“Absolutely Blatant Hostility”↑

The German expressionist poet Gottfried Benn (1886-1956), who spent the war years in occupied Belgium as an army physician, later described the civilians as “full of absolutely blatant hostility.”[1] The sociologist Max Weber (1864-1920), writing in the summer of 1915, qualified German domination over Brussels as “eerie” (gespenstisch).[2] Several personal accounts by occupation administrators expressed a sense of isolation. Some suffered from this; others basked in the heady knowledge that they were detested and relished seeing people leave when they entered a concert hall or restaurant.

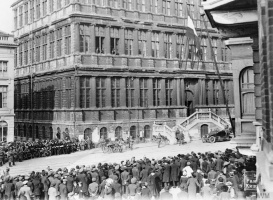

Such scenes were common. German, Belgian and neutral observers noted all kinds of enactments of distance. Occupiers and occupied even lived in different time zones: among themselves, civilians refused to acknowledge the transition to Central European time. Necessary cooperation was conducted, at least at first, at arm’s length: when emissaries of the Belgian food aid organisation first “met” with officials from the occupation regime, both parties sat in separate rooms. Old friendships froze: the playwright Alfred Hegenscheidt (1866-1964), a Belgian of German descent, regretfully instructed a dear friend, the Socialist journalist Gustav Mayer (1871-1948), now working for the occupation administration, not to call on him. Patriotic honour mandated the shunning of German-sponsored events. The May 1916 performance of Richard Wagner’s (1813-1883) Ring attracted virtually no Belgians, although Wagner had been all the rage in pre-war Belgium. Nor was such behaviour exclusive to the bourgeoisie. Although working-class people, in their quest for survival, were less able to afford the luxury of distance, they too judged behaviour. In the working-class areas of Ghent, women who sewed sandbags for the German trenches were shunned by their neighbours; and, in one brutal episode, inhabitants of the Brussels canal zone attacked a group of women who lamented the departure of a German regiment.

Diminishing Distance↑

As with so much else in this war, the year 1916 saw a shift. Until then, hopes of imminent liberation had stimulated immediate public engagement, even if only through gestures. Now that the end of the war had receded from sight, more and more civilians dismissed it as a parenthesis, and resumed living. Civilians no longer ostentatiously plugged their ears to German military bands. More and more people gave in to “German time,” though to keep up appearances they called it “clock-tower time.” Officials struck up friendships with writers and artists – especially in avant-garde circles. Enough Flemish militants were now willing to work with the occupying regime that the regime-created Flemish University of Ghent gained a semblance of normality.

Yet there was no essential breaching of “patriotic distance.” Rapprochements remained scarce, in part because of the regime’s intensified exploitation, including forced labour. German-friendly civilians were ostracised and had little influence on the wider society. One German official stated in 1919 that the occupation regime had not “even remotely broken the stubborn resistance of this people [and] its obstinate expectation of delivery.”[3]

Interpreting “Patriotic Distance”↑

After the war, “patriotic distance” was condemned as conformist posturing and as a refusal to accept common humanity. These criticisms had a point, but they failed to acknowledge that military occupation rendered rapprochements as problematic as colonial regimes did. “Patriotic distance” was, at heart, the enactment of a refusal to acknowledge the legitimacy of a regime based on conquest. It need not exclude reconciliation once such a regime ended. In 1916, the young Belgian saleswoman Gabrielle Petit (1893-1916), imprisoned for espionage, wrote to the German prison translator to say she was fond of him but could not be his friend while he was in “an army that I execrate.”[4] In a 1919 memoir, the German-Alsatian officer and novelist Otto Flake (1880-1963), who had worked at the censors’ office in Brussels, recalled his 1916 opinion that “patriotic distance” was the decent attitude to take, indeed “an honest and clean divide” that took into account both “the feelings of the vanquished” and “the presence of the victors.”[5]

To sum up, “patriotic distance” was a form of agency on the part of the conquered. Best approached through the cumulative study of many lowly sources, it merits attention – for the moral boundaries that it implied and performed (indeed its very belief in performative action as relevant) were part and parcel of the war’s cultural universe; and, like it, they had become incomprehensible ten years on.

Sophie De Schaepdrijver, Pennsylvania State University

Section Editor: Emmanuel Debruyne

Notes

- ↑ Benn, Gottfried: “Wie Miss Cavell erschossen wurde”, in: Benn, Gottfried: Gesammelte Werke, Vol. IV: Autobiographische und vermischte Schriften, edited by Dieter Wellershoff, Wiesbaden 1961 [1928], p. 197.

- ↑ Mommsen, Wolfgang: Max Weber und die Deutsche Politik 1890–1920, Tübingen 1974, p. 218.

- ↑ Waentig, Heinrich: Belgien, Halle 1919 (volume 2 of the second series of the Auslandsstudien der Universität Halle-Wittenberg), p. 18.

- ↑ Quoted in De Schaepdrijver, Sophie: Gabrielle Petit: The Death and Life of a Female Spy in the First World War, London 2015, p. 105.

- ↑ Flake, Otto: Das Logbuch, Gütersloh 1970 [1917], p. 195.

Selected Bibliography

- Benn, Gottfried: Wie Miss Cavell erschossen wurde (1928), in: Wellershoff, Dieter (ed.): Gesammelte Werke. Autobiographische und vermischte Schriften, volume 4, Wiesbaden 1961: Limes, pp. 194-201.

- De Schaepdrijver, Sophie: Bastion. Occupied Bruges in the First World War, Veurne 2015: Hannibal.

- De Schaepdrijver, Sophie: Populations under occupation, in: Winter, Jay (ed.): The Cambridge history of the First World War. Civil society, volume 3, 2013, pp. 476-504.

- De Schaepdrijver, Sophie; Debruyne, Emmanuel: Sursum Corda. The underground press in occupied Belgium, 1914-1918, in: First World War Studies 4/1, 2013, pp. 23-38.

- Roland, Hubert: La 'colonie' littéraire allemande en Belgique, 1914-1918, Brussels 2003: Labor.