Introduction↑

The “Imperial Government General in Belgium” (Kaiserliches Generalgouvernement in Belgien, GG Belgium for short) headed by the governor-general was established by the highest cabinet order of Wilhelm II, German Emperor (1859-1941) on 23 August 1914, after the German Army’s occupation of wide areas of Belgium (including the capital Brussels).

Territory and Legal Ground↑

Although the Germans occupied farther territories of the country – only the area around the Yser River remained free – GG Belgium did not include all Belgian territory, but rather the provinces of Liège, Luxembourg, Namur, eastern Hainaut, Brabant, Antwerp and Limburg as well as a few eastern municipalities of the province of East Flanders. Added to this were two French areas – one encompassing Givet and Fumay and the second around the town of Maubeuge in Northern France (the latter was only held until October 1916); both areas abut Belgian state territory. The provinces of East Flanders and West Flanders were part (definitively since the middle of December 1915) of the so-called “Etappengebiet” and the operation zone of the German troops in the west; they were administrated respectively by the High Command of the Fourth Army in Ghent and by the Marine Corps Flanders in Bruges. However, the orders and directions of the German governor-general in Brussels could of course be applied in the Etappengebiet and in the operation zone if the army officers there upheld them.

The legal ground for GG Belgium was laid by the Hague Conventions from 1899/1907 with their single provisions about the administration of occupied territories. The governor-general and his administration acted as substitutes for Albert I, King of the Belgians (1875-1934) and his cabinet of ministers (who had gone into exile in Le Havre in France) and controlled as a supervisory administration the Belgian ministries and local administrations (which continued working during the years of occupation). It is true that Belgian laws continued to be valid but they could be changed on the instruction of the governor-general.

Structure↑

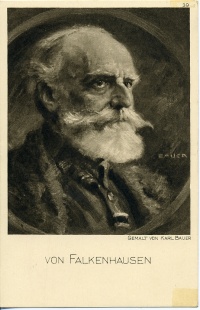

The governor-general – first Colmar Freiherr von der Goltz (1843-1916) who was succeeded by Moritz Freiherr von Bissing (1844-1917) from the end of November 1914 and (after Bissing’s death in April 1917) Ludwig Freiherr von Falkenhausen (1844-1936) – ruled with the help of occupation officers structured into a military administration and a civil administration. The “Government General,” headed by the governor-general, was responsible for the occupation troops and their actions, border control, the control of the movement of people, goods and all vehicles within the territory and the military police and administration of justice; the domestic administration and foreign affairs was the domain of the civil administration (Zivilverwaltung). At its head, with the title of Administration chief at the governor-general in Belgium (Verwaltungschef bei dem Generalgouverneur in Belgien), was the administration dictrict’s president (Regierungspräsident) of Aachen, Maximilian von Sandt (1861-1918).

Governance Structure↑

The governor-general was the dominant figure of GG Belgium, namely because his temporary position had the highest sovereignty but also because he was subordinated[1] only and immediately to the German emperor. This meant he was removed from the influence and control of both the German government and German Reichstag in Berlin. The Zivilverwaltung was subordinated to him as well as[2] to the ministry of the interior (Reichsamt des Innern) in Berlin and the chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg (1856-1921). This joint subordination of the Zivilverwaltung would be the cause of numerous disputes between Brussels and Berlin as well as between the single occupation offices in the Belgian capital itself over the next few years – it was the neuralgic crux of the German occupation in Belgium.

Nevertheless, the scope of duties of the Zivilverwaltung and the “Government General” were defined in detail (in fundamental directives issued by the chancellor and the Prussian war ministry on 26 and 29 August 1914). The same applies to the activities of the military governors (Militärgouverneure) and the presidents of the civil administrations (Präsidenten der Zivilverwaltungen) in the provinces respectively of the military district chiefs (Kreischefs) and the civil commissioners (Zivilkommissare) in the Belgian arrondissements; these were issued on 23 October 1914 and, in the case of the Zivilkommissare, in December 1914. The revelation of the fact that the Präsidenten der Zivilverwaltungen and the Zivilkommissare were subordinate to both the prevailing military governors and Kreischefs as well as to the Zivilverwaltung in Brussels meant the development of an institutionally separate sphere at the level of the provinces and arrondissements, free from control of the central German civil administrations in Brussels and Berlin.[3]

Rather it was the governor-general’s right to exercise the directives for civil administration, a right granted to him in the autumn of 1914 – known as the “imperial legitimated governor-general’s reservation.”[4] This became the instrument used above all by Goltz’s successor Bissing to determine the systems of power and rule in the GG Belgium. It offered Bissing, who had in mind Germany’s long-term rule over Belgium, the opportunity to create several new occupation bodies (the “Political Division” or Politische Abteilung, the “Bank Division” or Bankabteilung and the “Division for Trade and Industry” or Abteilung für Handel und Gewerbe) in the spring and autumn of 1915. He did so at the expense of the Zivilverwaltung which was now subordinated directly to his person so that more and more important fields of occupation policy were removed from the control of the ministries of the German Reich in Berlin. There was no fundamental change under Bissing’s successor Falkenhausen, overlooking the fact that during the “administration separation” (Verwaltungstrennung) the central German Zivilverwaltung was separated into the new civil occupation bodies in June 1917: the “Administration chief Flanders” (Verwaltungschef Flandern) and “Administration chief Wallonia” (Verwaltungschef Wallonien) located in Brussels and Namur respectively. Unlike Bissing, Falkenhausen did not have the annexion of Belgium in mind and was skeptical about the French-dominated Belgian population’s potential for integration. His aim was instead, in full harmony with the German High Command, the radical continuation of the “administration separation,” looking forwards to Belgium’s final division into the two autonomous states Flanders and Wallonia (which would exist hierarchically beneath the German Reich).

Conclusion↑

Instead of the institutionalized and periodical cooperation between the single bodies and divisions of the Zivilverwaltung and the “Government General,” the governor-general ruled until the end of the occupation years with the help of the aforementioned occupation bodies and inter-official committees, commissions and personal commissioners (Persönlichen Beauftragten). Within this increasingly personalized (and of course fragile)[5] occupation order, numerous “cliques” of occupation officers competed in a “court like”[6] or “polycratic”[7] power structure to gain the governor-general’s favour. This strange “intermediate Reich” came to an abrupt end with the defeat of Germany and the breakdown of the German Kaiserreich in the autumn of 1918.

Christoph Roolf, Heinrich-Heine-Universität

Section Editor: Emmanuel Debruyne

Notes

- ↑ According to the “Characteristics [Grundzüge] about the military and economic exploitation of the kingdom of Belgium” ordered by Chief of the German General Staff Helmuth von Moltke (1848-1916) and signed by Wilhelm II on 25 April 1914.

- ↑ After direction by the German chancellor Bethmann Hollweg from 24 August 1914 and a circular letter by Clemens von Delbrück (1856-1921), state secretary at the Ministry of the Interior, on 26 August 1914.

- ↑ See Roolf, Christoph: Deutsche Besatzungspolitik in Belgien (in preparation).

- ↑ See Roolf, Christoph: Eine “günstige Gelegenheit”? In: Berg, Matthias / Thiel, Jens / Walther, Peter Th. (eds.): Mit Feder und Schwert. Militär und Wissenschaft-Wissenschaftler und Krieg, Stuttgart 2009, pp. 139f, and Roolf, Christoph: Deutsche Besatzungspolitik in Belgien (in preparation).

- ↑ Thiel, Jens: Menschenbassin Belgien, Essen 2007, pp. 39f.

- ↑ De Schaepdrijver, Sophie: Het koninkrijk België tijdens de Eerste Wereldoorlog [The Great War. The Kingdom of Belgium during the First World War], Amsterdam / Antwerp 1997, p. 130.

- ↑ Majerus, Benoît: Occupations et logiques policières, Brussels 2007, p. 350.

Selected Bibliography

- De Schaepdrijver, Sophie: La Belgique et la Première Guerre mondiale, Brussels 2004: Peter Lang.

- Majerus, Benoît: Occupations et logiques policières. La police bruxelloise en 1914-1918 et 1940-1945, Brussels 2007: Académie royale de Belgique, Classe des Lettres.

- Roolf, Christoph: Deutsche Besatzungspolitik in Belgien im Ersten Weltkrieg (1914-1918) (thesis in preparation), (forthcoming).

- Roolf, Christoph: Eine 'günstige Gelegenheit'? Deutsche Wissenschaftler im besetzten Belgien während des Ersten Weltkrieges (1914-1918), in: Berg, Matthias / Thiel, Jens / Walther, Peter Th. (eds.): Mit Feder und Schwert. Militär und Wissenschaft – Wissenschaftler und Krieg, Stuttgart 2009: Steiner, pp. 137-154.

- Thiel, Jens: 'Menschenbassin Belgien'. Anwerbung, Deportation und Zwangsarbeit im Ersten Weltkrieg, Essen 2007: Klartext Verlag.

- Wende, Frank: Die belgische Frage in der deutschen Politik des Ersten Weltkrieges, Hamburg 1969: Eckart Bohme.

- Zuckerman, Larry: The rape of Belgium. The untold story of World War I, New York 2004: New York University Press.