↑

German battleship building and Weltpolitik opened the door to the Anglo-German naval race. Driven by a desire to make the German Empire a viable world power and an integral industrial nation, the Navy Bills of 1898 and 1900 laid out the course for a massive naval expansion under anti-British auspices. The completed navy was to have a real fighting chance in a defensive war against the Royal Navy in the North Sea, with a projected German-British force ratio in capital ships of 2:3. Designed as a military deterrent against an empire that allegedly held the key to Germany’s future, this fleet would serve as a geopolitical lever to coerce Britain into accepting the German bid for equality as a global empire, or so the architect of this strategy, Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz (1849-1930), reasoned.

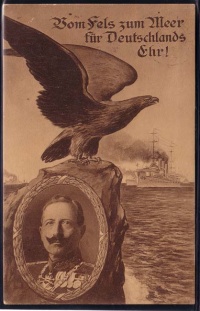

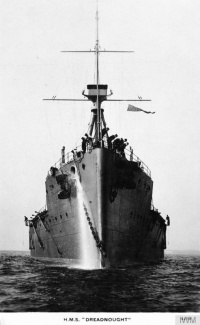

The German naval buildup unfolded methodically, carefully managed by the Imperial Naval Office, supported by a fleet-loving emperor and the empire’s political leadership, sustained by the naval enthusiasm of Germany’s bourgeois intelligentsia, and supported by a broad section of the political nation. It was then left to Tirpitz, Wilhelm II, German Emperor (1859-1941), and Chancellor Bernhard von Bülow (1849-1929) between 1905 and 1908 to bring the German challenge to British naval power out into the open and to usher in the era of an open naval race. Confronted with the dramatic change in capital ship construction associated with the “Dreadnought” battleships and battle cruisers pioneered by the Royal Navy, the Germans first incorporated the construction of these new ship types into their existing program in the Navy Bill of 1906, with its annual building rate of three large ships. They then transitioned to an annual rate of four capital ships over the next four years in the Navy Bill of 1908.

British naval policy-makers quickly took note of the German program and its anti-British intentions. But until well after 1906, British naval strategy and building policy were driven by other threat assessments (feared confrontations with France and Imperial Russia) and commitments (maintenance of global military capabilities, financial limitations, and the search for military-technological innovations beyond the paradigm of battlefleet warfare). Only subsequently, after the passage of the German Navy Bills of 1906 and 1908 and in the wake of the destruction of Russian sea power in the Russo-Japanese War and the diplomatic realignments of 1904-1907, did considerations of German armaments and capabilities emerge as a primary factor in British naval decision-making and public debate. By 1908, British naval construction, deployment, and war-planning took heed of the battleships being built on the other side of the North Sea, even as they also continued, until the outbreak of war in 1914, to reflect broader commitments to the global defense of the British imperial realm against all adversaries.

↑

The Anglo-German naval race came into focus with the German Navy Bill of 1908 and the British “Navy Scare” of 1909, which resulted in a massive construction program under anti-German auspices. An atmosphere of mutual suspicion now ruled the day. German fear of an imminent British military strike was matched by British suspicion about a secret acceleration of the construction of German capital ships. With broad national support, the British political and military leadership forcefully responded to the German program and displayed a relentless determination to protect British naval mastery. After 1908, massive British naval construction ensured the perpetuation of a favorable force ratio. The Liberal government also showed its resolve to increase its armaments supply with the passing of the so-called People’s Budget, which raised new revenue through taxation and suggested that Britain was in a position to mobilize whatever financial resources were necessary to remain ahead in the naval race with Germany, even at the expense of a constitutional crisis. In the years leading up to 1914, the Royal Navy retained its position of clear maritime superiority; its war planners developed schemes for a war with Germany involving a naval blockade and economic warfare. The Germans could not hope to match the British response. To raise new revenue to cover ever-escalating expenses for naval construction proved increasingly difficult, due to structural domestic political impediments. Furthermore, an ever-growing chorus of critics within and outside the government rapidly emerged. They emphasized British financial superiority and the deleterious diplomatic consequences of the Anglo-German antagonism, while also arguing for Germany to once again prioritize land power over the navy. The arms race was decided almost as soon as it started, as clear-headed observers in Germany and Britain recognized right away. (Indeed, the British would eventually enter World War I with forty-five “Dreadnought” battleships and battle cruisers in service or under construction, whereas the Germans would do so with twenty-six such ships built or in the process of being built.) But until 1914, German navy leaders struggled to face the facts and to declare a lost arms race lost.

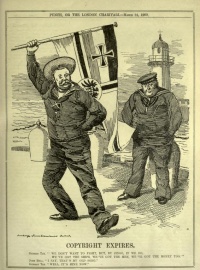

The Anglo-German arms race saw repeated attempts to explore the possibility of an arms control agreement. These talks, which included a visit by the British Secretary of War Richard Burdon Haldane (1856-1928) to Berlin in February 1912, never stood a chance of succeeding, as both sides were unwilling to enter into an agreement to their disadvantage. In Germany, Tirpitz enjoyed a veto position that allowed him to torpedo any efforts at a mutually acceptable agreement with Britain, which were undertaken by successive chancellors and supported by most of the civilian foreign policy elite in an effort to improve Anglo-German relations. In Britain, interest in an arms agreement was driven by a desire to stabilize naval competition at as low a level as possible in order to limit the financial costs of maintaining a clear British superiority. The Anglo-German talks that took place while the German Navy Bill of 1912 was being considered shattered any hopes in that regard for good. Subsequent talk about “naval holidays” and mutual arms limitations served a strictly propagandistic purpose.

In each country, the essentials of the naval build-up ultimately remained non-negotiable. This reflected the thinking of the decision-making elites, but it was also underwritten by the pressures of fast-developing naval-industrial complexes and their protagonists in politics and the press. Any substantive reduction of armaments appeared problematic in light of the direct consequences for the particular industries involved and the repercussions for national economies. More importantly, the naval competition galvanized political parties and the broader public and attracted the attention of the fast-developing mass media. In each country, the pursuit of maritime force became a focal point of political mobilization, public debate, and nationalist identity politics. Political parties rallied around the case for national power, global empire, and maritime force, making the possession of a first-rate navy an attribute of a strong nation, well beyond the particulars of force ratios and maritime strategy.

Another key component of the naval race was the rise of broader cults and folkloric appropriations of the navy, promoted by (but not limited to) the British and German navy leagues. Popular enthusiasm and media coverage developed in particular around the public staging of the navy in the form of fleet reviews and ship launches, which became performative displays of power and deterrence. These displays, in turn, directly fed Anglo-German enmity through their ostentatious character; their linkage of national identity, the sea, and military power; and the rituals’ own peculiar rhetoric and choreography of rivalry. Located at the intersection of popular culture, mass politics, and personal longings, this “naval theatre” (Jan Rüger) imbued the competition over sea power with symbolic meanings that transcended the calculations of policy-making elites and nourished a culture of public enmity and armed nationalism even after the arms race itself had been decided in Britain’s favor.

Legacies↑

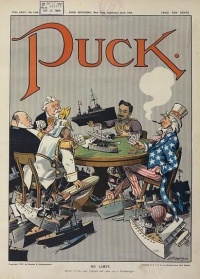

The Anglo-German naval race heightened the tensions between the German and British Empires and cast a long shadow over their pre-war diplomacy. To be sure, the race was decided early on; political leaders and diplomats learned to bracket it as an issue, and it did not cause the decision for war in 1914. But the naval competition nonetheless created an atmosphere of mutual hostility and distrust, which circumscribed the space for peaceful diplomacy and public recognition of shared interests, and helped to pave the twisted road to war in Europe. The race’s outcome fed the panic among German elites over the prospect of Germany losing its place as a world power. This, in turn, provided a necessary condition for the German policy of brinkmanship in July 1914, which ultimately made war inevitable. On the British side, thinking about the German naval challenge colored the decision to go to war over Germany’s invasions of Belgium and France. The pre-war culture of conflict then easily turned into intense wartime hostility, a mutually reinforcing regime of British Germanophobia and German Anglophobia combined with the totalizing conditions of a war cast as a clash of civilizations. To view the Anglo-German arms race as a direct precursor of the war and both as part of a developing Anglo-German antagonism became common in each country, with German Anglophobes going so far as to denounce the British Empire as the main instigator of the war. Foreign observers, especially in the United States, were also prone to draw a direct line from the arms race to a war and to view the latter as a product of the pre-war Anglo-German conflict over navies and empire.

Ever since, the arms race has loomed large in public narratives and memory of the lead-up to World War I. Over time it has increasingly come to stand in either for the folly of pre-war militarism and power politics as a general European condition, or for both the pathology of the German bid for world power, linked to the country’s compromised modernity, and the superior rationality of Britain as a liberal state and peaceful empire. In the era of Cold War militarization and U.S.-Soviet antagonism, the Anglo-German arms competition also served as an object lesson for the concerned public, allegedly providing insight into the dynamics of a modern arms race and the relationship between threat, deterrence, and war. In the past twenty-five years, however, the story of the Anglo-German race has lost its luster as a cautionary tale as Europe confines its 20th century to history and confronts a present not haunted by the specter of big power arms competitions and war. Strikingly, there has been a sustained effort to rethink the Anglo-German arms race as a historical event, at least in the scholarly realm. While scholars of German Weltpolitik and battleship construction continue to stress the seriousness of the German challenge to British naval mastery and the reality of the arms competition, many historians of the Royal Navy and the British Empire have come to downplay the centrality of the arms race and the larger Anglo-German antagonism for the understanding of British naval policy and strategy before 1914. Today, the place of the Anglo-German naval race in the historical imagination of the future remains an open question.

Dirk Bönker, Duke University

Section Editor: Christoph Nübel

Selected Bibliography

- Berghahn, Volker R.: Germany and the approach of war in 1914, New York 1973: St. Martin's Press.

- Bönker, Dirk: Militarism in a global age. Naval ambitions in Germany and the United States before World War I, Ithaca 2012: Cornell University Press.

- Hobson, Rolf: Imperialism at sea. Naval strategic thought, the ideology of sea power, and the Tirpitz Plan, 1875-1914, Boston 2002: Brill Academic Publishers.

- Kennedy, Paul M.: The rise of the Anglo-German antagonism, 1860-1914, London; Boston 1980: Allen & Unwin.

- Lambert, Nicholas A.: Sir John Fisher's naval revolution, Columbia 1999: University of South Carolina Press.

- Massie, Robert K.: Dreadnought. Britain, Germany, and the coming of the Great War, New York 1991: Random House.

- Rüger, Jan: The great naval game. Britain and Germany in the age of empire, Cambridge; New York 2007: Cambridge University Press.