Introduction↑

The Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) was, on the eve of World War I, the largest party in the German Reich, with about 1 million members, and also the largest party in the German parliament (the Reichstag), with 110 of 397 deputies. During World War I, it experienced its worst crisis, which resulted in the split of the party in 1917.

War loans and the “truce” policy↑

Until the beginning of the war, the party was fundamentally opposed to the imperial class state and was widely ostracized socially. Although the party leadership had called for anti-war protests just before the outbreak of the war, the parliamentary party of the SPD decided, on 3 August 1914, with a clear majority, to approve war credits. The next day, the SPD unanimously voted for the granting of war loans in the Reichstag. The “politics of the 4th of August” (Politik des 4. August) induced the truce (Burgfrieden), which led to the abandonment of the hitherto advocated class struggle. The reason for this was the belief that the war against Tsarist Russia was defensive. The Social Democrats had always been known for their policy of national defense. Additionally, they hoped to receive long-denied political recognition.

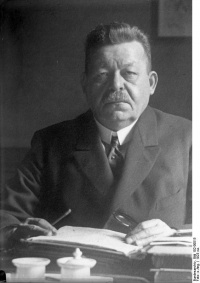

The integration of the SPD in the nation with the “politics of the 4th of August” led to an intra-party conflict. The majority, under the leadership of one of the two party chairmen, Friedrich Ebert (1871-1925), stuck to the chosen course. However, the number of members of parliament (MPs) in the fraction that argued against the provision of war loans continuously grew:

| August 1914 | 78 yes/14 no |

| November 1914 | 82 yes/17 no |

| March 1915 | 77 yes/23 no |

| August 1915 | 72 yes/36 no |

| December 1915 | 66 yes/44 no |

In opposition to the truce, two lines of thinking took shape: the radical Spartacus group branded the “standstill” policy as a betrayal of the Socialist International and continued to support the revolutionary class struggle. A moderate minority, led by the other chairman, Hugo Haase (1863-1919), also rejected the truce, but would basically maintain party unity and win the majority in the group and the party.

Split of the party↑

The basic disagreement revolved around the principle of subordination of the minority to resolutions passed by majority. This was the explosive device. In December 1914, Karl Liebknecht (1871-1919) was the first to vote against the new loans in the Reichstag. More and more politicians broke with party discipline, which they had initially followed but increasingly felt was a constraint. In December 1915, after a statement in the Reichstag against the truce, twenty MPs from the SPD opposed the war loans in parliament. The party leadership refused to exclude dissenters, a move which the right-wing MPs of the SPD demanded. However, the deep fragmentation could only be stopped temporarily. When, in March 1916, the opposition rejected the Notetat (emergency budget) in the Reichstag after a speech from Haase, although they had previously decided, with forty-four against thirty-six, for its assumption, the opposition split off into an independent fraction. Under the leadership of Haase, the minority formed the "Social Democratic Working Group" (Sozialdemokratische Arbeitsgemeinschaft).

This separation was followed by a bitter intra-party struggle, which ended in the founding of the “Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany” (Unabhängige Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands, or USPD) in April 1917, which was first joined by the Spartacus group. The cleavage did not take place along the pre-war lines of demarcation, which ran between revolutionary and reformist forces of the party. Thus, the Marxist theoretician Karl Kautsky (1854-1938) as well as the leading revisionist Eduard Bernstein (1850-1932) joined the USPD, while some pre-war radicals stayed in the majority.

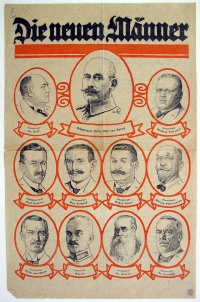

After the cleavage, the Majority Social Democrats (MSPD) forced the other parties to cooperate and formed, in June 1917, with the Catholic Centre Party and the left-liberal Progressive Party, the “Intergroup Committee” (Interfraktioneller Ausschuss). The isolation of the MSPD was, with this informal parliamentary committee, broken. This was an important transitional stage on the way to becoming a ruling party. However, the cooperation of the MSPD with the bourgeois parties had no concrete results. The strong demand for political and social reforms remained unmet. Nevertheless, the MSPD participated, in October 1918, in the first parliamentary national government under Prince Max von Baden (1867-1929). Before the final whistle, the MSPD succeeded in realizing a series of constitutional amendments: parliamentary control and the foreign and military policy, ministerial responsibility, and – an old social-democratic demand – the abolition of the Prussian three-class voting system in favor of democratic and general elections. However, these reforms came too late. The revolution destroyed the hope of a gradual transition to democracy.

Revolution↑

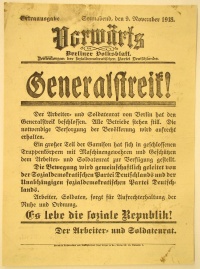

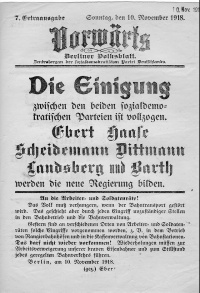

After the outbreak of the revolution in November 1918, the two social democratic parties temporarily cooperated in the Council of People's Commissars of the revolutionary government (Rat der Volksbeauftragten) before fundamental disagreements about the design of the Republic tore up the old trenches again and the USPD left the Revolution Cabinet at the end of December 1918. In December 1920, the left wing merged with the Communist Party of Germany (Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands, or KPD), which was founded at the end of 1918 by the Spartacists and other radical groups, while the right wing USPD reunited with the MSPD in September 1922. The SPD and KPD remained irreconcilable until the end of the Weimar Republic.

Walter Mühlhausen, Stiftung Reichspräsident-Friedrich-Ebert-Gedenkstätte

Section Editor: Christoph Jahr

Selected Bibliography

- Berger, Stefan: Die Parteispaltung während des Ersten Weltkrieges, in: Faulenbach, Bernd / Helle, Andreas (eds.): Menschen, Ideen, Wegmarken. Aus 150 Jahren deutscher Sozialdemokratie, Berlin 2013: vorwärts, pp. 52-61.

- Kruse, Wolfgang: Krieg und nationale Integration. Eine Neuinterpretation des sozialdemokratischen Burgfriedensschlusses 1914/15, Essen 1993: Kartext Verlag.

- Miller, Susanne: Burgfrieden und Klassenkampf. Die deutsche Sozialdemokratie im Ersten Weltkrieg, Düsseldorf 1974: Droste.

- Mühlhausen, Walter: Die Sozialdemokratie am Scheideweg. Burgfrieden, Parteikrise und Spaltung im Ersten Weltkrieg, in: Michalka, Wolfgang (ed.): Der Erste Weltkrieg. Wirkung, Wahrnehmung, Analyse, Munich 1994: Piper, pp. 649-671.