek en protest tijdens de Eerste Wereldoorlog in België [We Want Bread! Hunger, Social Politics, and Protest in First World War Belgium], Antwerp 2013, p. 187.

- ↑ Courtois, Luc: Mercier, Désiré Joseph (Version 1.1), in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War, ed. by Ute Daniel, Peter Gatrell, Oliver Janz, Heather Jones, Jennifer Keene, Alan Kramer, and Bill Nasson, issued by Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin 2017-11-15. DOI: 10.15463/ie1418.10207/1.1.

- ↑ De Schaepdrijver, Sophie / Debruyne, Emmanuel: Sursum Corda: The Underground Press in Occupied Belgium, 1914-1918, in: First World War Studies 4/1 (March 2013), pp. 23-38.

- ↑ Vanneste, Alex: Le premier “Rideau de fer”? La clôture electrisée à la frontière belgo-hollandaise pendant la Première Guerre Mondiale, in: Bulletin de Dexia Banque 54/214 (2000), pp. 39-82, figure p. 78.

- ↑ Pickles, Katie: Cavell, Edith Louisa (Version 1.1), in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War, ed. by Ute Daniel, Peter Gatrell, Oliver Janz, Heather Jones, Jennifer Keene, Alan Kramer, and Bill Nasson, issued by Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin 2017-01-24. DOI: 10.15463/ie1418.10214/1.1.

- ↑ Debruyne, Emmanuel: Le réseau Cavell: des femmes et des hommes en résistance, Brussels 2016; figure pp. 73-74.

- ↑ Debruyne, Emmanuel: Espionage, in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War, ed. by Ute Daniel, Peter Gatrell, Oliver Janz, Heather Jones, Jennifer Keene, Alan Kramer, and Bill Nasson, issued by Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin 2014-10-08. DOI: 10.15463/ie1418.10317.

- ↑ De Schaepdrijver, Sophie: Gabrielle Petit: The Death and Life of a Female Spy in the First World War, London 2015, p. 74.

- ↑ Proctor, Tammy M.: Female Intelligence: Women and Espionage in the First World War, New York 2003, p. 79.

- ↑ Connolly, James E.: Collaboration (Belgium and France), in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War, ed. by Ute Daniel, Peter Gatrell, Oliver Janz, Heather Jones, Jennifer Keene, Alan Kramer, and Bill Nasson, issued by Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin 2016-01-18. DOI: 10.15463/ie1418.10808.

- ↑ Tilly, Pierre / Deloge, Pascal: Milieux économiques belges et stratégie du moindre mal 1914-1918, in: Entreprises et histoire 68 (September 2012), pp. 11-27, quote on p. 26.

- ↑ Undated statement (presumably 1916). Haag, Henri: Le comte Charles de Broqueville, Ministre d’État, et les luttes pour le pouvoir (1910-1940), vol. 1, Louvain-la-Neuve-Brussels 1990, p. 327.

- ↑ Bost, Mélanie: Exercer la justice en zone occupée: l’expérience des magistrats belges, in: La bataille de Charleroi, 100 ans après. Actes de colloque. Charleroi, 22 et 23 août 2014, Brussels 2014, pp. 197-212.

- ↑ The title of a G.K. Chesterton article of Spring of 1915; reprint in The New York Times Current History 2/1 (April 1915), pp. 129-130.

- ↑ Edwards, Marvin L.: Stresemann and the Greater Germany 1914-1918, New York 1963, p. 41.

- ↑ Thiel, Jens / Westerhoff, Christian: Forced Labour, in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War, ed. by Ute Daniel, Peter Gatrell, Oliver Janz, Heather Jones, Jennifer Keene, Alan Kramer, and Bill Nasson, issued by Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin 2014-10-08. DOI: 10.15463/ie1418.10380.

- ↑ Bischoff, Sebastian: Kriegsziel Belgien. Annexionsdebatten und nationale Feindbilder in der deutschen Öffentlichkeit, 1914-1918, Münster and New York 2018, p. 220.

- ↑ Dolderer, Winfried: Deutscher Imperialismus und belgischer Nationalitätenkonflikt : Die Rezeption der Flamenfrage in der deutschen Offentlichkeit und deutsch-flämische Kontakte 1890-1920, Melsungen 1989, p. 132.

- ↑ Bost, Mélanie / Rezsöhazy, Élise: À contre-courant : les agents du contre-espionage allemand en Belgique occupée durant la Première Guerre Mondiale, in: Connolly, James et al. (eds.): En territoire ennemi. Expériences d’occupation, transferts, héritages (1914-1949), Villeneuve d’Ascq 2017, pp. 41-52, quote on p. 46.

- ↑ Benvindo, Bruno: Des Hommes En Guerre. Les Soldats Belges Entre Ténacité Et Désillusion, 1914-1918, Brussels 2005.

- ↑ Decock, Pierre: La Dame Blanche, in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War, ed. by Ute Daniel, Peter Gatrell, Oliver Janz, Heather Jones, Jennifer Keene, Alan Kramer, and Bill Nasson, issued by Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin 2014-10-08. DOI: 10.15463/ie1418.10241.

- ↑ Engelen, Leen / Sterckx, Marjan: An ephemeral open-air sculpture museum: ten temporary monuments for the festive return of the Belgian royal family to Brussels, November 1918, in: Sculpture Journal 26/3 (1917), pp. 321-348.

- ↑ Delcorps, Vincent: Loppem Coup, in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War, ed. by Ute Daniel, Peter Gatrell, Oliver Janz, Heather Jones, Jennifer Keene, Alan Kramer, and Bill Nasson, issued by Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin 2014-10-08. DOI: 10.15463/ie1418.10266.

- ↑ Debruyne, Emmanuel: Femmes à boches. Occupation du corps féminin, dans la France et la Belgique de la Grande Guerre, Paris 2018.

- ↑ Majerus, Benoît: War Losses (Belgium), in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War, ed. by Ute Daniel, Peter Gatrell, Oliver Janz, Heather Jones, Jennifer Keene, Alan Kramer, and Bill Nasson, issued by Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin 2016-01-25. DOI: 10.15463/ie1418.10812.

- ↑ Sharp, Alan: The Paris Peace Conference and its Consequences, in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War, ed. by Ute Daniel, Peter Gatrell, Oliver Janz, Heather Jones, Jennifer Keene, Alan Kramer, and Bill Nasson, issued by Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin 2014-10-08. DOI: 10.15463/ie1418.10149.

- ↑ Marks, Sally: Innocent Abroad: Belgium at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919, Chapel Hill 1981, p. 199.

- ↑ Jacquemin, Madeleine: Les forges de Clabecq, une entreprise belge sous l’occupation, in Eck, Jean-François / Heuclin, Jean (eds.): Les bassins industriels des terres occupées 1914-1918: des opérations militaires à la reconstruction, Valenciennes 2016, pp. 347-363, specifically pp. 357-358.

- ↑ De Schaepdrijver, Sophie: ‘That Theory of Races’: Henri Pirenne on the Unfinished Business of the Great War, in: Revue Belge d’Histoire Contemporaine 41/3-4 (2011), pp. 533-552, p. 533.

- ↑ De Schaepdrijver, Sophie: Literature (Belgium), in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War, ed. by Ute Daniel, Peter Gatrell, Oliver Janz, Heather Jones, Jennifer Keene, Alan Kramer, and Bill Nasson, issued by Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin 2014-10-08. DOI: 10.15463/ie1418.10449.

Selected Bibliography

- Bitsch, Marie-Thérèse: La Belgique entre la France et l'Allemagne, 1905-1914, Paris 1994: Publications de la Sorbonne.

- Bost, Mélanie / Colignon, Alain: La Wallonie dans la Grande Guerre: 1914-1918, Brussels 2016: La Renaissance du Livre.

- Debruyne, Emmanuel / Paternostre, Jehanne: La résistance au quotidien, 1914-1918. Témoignages inédits, Brussels 2009: Racine.

- Debruyne, Emmanuel / van Ypersele, Laurence: Je serai fusillé demain. Les dernières lettres des patriotes belges et français fusillés par l'occupant, 1914-1918, Brussels 2011: Racine.

- De Kerchove De Denterghem, Charles, Heuclin, Jean / Terrier, Didier (eds.): L'industrie belge pendant l'occupation allemande, Valenciennes 2017: Presses Universitaires de Valenciennes.

- De Schaepdrijver, Sophie / Proctor, Tammy M.: An English governess in the Great War. The secret Brussels diary of Mary Thorp, New York 2017: Oxford University Press.

- Gubin, Éliane: Choisir l'histoire des femmes, Brussels 2007: Editions de l'université de Bruxelles.

- Jaumain, Serge / Amara, Michaël / Majerus, Benoît et al. (eds.): Une 'guerre totale'? La Belgique dans la Première Guerre mondiale. Nouvelles tendances de la recherche historique, Brussels 2005: Archives générales du Royaume.

- Loriaux, Florence: 1914-1918. Le chômeur entre suspicion et héroïsme, in: Loriaux, Florence (ed.): Le chômeur suspect. Histoire d'une stigmatisation, Brussels 2015: CRISP, pp. 75-94.

- Maréchal, Christine / Schloss, Claudine: 1914-1918. Vivre la guerre à Liège et en Wallonie, Liège 2014: Éditions du Perron.

- Meseberg-Haubold, Ilse: Der Widerstand Kardinal Merciers gegen die deutsche Besetzung Belgiens, 1914-1918. Ein Beitrag zur politischen Rolle des Katholizismus im Ersten Weltkrieg, Frankfurt a. M. 1982: Lang.

- Pirenne, Henri: Belgium and the First World War, Wesley Chapel 2014: The Brabant Press.

- Pluvinage, Gonzague (ed.): 1914-1918 Villes en guerre – Cities at war, Cahiers bruxellois, revue d'histoire urbaine, Brussels 2014: Archives de la Ville de Bruxelles.

- Roland, Hubert: La 'colonie' littéraire allemande en Belgique, 1914-1918, Brussels 2003: Labor.

- Scholliers, Peter / Daelemans, Frank: Standards of living and standards of health in wartime Belgium, in: Wall, Richard / Winter, Jay (eds.): The upheaval of war. Family, work, and welfare in Europe, 1914-1918, Cambridge; New York 1988: Cambridge University Press, pp. 139-157.

- Spijkerman, Rose: ‘The Cross, naturally’. Decorations in the Belgian Army and their effect on emotions, behaviour and the self, 1914–1918, in: War in History, 2018.

- Thielemans, Marie-Rose (ed.): Albert Ier. Carnets et correspondance de guerre 1914-1918, Paris 1991: Duculot.

- Thiel, Jens: 'Menschenbassin Belgien'. Anwerbung, Deportation und Zwangsarbeit im Ersten Weltkrieg, Essen 2007: Klartext Verlag.

- van Ypersele, Laurence: Le roi Albert. Histoire d'un mythe, Ottignies 1995: Quorum.

- van Ypersele, Laurence / Debruyne, Emmanuel: De la guerre de l'ombre aux ombres de la guerre. L'espionnage en Belgique durant la guerre de 1914-1918, histoire et mémoire, Brussels 2004: Éditions Labor.

- Verstraete, Pieter / Van Everbroeck, Christine: Le silence mutilé. Les soldats invalides belges de la Grande Guerre, Namur 2014: Presses universitaires de Namur.

- Vrints, Antoon: Beyond victimization. Contentious food politics in Belgium during World War I, in: European History Quarterly 45/1, 2015, pp. 83-107.

- Wende, Frank: Die belgische Frage in der deutschen Politik des Ersten Weltkrieges, Hamburg 1969: Eckart Bohme.

- Wils, Lode: Flamenpolitik en aktivisme. Vlaanderen tegenover België in de eerste wereldoorlog (Flamenpolitik and activism. Flanders against Belgium in World War One), Leuven 1974: Davidsfonds.