Introduction↑

How militarist was Europe in 1914? The question naturally hinges on what one means by the term “militarism”, and this is not easy to define in a straightforward way. As the historian Michael Howard (1922-2019) once noted: “Militarism, like ‘Fascism’ has become a term of such general illiterate abuse that the scholar must use it with care.”[1] Even Volker Berghahn ends his detailed study on the subject by admitting, in the book’s final paragraph, that “[w]e do not possess, it is true, an agreed theory of militarism.”[2] The following article explores the historiography of the term, and looks at militarism as a popular as well as an elite phenomenon. The text focuses for the most part on Europe, and in particular on the relationship between Great Britain and Germany, as these countries have featured prominently in discussions of the nature and character of militarism.

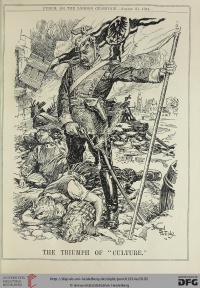

For a variety of reasons, Europeans often looked to Germany when discussing militarism, and German society itself was at times seen as a prime example of militarism in practice. In Germany and the Next War, a book that was widely read in Britain after its translation into English in 1912, General Friedrich von Bernhardi (1849-1930) spent much time extoling the use of force in international politics. For Germans, he wrote, “[a] rude shock is needed to awaken their warlike instincts, and compel them to show their military strength”.[3] “[W]e must admit”, a commentator in the British Saturday Review noted after having read a copy, “that those who distrust the Teuton have here some very tangible justification for their attitude”.[4] As a description of German perfidy, and of Germany’s apparent quest to conquer their neighbours with brute force, the book was understood by some in Britain as a roadmap to war – a conclusion that became all the more convincing when conflict broke out in the summer of 1914. A reviewer in The Academy in September 1914, at which point Bernhardi’s work had been reissued in English in a cheaper format, saw the work as illustrative of German militarism, and argued that Britain’s aim in the First World War should be “the breaking of the military incubus”. In pursuing military prowess, it seemed Germany had placed itself outside of civilisation.[5]

Such claims were perhaps easy to make during the opening stages of the First World War, when German troops had struck through neutral Belgium and, as was widely reported in the British press, had committed atrocities against Belgian civilians. Yet, if proof of German militaristic tendencies was what commentators were looking for, Bernhardi's polemic - for all its aggression - was a curious smoking gun to point to. True, it described a Germany that was, in Bernhardi’s opinion, “torn by internal dissensions, yet full of sustained strength”,[6] and a country that could be united in the common cause a war would bring. But the general also opened the book with an examination of “the aspirations for peace, which seem to dominate our age and threaten to poison the soul of the German people, according to their true moral significance”.[7] Despite its bellicose title, Germany and the Next War did not describe a German public which clamoured for military expansion, but, on the contrary, one that was rather too docile and peaceful for Bernhardi’s own liking.

Friedrich von Bernhardi’s reception in Britain, and how his book was read after August 1914, illustrates the difficulty in trying to understand militarist attitudes in Europe before the outbreak of war. While Bernhardi himself was certainly no dove, there is an inherent danger in trying to read a more widespread sentiment into his publication. If anything, the book shows how militarism can be a complex and uneasy concept, often difficult to spot or nail down even for those who are looking for it.

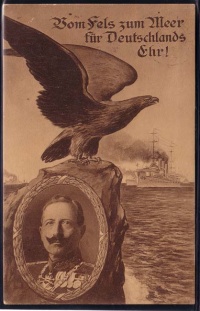

If looked at exclusively top-down, militarism can imply the subordination of civilian authority to the decisions of the armed forces. According to this definition, however, the degree of “militarism” in different states is rather unclear. All European countries in 1914 to some degree or another saw an overlap in the civilian and military decision-making process regarding peace and war, and sovereigns from Britain to Russia often wore military uniforms – though not all delighted in it to the same degree as Germany’s emperor Wilhelm II, (1859-1941). Crowned heads of state also liked to wear the uniforms of other nations – Wilhelm, again, is a prime example – meaning that the wearing of uniforms, at least on its own, was hardly a symptom of rampant xenophobia or the wish to conquer neighbouring countries. It is also worth remembering that it takes more than a uniform to start a war; and though they can be symbolic, what uniforms symbolise may differ depending on the situation.

Indeed, if military authority over the civilian government is the benchmark for militarism, pre-1914 Serbia, to take one example, emerges as much more “militarist” than Germany. The Serbian king had been installed after a military coup in 1903, where his predecessor had been brutally murdered, whereas Wilhelm and his ministers were often (though not always) frustrated in their attempts at expanding the armed forces by the opposition of an intransigent Reichstag, with its large contingent of Social Democrat representatives, eager to assert its own powers. In Sweden, a country rarely thought of as “militaristic”, Gustav V, King of Sweden (1858-1950) precipitated a government crisis in early 1914, when he forced out the sitting Liberal Prime Minister over a disagreement regarding military spending.

If, on the other hand, militarism is analysed from the bottom-up, another equally complex image emerges. To what extent were governments’ policies shaped by popular pressure? Or were the popular pressures rather informed and shaped, or indeed manipulated, by the states’ elites, whether cultural, political or otherwise? Howard noted that militarism can be defined as a society’s acceptance of the values of the military subculture. And according to this definition, he argued:

The risk here, of course, is that the term becomes somewhat difficult to define, and, as a result, becomes less useful to historical analysis.

With the above issues in mind, to understand the nature of militarism in European society, and the way it could be used to explain the events leading up to the July Crisis, one first needs to understand how the term has been analysed and understood historically. After a brief look at the history of the term, the analysis turns to popular militarism in Europe, and asks to what extent this can be used to explain the outbreak of the First World War, and the popular support for the war effort.

The historiography of pre-1914 militarism↑

Alfred Vagts (1892-1986), writing in the inter-war years, noted how the word “militarism” could be traced back to Second Empire France, in the 1860s, where the term “was employed, like the coeval concept, ‘imperialism,’ by the Empire’s republican and socialist enemies”.[9] It was across the English Channel, however, that the concept was first seriously and systematically analysed.[10] Writing in the 1880s, the liberal sociologist, biologist and polymath Herbert Spencer (1820-1903) set out to describe the differences between what he termed militarist – or “militant” – societies, and industrial societies, in his work The Principles of Sociology. The terminology can be a bit misleading: the former, he argued, was a society that subjected the individual’s needs to that of the state; while the latter was defined by liberal individualism. As such, he argued, socialism displayed just as many militarist tendencies as did Prussianism; the definition based itself on a distinction between the regimentation imposed from above in a “militant” society, versus the personal freedom present in an “industrial” society.[11]

As Berghahn notes, Spencer’s liberalism and 19th century faith in “Progress”, lead him to envision that the world would gradually move away from militant social organisation, towards a liberal, industrial one.[12] Yet, for all his Whiggish optimism, Spencer also feared that the late-Victorian era could go in a different direction: he identified a possible “recrudescence” of militancy – as evidenced through increased expenditure on armaments, but also in imperial expansion and in the regimentation of British civilians through public schools, the volunteer movement and militant boys’ organisations.[13] In Britain, as well as in France, criticism of militarism or “militancy” was therefore from an early stage linked to anti-imperialism. British Liberal and Radical critics of war continued to lump these two – militarism and imperialism – together, both before and after the World War. Thus, J.A. Hobson’s (1858-1940) criticism of the 1899-1902 South African War focused on the popular nature of “jingoism” – broadly defined as the celebration of military victories, and an expressed eagerness to take up arms against foreign enemies – which he believed led Britain into imperial wars.[14] In the 1970s and 1980s, British historians returned to this aspect of Spencer’s ideas – or, more accurately, arrived at similar conclusions on their own – with a series of studies that identified religious and youth organisations as sources of pre-1914 British militarism as well as imperialism.[15]

The British approaches to analyses of militarism – from Spencer onwards – were often predicated on what is termed the Primat der Innenpolitik, or primacy of domestic politics: pressures from within British society, Spencer argued, led to imperial expansion and international tension. Hobson’s argument followed along similar lines. A competing theory saw military organisation – and the level of militarism – as the result of external pressures; this is predicated on the primacy of foreign politics, or Primat der Aussenpolitik. A proponent of this perspective was the German historian Otto Hintze (1861-1940), in a lecture delivered in 1906. According to Hintze, states were politically (and, by implication, militarily) ordered depending on their position in the international system. Dismissing the idea that an internal development, like class struggle, determined the state’s organisation, Hintze instead proposed that, “throughout the ages, pressure from without has been a determining influence on internal structure”.[16] War and conflict shaped and indeed defined the state according this analysis, variations of which can be traced in the later work of Max Weber (1864-1920) – who saw the state’s ability to utilise or control violence within its borders as its defining feature – and in Charles Tilly’s (1929-2008) pithy statement that “war made the state, and the state made war.”[17]

In Hintze’s view, the different nature and level of external threats had led to different ideas of military organisation in early modern Europe. Safe from invasion, British self-government was free to develop unimpeded by foreign threats, whereas the continental powers – Prussia, in particular – took a different route. “Absolutism and militarism”, Hintze stated, “go together on the Continent just as do self-government and militia in England”.[18] This idea – that external threats shape political and social systems – has been central to many other interpretations of European state organization. There is much Hintze would have agreed with in his contemporary Halford Mackinder’s (1861-1947) theories on geopolitics, in particular how individual nations are shaped by external forces.[19]

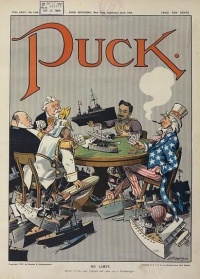

Hintze’s argument also raises the central question of whether it makes sense to talk of a distinction between militarism and “navalism”; or, to put the question differently, whether militarism belongs solely to societies with a strong military tradition, rather than to those with a naval tradition. Although he does not reference Hintze, Andrew Lambert’s recent argument that “seapower states” like 19th Britain were defined as much by their cultural and political dimensions as their military ones, has a lot in common with the theories of the German thinker. As Lambert writes, “seapower” states were “politically inclusive, outward looking and dynamic”, and only able to put large armies in the field at great, and ultimately destructive cost.[20] Seapowers, Lambert contends, are defined partly by their inclusive political systems and their commercial orientation – a definition that seems to adhere to Spencer’s idea of an “industrial”, as opposed to a “militant” state. Leaving navies, and a naval society like pre-1914 Britain, outside of a discussion of pre-war militarism creates its own problems, however, of which more later.

In the wake of the First World War, and in particular after the Second World War, historians and political scientists have applied various other analyses to the question of what militarism is. However, these are, for the most part, variations on the abovementioned concepts of either a “top-down/bottom-up”, or an “internal/external” (Primat der Innenpolitik vs. Primat der Aussenpolitik) heuristic approach. According to Alfred Vagts, “militarism” denoted the irrational pursuit of military glory; the ways wars were planned and fought defined the nature of militarism, not necessarily the wars themselves. “Militarism”, wrote Vagts,

This broad and somewhat uneasy definition makes Vagts’ analysis less useful for the purposes of the discussion here, though it should be mentioned as one example of how “militarism” does not necessarily entail anti-militant sentiment. Indeed, James Joll (1918-1994) and Gordon Martel point to the prevalence of what can be termed “militant anti-militarism”, in particularly among French revolutionary syndicalists, in the years prior to 1914.[22] Revolutionary groups across Europe often had a militant streak to them, though anti-militarism also formed an important component part of their worldview. The broken rifle, for example, was used as a peace symbol by the left in Germany and Scandinavia in the lead-up up to the outbreak of the war.

In the political sciences, the relationship between the armed forces and the civilian government has been the focus in numerous studies, from Harold D. Lasswell’s (1902-1978) description of the “garrison state” concept – a state where the soldier, “the specialist on violence”, was in charge of economy and society – to the analyses of the influence of the ‘military mind’ on the state, and of civil-military relations by Samuel P. Huntington (1927-2008) and Amos Perlmutter (1931-2001), to name but a few of the more influential theorists.[23] These studies naturally focus on the structural relationship between institutions within states or within state systems.

Popular Militarism: The Patriotic Societies↑

Leaving the structural question regarding influence of military thinking on state policy to one side, let us instead focus on the popular nature of militarism – the “jingoism” described and criticised by writers like Hobson.

There was certainly no shortage of military or military-inspired paraphernalia in pre-First World War Europe. Paul Fussell (1924-2012), who himself wore a U.S. infantry uniform in the Second World War (and a Boy Scout uniform before that), notes that, “[b]y the time General Robert Baden-Powell founded the Boy Scouts, in 1908, the idea of uniformed youth may have become rather tired”.[24] In Britain alone there were enough youth groups – from the Boys Brigade to the Church Lads Brigade and the Jewish Lads Brigade – to appeal to a large and varied segment of pre-war youth. There were groups for girls as well as boys, and many more organisations catering to a more mature audience. If one were so inclined, a British adult could enjoy membership in a variety of societies linked in one way or another to the armed forces. The National Service League, from 1905 led by the former Commander-in-Chief of the British army, Lord Frederick Roberts (1832-1914), could boast an impressive list of followers on the eve of the war. Among its 200,000 supporters in 1912, of which 100,000 were active members, the League could list over 100 MPs, according to Anne Summers.[25] Other Britons looked to the sea, and supported the Navy League, established in the mid-1890s. However, the Navy League was beset by infighting and did not have a charismatic leader as Roberts to hold it together. A breakaway group finally left to form the competing Imperial Maritime League in 1908.[26]

Popular groups like the National Service League and the Navy League received much attention by scholars in the 1980s, not least as part of studies on the rise of what has been termed the radical right, and often as part of comparative studies between Britain and Germany.[27] Yet the leagues’ influence seems to have been rather limited, both culturally and politically. Serving Army officers tended to avoid the National Service League, and Anne Summers notes that it mainly attracted a Conservative and Anglican membership. Few working-class members seem to have been interested in joining the organisation.[28] The Navy League as well had strong upper-class and Conservative leanings, according to Frans Coetzee,[29] meaning that such organisations often catered to a limited political audience. Anne Summers notes that it “seems highly unlikely that any Radicals or Socialists ever actually joined the National Service League”.[30] That said, there were certainly at least some British left-leaning proponents of national service in some form or other, albeit not always for the same reasons as the League’s middle-class membership. Socialists like Robert Blatchford (1851-1943), editor of the newspaper Clarion, wrote passionately about the need to oppose the perceived threat from Germany, including in articles for the Daily Mail in late 1909, and directly in written correspondence with Lord Roberts.

Blatchford’s distrust of German intentions illustrates how British pro-military sentiment before the war could be predicated on the fear of foreign aggression. “Jingoism”, Summers writes, “was a defensive reaction to a perceived external threat. Popular nationalism was not an aggressive or outward-looking force”.[31] This was certainly true when it came to some of the members of the various Leagues, but it is difficult to prove that jingoism and fear were particularly deeply held in Britain beyond during specific and time-limited outbursts. British society as a whole was hardly paralysed with fear over external aggressors in the pre-First World War decades. One should be careful to extrapolate from the existence of some popular groups, containing a rather limited socio-economic cross-section of society, that all Britons accepted the Leagues’ arguments. Indeed, the organisations’ arguments were often in conflict with each other, as well.

With its small army and powerful navy, Britain was in many ways an outlier in the summer of 1914. Its reliance on a volunteer army, and its theoretical ability to remain largely aloof from continental commitments due to its insular position and the “wooden walls” of the Royal Navy, meant that discussions of intervention in July and August took on a different character than in other countries. For France and Germany, for example, the mobilisation for war in 1914 from an early stage took on the guise of self-defence, whereas the British government instead presented its decision to intervene in defence of small states like Belgium, and as standing up to German aggression – whether this was true or not is neither here nor there. The elevated status of the fleet in British society, as opposed to the army, seems to point towards a country more in line with Hintze’s and Spencer’s idea of a less militaristic or “militant” society than the states on the European continent. There are, however, many comparisons that can be made between pre-war popular support for the armed forces and for military action in Britain and in Germany, making this distinction less clear.

In Germany, as in Britain, popular leagues in support of a large navy sprang up in the decades prior to 1914, and these too attracted large memberships. Naturally, there were differences between the two countries, and between the British Navy League and its counterpart, the German Flottenverein (Navy League), in particular. The Royal Navy’s position in society was firmly established long before the naval arms race, whereas the German navy had nowhere near the same position in German society. The need for an active pressure group in Britain seemed decidedly less important than it did for the promoters of a German battlefleet. But there are many points of comparison, as well. As Frans Coetzee and Marilyn Shevin Coetzee have noted, members were attracted to the patriotic societies in both Britain and Germany for a variety of different reasons, not least of which was the theatrical element: “Politics was a form of theatre and the patriotic societies, in serving a political function, were simultaneously serving a social one in providing a form of entertainment”.[32] In Jan Rüger’s study of the Anglo-German naval race, the theatrical element plays a key role: both Britain and Germany were engaged in much more than a weapons race, the navies were also presented as popular cultural expressions of the two nations. The launch of a new warship was also a grand public event, and the naval race was therefore intimately tied to the rise of modern mass media.[33]

Newspapers and Nationalism↑

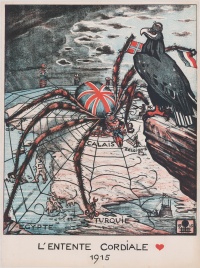

Nationalism was shaped by the printed word. In Benedict Anderson’s (1936-2015) phrase, the “imagined community” of a modern nation state was tied together by the printing press.[34] Nationalism and the printed word have also been blamed for the outbreak of the war, or at least for fuelling xenophobia and, ultimately, militarism across Europe. “Among the tectonic plates shaping the context of international politics”, notes Samuel R. Williamson, “none loomed as dangerous and irrational as rampant, virulent, passion-filled nationalism ... [B]y 1914 nationalism had become the plaything of politicians and the intelligentsia”.[35]

However, the role of nationalism in pre-war politics, and the influence of the press in shaping and promoting it, remains unclear. Newspapers, in particular the large-circulation papers and periodicals, like the aforementioned Daily Mail in Britain, have often received a bad press from historians.[36] But it is worth remembering that, while some European newspapers clearly pushed specific policies – not least when it came to imperial adventurism or xenophobic diatribes in times of international tension – newspapers were often just as eclectic as their wide and varied readership. The written word in an age of mass media never pulled consistently in one direction, and any interested reader could pick up and read a range of different opinions in newspapers across the continent, apart from the limitations put in place by state censorship, of course. Countries with large left-wing parties also had large-circulation newspapers with left-leaning – and often quite explicitly anti-militaristic – opinions, and readers probably had a tendency to seek out and read the papers they agreed with, rather than radically change their own political standpoints if and when a newspaper told them to.

Even when newspapers and other publications seemed to argue for specific ideas, they were often read in different ways by a readership that was able to read and interpret such ideas according to their own convictions. For example, there has long been a tendency in scholarship to portray Britain, in particular, as fearful of foreign invaders in the period leading up to the outbreak of the First World War. While some, like Robert Blatchford, dedicated their time and their pens to try to warn the public of the dangers of war and invasion, little research has been done on how the British public reacted to their warnings. To take one example, while there are indications that many did indeed read and engage with the widely popular and ubiquitous future-war and invasion-scare literature of the period, the responses to this was varied rather than uniformly “fearful.”[37] A similar analysis can be applied to those stories that portrayed military conflict in a positive light, and while it has been claimed that a country like pre-First World War Britain was steeped in a culture of militarism – a “pleasure culture of war” as it has been termed[38] – there are few indications that Britons became more bloodthirsty as a direct result of reading about military exploits.

Fictional depictions of future wars and invasions could, however, enforce images of foreign threats, and thereby strengthen the feeling within a country that it was indeed threatened by outside forces. One example here is Sweden, where Russia figured as a bogeyman for many future-war fiction authors in the decades before the war broke out.[39] Future-war fiction could very well have reflected real fears in societies, or at least among groups within these societies, at certain points in time. That said, it is doubtful if the stories on their own drove xenophobia or created the conditions necessary for war; after all, Sweden and Russia did not come to blows in 1914.

Fear and jingoism may in any case – at least at first glance – have coexisted: an opinion often expressed in the inter-war years argued that Britain had in fact entered the conflict on a wave of public enthusiasm that carried the political decisions before it. David Lloyd George (1863-1945) claimed in his memoirs that the British government had the public solidly behind them when they intervened against Germany in the summer of 1914. Indeed, Lloyd George presented the decision as more the result of public pressure than the rational calculations of British statesmen. “All wars are popular on the day of their declaration”, he wrote. “But never was there a war so universally acclaimed as that into which Britain entered on the 4th of August of 1914”.[40]

Of course, Lloyd George had a vested interest in portraying the government that he was a part of as acting according to the will of the people. However, such claims have been challenged by historians, and it now seems clear that the British public’s reaction to the news of hostilities breaking out in Europe was decidedly more mixed than Lloyd George argued.[41] As Catriona Pennell has shown, there were crowds in Britain and Ireland who opposed the war, as well as those who supported it, in addition to much insecurity and general disbelief as peace broke down in Europe. Support for the war was not panicked or cold-blooded among British and Irish people: “Rather”, Pennell writes, “their support was very often carefully considered, well-informed, reasoned, and only made once all other options were exhausted”.[42]

Similarly, the myth of the “spirit of 1914” in Germany – where the nation supposedly rallied enthusiastically in support of the war – has been challenged by historians, not least in an in-depth study by Jeffrey Verhey. Verhey used newspapers to map the German reactions to the July crisis and the declaration of war, and found that, while there were certainly some crowds in support of armed conflict, many Germans were much more apprehensive.[43] A pioneering earlier study by Jean-Jacques Becker has shown a similar variety in the French reactions to the outbreak of war,[44] and both Becker and Verhey see differences between the rural and urban reactions in both countries.[45] As Roger Chickering has observed, the scenes in German streets in 1914 “should not be taken as evidence that an inveterate German war enthusiasm made war probable or inevitable”.[46] These conclusions hardly point to deeply held militaristic attitudes in either country in the lead-up to war, and public opinion can certainly not be blamed for pushing the statesmen in one direction or other when the decisions for war were made.

Imperialism↑

Imperial policies could often find both strong and vocal support within the pages of European newspapers. As the term “imperialism” is so closely connected to militarism – at times the two are virtually indistinguishable both in contemporary and historical debates – it needs to be included in this discussion.

Increased imperial expansion in Africa from the 1870s onwards, during the period known as the “New Imperialism”, led the European powers into potential conflict with each other. Commentators like J.A. Hobson saw this imperial expansion as a potential driver for popular militarism, and while it would be going too far to attribute late-19th century imperial conquests to popular pressure within European society, there were certainly many who saw imperial possessions as a necessity for any self-respecting Great Power.

The scramble for Africa increased tensions across Europe, and fuelled jingoistic sentiments in newspapers and in patriotic societies. In Italy, where a race for colonies combined with particularly virulent fin-de-siècle nationalist sentiments – directed, in particular, towards the regions of “Unredeemed Italy” (Italia Irredenta) outside of the country’s borders – the pre-war years saw a decline of traditional liberal politics and the rise of more extreme political ideas. Italy had the luxury to wait and see which way the wind was blowing during the July crisis, and remained neutral in 1914. In May 1915, however, nationalist crowds filled the streets, forcing Giovanni Giolitti (1842-1928), the leading light among neutralist liberal politicians, to admit defeat. Italy joined the war, seemingly on a wave of populist militarist excitement. Imperial adventurism and a vibrant nationalism had forced parliament’s hand. However, as Christopher Duggan (1957-2015) observes, the crowd’s anger was directed towards the political system itself, rather than against any outward enemy: “The crowds calling for intervention”, he writes, “were fired as much by anger towards Giolitti and the neutralists as by enthusiasm for war”.[47] As Paul Corner notes, Italy’s decision to join the war came at a time when the Italian state was facing a crisis of legitimacy, and had already experienced widespread discontent. Giolitti’s failure, as prime minister until 1914, to stabilise the Italian political system had alienated both left and right, and there were dark clouds on the political horizon. For Antonio Salandra (1853-1931), Giolitti’s successor, joining the war seemed to offer a way out of Italy’s political predicaments.[48]

The Italian decision to join the European conflagration is a pointed example of how pre-war popular militarism can be a difficult animal to clearly identify, and how it could be shaped and fuelled by concerns and issues that were specific to certain countries and to their previous experiences. In Italy’s case, the move to war was clearly influenced by the political system that had developed during the country’s quest for imperial greatness, and that were now creaking at its seams.

The Italian example also shows how parliaments, governments and rulers could find themselves reacting to popular politics, rather than try to shape and guide it. Most of the other major European countries, however, found themselves in a different situation, as the events of July 1914 drove the decisions for war within the foreign ministries and at the high commands. It seems clear that any widespread, popular groundswell pushing for war largely existed in the minds of statesmen like David Lloyd George. The blame for war in 1914 cannot therefore convincingly be laid at the feet of the European people, but should be reserved for their leaders.

Militarism at the top: governments and the armed forces↑

One European Great Power stands out in particular when it comes to the question of militarism: Russia. The society of pre-First World War Russia was shaped in large part by its imperial project. But unlike Italy, for example, Russia was an imperial power because of its control over a large continental landmass, as opposed to overseas colonies. Yet Russian officials sought to emulate other colonial powers, like France, in its governing of this landmass. “Russia’s domestic civil rule”, as Peter Holquist has observed, “was therefore more ‘colonialized’ and ‘militarized’ than most other European powers”.[49] Pre-war society in Tsarist Russia was to a large degree shaped by the role of violence in its politics; it was a society in large part based on the logic of a militarised state apparatus. This continued after October 1917: when Max Weber linked the modern state to its monopoly on the legitimate use of violence, he opened by quoting Leon Trotsky (1879-1940) at Brest-Litovsk: “Every state”, Trotsky argued, “is founded on violence”.[50] This was certainly the case in Russia.

Although the Russian case is an extreme one, other states were of course also largely shaped by a similar logic. As noted above, crowned heads of state were either titular or in various degrees de facto heads of both civilian government and the armed forces in their respective countries. Indeed, the modern European state, with its efficient bureaucracy, taxation, and ability to register and mobilise its inhabitants, was to a very large degree either directly shaped by and for war, or eminently capable of being reorganised for the purposes of fighting one. There were also clear links between officials in government positions and the patriotic societies in countries like Britain and Germany, as mentioned earlier. Serving and retired officers served as members of the British Parliament, and the Junker class in Germany saw itself as natural leaders both in peace and in war. Private industry also had links with the armed forces and with politicians alike: when it came to Germany, the real or imagined influence of the Krupp family has gained almost mythical status, yet in liberal Britain and France, too, private industry and decision-makers in politics and in the armed forces were in close contact with each other before the war. Indeed, David Edgerton has argued the British state of this period as one shaped by what he termed a “liberal militarism.”[51]

Whether such connections made a European war more likely or not is a different question. Politicians deferred to military planners – whether intentionally or not – in the lead-up to war, letting the logic of military planning and mobilisation take on a life of its own. The push for war, or for decisive measures, may have been influenced by the way politics were, to a degree, organised around the conduct of war. However, across Europe in the summer of 1914 the foreign offices worked towards their own solutions to the crisis. Mobilisation, sabre-rattling and declarations of war were only some of the tools in states’ toolkits in 1914. To call this “militarism” in, say, Harold Lasswell’s sense – a “garrison state” where the military made decisions in peace as well as in war – may be going too far.

Of non-European belligerents, Japan seems to fit the description of top-down militarism best. In the aftermath of the Second World War, post-Meiji Restoration Japan was often pointed to as an example of a society where civilian authority had been subsumed by the power of the armed forces. As Berghahn writes, “[t]he influence of the military in Japanese politics and society after 1868 was so blatantly obvious that most [post-Second World War] historians never agonized as much as the Germans over the applicability of the concept of militarism”.[52] Though here as well the image is slightly less clear than a first glance would suggest. In the final decades of the 19th century, certain civilian leaders often had extensive oversight over the armed forces, though this was partly due to some of them having been samurai prior to the Restauration.[53] In either case, the idea of a thoroughly militarised society, where the armed forces decided policy, belongs more to the inter-war period, rather than the years leading up to 1914.

Conclusions↑

Without a clear and incontestable definition of militarism, it becomes difficult to make clear and incontestable conclusions as to its prevalence in pre-First World War society. Many civilians across Europe willingly joined patriotic societies, or supported movements for increased armaments, or dressed their sons and daughters in uniforms. Enthusiasm for war – or for the symbols of war – took on different guises in different countries, but there were many similarities as well. Britain and Germany both saw their respective navies as a national unifying symbol, despite the more important role the German army held in German society compared to its British counterpart. Public displays of enthusiasm for the armed forces or for nationalist symbols or sentiments did not, however, necessarily make the public in general more likely to support a Great War in 1914. For many the spectacle of military parades and fleet reviews were just that: spectacle and entertainment. We are therefore left with a somewhat mixed picture of pre-war militarism. On the one hand, military language, uniforms and symbols had to a large degree conquered civilian society – as evidenced by the youth organisations, patriotic societies and military and fleet displays so popular across Europe. Yet these symbols meant different things to different people, and popular militarism may not have translated into popular aggression.

As for the governments themselves, the various degrees of influence the armed forces held over civilian society makes it difficult to see how much leeway the generals and admirals really had in the lead-up to war. Nicholas II, Emperor of Russia (1868-1918), and Wilhelm II in Germany, had much theoretical power over both civilian government and the armed forces, but the exercise of this power was limited by many checks and balances – official or otherwise. These were not ancient despots, able to demand unquestioning loyalty from their state apparatus or their populations. If the pre-war states and societies could be said to be militaristic, it was therefore a militarism of degrees rather than an absolute and all-encompassing phenomenon.

Christian K. Melby, Western Norway University of Applied Sciences

Section Editors: Annika Mombauer; William Mulligan

Notes

- ↑ Howard, Michael: War in European History, Oxford 2009, p. 109.

- ↑ Berghahn, Volker R.: Militarism. The History of an International Debate, 1861-1979, Cambridge 1981, p. 123.

- ↑ Bernhardi, Friedrich von: Germany and the Next War, transl. Allen H. Powles, London 1912, p. 2.

- ↑ Saturday Review, 7 December 1912, pp. 711-712.

- ↑ The Academy, 12 September 1914, pp. 300-301.

- ↑ Bernhardi, Germany and the Next War 1912, p. 67.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 6.

- ↑ Howard, War in European History 2009, pp. 109-110.

- ↑ Vagts, Alfred: A History of Militarism. Civilian and Military, London 1959, p. 14.

- ↑ Berghahn, Militarism 1981, p. 11.

- ↑ Spencer, Herbert: The Principles of Sociology 3 vols. London, 1876-1896, II, 658-730; III, 585-586.

- ↑ Berghahn, Militarism 1981, p. 13, p. 107.

- ↑ Spencer, Principles, 1876-1898, vol. III, p. 590.

- ↑ Hobson, J.A.: The Psychology of Jingoism, London 1901.

- ↑ See Anderson, Olive: The Growth of Christian Militarism in Mid-Victorian Britain, in: English Historical Review, 86 (1971), pp. 46-72; Summers, Anne: Militarism in Britain before the Great War, in: History Workshop, 2 (1976), pp. 104-123; Springhall, J.O.: The Boy Scouts, Class and Militarism in Relation to British Youth Movements 1908-1930, in: International Review of Social History, 16 (1971), pp. 125-158; Springhall, J.O: Baden-Powell and the Scout Movement before 1920. Citizen Training or Soldiers of the Future?, in: English Historical Review, 102 (1987), pp. 934-942.

- ↑ Hintze, Otto: Military Organization and the Organization of the State, in: Gilbert, Felix (ed.): The Historical Essays of Otto Hintze, New York 1975, p. 183. Here Hintze was, of course, in fundamental disagreement with Marxist thinkers like Vladimir Lenin (1870-1924), who saw the state as a result of precisely class antagonisms: e.g., Lenin, V.I.: The State and Revolution, in: The Classics of Marxism, vol. 1, London 2011), pp. 77-173. See pp. 80-82 in particular.

- ↑ See Weber, Max: Politics as Vocation, New York 1946; Tilly, Charles: Reflections on the History of European State-Making, in: Tilly, Charles (ed.): The Formation of National States in Western Europe, Princeton 1975, pp. 3-83, at p. 42.

- ↑ Hintze, Military Organization 1975, p. 199.

- ↑ See Mackinder, H.J.: The Geographical Pivot of History, in: Geographical Journal, 23 (1904), pp. 421-437.

- ↑ Lambert, Andrew: Seapower states. New Haven et al. 2019, p. 11, p. 15.

- ↑ Vagts, Militarism 1959, p. 17.

- ↑ Joll, James /Martell, Gordon: The Origins of the First World War, Harlow 2007, p. 88.

- ↑ Lasswell, Harold D.: Sino-Japanese Crisis. The Garrison State versus the Civilian State, in: The China Quarterly, 2 (1937), pp. 643-649; Huntington, Samuel P.: The Soldier and the State. The Theory and Politics of Civil-Military Relations, Cambridge, MA. 1957; Perlmutter, Amos: The Military and Politics in Modern Times. On Professionals, Praetorians, and Revolutionary Soldiers, New Haven et al. 1977.

- ↑ Fussell, Paul: Uniforms. Why We Are What We Wear, Boston 2002, p. 162.

- ↑ Summers, Anne: The Character of Edwardian Nationalism. Three Popular Leagues, in: Kennedy, Paul / Nicholls, Anthony (eds.): Nationalist and Racialist Movements in Britain and Germany before 1914, London et al. 1981, pp. 68-87, at p. 70.

- ↑ Coetzee, Frans: For Party or Country. Nationalism and the Dilemmas of Popular Conservatism in Edwardian England, New York et al. 1990, pp. 83-84.

- ↑ See Kennedy and Nicholls (eds.), Nationalist and Racialist Movements 1981; and Coetzee, Frans/Coetzee, Marilyn Shevin: Rethinking the Radical Right in Germany and Britain before 1914, in: Journal of Contemporary History, 21 (1986), pp. 515-537.

- ↑ Adams, R.J.Q. / Poirier, Philip P.: The Conscription Controversy in Great Britain, 1900-18, Basingstoke 1987, p. 20.

- ↑ Coetzee, For Party or Country 1990, p. 29.

- ↑ Summers, Three Popular Leagues 1981, 76.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 73.

- ↑ Coetzee/Coetzee, Rethinking the Radical Right 1986, p. 518.

- ↑ Rüger, Jan: The Great Naval Game. Britain and Germany in the Age of Empire, Cambridge 2009.

- ↑ Anderson, Benedict: Imagined Communities. Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism, London 2006.

- ↑ Williamson, Jr., Samuel R.: The Origins of the War, in: Strachan, Hew (ed.): The Oxford Illustrated History of the First World War, Oxford 2000, p. 13.

- ↑ See, for example, A.J.A. Morris’ old but still relevant The Scaremongers. The Advocacy of War and Rearmament, 1896-1914, London 1984.

- ↑ On this, see Melby, Christian K.: Empire and Nation in British Future-War and Invasion-Scare Fiction, 1871-1914, in: Historical Journal, 63 (2020), pp. 389-410.

- ↑ E.g. Paris, Michael: Warrior Nation. Images of War in British Popular Culture, 1850-2000, London 2000.

- ↑ Ahlund, Claes: Den svenska invasionsberättelsen – en bortglömd litteratur [The Swedish invasion story – a forgotten literature], in: Tidsskrift för litteraturetenskap, 3 (2003), pp. 82-103.

- ↑ Lloyd George, David: War Memoirs, 2 vols., London 1938, I, p. 42.

- ↑ E.g. Newton, Douglas: The Darkest Days. The Truth Behind Britain’s Rush to War, 1914, London et al. 2014.

- ↑ Pennell, Catriona: A Kingdom United. Popular Responses to the Outbreak of the First World War in Britain and Ireland, Oxford 2012, p. 4.

- ↑ Verhey, Jeffrey: The Spirit of 1914. Militarism, Myth and Mobilization in Germany, Cambridge 2000.

- ↑ Becker, Jean-Jacques: 1914. Comment les Français sont entrés dans la guerre, Paris 1977. See also Becker, Jean-Jacques: Willingly to War. Public Response to the Outbreak of War, in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War, ed. by Ute Daniel, Peter Gatrell, Oliver Janz, Heather Jones, Jennifer Keene, Alan Kramer, and Bill Nasson, issued by Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin 2015-06-15. DOI: 10.15463/ie1418.10656. Translated by: Jones, Heather.

- ↑ Verhey, The Spirit of 1914 2000; Becker, Jean-Jacques: Willingly to War. Public Response to the Outbreak of War, in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War, ed. by Ute Daniel, Peter Gatrell, Oliver Janz, Heather Jones, Jennifer Keene, Alan Kramer, and Bill Nasson, issued by Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin 2015-06-15. DOI: 10.15463/ie1418.10656. Translated by: Jones, Heather.

- ↑ Chickering, Roger: War Enthusiasm? Public Opinion and the Outbreak of War in 1914, in: Afflerbach, Holger / Stevenson, David (eds.): An Improbable War. The Outbreak of World War I and European Political Culture before 1914, New York et al. 2007, pp. 200-212, at p. 200.

- ↑ Duggan, Christopher: The Force of Destiny. A History of Italy since 1796, London 2008, p. 388.

- ↑ Corner, Paul: The Road to Fascism. an Italian Sonderweg?, in: Contemporary European History, 11 (2002), pp. 273-295.

- ↑ Holquist, Peter: Violent Russia, Deadly Marxism? Russia in the Epoch of Violence, 1905-21, in: Kritika, 4 (2003), pp. 633-634.

- ↑ Weber, Politics as Vocation 1946, p. 3.

- ↑ See Edgerton, David: Liberal Militarism and the British State, in: New Left Review, 185 (1991), pp. 138-169; and idem, Warfare State. Britain 1920-1970, Cambridge 2006.

- ↑ Berghahn, Militarism 1981, p. 64.

- ↑ See Kitaoka, Shin'ichi: The Army as a Bureaucracy: Japanese Militarism Revisited. in: The Journal of Military History 57 (1993), pp. 67-86, at pp. 69-70.

Selected Bibliography

- Anderson, Olive: The growth of Christian militarism in mid-Victorian Britain, in: The English Historical Review 86/338, 1971, pp. 46-72.

- Becker, Jean-Jacques: 1914. Comment les Français sont entrés dans la guerre. Contribution à l'étude de l'opinion publique printemps-été 1914, Paris 1977: Presses de la Fondation nationale des sciences politiques.

- Berghahn, Volker R.: Militarism. The history of an international debate, 1861-1979, Cambridge 1984: Cambridge University Press.

- Chickering, Roger: War enthusiasm? Public opinion and the outbreak of war in 1914, in: Afflerbach, Holger / Stevenson, David (eds.): An improbable war. The outbreak of World War I and European political culture before 1914, New York 2007: Berghahn Books, pp. 200-212.

- Coetzee, Frans; Shevin-Coetzee, Marilyn: Rethinking the radical right in Germany and Britain before 1914, in: Journal of Contemporary History 21/4, 1986, pp. 515-537.

- Edgerton, David: Liberal militarism and the British state, in: New Left Review 185, 1991, pp. 138-169.

- Hintze, Otto: Military organization and the organization of the state, in: Gilbert, Felix (ed.): The historical essays of Otto Hintze, New York 1975: Oxford University Press, pp. 175-215.

- Hobson, J. A.: The psychology of jingoism, London 1901: Grant Richards.

- Howard, Michael: War in European history, New York 2009: Oxford University Press.

- Huntington, Samuel P.: The soldier and the state. The theory and politics of civil-military relations, Cambridge 1957: Harvard University Press.

- Kennedy, Paul / Nicholls, Anthony (eds.): Nationalist and racialist movements in Britain and Germany before 1914, London 1981: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lasswell, Harold D.: Sino-Japanese crisis. The garrison state versus the civilian state, in: The China Quartely 2, 1937, pp. 643-649.

- Paris, Michael: Warrior nation. Images of war in British popular culture, 1850-2000, London 2000: Reaktion Books.

- Pennell, Catriona: A kingdom united. Popular responses to the outbreak of the First World War in Britain and Ireland, Oxford 2012: Oxford University Press.

- Perlmutter, Amos: The military and politics in modern times. On professionals, praetorians, and revolutionary soldiers, New Haven 1977: Yale University Press.

- Rüger, Jan: The great naval game. Britain and Germany in the age of empire, Cambridge; New York 2007: Cambridge University Press.

- Spencer, Herbert: The principles of sociology, 3 volumes, London 1876-1896: Williams and Norgate

- Summers, Anne: Militarism in Britain before the Great War, in: History Workshop Journal 2, 1976, pp. 104-123.

- Vagts, Alfred: A history of militarism. Civilian and military, Westport 1981: Greenwood Press.

- Verhey, Jeffrey: The spirit of 1914. Militarism, myth and mobilization in Germany, Cambridge; New York 2006: Cambridge University Press.