Forming the CRB↑

Established in October 1914 to import food into and ensure its distribution within German-occupied Belgium, the Commission for Relief in Belgium (CRB) quickly became one of the foremost international relief organizations in the First World War era. It had no equal in the scope of its responsibility to feed an entire nation of nearly 7.3 million. Its necessity arose from German and British war policies. The German invasion of Belgium destroyed or commandeered many agricultural stockpiles and livestock; Berlin insisted that it held no legal responsibility to feed civilians under its harsh occupation regime. Britain used its powerful navy to erect a strict blockade to deny the importation of war materials, including food, to Belgium, in order to prevent their confiscation by German forces. Yet as the most densely populated and industrialized country in Europe, Belgium depended on agricultural imports to sustain its population. Ordinarily Belgians purchased 78 percent of their dietary staple, wheat, from abroad, along with many other foodstuffs, but the war immediately stopped all imports and threatened the people of Belgium with starvation.

The CRB was conceived in meetings between Belgian representatives, the U.S. minister to Belgium, Brand Whitlock (1869-1934), his Spanish counterpart, Rodrigo Marquis de Villalobar (1864-1926), the U.S. ambassador to Britain, Walter Hines Page (1855-1918), and an American businessman and mining engineer, Herbert C. Hoover (1874-1964), who became the CRB’s indomitable director. Its existence depended upon the belligerent governments of Britain, Germany, and France permitting a newly improvised, neutral humanitarian agency to import food through the blockade and supervise its delivery to Belgian communities (later expanded, in April 1915, to nearly 2 million inhabitants in German-occupied northern France). Ironically, a rigid trench system formed along the Western Front aided immeasurably in the development of a viable relief system because conditions behind German lines were relatively stable. Empowered with special diplomatic status that enabled it to freely transit the rival warring coalitions’ lines, the CRB became, in the words of a British diplomat, “a piratical state organized for benevolence.”[1]

Securing the additional acceptance of the Belgian government in exile, the neutral government of The Netherlands (which allowed the use of Rotterdam as the port of importation), Spain and the United States (which served as patrons of the CRB), required ingenuity to protect the relief operations from the vicissitudes of war that regularly threatened to derail the program. Obtaining sufficient subventions from Belgium, Britain, France, and the United States to purchase and transport almost 1 billion dollars’ worth of foodstuffs from global sources between 1914 and 1919 likewise proved exceptionally laborious and vulnerable to the changing contours of Allied finances, strategy, and policy.

Orchestrating Relief↑

The CRB operated on a commercial basis with administrative costs that totaled a mere 0.43 percent. Whereas it sold food to Belgians who could afford to pay in order to provision those who were wholly dependent on charity, rising destitution triggered by industrial paralysis in occupied Belgium and France meant that ever fewer could purchase food. Worsening economic conditions continually increased the CRB’s financial burdens associated with food procurement. Britain’s prohibition against warehousing more than a meager supply of food in Belgium and France to limit the damage if Germany seized the stockpiles created additional challenges. The lack of financial and food reserves in conjunction with cargo losses to submarines and sea mines meant that the CRB could not offer any genuine assurances that it could prevent famine in the occupied territories. Its officials, mainly Americans, nevertheless eschewed compensation and risked their lives by transiting the war zones to ensure the delivery of food and accomplish their primary objective: avert starvation. While famine never erupted thanks to the CRB’s exertions, hunger was pervasive, and malnutrition-linked diseases and mortality rates soared by war’s end.

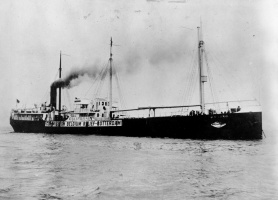

CRB offices in London, Rotterdam, and New York orchestrated the global humanitarian operations that sustained occupied Belgium and France. Agents located in port cities stretching from Buenos Aires to Bergen, Rangoon to San Francisco, superintended the shipments of grains, flour, lentils, peas, beans, rice, animal fats, and forage on a chartered fleet of CRB-flagged vessels. A constant flow of private contributions including in-kind services, money, food, and clothing to the CRB and the Belgian government illustrated the popularity of Belgian relief in the Anglophone world and among the Belgian diaspora that maintained a network of approximately 2,000 committees consisting of tens of thousands of volunteers. The U.S. government, though neutral at war’s outset, strongly supported the CRB’s work. Its opposition to submarine warfare and the deportation of Belgians to German labor camps drew inspiration from CRB protests, and President Woodrow Wilson’s (1856-1924) war message in 1917 stressed fighting “for the rights and liberties of small nations.”[2] Belgian relief had helped to unravel American neutrality.

From its headquarters in occupied Brussels, the CRB coordinated the receipt of more than 2,300 overseas and cross-Channel ships’ cargoes from Rotterdam via rail and canal, averaging 100,000 tons of bulk foods per month for almost five years, as well as their distribution across occupied Belgium and France. American “delegates” possessed legal immunities and proved so popular among the beleaguered populations that German officials resented their presence for emboldening passive resistance.

However, with its skeletal staff of less than 100 Americans volunteering at any one time between 1914 and 1917, the CRB could not have independently conducted relief without host-nation counterparts in the Comité National de Secours et d’Alimentation led by the Belgian financier Emile Francqui (1863-1935) and the Comité d’Alimentation du Nord de la France. These indigenous organizations expanded already existing charitable distribution channels within nearly 10,000 regional and local committees and mobilized a humanitarian “army” of more than 70,000 Belgians and French civilians who distributed the CRB-imported food. They made invaluable contributions to the executive, administrative, and distributive apparatus of relief.

When American personnel were obligated to withdraw from German-held territory upon the U.S. declaration of war on Germany in April 1917, they were replaced by Spanish and Dutch officials who labored until the Armistice in 1918. Despite the exertions of the Belgians, French, Spanish, and Dutch, the American CRB under Hoover’s direction received the lion’s share of the credit for this life-sustaining enterprise.

Postwar Operations and Legacy↑

After the Armistice, American personnel returned to the newly liberated Belgian and French territories and coordinated emergency aid services with local assistance. The CRB concurrently diversified its operations to include food sales to Germany, with its last shipment occurring in August 1919. In its fifth and final year, the CRB withdrew, and Belgium and France assumed responsibility for feeding their emancipated peoples. Belgian universities and educational foundations received the CRB’s residual funds as gifts.

Hoover’s reputation as a resourceful, combative, and dynamic administrator, combined with the CRB’s record of accomplishment, formed the basis for enlarged American aid to postwar Europe via the American Relief Administration (ARA) that concluded its continent-wide feeding operations in 1924. Thus, Hoover-directed American food relief in the First World War era encompassed a period of ten years, from 1914 to 1924, and expended 5.2 billion dollars for relief materials, saving millions of lives.

The CRB undeniably awakened the world to the possibilities of receiving humanitarian aid in wartime; with its success, moreover, came the expectation that relief should be forthcoming. Many countries solicited American aid during and after the war because of what the CRB had done for Belgium, although few people genuinely understood how improbable was its success given the extraordinary challenges the war continually presented.

Branden Little, Weber State University

Section Editor: Emmanuel Debruyne

Notes

Selected Bibliography

- Gay, George I.: The Commission for Relief in Belgium. Statistical review of relief operations. Five years, November 1, 1914, to August 31, 1919 and to final liquidation, Stanford 1925: Stanford University Press.

- Hertog, Johan den: The Commission for Relief in Belgium and the political diplomatic history of the First World War, in: Diplomacy & Statecraft 21/4, 2010, pp. 593-613.

- Kittredge, Tracy Barrett: The history of the Commission for Relief in Belgium, 1914-1917, London 1919: unpublished manuscript.

- Little, Branden: Humanitarian relief in Europe and the analogue of war, 1914-1918, in: Neiberg, Michael S. / Keene, Jennifer D. (eds.): Finding common ground. New directions in First World War Studies, Leiden 2010: Brill, pp. 139-158.

- Nash, George H.: The life of Herbert Hoover. The humanitarian, 1914-1917, New York 1988: W.W. Norton.