Introduction↑

Most textbooks agree that the imperialist tensions in the two decades before 1914 contributed to the diplomatic constellation of the July Crisis. However, the extent to which European imperialism was responsible for the outbreak of World War I is both an open and a controversial question. In broaching this issue, this article aims not to give an overview of the history of imperialism and colonialism, but rather to focus on the aspects that might have worsened the relations between the Great Powers and have led to the Great War. The article distinguishes between several levels of analysis. The first part deals with European imperialist cultures and attitudes before the First World War; the second part takes a deeper look at economic and financial imperialism, focusing on Anglo-German relations, which were crucial in the pre-war era; and the third part analyzes the diplomacy of the European Great Powers with reference to imperialist concepts and ideas.

Imperialist Cultures and Attitudes↑

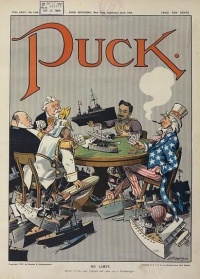

European expansion started in the early modern period, but most historians agree that at the end of the 19th century new forms of imperialism appeared. Between the early 1880s and 1914 the map of the world was redrawn, especially in Africa. With the founding of Germany and Italy, two rather aggressive and aspiring new powers appeared on the scene. After the turn of the century, two non-European states – Japan and the United States – also became imperial powers. Japan successfully fought against China (1894/95) and Russia (1904/05). As a regional Great Power, Japan established colonies in Korea and in the Pacific Ocean. After its victory in the Spanish-American War, the United States conquered a colonial empire of its own in East Asia (the Philippines), occupied Hawaii, and established an informal zone of influence in the Caribbean. The enormous progress in communications (railways, trans-oceanic telegraph lines, steamships), the second industrial revolution (steel, electricity, energy, chemistry), and technical progress in weapon technologies (modern artillery, Maxim-guns or machine guns) had enabled Europeans and North Americans to occupy and control territories and states which were either unknown (the African interior) or even perceived to be culturally superior (like China) some decades before the First World War. The reasons for the acceleration of European expansion in the second half of the 19th century are still subjects of controversial debates, but this topic calls for a separate analysis.[1]

The technical progress after the 1870s led to the appearance of new attitudes in several European countries, while important social groups demanded more aggressive expansion outside of Europe. With the exception of the Russians, ruling liberal and conservative elites were increasingly influenced by vague forms of Social Darwinism. Many statesmen before 1914 were convinced that the concept of the struggle for existence was also valid in foreign policy. Empires and nation states were seen as entities that could rise and fall. According to the principle of Social Darwinism, only the strongest states would survive. Colonial expansion was therefore viewed as a precondition for gaining access to necessary resources. This imperialist mood was directly influenced by the idea of the “survival of the fittest”. Contemporary Social Darwinism was explained in a nutshell by the conservative British Prime Minister Lord Robert A. Salisbury (1830-1903) in a famous speech in 1898: “You can roughly divide the nations of the world in the living and the dying.”[2] In his famous inaugural lecture in Freiburg, the German sociologist Max Weber (1864-1920) said that the founding of the German Empire in 1871 would have been only a prank if it did not lead to further colonial expansion and to German participation in world politics.[3]

This belief in the survival of the fittest in the field of international relations was not necessarily racist, since according to this view the struggle for existence was valid for the competition among the “white” European nations as well. However, the concept often had racist overtones, especially if non-white or non-European civilizations were competing with the European imperial powers. This fact might explain the popularity of the concept: imperialists and nationalists from rather different political camps could agree on the need for expansion. In most of the imperial powers (Britain, France, Germany, and Italy), elites with different backgrounds were convinced that only expanding countries with colonies or informal spheres of influence would be able to survive in the future. It was taken for granted that hierarchies of civilizations existed, with the industrialized European countries and the United States at the top. The only non-white exception was Japan, which managed to become a “civilized” and militarized state due to the Meiji Reform after 1868. Despite the competition between the powers, in major conflicts Europeans could still count on “white” solidarity. In 1900 during the Boxer Rebellion in China all imperial competition was suspended. Faced with an extra-European enemy the imperial powers united in an unprecedented fashion and dispatched an army that suppressed the rebellion.

The Social Darwinist cultures of imperialism were rooted in different national and social traditions. Pro-colonial movements used a variety of arguments to promote national expansion. Colonies were regarded as necessary because they offered access to raw materials and could serve as outlets for domestic industries, arguments that were used especially in times of economic crises. Other motivations for expanding overseas-empires were based on more traditional forms of nationalism: colonies were seen as objects of national prestige. Especially in the Italian and German cases, historians have debated the significance of social imperialism, the idea that imperial expansion served as a means to calm domestic and social problems and to unify the nation. Even if this was not the only reason for German imperialism and colonialism, Chancellor Bernhard von Bülow (1849-1929) successfully used social imperialist arguments to integrate the Liberals and the Catholic Center Party into the authoritarian German state at the turn of the century. Before the 1870s the British Empire was mainly based on trade. British economic elites had developed an outlook that has been described as gentlemanly capitalism.[4] However, after the Great Mutiny in India, growing criticism arose among the British public. It was the conservative Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli (1804-1881) who successfully embraced social imperialist arguments. In his famous speech in the Crystal Palace on 24 June 1872, Disraeli celebrated the British Empire as a source of prestige and defended it against critics. He accused the Liberals of undermining the empire by thinking purely in financial and material terms and by forgetting about issues such as greatness, pride, and respect for the world.[5]

In many cases, Christian missionaries also supported imperialist ideas and colonial expansion. In general the missionaries were Janus-faced. On the one hand, they preached the gospel and tried to protect the indigenous populations from cruelties committed by colonial authorities and conquerors. Many scandals about the suppression, mistreatment or massacre of native populations in the colonies became publicized in Europe because missionaries used their contacts in the press and with individual members of parliaments. On the other hand, missions and missionaries often welcomed colonial occupation, since the protection by colonial military authorities was the only way to reach unknown and often dangerous regions in the African interior, such as the Congo.[6]

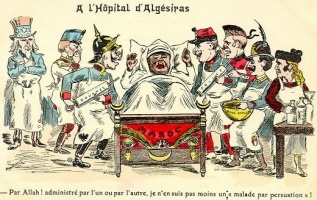

European expansion was often justified by the idea of the so-called “civilizing mission”. In some cases this was purely cynical colonial propaganda, but this concept also served as a powerful ideological framework to proclaim not only European technical and military superiority, but also cultural superiority. In France, the “mission civilisatrice” became the official colonial ideology of the Third Republic after 1871. In Germany this term was not used, but instead Germans spoke about “cultural work overseas”. In Anglo-Saxon countries the idea of the civilizing mission was extremely popular, epitomized in Rudyard Kipling’s (1865-1936) famous poem about the “white man’s burden”. It was the destiny of the white races to lift up mankind and to bring the lights of civilization even to the darkest places of the world.[7]

Public opinion created a pro-imperialist mood that contributed to the worsening of relations among the Great Powers before 1914. Strong and effective colonial pressure groups pushed for colonial and informal imperialist expansion. Some examples show how governments, both those democratically elected and not, lost any room for diplomatic maneuvering because of public opposition to certain beliefs. The important role of pro-colonial pressure groups can already be seen in the Heligoland-Zanzibar Treaty of 1890. From the German perspective, this Anglo-German agreement was a success; Germany acquired the island of Heligoland, which was of enormous strategic importance, in exchange for the African island of Zanzibar, which it hardly controlled. However, this treaty caused public protest in Germany and led to the foundation of the Pan-German League (Alldeutscher Verband), which later became a small but very influential pro-colonial and hyper-nationalist pressure group. The Pan-Germans played both a destructive and a decisive role in domestic politics. Many members came from the intellectual bourgeoisie and from right wing liberal elites: many professors, teachers, intellectuals and journalists joined the league or sympathized with it. After the turn of the century the Pan-Germans took over anti-Semitic and hyper-nationalist arguments and became a kind of intellectual clearing center for racist, imperialist, and nationalist ideas.[8]

Today, historians agree that the famous Kruger telegram, sent by Wilhelm II, German Emperor (1859-1941) to the president of the Republic of South Africa after the failure of the British Jameson raid in 1895, was a severe diplomatic mistake. The German emperor surrendered his neutrality and symbolically joined the Boers against British South Africa when it was not necessary. However, the German public welcomed this step. During the Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902), British journalists and the jingoistic press, later classified as “scaremongers”,[9] created not only an aggressive anti-Boer mood in Britain, but also attacked both the German government and the German people because of their alleged support for the Boer Republics. Likewise, several strong anti-British propaganda campaigns created popular support for the freedom-fight of the Boers among the German public, using anti-British propaganda and comparing the struggle to that between David and Goliath. At the same time, neither the German nor the British government was interested in worsening bilateral diplomatic relations because of the Boer question. However, both governments were facing enormous difficulties trying to calm the press in their respective countries.

Comparable problems appeared repeatedly in the decade before 1914. The plan for Anglo-German cooperation on the Baghdad Railway failed in 1903 because the nationalist British press initiated a vigorous campaign against the idea that British bankers and British money should participate in a “German” imperial enterprise. Although the British government favored a compromise solution, British support for the railway in the Ottoman Empire became impossible due to the public outcry against it. Arguments against British participation were soon adopted by several members of Parliament. Imperialist “men on the spot” in China tried to influence the British press as well. Dr. George Ernest Morrison (1862-1920), correspondent of The Times in Beijing, initiated anti-German press campaigns and even demanded a preventive war against Germany in 1909 because of informal German imperialism in China. He was convinced that a major European war with Germany as a main aggressor was bound to occur, no matter what the British government did to appease Berlin. In Italy, beginning in the 1890s public opinion also contributed to the creation of a pro-imperialist and expansionist mood. The Liberal Party had thus far been unable to form a homogenous nation state, although the unification of the country had already started in the 1860s. The creation of an Italian empire in Africa seemed to be a means both of distracting critics at home from discussing domestic problems and of creating a unifying feeling. However, this failed when the Italian colonial army suffered a disastrous and humiliating defeat by the independent state of Ethiopia in 1896. The hope for revenge for the “shame” of Adowa, combined with the Liberals’ inability to find solutions for the lasting differences between Italy’s northern and southern regions (the “risorgimento”) contributed to its aggressive foreign policy in 1911 and to its military attack on Libya, until then formally a part of the Ottoman Empire.

Economic and Financial Imperialism↑

According to Paul Kennedy, economic imperialism and the Anglo-German trade rivalry were crucial factors leading to the emergence of the Anglo-German antagonism, which contributed to the outbreak of World War I.[10] By the end of the Bismarck era, high German tariffs and growing protectionism had already excluded many British goods from the German market. However, despite Kennedy’s precise analysis of trade, this thesis is based on an oversimplification of complex relations. One has to distinguish between the objective figures on the one hand and the perceived situation on the other. In relative terms, in the two decades before 1914 one can talk about a British decline and a German rise in export economies. In 1910 Germany’s share of the world’s manufacturing capacity was already greater than that of the British. For British Social Darwinists and nationalists, this development was identical to decline. However, this view did not capture the reality of economic developments. Germany remained an important market for British goods and vice versa. In 1913 Germany was in fact the second biggest market for British exports and re-exports. Even if trade rivalry was a problem for individual firms, its dramatization was mainly due to the press, which explained Britain’s relative decline with notions such as “unfair competition”. Especially in imperial affairs, German and British traders and bankers often cooperated quite successfully; at the same time, German banks had to compete with other German firms, while British banks had to deal with British competition.

Unlike the British or French colonies, economically the German colonial empire was not important for the mother country. It was also of little significance for the rising tensions between the European Great Powers prior to the First World War. For the overseas expansion of European states in the decades before 1914, informal imperialism and indirect rule were often much more important than formal colonialism, as discussed during the famous Robinson/Gallagher controversy.[11] The economic expansion of European firms, banks and merchants, sometimes openly supported by “their” respective governments, created spheres of influence that could later became areas of international and imperialist competition. However, even if states and governments tried to control this form of economic expansion and hoped to use it in connection with “national” political aims, economic and financial imperialism very often remained a multinational project. It would be wrong to assume that “British”, “French” or “German” enterprises always acted in the interests of their governments. In Neo-Rankean terminology, used both by contemporary diplomats and by diplomatic historians, states acted as subjects and consequently the economy was nationalized. However, economic imperialism followed its own rules, which in some cases fit with the respective national political interests but did not necessarily have to.

The intricate diplomatic and political problems caused by economic expansion are illustrated by the example of the famous Baghdad Railway project. Since the late 1880s German banks, especially the Deutsche Bank, had been active in Turkish affairs and in financing several Turkish railway enterprises. At the turn of the century the position of German firms was so strong that one can refer to certain regions of Turkey as parts of a German economic informal empire. The government of the Ottoman Empire tried to persuade the German bankers to extend the already existing railway lines to Baghdad and the Persian Gulf, mainly for strategic reasons. However, as mentioned above, in 1903 these ideas met with British resistance, as this line would have been the fastest route to India and would have been controlled by German firms. At the same time, the German public discovered the project and started to “nationalize” it. However, despite the fact that both German public opinion and the German government favored this “German” railway line, it remained a multinational enterprise: more than one-third of the capital came from French investors and French bankers, although the French government openly opposed the project. Before 1914 financial imperialism very often remained multinational despite governmental attempts to nationalize it. Banks viewed these projects as commercial opportunities and were unconcerned with national prestige. Many governments were not even informed about the activities of “their” banks, although in general they were aware that many firms did not follow the respective “national” aims, but were mainly interested in earning money.[12]

If one compares political with economic/financial imperialism, one other general distinction should be made. Governments acted within the frame of the nation state or empire and often tried to further national expansion. Multinational firms and banks, however, were confronted with the challenge of economic globalization and had to act internationally if they wanted to expand overseas. Until 1914 London remained the financial clearing center of the world and the London stock exchange was the most important place for all kinds of transactions. The gold standard guaranteed stable exchange rates, and internationally the pound sterling was the most accepted currency for bills of exchange. In private a banker or trader could have been a hardcore nationalist, but if he wanted to earn money he had to act internationally. Not only in India, but also in many other regions of the world such as China, South Africa, Egypt, and some Latin American countries, merchant bankers and traders from various countries were able to invest and earn money because the British Empire and the British navy directly and indirectly guaranteed stable relations and preserved so-called “Western” liberal norms and laws.

In a couple of cases economic investments could spur imperial conflicts. Governments could claim to protect or defend investments that were threatened by an indigenous state or an imperial competitor. Examples include the bankruptcies of Egypt (1876) and the Ottoman Empire (1875) and the Venezuelan debt crisis, which started at the end of the 19th century. After the breakdown of state finances in Egypt and Turkey, private committees of bankers founded new institutions (Caisse de la Dette Publique Égyptienne, Caisse de la Dette Publique Ottomane), which took control of tax revenues. As a result, the states lost a considerable part of their sovereignty and foreign banks controlled the state’s budget. For European firms this classical form of financial imperialism was much more effective than direct rule. At the same time, behind the scenes European governments tried to influence “their” committees and bankers. During the 1870s and 1880s in Egypt, several disputes between the French and the British caused tensions. For the British, the German support was crucial. The Venezuelan debt crisis of 1902/03 led to serious tensions between some European states, notably Germany and the United States. After internal uprisings and civil war, the Venezuelan government was unable to pay back its foreign debts. A British-German-Italian naval blockade escalated as German cruisers provoked skirmishes. These military events alarmed the United States, which feared that the Monroe Doctrine would be violated.

However, even if informal and financial imperialism contributed to the worsening of relations between certain states during this first wave of globalization between the 1880s and 1914, during this period close economic ties and global financial networks were also created.[13] Because of the combination of cooperation and competition among multinational firms, some contemporary commentators believed that a major war in Europe was impossible, arguing that economic globalization would guarantee peace. They were convinced that countries would not risk destroying the global economic system. They strongly believed that the destruction of the close connections in finance and trade, which would be the result of a great war among the European powers, would lead to a global economic disaster. As World War I showed, this opinion was correct.

Between 1912 and 1914 the British government tried to improve Anglo-German relations through economic imperialism. It is possible that the British attempted to appease Germany’s aggressive imperialism by offering it colonial acquisitions in Africa. After the failure of the famous Haldane Mission in 1912, British statesmen looked for objectives outside of Europe for which there could be compromise solutions with Germany. The extremely difficult negotiations for the Baghdad Railway were successfully finished in the spring of 1914. Additionally, in the 1913 treaty partitioning the Portuguese colonies, the British accepted huge German colonial acquisitions in Africa at the expense its traditional ally, Portugal. In the same year German banks and firms created economic zones of interest (using railway projects and chartered companies) in southern Angola and in the north of Mozambique. By the summer of 1914, economically the two regions were firmly in the hands of the Germans and could have been annexed under the pretext of a violation of German interests by Portuguese authorities. This example shows that both Africa and smaller European states like Portugal were simply pawns for the European Great Powers. At the same time, economic imperialism could be used as a means to defuse political tensions.

Even if in some cases a strong British-German trade rivalry existed, the reaction of leading bankers and economists interested in imperial projects showed that they were not interested in going to war with one another. Karl Helfferich (1872–1924) was one of the most nationalist German bankers and as a director of the Deutsche Bank was responsible for the Baghdad Railway. When he heard the news of the British declaration of war in August 1914 he reacted with dismay: “...the result will be an expanse of rubble”.[14] Charles Addis (1861-1945), the head of the Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation, which often cooperated with German firms in China, showed no enthusiasm for war either. After a conversation with Sir Edward Grey (1862-1933), the British Foreign Secretary, he wrote: “Yes, we had to fight, but what a hateful necessity. I suppose Germany, our best customer, will be beaten. And what then?[15]

Imperialism, diplomacy, and the “Concert of Europe”↑

The third part of this article deals with diplomacy and imperialism. Both contemporaries and historians of diplomatic relations have used the term, the “Concert of Europe”. This term remains popular but is misleading. The European orchestra played without a conductor and without clearly accepted rules of international law. If there was anything like a system it was organized and held together by the governments of the Great Powers, which followed their own interests and jealously prevented other states from becoming too strong or reaching a hegemonic position. Since the end of the Napoleonic Wars, disputes over colonial or imperial issues had not escalated to the point where peace in Europe was threatened. This was in large part because conflicts did not touch on interests that the European powers regarded as vital. A few exceptions, such as the Fashoda Crisis of 1898, which nearly led to war between France and Britain, and the Second Moroccan Crisis, which will be discussed later, prove the rule. However, disputes at the so-called periphery could strongly influence the competition between the Great Powers in Europe and could lead them to redefine their interests in Europe.

The reasons for the acceleration of European expansion during the 1880s are still being debated, but this article concentrates on the diplomatic processes and consequences of imperial expansion. Christopher Bayly has touched upon the dimensions of the “new imperialism”.[16] Encouraged by influential regional pressure groups in 1881, France occupied Tunis. This surprising step led to serious tensions with Italy, which was also interested in this territory. The French annexation had direct repercussions for the European system; fearing further French aggressions, the Italian government joined the German-Austrian-Hungarian military defensive alliance. In the next year, following nationalist uprisings, the British navy attacked Alexandria. The Suez Canal was the shortest route between Europe and India, and the British government regarded control as vital. Although Egypt formally remained a part of the Ottoman Empire, the British consul-general Evelyn Baring, Earl of Cromer (1841-1917) exercised the real power and British officials occupied key positions in the government. The scramble for Africa reached its climax when in 1884/85 Germany surprisingly acquired several colonies in Africa. From today’s perspective, it is remarkable that despite the fast expansion, the ongoing tensions, and the constant competition between the powers no bellicose mood arose among the European states. Nearly all the Great Powers (with the exception of Austria-Hungary and Russia) and even one smaller European country (Belgium), were interested in acquiring territories in Africa. However, their governments quickly recognized that the scramble for Africa could have undesired diplomatic repercussions in Europe.

Otto von Bismarck’s (1815-1898) maxim was to keep good diplomatic relations with Britain, as good Anglo-German relations were central for maintaining peace in Europe. Indeed, before the turn of the century no imperialist crisis occurred that led to serious or lasting tensions between London and Berlin. By 1877 (Kissinger Diktat) Bismarck had formulated the basic ideas for his foreign policy. He believed it was necessary to promote and support the aggressive tendencies among the European Great Powers, but that these tendencies should be directed towards the periphery. Consequently, at the beginning of the 1880s German diplomats encouraged the French government to expand in Africa, hoping for conflicts between the French, Italians, and British. Several times Bismarck promoted Russian or British expansion, knowing that Germany’s neutrality would bring certain advantages as long as it did not act aggressively on the imperialist stage.

In 1885 the West Africa Conference took place in Berlin. Its aim was to keep conflicts arising from the scramble for Africa under the control of the Great Powers. During this conference the participants set up certain rules for future expansion.[17] The consequences for the indigenous Africans were ignored; at the beginning of the meeting only the British ambassador briefly mentioned a special European responsibility. Africa was declared to be “terra nullius”, i.e. the Europeans agreed that African rule did not exist in the sense that European sovereignty did. The concept of effective control was introduced. This meant that it was no longer enough simply to plant a flag somewhere in the African soil; rather, visible institutions such as police stations, trading posts, or missions had to be established. The result was an enormous acceleration of European colonial expansion and sub-imperialism. Even territories that were of no use for European states were quickly occupied because of the fear that they would be taken by another country. The Congo Basin became a zone of free trade under the protection of Leopold II, King of the Belgians (1835-1909), who established one of the most brutal and repressive colonial regimes ever seen in Africa.

When Leo von Caprivi (1831-1899) became Chancellor in 1890, the Berlin government returned to a strictly anti-imperialist policy. A precise and concise analysis of German trade relations and capital investments worldwide showed that Germany was already an export-oriented nation and that German strength would grow even if exports were promoted by an active foreign policy. Consequently, Caprivi initiated a policy of free trade. Treaties including the most-favored-nation clause were signed with a growing number of countries.[18] In a major conflict it would have been easy for the British navy to cut off Germany’s ties to the non-European world. Caprivi again found a simple solution: Germany’s security was guaranteed as long as the Anglo-German relations remained good and the German army was able to deter any continental competitor. Consequently, Caprivi was not interested in imperial expansion or in the acquisition of colonies, which would only create problems. Until 1894 the orientation of German foreign policy remained strictly continental.

After the fall of Caprivi in 1894, German politics slowly changed towards an active imperialist policy, characterized by the terms navalism and “world politics” (“Weltpolitik”). During several cabinet reshuffles, more and more politicians who favored an expansionist policy reached leading positions in the state bureaucracy. Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz (1849-1930) proclaimed that a strong battle fleet was to be built. Like Admiral Alfred Thayer Mahan (1840-1914) in the USA and the Jeune École (Young School) in France, Tirpitz used a variety of arguments to convince both parliament and the public that a navy was necessary to avoid decline. This huge and successful propaganda campaign for a battle fleet had a number of consequences: historians were paid to publish on maritime power in history; the sailors’ dress became popular among schoolboys; and a career in the navy became attractive for young men with a bourgeois background who had difficulties reaching higher officer ranks in the still aristocratically dominated army. The ministry also indirectly promoted the Navy League (“Flottenverein”), which became one of the strongest internal pressure groups in the following years. Emperor Wilhelm II, who had been a naval enthusiast since his youth, openly supported Tirpitz as well, and a powerful military-industrial complex (Krupp) grew from the armament programs.

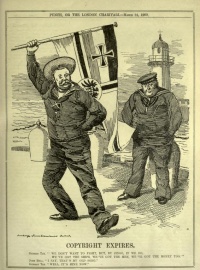

The Anglo-German naval race became one crucial factor on the twisted road to World War I. The German battle fleet was unable to defend German overseas interests, having been built only to stop Great Britain. The strategic idea behind this navy has been described by the term “risk fleet”, i.e. the fleet should be able to deter Britain from attacking Germany. The German admirals were aware of the fact that a full victory in a naval battle would be impossible, but as an Anglo-German war would be too risky for Britain, she would be forced to maintain good relations with Germany and to grant colonial compensations. The navy was thus built to put pressure on Great Britain. Rolf Hobson analyzed Germany’s main strategic mistake in detail, arguing that the battle fleet was built for a great naval battle, but was unable to force England to fight such a battle and was useless against a blockade.[19] It also did not deter Britain, but instead set in motion an arms race that worsened Anglo-German relations. It also forced the British government to reduce colonial rivalries elsewhere, for example by settling differences with France. This in turn led to more cordial relations between the two countries and paved the way for the future Entente Cordiale.

In 1897 in connection with the decision to build a battle fleet, the new chancellor Bernhard von Bülow gave a famous speech, demanding a “place in the sun” for Germany. Bülow had been inspired by social imperialism, as evidenced in his ideas about foreign policy. He demanded expansion with the aim of uniting and reconciling the German people and minimizing social conflicts at home. It was therefore less important in which part of the world colonies were acquired; rather, expansion became an end in itself. A contemporary observer, Joseph Schumpeter (1883-1950), described this policy as imperialism without objects. Beginning in the late 1890s, Germany’s foreign policy became more and more aggressive, as is visible in the German annexation of Kiautschou in China. Although Germany had few economic and political interests in the Far East, after the Chinese defeat in the Sino-Japanese War Germany joined the Russian and French side in protesting the Treaty of Shimonoseki. The protests, however, had almost no effect but was welcomed by much of the German public, as it was now clear that Germany could act as a veto-power in East Asian affairs. However, the victorious Japanese were facing a new and unexpected rival and the Chinese government saw no reason to be grateful to Germany and grant a German naval base in return. In 1897 German diplomacy used the murder of two German missionaries as a pretext to annex the important harbor of Kiautschou. In the following years the province of Shandong in northern China became a German zone of economic and political interest. Germany, France, and Britain openly promoted banks and firms during the so-called scramble for China. Although all European banks welcomed the diplomatic support of their respective governments, they cooperated closely if the Chinese threatened any of their interests.

The growing imperialist tensions at the turn of the century forced the British government to minimize some of its conflicts at the periphery. In the wake of Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone’s (1809-1898) time in office, British liberals were aware of the danger of overstretching the British military and economic power in imperial affairs. The first Anglo-Japanese Alliance, signed in 1902, was the only British military alliance before the First World War. This alliance signaled a far-reaching step in international and imperial diplomacy. Britain accepted the young Japanese state as a junior partner; at the same time, the British navy diminished its presence in the Far East. Once the scramble for China ended, this alliance was directed against Russia and its ambitions in China and Korea. It was also used to challenge German aspirations in the region. Furthermore, it gave Japan a free hand to prepare for war against Russia, which came two years later. For the first time a clear diplomatic constellation existed, one that the British used several times. When tensions between the European powers over extra-European affairs endangered British interests, the British government reached regional compromises in order to concentrate on more important matters. In 1902 Russia, not Germany, was still the main threat for Britain. However, as a result of more aggressive German foreign policy this began to change.

Surprisingly, in 1904 Britain and France reconciled and signed the Entente Cordiale. This treaty was an indirect effect of the Fashoda Crisis and was not a military alliance. However, all open colonial disputes were settled with the treaty. Following the conclusion of the entente agreement, no further imperial tensions occurred between the two states. German attempts to test how firm this new Anglo-French partnership was failed during the First Moroccan Crisis in 1905/06. In 1907, in a famous memorandum, Eyre A. Crowe (1864-1925), a senior diplomat in the British Foreign Office, concluded that not Russia but Germany was the most dangerous competitor for Great Britain. He strongly urged an anti-German policy, arguing that concessions would only increase Germany’s appetite. Consequently, the British tried to minimize existing imperial tensions with Russia. On the face of it, the Anglo-Russian Entente of 1907 was an agreement relating only to Persia; Persia was divided into a British, a Russian, and a neutral zone of interest. In reality, this treaty ended all imperial tensions between the two countries, allowing the British to focus on the German danger.

The Austro-Italian antagonism led to other imperial conflicts that overshadowed the harmony of the so-called Concert of Europe before 1914. During the Bismarck years, Italy had joined the German-Austrian military alliance, as it had been looking for diplomatic support against aggressive French imperialism after the annexation of Tunis in 1881/82. However, during the following decades Franco-Italian relations improved while tensions with Austria grew, especially in the Balkans. In Italy the Balkans were seen as a possible field of future expansion, while most politicians in Vienna regarded this region as the natural backyard of the Habsburg Empire. Tensions in the Balkans, such as the Austrian annexation of Bosnia in 1908, seriously threatened the relationship between Austria-Hungary and Italy. Although both countries were members of the same military alliance, they built systems of fortresses against each other at the Austro-Italian border and initiated an arms race.[20]

The Second Moroccan Crisis, which reached its climax in September 1911, was a watershed event. When Alfred von Kiderlen-Wächter (1852-1912), the German Secretary of Foreign Affairs, decided to send the gun-boat Panther to the Moroccan harbor of Agadir, he escalated a situation he could not control. Even though the French had violated some articles of the Algeciras Treaty of 1906, which had regulated the status of Morocco, most of the European governments regarded the German step as an overreaction not justified by German interests in the region. As the French government could count both on Russian and British support, it saw no reason to retreat. Both sides escalated the conflict until in September 1911 Europe was on the brink of war.

To make matters worse, public opinion in both countries left little room for diplomatic maneuvering. In France, the German gunboat was seen as a direct attack on the French semi-colony Morocco. The nationalist press mobilized the public to stand firm against German imperialist demands. In Germany, the situation was similar: to gain the support of the press, Kiderlen-Wächter had informally requested that Heinrich Class (1868-1953), head of the Pan-German League, start a powerful propaganda campaign. Consequently, the nationalist press initiated a public outcry in favor of annexing West Morocco. However, this strategy failed. The government had little trouble setting the nationalist outcry in motion, but rather more trouble stopping it.

After contentious negotiations, a compromise was found. France received the right to establish a full colonial regime in Morocco. As compensation it handed over territories in central Africa that it barely controlled. For the French nationalists the concessions were too much, while for their German counterparts they were much too little. The Second Moroccan Crisis was the last large imperial conflict among European states before the outbreak of the First World War. Germany acted as the main aggressor. The diplomatic constellation of the July Crisis had already become visible. Although neither the Entente Cordiale nor the Anglo-Russian Entente contained any military regulations and Great Britain did not join any European military alliance before August 1914, at the climax of the crisis British and French talks started between the army leadership. Over the following years the informal military cooperation intensified.

The imperialist policy in the Balkans contributed significantly to the July Crisis. Between 1908 and 1914, the region was in permanent turmoil. As a result of the two Young Turk Revolutions in 1908/09, in several of the Balkan states hyper-nationalist movements gained considerable support among both radical intellectuals and the broader population. Nation-building at the expense of the Ottoman Empire went hand in hand with processes of decolonization. Moreover, to a growing extent ethnic cleansing became a weapon used against civilians. However, in these multilingual and multi-religious regions it was impossible to define territorial borders according to nationalities. Multi-ethnic identities were normal, while “pure” ethnicity was the rare exception.[21]

In October 1908, the Austrian-Hungarian government annexed Bosnia, which was formally a part of the Ottoman Empire. This new territory became a “protectorate” and was administered by the Austrian Ministry of Finance. In 1912 a newly formed coalition of Balkan states started a war of aggression against the Ottoman Empire. Within a couple of weeks the Turkish army collapsed. Some of the Great Powers were drawn into the struggle against their wishes and were forced to define their interests. In Austria-Hungary and Germany the fear of the Russian pan-Slavic movement was widespread. On several occasions, leading officers of the Central Powers demanded a preemptive war. However, even if some Russian intellectuals and young officers supported a pan-Slavic ideology, it hardly influenced the decisions of the Russian government. It was in Russia’s interest to defend Serbian independence against Austrian-Hungarian colonial ambitions. The two Balkan Wars were settled by conferences in London attended by the Great Power’s ambassadors. However, in 1914 the situation in the Balkans was still dangerous, as the Great Powers were unable to control the strong revisionist and nationalist tendencies. Especially in Austria-Hungary, influential politicians and the general staff were pushing for a great war in order to realize far-reaching imperial ambitions. Unlike other imperial powers, who saw war as a threat to the integrity of their imperial domains, the Young Turks regarded war as a chance for national and imperial renewal.

Conclusion↑

Even if imperialism was one of the crucial factors that led to World War I, it is striking that by early 1914 all colonial disputes between Germany and Britain had been solved. After long and difficult debates and diplomatic maneuvers, the agreements concerning the Baghdad Railway had resulted in compromise solutions in which all parties (except the Ottoman Empire) profited. British diplomacy stopped resisting the German-Turkish project of building a railway from Constantinople to the Persian Gulf. However, the Germans agreed that the last section of the line would be built only by British investors and would be under sole British political and economic control. A compromise was also found in the question of the Mesopotamian oil fields. The secret Anglo-German treaty of 1913 concerning the partition of the Portuguese colonies was a German success as well. Britain agreed to act against the political interests of its traditional ally, Portugal, and used the question of the colonies to appease Germany. By 1912/1913 the extra-European world had been stabilized. From this perspective, World War I began as a European war but then had global and imperial consequences because of the nature of the states that took part in it.

Imperialism was responsible for reforming the European alliances.

- Imperialist expansion played a major role in the growing tensions between Germany and Great Britain after the turn of the century. The growing imperialist rivalry was responsible for the slow formation of an anti-German alliance system in Europe. Because of the increasing imperial competition and the naval race, the British decided to work with France and to sign the Entente Cordiale in 1904, thus putting an end to long-standing Franco-British colonial rivalries.

- German diplomacy was based on the conviction that the Anglo-Russian antagonism would remain a central factor for Great Power diplomacy no matter how Germany acted. However, the same constellation that led to the Franco-British détente also forced Britain to change its policy towards Russia. In 1907 Eyre Crowe formulated his famous memorandum predicting that Germany, not Russia, would become the most dangerous threat for Britain. In the same year the Anglo-Russian treaty on the partition of Persia was signed, ending any major imperial rivalry between the two countries. Neither of these treaties was a military alliance, but they shaped British foreign policy, as the British continued to view Germany as the only dangerous international competitor.

- Between 1911 and 1913 the British concluded that relations with the aggressive Wilhelmine state had to be improved to avoid the danger of a major European war. After the failure of the famous Haldane Mission, British statesmen looked for initiatives in imperial affairs for which compromise solutions with Germany could be found. The difficult negotiations for the Baghdad Railway were successfully finished in the spring of 1914. Additionally, with the 1913 treaty partitioning the Portuguese colonies, the British allowed Germany to acquire territory in Africa at the cost of its traditional ally Portugal. As a result, by the summer of 1914 the period of Anglo-German imperial rivalry had ended.

- By the end of the Second Moroccan Crisis most of the colonial disputes between Berlin and Paris had also disappeared. The French colonial administration focused on penetrating and stabilizing its newly acquired African territories. In the Balkans, however, the combination of conflicting Austro-Hungarian, Italian, and Russian imperialist aspirations, the breakdown of the European region of the Ottoman Empire, and aggressive processes of nation building (in Greece, Bulgaria, Serbia, Romania) had been an increasing threat since 1912. Ultimately, the explosive combination of these events contributed to the constellation of the July Crisis in 1914.

Boris Barth, Universität Konstanz

Section Editors: Annika Mombauer; William Mulligan

Notes

- ↑ See: Mommsen, Wolfgang J.: Theories of Imperialism, Chicago 1982.

- ↑ The “dying nation” speech was first published in The Times 5 May 1899.

- ↑ Inaugural lecture, in: Weber, Max: Gesammelte Politische Schriften, Tübingen 1968, pp. 21-23.

- ↑ For the “Gentlemanly Capitalism” theory see: Cain, Peter / Hopkins, Anthony: British Imperialism, London 2001.

- ↑ Speech at the Banquet of the National Union of Conservative and Constitutional Associations at the Crystal Palace, on 24 June 1872, in: Helmut Viebrock (ed.): Disraeli, Wiesbaden 1968, pp. 12-15.

- ↑ For the British case see: Porter, Andrew: Religion versus Empire? British Protestant Missionaries and Overseas Expansion, 1700-1914, Manchester 2004.

- ↑ See: Barth, Boris / Osterhammel, Jürgen (ed.): Zivilisierungsmissionen. Imperiale Weltverbesserung seit dem 18. Jahrhundert, Konstanz 2005.

- ↑ For the Pan-Germans, see: Chickering, Roger: We Men Who Feel Most German. A Cultural Study of the Pan-German League, 1886-1914, Boston 1984.

- ↑ See: Morris, Andrew J.: The Scaremongers. The Advocacy of War and Rearmament 1896-1914, London 1984.

- ↑ See: Kennedy, Paul: The Rise of the Anglo-German Antagonism 1860-1914, London 1982.

- ↑ See: Robinson, Ronald / Gallagher, John: The Imperialism of Free Trade, in: Economic History Review 6, 1953, pp. 1-15; Louis, W. M. Roger: Imperialism. The Robinson and Gallagher Controversy, New York 1976.

- ↑ See: Barth, Boris: Die deutsche Hochfinanz und die Imperialismen. Banken und Außenpolitik vor 1914, Stuttgart 1995.

- ↑ Osterhammel, Jürgen / Petersson, Niels: Globalization. A Short History, Princeton 2005.

- ↑ Quoted in: Seidenzahl, Fritz: 100 Jahre Deutsche Bank. 1870-1970, Frankfurt am Main 1970, p. 252.

- ↑ Quoted in: Dayer, Roberta A.: Finance and Empire. Sir Charles Addis, 1861-1945, London 1988, p. 79.

- ↑ See: Bayly, Christopher: The Birth of the Modern World 1780-1914, Oxford 2004, pp. 228-233.

- ↑ See: Förster, Stig et al. (ed.): Bismarck, Europe, and Africa. The Berlin Africa Conference and the Onset of Partition, Oxford 1988.

- ↑ For Caprivi’s policy of free trade see: Weitowitz, Rolf: Deutsche Politik und Handelspolitik unter Reichskanzler Leo v. Caprivi, Düsseldorf 1978.

- ↑ Hobson, Rolf: Imperialism at Sea. Naval Strategic Thought, the Ideology of Sea Power, and the Tirpitz Plan, 1875-1914, Boston 2002.

- ↑ See: Afflerbach, Holger: Der Dreibund. Europäische Großmacht- und Allianzpolitik vor dem Ersten Weltkrieg, Wien 2002.

- ↑ See for example: Naimark, Norman M.: Fires of Hatred. Ethnic Cleansing in Twentieth-Century Europe, Cambridge, MA 2001.

Selected Bibliography

- Afflerbach, Holger: Der Dreibund. Europäische Grossmacht- und Allianzpolitik vor dem Ersten Weltkrieg, Vienna 2002: Böhlau.

- Barth, Boris: Die deutsche Hochfinanz und die Imperialismen. Banken und Aussenpolitik vor 1914, Stuttgart 1995: Steiner.

- Barth, Boris / Osterhammel, Jürgen (eds.): Zivilisierungsmissionen. Imperiale Weltverbesserung seit dem 18. Jahrhundert, Konstanz 2005: UVK Verlagsgesellschaft.

- Bayly, Christopher A.: The birth of the modern world, 1780-1914. Global connections and comparisons, Malden 2004: Blackwell.

- Bentley, Jerry H.: The Oxford handbook of world history, Oxford; New York 2011: Oxford University Press.

- Cain, Peter J. / Hopkins, Anthony G.: British imperialism (3 ed.), London 2012: Longman.

- Chickering, Roger: We men who feel most German. A cultural study of the Pan-German League, 1886-1914, Boston 1984: Allen & Unwin.

- Förster, Stig / Mommsen, Wolfgang J. / Robinson, Ronald Edward (eds.): Bismarck, Europe, and Africa. The Berlin Africa Conference 1884-1885 and the onset of partition, Oxford; New York 1988: Oxford University Press.

- Gallagher, John / Robinson, Ronald: The imperialism of free trade, in: Economic History Review 6/1, 1953, pp. 1-15.

- Hobson, Rolf: Imperialism at sea. Naval strategic thought, the ideology of sea power, and the Tirpitz Plan, 1875-1914, Boston 2002: Brill Academic Publishers.

- Kennedy, Paul M.: The rise of the Anglo-German antagonism, 1860-1914, London; Boston 1980: Allen & Unwin.

- Louis, William Roger (ed.): Imperialism. The Robinson and Gallagher controversy, New York 1976: New Viewpoints.

- Mommsen, Wolfgang J.: Theories of imperialism, Chicago 1982: The University of Chicago Press.

- Morris, A. J. Anthony: The scaremongers. The advocacy of war and rearmament 1896-1914, London; Boston 1984: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Osterhammel, Jürgen: Colonialism. A theoretical overview, Princeton; Kingston 1997: M. Wiener; Ian Randle Publishers.

- Osterhammel, Jürgen / Petersson, Niels P.: Globalization. A short history, Princeton 2005: Princeton University Press.

- Porter, Andrew N.: The Oxford history of the British Empire. The nineteenth century, volume 3, Oxford 2001: Oxford University Press.

- Porter, Andrew N.: Religion versus empire? British Protestant missionaries and overseas expansion, 1700-1914, Manchester 2004: Manchester University Press.

- Rosenberg, Emily S. / Iriye, Akira / Osterhammel, Jürgen (eds.): A world connecting, 1870-1945, Cambridge 2012: Harvard University Press.

- Wallerstein, Immanuel Maurice: The modern world-system IV - Centrist liberalism triumphant, 1789-1914, Berkeley; London 2011: University of California Press.