Introduction↑

On the eve of the First World War, Brussels and its suburbs had around 790,000 inhabitants separated into sixteen autonomous municipalities, each headed by a mayor. The city was the political and financial heart of the country and had developed and extended remarkably since the creation of Belgium. A series of works had considerably changed its shape; it had been modernised, beautified, improved, and turned into an attractive centre both for Belgians and foreigners.

The Outbreak of the War and the Beginning of the Occupation↑

In a sense, both fear and excitement pervaded Brussels in the days preceding the German attack on 4 August 1914. Fear drew people to the banks to exchange their bills for gold and to the stores to buy food supplies, thereby contributing to scarcity and price increases. The same fear prompted others to harass the German inhabitants of the capital. The declaration of war and the discourse of the King at Parliament on 4 August triggered unprecedented patriotic fervour. The progression of the German army soon put Brussels in a dangerous position, and on 5 August, Albert I, King of the Belgians (1875-1934) and the government left the city. As a result, the local authorities stood face-to-face with the Germans who entered the capital on 20 August. In order to avoid reprisals against civilians, liberal Mayor Adolphe Max (1869-1939), who headed the city's government from 1909 until his death, gave orders to hand in all arms, fill the trenches, destroy the barricades, and to dissolve the civic guard (a militia created in 1830 to maintain social order and mobilised on 4 August).

On 20 August 1914, German troops crossed the city in an endless parade that would be remembered for many years to come, marking the beginning of a long occupation. The relationships between local authorities and occupying forces were strained. Indeed, the Belgian authorities were compelled to work with the occupier, who repeatedly interfered in the municipalities’ management. They also intervened increasingly in issues related to food, work, and education. Moreover, the German General Governor Moritz von Bissing (1844–1917) lived in the capital and many ministries and administrative buildings were confiscated for the Germans’ use. Their presence created a series of housing problems, since barracks and private lodgings were appropriated to accommodate around 10,000 German soldiers in the capital. Moreover, the German occupiers imposed burdensome war contributions and requisitioned numerous goods.

Daily Life during the Occupation↑

The Mayor was arrested on 26 September 1914 for suspending the payment of war contributions. Other municipal authorities met the same fate. For the population, the food supply became a pressing issue. To avoid famine, Brussels created a National Relief and Food Committee in 1914. Soon they joined the Commission for Relief in Belgium, which ensured the food imports for the country. In the city, hunger and scarcity reached all social classes. The National Committee established a relief programme according to the level of poverty, though “patriotic loyalty” was equally necessary to benefit from the programme. Survival strategies were set up, such as cultivating plots of land in the city. Misery also compelled some people to leave Belgium to work in Germany and a number of women resorted to regular or occasional prostitution.

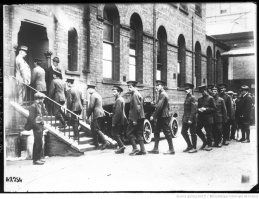

The population suffered from the occupation: moving was difficult, if not impossible and the press was censored. Wanting to encourage work in Germany, the occupier targeted jobless men. In response, the municipalities set up strategies to help Belgian workers remain in Brussels, such as the building and maintenance of roads and parks. Yet they had little freedom due to financial difficulties. In the fall of 1916, compulsory work was established. The decision implied seeking out unemployed men, by coercing businesses and pressuring municipal administrations to turn over jobless men. In other words, the occupier established a climate of fear and terror. The measure would be withdrawn later, but in the early months of 1918, more than 100,000 Belgian workers were deported to Germany. The occupier also tried to have his say in the local organisation, only negotiating with the Mayor of Brussels, who communicated the orders to the other municipalities.

Flamenpolitik↑

In order to weaken the country, the Germans sought to create an alliance with the Flemish movement through the so-called Flamenpolitik. All the municipalities (except Ixelles) were declared Flemish. In the plan for administrative separation, Brussels was proclaimed the capital of Flanders. Still, the capital most notably resisted through underground press. Despite fierce enemy pressure, most of the seventy-six underground newspapers were produced in Brussels.

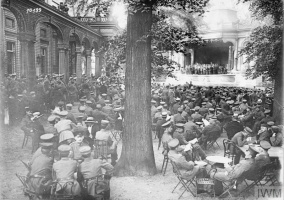

Brussels was also symbolically a place of repression. The rooms of the Senate were used as a military court. A total of thirty-five patriots were executed at the Tir National in Schaerbeek. In a way, institutions, such as the Church, also set up resistance strategies. In Brussels as well as in other places, a form of cultural life continued to exist, if only for the benefit of the German soldiers. Concerts were organized and theatres featured German plays. A certain level of restraint formed the implicit resistance through moderation, such as refusing to have fun or to participate in futile activities, and of ocurse zwanze or humour bruxellois, a type of humour specific to Brussels. Humour was widely used to mock the occupier and denounce war profiteers.

In reaction to the February 1918 release of two Flemish activists (people who considered the German occupation as an opportunity for the Flemish agenda), the Belgian judiciary went on strike. The strike compelled the Germans to create their own courts. For the Belgian judiciary, this strike also symbolized, belatedly, their unwillingness to give in to the occupiers.

The Last Months of the War↑

After the last large Allied offensive in September 1918, refugees fleeing from the combat zones flocked to Brussels. Their exact number remains unknown, though some sources mention more than 100,000 refugees. The situation was chaotic, with sanitary conditions worsening and scarcity increasing still further. The capital had a peculiar liberation. A Soldatenrat was created on 10 November 1918. The soldiers rebelled against their superiors and unsuccessfully tried to fraternize with the local population. The last days were marked by violence, with the people retaliating against war profiteers and women suspected of having had sexual relations with Germans. Added to the brutality of the German soldiers, the events resulted in a still unknown number of victims. Even after the last German soldiers left Brussels on 16 November, there was pilfering, cases of ammunition stocks exploding, and further attacks on war profiteers or women suspected of having had relations with Germans. On 17 November, the population triumphantly welcomed back Adolphe Max, who had been released. He had benefited from the general chaos following the capitulation of Germany and had slipped back into Belgium. Order was re-established on 22 November 1918, when the Royal Family made their joyous entry into the streets of the capital.

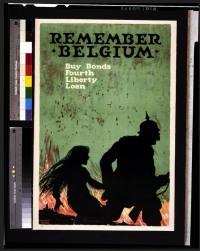

An Exceptional War Remembrance↑

The memory of the war left its mark on Brussels: more than 300 street names are directly or indirectly linked to the war. Many monuments were built to honour soldiers and civilians, and the memory of this first occupation pervaded the capital during the inter-war period.

Chantal Kesteloot, CegeSoma

Section Editor: Emmanuel Debruyne

Selected Bibliography

- De Schaepdrijver, Sophie; Debruyne, Emmanuel: Sursum Corda. The underground press in occupied Belgium, 1914-1918, in: First World War Studies 4/1, 2013, pp. 23-38.

- Gille, Louis / Ooms, Alphonse / Delandsheere, Paul: Cinquante mois d'occupation allemande, volume 1-2, Brussels 1919: A. Dewit.

- Giron, Marguerite: Journal d'une bourgeoise. 1914-1918, Brussels 2015: Editions de l'Université.

- Jaumain, Serge / Piette, Valérie: Bruxelles en 14-18. La guerre au quotidien, Les cahiers de La Fonderie, Brussels 2005: La Fonderie.

- Jaumain, Serge / Piette, Valérie / Pluvinage, Gonzague: Bruxelles 14-18. Au jour le jour, une ville en guerre, Brussels 2005: Musée de la Ville de Bruxelles.

- Kesteloot, Chantal: Un interlocuteur mal connu. La Conférence des Bourgmestres de Bruxelles à l'heure des occupations, in: Cercle d'histoire de Bruxelles 113, 2011, pp. 3-8.

- Lancken, Oscar von der / Amara, Michaël / Roland, Hubert (eds.): Gouverner en Belgique occupée. Oscar von der Lancken-Wakenitz. Rapports d'activité 1915-1918, Brussels 2004: P.I.E.-Peter Lang.

- Majerus, Benoît: Occupations et logiques policières. La police bruxelloise en 1914-1918 et 1940-1945, Brussels 2007: Académie royale de Belgique, Classe des Lettres.

- Majerus, Benoît: 'L'âme de la résistance sort des pavés mêmes?' Quelques réflexions sur la manière dont les Bruxellois sont entrés en guerre (fin juillet 1914 - mi-août 1914), in: Jaumain, Serge / Amara, Michaël; Majerus, Benoît et al. (eds.): Une guerre totale? La Belgique dans la Première Guerre mondiale. Nouvelles tendances de la recherche historique, Brussels 2005: Archives générales du Royaume.

- Max, Paul / Majerus, Benoît / Soupart, Sven (eds.): Journal de guerre de Paul Max. Notes d'un Bruxellois pendant l'occupation (1914-1918), Brussels 2006: Archives de la Ville de Bruxelles.

- Sieben, Luc: De novemberdagen van 1918 te Brussel. Revolutie en ordehandhaving (The November days of 1918 in Brussels. Revolution and public order management), in: Lefèvre, Patrick / Gryse, Piet de (eds.): Van Brialmont tot de Westeuropese Unie. Bijdragen in de militaire geschiedenis aangeboden aan Albert Duchesne, Jean Lorette en Jean-Léon Charles, Brussels 1988: Koninklijk Legermuseum, pp. 155-176.

- van Ypersele, Laurence / Kesteloot, Chantal / Debruyne, Emmanuel: Brussels. Memory and war (1914-2014), Waterloo 2014: Renaissance du Livre.

- Whitlock, Brand: La Belgique sous l'occupation Allemande; memoires du Ministre d'Amerique a Bruxelles, Paris 1922: Berger-Levrault.