Introduction↑

During the course of the 19th century Britons developed complex views of Germany, which became increasingly negative as the First World approached, epitomised by the rise of spy-fever and the birth of the spy novel.[1] However, following the outbreak of war, the hatred of the “Hun” reached new levels, as Britons learnt to hate,[2] perhaps for the first time, as their country crossed a threshold in its national consciousness and developed a unity in which the German became the antithesis of British values.[3]

Wartime Hatred↑

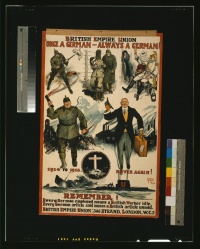

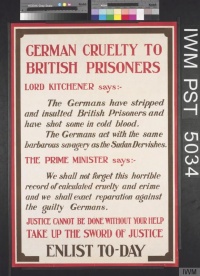

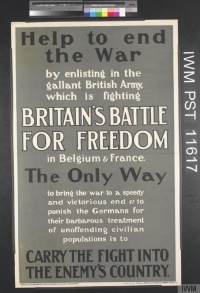

British propaganda, both official and unofficial, played a central role in the development of the negative image of the outsider. This representation constructed the Germans as brutes and economic rivals in particular,[4] a process in which academics played a role.[5] While the latter fear had begun to develop before 1914, the former took off following the German invasion of Belgium and, even more so after the sinking of the Lusitania, when newspapers carried headlines such as, “No Compromise with a Race of Savages” and “The Branded Race”.[6] Against this background, spy-fever and spy novels also developed and played a large role in the hatred of Germany.[7]

Apart from the peddling of images of the “evil Hun”, Germanophobia had more concrete consequences. In the first place, it resulted in an avoidance of all things German. For example, the Henry Wood Promenade Concerts at the Albert Hall tried to ban German music, although this became unsustainable because of the impact on the classical repertoire. Meanwhile, at the end of the Great War, Leicester City Council changed the names of a series of streets in the Highfields area of the city named after the family of Victoria, Queen of Great Britain (1819-1901) and her husband Albert, Prince Consort, consort of Victoria, Queen of Great Britain (1819-1861), with Saxe-Coburg Street becoming Saxby Street and Mecklenburg Street renamed Severn Street.[8]

At the same time, the British Empire, in common with the other Allied states, launched an economic war against the Germans, which resulted in the confiscation of German property throughout the world, with no recourse to compensation: in fact, the sequestered property contributed towards the reparations payments under the Treaty of Versailles. Images of the German economic Octopus with its tentacles spread all over the world fuelled such actions.[9]

Those Germans who found themselves living in Britain bore the brunt of the hostility. The spy-fever of the Edwardian period developed into a theory of a “hidden hand” which controlled Britain and prevented victory.[10] Anyone with German connections faced hostility, including the Royal Family, which changed its name from Saxe-Coburg to Windsor in 1917.[11] The War Secretary Richard Burdon Haldane (1856-1928), found himself hounded out of office at the start of the war because he had once described Germany as his spiritual home and had studied in the country.[12] The German born Sir Edgar Speyer (1862-1932), who had helped to build the London underground, left Britain, rather than continue to face hostility.[13] More humble Germans faced even worse animosity resulting in a loss of employment. At the same time the Aliens Restriction Act imposed severe restrictions upon movement for Germans and also closed down German clubs. This measure, together with property confiscation, widespread anti-German riots, which peaked following the sinking of the Lusitania in May 1915 when virtually every German owned shop in Britain faced attack, and mass deportation (preceded by deportation of German born males of military age), destroyed the vibrant German community which had emerged in the Victorian and Edwardian years.[14]

Conclusion↑

Against this background, the admiration for Germany, which had characterised the Victorian era in particular, disappeared. Germanophilia became impossible because of the press obsession with, and hatred of, all things German, although a few organizations, above all the Society of Friends, did assist both German internees and their families who remained at liberty. At the same time, a few liberal MPs, such as Joseph King (1860-1943) and Josiah Wedgewood (1872-1943), stood up for the Germans in Britain in the House of Commons.[15] But these remained lone voices facing the screeching choir of British nationalism whose nationalist ideology fed off the German enemy.

Panikos Panayi, De Montfort University

Section Editor: Catriona Pennell

Notes

- ↑ Panayi, Panikos: German Immigrants in Britain during the Nineteenth Century, Oxford 1995, pp. 201-51.

- ↑ The phrase “Learning to Hate” is used as the title of Chapter 4 of Paxman, Jeremy: Great Britain's Great War, London 2013.

- ↑ Pennell, Catriona: A Kingdom United. Popular Responses to the Outbreak of the First World War in Britain and Ireland, Oxford 2012.

- ↑ Haste, Cate: Keep the Home Fires Burning, London 1977; Messinger, Gary S.: British Propaganda and the State in the First World War, Manchester 1992.

- ↑ Wallace, Stuart: War and the Image of Germany. British Academics, 1914-1918, Edinburgh 1988.

- ↑ Panayi, Panikos: The Enemy in Our Midst. Germans in Britain During the First World War, Oxford 1991, pp. 223-34.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 153-62, 223-34.

- ↑ Highfields, Leicester: Germanophobia Led to of Renaming Streets, issued by the BBC, online: http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p022x7b3 (retrieved 11 November 2014).

- ↑ Panayi, Enemy 1991, pp. 132-49.

- ↑ Panayi, Panikos: “The Hidden Hand.” British Myths About German Control of Britain During the First World War, Immigrants and Minorities, 7 (1988), pp. 253-72.

- ↑ Nicolson, Harold: King George V. His Life and Reign, London 1952, pp. 307-10.

- ↑ Panayi, Enemy 1991, pp. 184-185.

- ↑ Lentin, Antony: Banker, Traitor, Scapegoat, Spy? The Troublesome Case of Sir Edgar Speyer, London 2013.

- ↑ Panayi, Enemy 1991, pp. 45-258.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 259-91.

Selected Bibliography

- Haste, Cate: Keep the home fires burning. Propaganda in the First World War, London 1977: Allen Lane.

- Lentin, Antony: Banker, traitor, scapegoat, spy? The troublesome case of Sir Edgar Speyer. An episode of the Great War, London 2013: Haus Publishing.

- Panayi, Panikos: The enemy in our midst. Germans in Britain during the First World War, New York 1991: Berg; St. Martin's Press.

- Pennell, Catriona: A kingdom united. Popular responses to the outbreak of the First World War in Britain and Ireland, Oxford 2012: Oxford University Press.

- Wallace, Stuart: War and the image of Germany. British academics, 1914-1918, Edinburgh 1988: J. Donald Publishers.