The British press has sometimes been depicted as a compliant tool of the wartime government, eager to assist with propaganda and willingly self-censoring sensitive content. "The Harlot of Fleet Street", Gerard De Groot suggests, "sold herself cheaply".[1] Government propaganda has also been derided as both shambolic and sinister, producing overblown accounts of atrocities which, nonetheless, supposedly tricked the public into endorsing the war and the increasing restriction of civil liberties.[2] However, more recent interpretations show that the press could act with considerable autonomy despite censorship and that propaganda was more sophisticated and less exclusively sensationalist than once thought.

The Press as a business↑

In 1914, the British press featured a vibrant assortment of metropolitan, provincial and specialist newspapers. Despite a one-third reduction since 1904, London had fourteen "major metropolitan dailies", ranging from establishment papers like The Times to newer, cheaper and more popular titles like the Daily Mail, Daily Express and Daily Mirror.[3] These were supplemented by periodicals such as the right-wing National Review, Henry William Massingham’s (1860-1924) trenchantly critical Liberal weekly The Nation and the Independent Labour Party’s (ILP) Labour Leader. Provincial cities also featured several titles; Leicester (with a wartime population of around 230,000) maintained two daily and five weekly papers in 1918.[4] "To a considerable extent", Stephen Koss argues, "the power of the press was a conceit on the part of journalists", but one encouraged and exploited by proprietors like Alfred Charles William Harmsworth, Lord Northcliffe (1865-1922), owner of the Times and Daily Mail, and Max Aitken, Lord Beaverbrook (1879-1964), owner of the Daily Express, and by politicians eager to cultivate support.[5]

The Defence of the Realm Act and the Press Bureau↑

Efforts to control press activities began before the war, when the Admiralty, War Office, and Press Committee convened on 27 July 1914 and press representatives were asked not to publish naval or military information. Sir George Riddell (1865-1934), owner of the News of the World, assured officials that he was "confident that the Press would publish nothing detrimental if asked to be silent", and a letter was sent the same evening, asking editors to clear references to unusual military or naval movements with the Admiralty or War Office. Such restrictions became increasingly formal as the Defence of the Realm Act (DORA) made revealing military information a punishable offence and a Press Bureau (PB) was established on 6 August. From late August, the PB issued "D" Notices to an increasingly large list of metropolitan and provincial papers, specifying topics that should not be published or should be withheld until a certain time. Riddell, Deputy-Chairman of the Newspaper Proprietors’ Association (NPA), lamented press timidity towards DORA, "which wipes out Magna Carta, the Bill of Rights, etc., in a few lines."[6] His regular correspondence with the PB during the war charted the frustrations endured by NPA members, including very late announcement of information, affecting publication deadlines, and excessive placement of official notices, articles and photographs, which some newspapers saw as attempts to gain free advertising and monopolise revenue.[7] Nonetheless, the PB’s relationship with newspapers improved as notifications and mutual understanding became more sophisticated.

Censorship and self-censorship↑

DORA and the PB’s strictures did not mean that no information about the immediate state of the war reached the public. Newspapers were technically free to publish anything not restricted by "D" Notices, and could voluntarily submit copy for clearance. The PB did not formally censor newspapers, but advised about the possible risk of prosecution when consulted. Editors faced a delicate balance between publishing material that might be sensitive and risk prosecution, or self-censoring too scrupulously and allowing rivals to appear better informed. They also had to consider their readers’ needs. Though details of local regiments’ actions were prohibited, Liverpool’s newspapers frequently published soldiers’ letters giving revealing details. As Helen McCartney notes, suggestions that civilians were oblivious to servicemen’s experiences and views are disproved by local newspapers.[8] Nor was critical commentary generally prohibited. John A. Hobson’s (1858-1940) pseudonymous satires of DORA, propaganda and other topics were published over several weeks in 1917 in The Nation without hindrance. While Brock Millman ascribes permissive responses to criticism to a wish to appear liberal while curtailing liberty, the Prime Minister, David Lloyd George (1863-1945), suggested "nobody cared" what was published in the Nation because it was notorious for fault-finding.[9]

Newspapers could suffer formal punishments if they overstepped the mark – the Globe was suppressed for two weeks in 1915 after publishing a false report about Horatio Herbert Kitchener’s (1850-1916) imminent resignation, while some papers, including the Labour Leader, the Nation and several Irish papers, were prohibited from overseas distribution. However, on other occasions, editors decided for themselves that material was inappropriate. The Daily Mail’s criticism of the "shell scandal" in 1915 caused a substantial drop in circulation, while the Daily Telegraph’s publication in November 1917 of Henry Petty-Fitzmaurice, Marquess of Lansdowne’s (1845-1927) letter calling for clearer war aims also drew substantial criticism. Another factor inhibiting discussion was the increasing shortage of paper. Newspapers, especially provincial papers, which had often already shed popular sections like the "woman’s page" or sports pages as perceived frivolities, were sometimes reduced to as little as four pages. With many papers still printing large numbers of advertisements on their front page, verbatim reports of local speeches, and leaving space for memorials for servicemen, there was often little room for wider reflections.

In Ireland, suppression of critical newspapers was more common, and issues of several newspapers were seized in December 1914 after warnings about publishing "seditious" material. Thereafter, radical nationalist newspapers were closely monitored. Arthur Griffith (1872-1922) attempted to subvert censorship through his newspaper Scissors and Paste, which arranged cuttings from British newspapers to present a negative portrait of Britain. Despite the Chief Secretary for Ireland questioning the need to act, Scissors and Paste ran for only three months before being suppressed in March 1915. In other cases, less stringent penalties including warnings, seizures or dismantlement of equipment were used.[10]

PB oversight was replaced by a special Press Censorship Office after the 1916 Easter Rising. Nonetheless, post-Rising censorship was reportedly fairly restrained, relying on threats of suppression if newspapers overstepped reasonable bounds rather than routine censorship. While positive comments about the Rising were restricted, some papers successfully published positive material, such as the moderately-worded Catholic Bulletin, while the Censor was also reluctant to act against the Irish Parliamentary Party’s moderate Freeman’s Journal. Moreover, some events, like the 1918 opposition to Irish conscription, were too widespread to censor without mass suppression. Thus, while radical newspapers faced greater restrictions than their British counterparts, it remained possible to display some level of anti-establishment sentiment.[11]

The Press, politics and war correspondents↑

The press largely accepted calls for restraint and demonstrated this by self-censoring sensitive materials and making editorial choices about appropriate content. Despite its reputation for atrocity-mongering, the Daily Mail more often described destruction of property than crimes against people, most frequently discussing violence against civilians when provided with official information.[12] Nonetheless, the press retained political influence, not least because the political truce agreed by the main parties muted politicians’ airing of partisan differences. Newspapers and periodicals became vehicles for continuing political disputes indirectly. Several of the war’s largest political controversies featured considerable press involvement.

The Shells Scandal↑

In 1914 the War Secretary, Kitchener, prohibited war correspondents from the Western Front, irritating newspaper-owners who were denied access to the latest information. In May 1915, after prolonged pressure, Kitchener finally relented and allowed correspondents to appear. Around the same time, Northcliffe warned Britain’s Commander-in-Chief, Sir John French (1852-1925), of his suspicions that French would be blamed for military failure. Following Northcliffe’s advice, French spoke to the Times’ correspondent on the Western Front, Charles Repington (1858-1925), who then blamed the failed assault on Aubers Ridge on inadequate munitions.[13] In the ensuing controversy, the first Coalition government was formed, but Kitchener, who Northcliffe blamed for munitions problems, remained War Secretary, prompting an attack by the Mail and a subsequent backlash against Northcliffe and his newspaper. Ultimately, Lloyd George became Minister of Munitions and reorganised production. J. Lee Thompson suggests Northcliffe attained few of his ambitions. Herbert Henry Asquith (1852-1928) remained Prime Minister and Kitchener remained War Secretary – the controversy thus contributed to the shift toward a coalition government but was not solely responsible, and political and military trust in press responsibility declined.[14] However, war correspondents, alongside official artists, photographers and film-makers, remained at the Front.

Lloyd George and the Press Lords↑

Lloyd George had scored political points via the press long before 1914. His influence in May 1915 was suspected by many, and he retained close connections with several proprietors, editors and journalists. Such relationships were not always cosy – Lloyd George and Northcliffe’s connections were strained by Northcliffe’s consistent support for Sir Douglas Haig (1861-1928) in debates over the war’s proper direction. His papers were thus partially excluded from information in the days preceding Asquith’s replacement as Prime Minister in December 1916. Lloyd George’s contacts with the Conservative Party were aided by Aitken, while Riddell and Edward Levy-Lawson, Baron Burnham (1833-1916) (owner of the Telegraph) were also well-informed. Nonetheless, Northcliffe and his papers, briefed by the Irish Unionist Edward Carson (1854-1935) and others, supported Asquith’s removal. So strong was distrust of Lloyd George’s press links that Conservative support for Lloyd George’s elevation required a promise that Northcliffe would not receive a Cabinet post.

Once Prime Minister, Lloyd George made efforts to ensure the goodwill of the most influential press figures. Seeking to reorganise propaganda, he arranged for a Press Advisory Committee involving Northcliffe, Riddell, Burnham and the newly ennobled Beaverbrook to discuss the issues, and commissioned the Daily Chronicle’s editor, Robert Donald (1860-1933), to report on existing propaganda arrangements. Beaverbrook and Northcliffe were later appointed to major propaganda positions, not only because of their expertise, but also because it was hoped this would keep them busy and inhibit criticism.[15]

The Maurice Affair↑

Germany’s 1918 spring offensive provoked another confrontation between politicians and the press, and demonstrated the limits of Lloyd George’s attempt to corral press support. Once again, the issue was political interference in military matters. On 7 May, reportedly on Repington’s advice, the Director of Military Operations, General Frederick Maurice (1871-1951), denounced the government in the Times for withholding men and resources from the army. This provoked a Parliamentary debate in which Asquith and his allies bungled an attempt to unseat the government. However, it also encouraged a "calculated provocation" by Donald, who appointed Maurice the Chronicle’s military correspondent. Donald, suspicious of Lloyd George’s attempts to acquire control of the Chronicle, wished to align his paper with the Army. However, irked by the Chronicle’s increasing criticism, Lloyd George arranged for its purchase by sympathisers and the departure of Donald, which was completed in October. Riddell noted that Lloyd George, the sitting Prime Minister, would have "full control of the editorial policy...The experiment will be interesting."[16]

The local press and politics↑

Political controversy was not confined to national dailies. A prolonged local press campaign was mounted against one of Leicester’s MPs, James Ramsay MacDonald (1866-1937). Extending a propaganda campaign that began in April 1918 and ended with a near-riot in early May, a substantial dispute was continued in the pages of Leicester’s newspapers. While the ILP-linked Pioneer condemned the campaign as an outside job inspired by propagandists, other papers demanded MacDonald’s resignation. Local residents filled the correspondence pages for days with conflicting views, some condemning MacDonald’s dissent, others defending the right to alternative viewpoints. While MacDonald did not resign, he was defeated in 1918 and continued his career elsewhere.[17]

Government Propaganda↑

Though Britain and Ireland were involved in national war efforts, recent work has shown that, just as the content of local newspapers provides a more complicated picture of wartime attitudes than national dailies, locality was also crucial to propaganda’s success. While central organisations coordinated national efforts, in an era before mass home media messages were still delivered locally and, whether concerned with military recruitment, patriotic fundraising, appeals for war workers, or attempts to maintain morale and consent, featured both organisation and presentation by local people. Such approaches contextualised larger issues in their immediate setting and permitted active participation in, rather than passive reception of, propaganda and its purposes. Detailed investigation shows that propaganda was more nuanced and effective than earlier accounts allowed.[18]

The development of official propaganda↑

Propaganda was not yet a dirty word in 1914. It had more neutral connotations as the dissemination of information and arguments. Preoccupation with discrediting the least reputable forms of "black" propaganda, particularly excessive atrocity stories, created a post-war understanding of propaganda as fundamentally dishonest. Such interpretations, however, give too much credit to the wartime state’s organisational competence. Before 1917, at least, propaganda was insufficiently managed to be capable of mass manipulation. Even Lloyd George’s reorganisations from 1917 did not produce a seamless propaganda machine. Dystopian accounts of propaganda’s all-pervading influence appear misleading.

Initially, the two most important official organisations were the Parliamentary Recruiting Committee (PRC), which organised recruitment propaganda until the introduction of conscription in 1916, and the Foreign Office’s War Propaganda Bureau (more commonly known by the name of its offices, Wellington House), which issued propaganda to neutrals and Britain’s Dominions. In 1916, the National War Savings Committee began promoting public investment in war savings, aimed at protecting Britain’s economy from disruption. After Lloyd George’s ascent, a Department of Information was established in 1917, directed by the novelist John Buchan (1875-1940), which acted as an umbrella organisation for various smaller official operations. From mid-1917, domestic civilian propaganda was undertaken by the semi-official National War Aims Committee (NWAC), while a second reorganisation in early 1918 saw the Department of Information replaced with a larger Ministry of Information under Beaverbrook and enemy propaganda directed at Crewe House by Northcliffe. Despite the trauma caused by the Easter Rising, propaganda efforts also continued to be made to stimulate support for the Irish war effort, as Catriona Pennell has recently shown.[19]

Recruitment propaganda↑

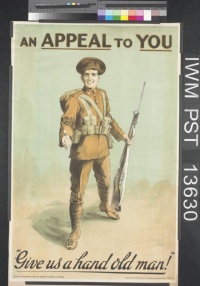

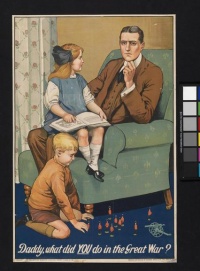

The most familiar aspects of British and Irish recruitment propaganda are the posters produced by the PRC, Central Council for Recruiting in Ireland and Department for Recruiting in Ireland. Older interpretations focus on supposedly typical posters like "Kitchener Wants You", "Daddy, What did You Do in the Great War?" or "Irishmen, Avenge the Lusitania". However, Nicholas Hiley shows that confrontational posters aiming to shame men into recruitment were actually less commonly used and effective than those emphasising participation and comradeship.[20] Further, while posters are visually striking, they were not the only method of communication. Street corner meetings, based on pre-war political activities, remained a staple element of wartime propaganda, while the PRC also experimented with film, projecting patriotic films from mobile "cinemotors", a practice continued by groups including the Ministry of National Service and the NWAC.

Atrocity propaganda↑

First World War propaganda is commonly associated with atrocities. Though it has been conclusively demonstrated that many atrocities occurred, propagandists used such events widely, partly to contextualise less dramatic aspects of the war effort. For instance, Nicoletta Gullace shows how British propagandists used atrocities to dramatise German diplomatic misconduct.[21] Wellington House publicised the Armenian genocide to both bolster British claims of fighting a war for civilisation and to distract US attention from Russian pogroms. Because atrocities so vividly depicted the war’s horrors, they were readily used to enliven propaganda appeals. However, despite its frequency, excessive attention to atrocity propaganda obscures the more complex messages conveyed.

Other methods and messages: Duty-based propaganda↑

The war’s most successful propaganda product was arguably Geoffrey Malins’ (1886-1940) film, The Battle of the Somme, released while the 1916 campaign continued and seen by approximately 19 million people in six weeks. While portraying the battle positively, it did not shy away from depicting British death and suffering.[22] In the war’s later years, domestic propaganda in Britain and Ireland focused on maintaining public endorsement of the war effort. Despite the hostility produced by the Easter Rising’s aftermath, propaganda was still directed at the Irish public in the hope of maintaining consent. Recruitment activities also continued since the government delayed, then abandoned, conscription in Ireland. In Britain, NWAC propaganda received active or passive support from the press. The NWAC placed articles in newspapers and contributed to a weekly War Supplement published in many provincial newspapers. A series of articles on "The Woman’s Part" showed the diversity of propaganda material. Atrocities were conspicuously absent, and the articles discussed women’s war work at home or elsewhere, particularly emphasising duty and service. Pennell suggests that dutiful acceptance and resolve, rather than enthusiasm, characterised most British and Irish people’s views in 1914, and the NWAC targeted similar attitudes later on.[23] However, propagandists also benefited from indirect newspaper coverage. Propaganda speeches were often reprinted at length, sometimes with accompanying editorials. Meetings attended by a few dozen people could thus be vicariously received by much larger audiences. Such speeches, while often mentioning atrocities, featured a much more complicated patriotic narrative revolving around duty and participation, while the repetitive staging of similar events operated on the basis of public familiarity with the format. Propagandists did not generally attempt to communicate in new and unusual ways, but to adapt established, familiar approaches to the wartime situation. National Service "War films" were accompanied by speeches, resolutions and votes of thanks in the same way as pre-war political meetings, emphasising that the messages contained in the new medium were serious rather than frivolous, and endorsed by local notables.[24]

Voluntary Organisations↑

Newspapers and the government were not the only purveyors of propaganda. Many voluntary organisations produced material that added to the wartime discussion of duty and national service. One reason for a better-organised official propaganda apparatus was to provide more coherent arguments to the public. While many unofficial groups had links with government or official organisations, it is important not to conflate their activities. In wartime, as in peacetime, many competing voices were heard, some reputable, others disreputable. NWAC speakers often clarified their organisational identity precisely because it distinguished them from unofficial groups. Before the 1917 reorganisation, groups like the Central Committee for National Patriotic Organizations, the Fight for Right Movement or the Victoria League filled gaps in official output with their own propaganda. Discharged servicemen’s groups also joined the clamour, as did charitable organisations promoting Belgian, Serbian or Armenian relief, soldiers’ comforts, the Red Cross and numerous other causes. Civilians were told they were fortunate to be relatively secure and prosperous in the British Isles and thus obliged to donate generously to charity or war savings. Later, organisations like the "patriotic labour" British Workers’ National League emerged, partially linked to government figures and committed to confronting – through force if necessary – the arguments and challenges of dissenting groups. Again, the press sometimes augmented such groups – the Daily Express, in particular, was accused of whipping up opposition to dissenting organisations.[25]

While most propaganda organisations (like most civilians) believed in the justice of the war, their means of showing support varied widely. Attempts to provide a single, monolithic description of the press or propaganda obscure more than they reveal. Newspapers were not universally subservient; propagandists were not universally manipulative purveyors of fabricated atrocities – public discussion of the war in the British Isles was much more complex.

David Monger, University of Canterbury

Section Editor: Adrian Gregory

Notes

- ↑ De Groot, Gerard J.: Blighty: British Society in the Era of the Great War, London 1996, p. 187.

- ↑ For example, Lasswell, Harold: Propaganda Technique in the World War, New York 1927; Ponsonby, Arthur: Falsehood in War-Time: containing an assortment of lies circulated throughout the nations during the Great War, London 1928; Haste, Cate: Keep the Home Fires Burning: Propaganda in the First World War, London 1977; Millman, Brock: Managing Domestic Dissent in First World War Britain, London 2000.

- ↑ Stephen Koss: The Rise and Fall of the Political Press in Britain, Volume 2: The Twentieth Century, Chapel Hill 1984, p. 1.

- ↑ The Newspaper Press Directory, London, 1918, pp. 145-6.

- ↑ Koss, Rise and Fall 1984, p. 7.

- ↑ Lord Riddell: Lord Riddell’s War Diary, 1914-1918, London, 1933, pp. 1-2; diary entry, 20 November 1914, p. 41.

- ↑ See the National Archives: Public Record Office, Kew, HO139/10/38, Press Bureau files, "Newspaper Proprietors’ Association". Some elements are reproduced in Riddell, Lord Riddell’s War Diary.

- ↑ McCartney, Helen B.: Citizen Soldiers: The Liverpool Territorials in the First World War, Cambridge 2005, pp. 104-17.

- ↑ For Hobson’s satires see, for example, The Nation, 27 Oct, 3 Nov and 24 Nov 1917. For Millman’s interpretation, see Managing Domestic Dissent, p. 78, and for Lloyd George’s comment of early May 1917 to the Manchester Guardian’s editor, Charles P. Scott (1846-1932), see Koss, Rise and Fall 1984, p. 312.

- ↑ Glandon, Virginia E.: Arthur Griffith and the Advanced-Nationalist Press: Ireland, 1900-1922, New York 1985, pp. 147-53.

- ↑ Ó Drisceoil, Donal: "Keeping disloyalty within bounds? British media control in Ireland, 1914-19", in: Irish Historical Studies, 38/149 (2012).

- ↑ Gregory, Adrian: "A Clash of Cultures: The British Press and the Opening of the Great War" in Paddock, Troy R.E. (ed.): A Call to Arms: Propaganda, Public Opinion, and Newspapers in the Great War, London 2004.

- ↑ Our Military Correspondent [Repington], "Need For Shells", Times, 14 May 1915, p. 8. The Times Digital Archive (accessed 19 Feb. 2014).

- ↑ Thompson, J. Lee: Politicians, the Press, and Propaganda: Lord Northcliffe and the Great War, 1914-1919, Kent 1999, pp. 27-8, 50-65.

- ↑ For fuller discussion of the incorporation of pressmen into propaganda, see especially Sanders, M.L. and Taylor, Phillip M.: British Propaganda during the First World War, 1914-18, London 1982, pp. 55-80.

- ↑ Turner, John: British Politics and the Great War: Coalition and Conflict 1915-1918, Oxford 1992, pp. 294-302; Koss, Rise and Fall, pp. 333-7; Riddell diary, 1 Oct 1918, in Riddell, Lord Riddell’s War Diary, p. 365.

- ↑ For a fuller account, see Monger, David: "Transcending the Nation: Domestic Propaganda and Supranational Patriotism in Britain, 1917-18" in Paddock, Troy R.E. (ed.): World War I and Propaganda, Leiden 2014, pp. 28-32.

- ↑ See especially Horne, John: "Remobilizing for 'Total War': France and Britain, 1917-1918" in Horne, John (ed.): State, society and mobilization in Europe during the First World War, Cambridge 1997; Purseigle, Pierre: "Beyond and Below the Nations: Towards a Comparative History of Local Communities at War" in Macleod, Jenny and Purseigle, Pierre (eds.): Uncovered Fields: Perspectives in First World War Studies, Leiden 2004; Monger, David: Patriotism and Propaganda in First World War Britain: the National War Aims Committee and Civilian Morale, Liverpool 2012; Pennell, Catriona: A Kingdom United: British and Irish Responses to the Outbreak of the First World War, Oxford 2012.

- ↑ For the evolution of British propaganda’s organisation, Sander and Taylor, British Propaganda, remains the best overview. For the most recent account of propaganda efforts in Ireland, see Pennell, Catriona: "Presenting the War in Ireland, 1914-1918", in Paddock, World War I and Propaganda.

- ↑ Hiley, Nicholas: ‘“Kitchener Wants You” and “Daddy, what did YOU do in the Great War?”: The Myth of British Recruiting Posters’, Imperial War Museum Review, 11 (1999). For recent discussions of recruiting posters, see Aulich, James and Hewitt, John: Seduction or Instruction? First World War Posters in Britain and Europe, Manchester 2007; Pennell, "Presenting the War in Ireland".

- ↑ Gullace, Nicoletta F.: "Sexual Violence and Family Honor: British propaganda and international law during the First World War", American Historical Review, 102/3 (1997).

- ↑ On The Battle of the Somme, and film propaganda more widely, see Reeves, Nicholas: Official British Film Propaganda during the First World War, London 1986; Hammond, Michael: "The Battle of the Somme (1916): An Industrial Process Film that 'Wounds the Heart'", in Hammond, Michael and Williams, Michael (eds.): British Silent Cinema and the Great War, Basingstoke, 2011.

- ↑ Monger, David: "Nothing Special? Propaganda and Women’s Roles in late First World War Britain", Women’s History Review 23/4 (2014); Pennell, A Kingdom United.

- ↑ TNA:PRO NATS1/110 – "Posters and Bills, M of N Service. Actual War Cinematograph Film. Displayed Throughout the Country".

- ↑ Sanders and Taylor, British Propaganda; Millman, Managing Domestic Dissent.

Selected Bibliography

- Aulich, James / Hewitt, John: Seduction or instruction? First World War posters in Britain and Europe, Manchester; New York 2007: Manchester University Press; Palgrave.

- Glandon, Virginia E.: Arthur Griffith and the advanced-nationalist press, Ireland, 1900-1922, New York 1985: P. Lang.

- Gregory, Adrian: The last Great War. British society and the First World War, Cambridge; New York 2008: Cambridge University Press.

- Gregory, Adrian: A clash of cultures. The British press and the opening of the Great War, in: Paddock, Troy R. E. (ed.): A call to arms. Propaganda, public opinion, and newspapers in the Great War, Westport 2004: Praeger Publishers, pp. 15-49.

- Gullace, Nicoletta F.: Sexual violence and family honor. British propaganda and international law during the First World War, in: The American Historical Review 102/3, 1997, pp. 714-747.

- Hiley, Nicholas: 'Kitchener wants you' and 'Daddy, what did YOU do in the Great War?' The myth of British recruiting posters, in: Imperial War Museum Review 11, 1999, pp. 40-58.

- Hopkin, D.: Domestic censorship in the first world war, in: Journal of Contemporary History 5/4, 1970, pp. 151-169.

- Horne, John (ed.): Remobilizing for 'total war'. France and Britain, 1917-1918, Cambridge 1997: Cambridge University Press, pp. 195-211.

- Koss, Stephen Edward: The rise and fall of the political press in Britain. The twentieth century, volume 2, Chapel Hill; London 1984: The University of North Carolina Press.

- Messinger, Gary S.: British propaganda and the state in the First World War, Manchester; New York 1992: Manchester University Press; St. Martin's Press.

- Millman, Brock: Managing domestic dissent in First World War Britain, London; Portland 2000: Frank Cass.

- Monger, David: Patriotism and propaganda in First World War Britain. The National War Aims Committee and civilian morale, Liverpool 2012: Liverpool University Press.

- Monger, David: Nothing Special? Propaganda and women’s roles in late First World War Britain, in: Women’s History Review 23/4, 2014, pp. 518-542.

- Ó Drisceoil, Donal: Keeping disloyalty within bounds? British media control in Ireland, 1914-1919, in: Irish Historical Studies 38/149, 2012, pp. 52-69.

- Pennell, Catriona: A kingdom united. Popular responses to the outbreak of the First World War in Britain and Ireland, Oxford 2012: Oxford University Press.

- Pennell, Catriona: Presenting the war in Ireland, 1914-1918, in: Paddock, Troy R. E. (ed.): World War I and propaganda, Leiden 2014: Brill, pp. 42-64.

- Riddell, Baron George Allardice Riddell: Lord Riddell's war diary, 1914-1918, London 1933: I. Nicholson & Watson.

- Sanders, Michael / Taylor, Philip M.: British propaganda during the First World War, 1914-18, London 1982: Macmillan.

- Thompson, J. Lee: Politicians, the press and propaganda. Lord Northcliffe and the Great War, 1914-1919, Kent, Ohio 1999: Kent State University Press.