The Flemish Movement Instrumentalised↑

The Flamenpolitik consisted of the German policy of instrumentalising the Flemish movement in order to ensure German influence in Belgium in both the short- and the long-run. The Germans wanted to break Belgian anti-German patriotism by stimulating internal tensions. To achieve this goal the Germans wished to alienate the Flemish movement from the Belgian cause and sense of nationhood by stimulating the Dutch language and culture in Belgium. Germany wanted to make use of the occupation to impose itself as the natural and lasting protector of the Flemings. If Germany were to be forced to give up Belgium, it still would be able to exercise great influence through its new pro-German Flemish nationalist allies. In a broader perspective, Flamenpolitik aimed at maximising German influence in the Low Countries as a whole, and even beyond. From the very beginning it had a particular pan-Dutch flavour, since it was meant to strengthen sympathy for Germany in the neutral Kingdom of the Netherlands. The prospect of a Greater Netherlands or at least a weakened Belgium was used to try to lure the Northern Netherlands into the German zone of influence. Similarly, the pan-Dutch card opened good prospects for German advancement in French Flanders and Southern Africa.

Before the First World War, the German government did not intervene in internal Belgian affairs, since it had been quite happy during the thirty-year conservative rule of the Catholic party, which kept its distance from republican France. However, in German imperialist and nationalist interest groups like the Alldeutscher Verband, the Flottenverein and Kolonialverein, the necessity of integrating the Low Countries in the German sphere had been vividly discussed for decades on both völkische and geopolitical grounds. When it became clear that Belgium resisted the German invasion in August 1914, a number of plans what to do with the conquered kingdom – now generally perceived as “artificial” since it lacked völkische coherence – saw the light of day. These plans strongly diverged on the methods – (partial) annexation or the creation of satellite state(s) – but shared the common goal of lasting German dominance in Belgium. Each of the plans reflected pre-war thinking. The presumed ethnic rift between Flemings and Walloons was a major topic in most of these plans.

The Flemish Movement Divided↑

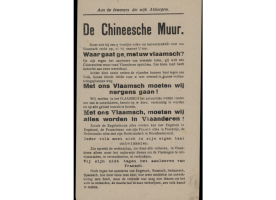

Even before the Dutch-speaking provinces were occupied, Flamenpolitik was initiated at the very highest level in Germany. Acting as a strong force, Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg (1856-1921) ordered the German administration in Brussels to stimulate the Flemish movement on 2 September 1914. By the winter of 1914-15 a concrete program had been developed: support for the Dutch language with, as its pièce-de-résistance, the Dutchification of the state University of Ghent (the main pre-war demand of the Flemish Movement), the intensification of relations with Holland and administrative separation between Flanders and Wallonia (an idea almost absent in the Flemish Movement before 1914). This program was to be cautiously but systematically elaborated by the governor-generals of occupied Belgium. In 1916, Ghent University was re-opened with Dutch as the language of instruction. In 1917, a puppet parliament, the Raad van Vlaanderen (Council of Flanders), was created, and administrative separation was introduced. The military authorities in the Etappengebiet followed a more radical, overtly anti-Belgian policy which led to persistent conflicts with the General-Gouvernement. As both the authorities in the General-Gouvernement and Etappengebiet wanted to weaken or destroy Belgium, the difference was only tactical. In order to be successful, the governor-generals knew that they had to operate cautiously given the strength of Belgian nationalism and anti-German feelings.

Flamenpolitik did not divide the Belgian or even Flemish population as a whole, but managed to tear apart the Flemish movement. A minority of the adherents of the Flemish movement were willing to collaborate (the so-called activisme) with the result that the Flemish movement was permanently divided into a loyalist and an anti-Belgian wing. During the war, the effects of the Flamenpolitik on the ground might have remained meagre as it met popular resistance or indifference, however, in the longer run Flamenpolitik had a long lasting impact on Belgian history by stimulating the creation of anti-Belgian Flemish nationalism as a political current. Until the early 1920s the Weimar Republic discreetly continued its Flamenpolitik; the Nazis later reactivated it. During the Second World War, Adolf Hitler (1889-1945) ordered a new Flamenpolitik; with a living memory of the administrative chaos created as a result of the administrative separation during the First World War, the German authorities largely limited themselves to the release of Flemish – and not Walloon – prisoners of war and the massive nomination of Flemish nationalists in the Belgian administrations.

Antoon Vrints, Ghent University

Section Editor: Emmanuel Debruyne

Selected Bibliography

- Dolderer, Winfried: Deutscher Imperialismus und belgischer Nationalitätenkonflikt. Die Rezeption der Flamenfrage in der deutschen Öffentlichkeit und deutsch-flämische Kontakte 1890-1920, Melsungen 1989: Verlag Kasseler Forschungen zur Zeitgeschichte.

- Wils, Lode: Onverfranst, onverduitst? Flamenpolitik, activisme, frontbeweging (Not Frenchified, not Germanized? Flamenpolitik, activism, front movement), Kalmthout 2014: Uitgeverij Pelckmans.

- Yammine, Bruno: Drang nach Westen. De fundamenten van de Duitse flamenpolitik (1870-1914) (Drang nach Westen. The foundations of the German Flamenpolitik (1870-1914)) (1 ed.), Leuven 2011: Davidsfonds.