Introduction↑

The First World War should be understood in its South East European context as a conflict of varying intensity beginning in 1912 and enduring through 1918. All of the Balkan states became involved in this fighting. During this time, all of the states there achieved victories and all suffered defeat. In the First Balkan War of 1912-1913, a loose alliance between Bulgaria, Greece, Montenegro, and Serbia triumphed over the Ottoman Empire. In the Second Balkan War of 1913, Bulgaria was overwhelmed by its erstwhile allies along with the Ottomans and Romania. None of the Balkan states regarded the peace settlements of Bucharest and Constantinople, which ended the Second Balkan War in August and September 1913 respectively, as permanent. Low-level fighting continued in the former Ottoman ruled regions of Albania, Kosovo, and Macedonia by Albanians and Bulgarians opposed to the new Serbian occupation through the fall of 1913 and the spring of 1914. The conflict openly resumed in southeastern Europe in the summer of 1914. As the fighting continued as the First World War, Greece, Montenegro, Romania, and Serbia came to support the Entente. Only Bulgaria devoted itself to the cause of the Central Powers.

Bulgaria experienced one victory and two defeats during the prolonged war of 1912-1918. To a great degree, the explanation for this situation lies in the problem of Macedonia. 19th century Bulgarians, Greeks, and Serbians all regarded Macedonia as integral to the establishment of their national states. This region, which corresponded roughly to the Ottoman province (vilayet) of Salonika (Bulgarian: Solun; Greek: Thessaloniki; Turkish: Selānik), had a mixed population and a productive economy. At the conclusion of the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-1878, the Treaty of San Stefano of 3 March 1878 established at the behest of the victorious Russians a large Bulgaria that included Macedonia. Bulgarian nationalists regarded Macedonia as a region vital to the unity and development of their people. The objections of other Great Powers and other Balkan states forced a revision of this treaty. The subsequent Treaty of Berlin of 13 July 1878 returned Macedonia to Ottoman rule. Nevertheless, the Bulgarians located the capital of their new state in the western part of the country at Sofia, in the expectation that it would be in the center after the anticipated union with Macedonia. During the final years of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, Macedonia became the arena of intense nationalist rivalries that pitted Bulgarian armed bands against those of the Greeks and Serbians. At the same time, all of these groups struggled against the Ottoman authorities.

Balkan Wars↑

An alliance between Bulgaria and Serbia reached on 13 March 1912 under Russian sponsorship assigned most of Macedonia to Bulgaria and left the northwestern region to Russian arbitration.[1] If the Bulgarians and Serbs could not agree upon the division of northwestern Macedonia, which seemed highly likely, Nicholas II, Emperor of Russia (1868-1918) himself agreed to determine the fate of the territory. During the spring and summer of 1912, Greece and Montenegro adhered to this loose Balkan league. The First Balkan War of 1912-1913 began in October 1912 when Bulgaria, Greece, Montenegro, and Serbia fought against their former ruler, the Ottoman Empire. Victorious Bulgarian troops advanced to the final Ottoman defensive positions outside Constantinople at Chataldzha (Turkish: Çatalca) in November 1912 and took the important Ottoman fortress town of Adrianople (Turkish: Edirne; Bulgarian: Odrin) on 26 March 1913 after a four-month siege.[2] After this impressive feat of arms, the Bulgarian military and political position deteriorated rapidly. Intra-alliance quarrels arose over the disposition of Macedonia. The Treaty of London of 30 May 1913 granted Bulgaria eastern Thrace to a straight line from Enos (Turkish: Enez) on the Aegean Sea to Midia (Turkish: Midye) on the Black Sea. The question of Macedonia remained pending. The Russians made minimal efforts to enforce the provisions of the March 1912 treaty.

Fighting was renewed at the end of June 1913 when Bulgarian forces attacked their erstwhile Greek and Serbian Balkan allies. The Ottomans and Romania soon joined the conflict against Bulgaria in what became known as the Second Balkan War. This combination quickly overwhelmed the Bulgarians. The Treaty of Bucharest of 10 August 1913 confirmed Bulgaria’s defeat and the loss of Macedonia to Greece and Serbia, and the fertile agricultural region of southern Dobrudzha (English: Dobruja; Romanian: Dobrodgea) to Romania.[3] After so much sacrifice, this was very difficult for the Bulgarian government to endure.

Up until 1913, the Bulgarians had looked to Russia as its Great Power patron. Russia shared a similar Orthodox Christian culture and Russian troops had freed Bulgaria in 1878 from five centuries of Ottoman rule. Russia guaranteed the 13 March 1912 Bulgarian-Serbian alliance. This meant, at least to the Sofia government, that Russia guaranteed Macedonia to Bulgaria. The Bulgarian perspective proved to be wishful thinking. The Russians, pursuing their own interests in southeastern Europe, made little effort to resolve the Bulgarian-Serbian dispute over the division of Macedonia. The Bulgarian attack on Ottoman defensive positions at Chataldzha in November 1912 almost brought them into Constantinople. This was undesirable to the Russians and did not improve the Russian attitude towards Bulgaria. During the Second Balkan War, the St. Petersburg government avoided any commitment to Bulgaria. This caused the Russophile government of Stoyan Danev (1858-1949) to collapse.[4] The Treaty of Bucharest that ended the Second Balkan War denied the Bulgarians their main national objective. The new Bulgarian Prime Minister, Vasil Radoslavov (1854-1929), who held the office from 1913 to 1918, later wrote, “At Bucharest we realized clearly that Russia had turned away from us. A word from [Russian diplomat Nikolai] Schebeko would have been enough for us to obtain Macedonia and Kavala. That word was not spoken.”[5] Russia’s failure to defend Bulgaria against the predations of her Balkan allies in 1913 led the Sofia government to seek redress in the camp of the Triple Alliance. By the summer of 1914, the Germans had further solidified their position in Sofia by extending a major loan.[6] Russian attempts to deflect the loan proved fruitless.

The estrangement of Bulgaria from Russia left the St. Petersburg government with only Serbia as a reliable ally in southeastern Europe. This was not lost on the Belgrade government. A failure to help Serbia in the July 1914 crisis meant that Russia could lose its last position in southeastern Europe. Because of its proximity to Constantinople, which was astride the passage from the Black Sea to the Mediterranean and was Russia’s only year-round maritime access, Bulgaria was in a much more important strategic position than Serbia. Nevertheless, in the summer of 1914, the St. Petersburg government had no option but to support Serbia if it intended to maintain a presence in the Balkan Peninsula.

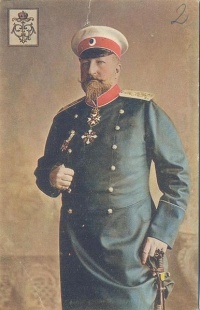

After the renewal and expansion of the fighting in the summer of 1914, both belligerent alliances recognized the importance of Bulgaria. For the Entente, an alliance with Bulgaria could greatly facilitate an attack on Constantinople and could support Serbia. For the Central Powers, the adherence of Bulgaria would ensure land communication with the Ottoman Empire and the likely destruction of Serbia. Despite the national bitterness against Serbia as well as the personal inclinations of the Austro-German Bulgarian Ferdinand I, Tsar of Bulgaria (1861-1948) and the German-educated Bulgarian Prime Minister, Radoslavov, the Sofia government was prepared to intervene on whichever side would guarantee the attainment of Bulgaria’s nationalist objectives, especially in Macedonia.

Entry into World War I↑

In 1915, the Gallipoli campaign made Bulgaria particularly attractive to the Entente. A Bulgarian advance on Constantinople could ensure an Entente success in their effort against the Ottomans. The Bulgarians after all, had reached the outer defenses of Constantinople during the First Balkan War. The defeat of the Ottoman Empire could open up a year-round sea route to the beleaguered Russians. The price for Bulgarian intervention on the side of the Entente was Macedonia. Because the Serbs were unwilling to cede Macedonia, especially after the 1914 defensive victories against Austria-Hungary, the Entente could not meet the Bulgarian demand. Serbia, after all, was the ally whose distress had been a main cause for the outbreak of the war. At best, the Entente could offer Bulgaria the Enos-Midia line in eastern Thrace and part of Macedonia after the war, when Serbia presumably would have obtained Bosnia-Herzegovina, Dalmatia, and Vojvodina from the Habsburg Empire.

No such constraints hampered the Central Powers. The Austro-Hungarians and Germans indicated that Bulgaria could have Macedonia immediately upon entering the war.[7] By the summer of 1915, with the apparent failure of the Entente at Gallipoli and the German victories on the Eastern Front at Gorlice-Tarnow, the choice appeared obvious. As Radoslavov stated at the time, “Bulgaria cannot be denied its historical and ethnographic rights. It cannot exist without Macedonia, for which it has shed so much blood.”[8] After some negotiation, the Central Powers agreed that Bulgaria could have part of Macedonia at the end of the war, or, all of it immediately. As an additional incentive, the Ottomans ceded the lower Maritsa valley to Bulgaria. This extended Bulgarian rule in western Thrace and gave Bulgaria control of the railroad line to Bulgaria’s only Aegean port, Dedeagach (Greek: Alexandroúpolis). In a treaty signed in Sofia on 6 September 1915, Bulgaria joined the Central Powers. On 15 September, the government announced mobilization of the army. Colonel Nikola Zhekov (1865-1949), was promoted to general at the beginning of August. He then assumed command of the Bulgarian army.

The renewal of the war was by no means popular in the country. A loose coalition of all opposition parties except for the narrow Socialist (Marxist) party met on 17 September with Tsar Ferdinand and demanded the formation of a wide coalition before the country embarked on another round of fighting.[9] At the meeting, Aleksandŭr Stamboliyski (1879-1923), the leader of the Agrarian Union (Peasant Party) warned the tsar that by entering the war he risked another disaster like the previous conflict. Ferdinand responded, “Don’t worry about my head, I am old. Think about your own, which is still young.”[10] Finally, Ferdinand said merely that he would inform Radoslavov of the meeting. Soon after this meeting, Stamboliyski was arrested and after a military trial sentenced to life imprisonment. The government then secured parliamentary sanction for the war based upon the need to destroy the Treaty of Bucharest and to obtain union with Macedonia.

World War Victories↑

The next month the Central Powers attacked Serbia from two sides. One Austro-Hungarian and one German army crossed the Danube and the Sava Rivers in the north on 6 October. Two Bulgarian armies attacked Serbia from the east one week later. The Bulgarian General Staff anticipated a relatively easy campaign. They were correct in this assumption. The combined Austro-Hungarian, Bulgarian, and German attacks soon overwhelmed the Serbs. By 5 November, the Bulgarian First Army seized Niš and met up with the oncoming German army. The Bulgarians then proceeded to defeat the Serbs on the historic battlefield of Kosovo Polje. Cut off from moving south, in November and December 1915, the remnants of the Serbian army retreated to the southwest across the Albanian mountains to the Adriatic Sea. Eventually the survivors of this ordeal found refuge on the Greek island of Corfu.

The Sofia government incorporated Macedonia directly into the state. The Bulgarian army raised an entire division from the population, the 11th Macedonian Division, and also smaller units. Over 1,300 Macedonians served in the Bulgarian army during the war.[11]

The Bulgarian military and government had not anticipated, however, the intervention of British and French forces in the Serbian campaign. Entente troops began landing on 7 October in neutral Greece at the port of Salonika on the invitation of the pro-Entente Greek Prime Minister Eleutherios Venizelos (1864-1936). Their plan was to move north up the Vardar River valley to aid the beleaguered Serbs. Near Strumitsa in Serbian Macedonia, they encountered the oncoming Bulgarian Second Army. The Bulgarians halted the British and French in a series of sharp engagements on both sides of the Vardar River and forced them back across the Greek frontier in December 1915.

At this point, the commander of the Bulgarian army, General Zhekov, urged an all-out attack on the disorganized Entente troops that were falling back towards Salonika. A strong Bulgarian effort could eliminate the Salonika operation altogether. Advocating to the German high command an attack on the Entente, he insisted, “We have committed our entire existence to this war, we have engaged in a bloody combat and have sustained enormous losses.”[12] This was a decisive moment for Bulgaria in the First World War. The presence of a large Entente force on Bulgaria’s southern frontier represented a significant danger not only to Macedonia, but also to the original Bulgarian national territory. The elimination of this Entente threat could have meant that for Bulgaria, the war was over, and Macedonia was secured. The Bulgarians were confident of success against the defeated and disorganized British and French troops who were falling back on Salonika. For the time being, they enjoyed a numerical advantage over the Entente forces.

The Germans refused to countenance the proposed Salonika operation. Fighting between Bulgarian and Entente forces on Greek territory could place Constantine I, King of Greece (1868-1923), the brother-in-law of Wilhelm II, German Emperor (1859-1941), in a difficult position. Also, the political situation in Greece had changed. A neutralist government had replaced the pro-Entente government in Athens early in October. Most importantly, the Germans perceived in Salonika a means to contain significant numbers of British and French troops that might be used to better effect elsewhere, perhaps on the Western Front.[13] Their success against the British and French was a source of great satisfaction to the Bulgarians. It might have persuaded them that there was no need to pursue the war further. Why would the Bulgarians continue to fight if they had attained their national objectives? Would they be willing to send troops to the Western or Eastern Fronts? The commander of the German forces, Erich von Falkenhayn (1861-1922), later wrote,

The Bulgarians could not ignore the insistence of their German allies. The Central Powers were not equal. Lacking an industrial infrastructure, the Bulgarians depended upon the Germans for manufactured goods, and especially military supplies. They reluctantly acceded to German demands to halt at the Greek frontier.

The failure to cross the Greek border and advance on the Entente determined the course of the rest of the war for Bulgaria. The Bulgarian army continued to confront Entente forces along the Greek frontier. This became known as the Macedonian, and later for the Bulgarians, the southern front. Gradually the manpower and material demands of this commitment eroded the already weak Bulgarian economy, and Bulgarian morale. Clearly, Bulgarian and German aims were at odds. Unfortunately, Bulgaria, as the smallest Central Power, had little leverage with the larger German war effort.

The Bulgarian halt at the Greek frontier allowed the Entente armies to establish defensive positions in northern Greece at the beginning of 1916. Throughout that year, the Entente augmented its forces in Salonika with additional British and French troops as well as contingents from Italy and Russia. Eventually, after some rest and refurbishment on Corfu, the survivors of the Serbian retreat across northern Albania joined the Entente army in Salonika. At various times this force included British, French, French Colonial (among which were Malagasy, Senegalese, and Vietnamese personnel), Italian, Russian, and Serbian troops. In 1917, after the Entente had forced King Constantine to abdicate and Venizelos had returned to power, the Greek army joined the Entente and sent troops to bolster the Macedonian Front. Eventually the Macedonian Front extended from the Adriatic Sea to the Aegean. Austro-Hungarian troops manned it in Albania, then a mainly Bulgarian force with German command, the German Eleventh Army, then the Bulgarian First and Second Armies. To the great alarm of the Bulgarians, two Ottoman divisions assumed positions on the eastern end of the Macedonian Front from the autumn of 1916 to the spring of 1917. Thus at one time all the Central Powers were represented there. Throughout its existence, the Bulgarians were numerically the largest Central Powers’ force on the Macedonian Front. The Macedonian Front developed in the pattern already established on the Western Front: both sides fortified their positions and sought advantage in air raids and small ground attacks.

In the summer of 1916, the apparent success of the Brusilov offensive on the Eastern Front altered the situation throughout Eastern Europe. The Russians smashed the Austro-Hungarian army in Galicia. The Germans rushed reinforcements to support their failing allies. Romania, which had wavered between each side since the beginning of the war, appeared ready take advantage of the Austro-Hungarian emergency to join the Entente. Both sides prepared to deal with this development. The Entente readied an offensive along the Macedonian Front to divert the Central Powers from Romania, which lay exposed between Austria-Hungary and Bulgaria.

The Central Powers also took action. The pending threat from Romania persuaded the Germans to lift their ban on a Bulgarian advance into Greece. The Bulgarians attempted to preempt the anticipated Entente offensive on the Macedonian Front by launching one of their own. This Bulgarian effort involved attacks on the eastern and central sections of the Macedonian Front. In the east, Bulgarian troops advanced into Greek-held eastern Macedonia. Against little British and Greek resistance, they occupied Drama, Seres, and the Aegean port of Kavala. In the center, they seized Florina (Bulgarian: Lerin). The Entente counterattacked the Bulgarians around Florina, and throughout the autumn of 1916 drove the Bulgarians north into Macedonia as far as Bitola (English: Monastir).

As all had anticipated, on 27 August Romania entered the war on the side of the Entente and invaded Transylvania. The Bulgarian Third Army, augmented by German and Ottoman troops and under the overall command of the German General, August von Mackensen (1849-1945), crossed the Romanian frontier in Dobrudzha at the same time as an Austro-Hungarian and German counterattack on the Romanians in Transylvania. The Bulgarians advanced quickly against determined Romanian opposition. In October, they had defeated a Romanian attempt to cross the Danube to invade Bulgaria. By November, the Bulgarian Third Army had overrun all of Dobrudzha to the mouth of the Danube and the Central Powers had occupied all of southern Romania. The Romanians held only the northeastern part of their country, which they governed from Iaşi. When Russia dissolved into chaos in 1917, rump Romania was isolated from the other Entente powers. This position was untenable. The Romanian government signed the Treaty of Bucharest on 7 May 1918 and left the war soon after the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk eliminated Russia from the war.

The results of the fighting in 1916 were mixed for Bulgaria. Bulgarian soldiers had occupied eastern Macedonia, but had retreated from central Macedonia under Entente pressure. The Romanian danger was eliminated, but Bulgaria soon became embroiled in disputes with the other Central Powers over the disposition of Dobrudzha and its resources. The Third Army remained in Romania for the time being to enforce Bulgarian claims to all of Dobrudzha. The Radoslavov government was especially eager to supplement dwindling Bulgarian food resources with Dobrudzha grain. In 1916, the Bulgarians were crucial to the stability of the Macedonian Front and the containment of Romania. Their actions expanded the position of the Central Powers throughout southeastern Europe. They now, however, faced a two front war. Bulgaria was squeezed between southern and northern fronts.

Erosion of Bulgarian Strength↑

During 1917, the Bulgarians continued to hold the Macedonian Front. Their dwindling resources permitted mainly defensive activity. Only in the spring did significant fighting occur there, mainly around Lake Doiran, between the Bulgarians and the British forces. At that time, the Bulgarians succeeded in parrying another Entente offensive. Despite the absence of heavy fighting, war weariness continued to erode the commitment of the Bulgarian army and people to the military effort. Several factors played a role in the deterioration of Bulgarian morale. The duration of the war was an important factor in this decline. Bulgarians had been at war more or less since 1912.

Disputes over the disposition of conquered territory and available resources persisted between Bulgaria and all three Central Powers allies. Particularly sharp was the disagreement over the disposition of Dobrudzha and its food resources. Only in September 1918 did the Bulgarians gain the recognition of their Central Powers allies of Bulgarian control of most of this region. By then it was too late to realize any advantage.

The 1917 revolutions in Russia attracted also a great deal of attention in urban areas in this traditionally Russophile country. The Bulgarian army had occasionally fought the Russians in both Dobrudzha and Macedonia, but Bulgarian interest in the largest Orthodox Slavic power remained strong. However, the predominately peasant population had less interest in proletarian revolution. The peasants were more concerned with growing adequate food crops and in obtaining proper compensation for their efforts. This did not always mean that the urban population was well fed. German speculators and troops used their cash to buy much of the Bulgarian agricultural production and send it out of the country. After the war, state trials indicated that although the Germans had 16,000 to 18,000 men on the Macedonian Front they drew rations for 100,000 men, mainly from Bulgarian sources.[15] This increased the widespread food shortages and inflation. Hunger appeared throughout Bulgaria. Naturally, the growing food crisis adversely affected military morale. In an attempt to deal with these issues, the Sofia government established a Directorate for Economic and Social Welfare headed by General Aleksandŭr Protogerov (1867-1928) in 1917.[16] Despite the Directorate’s efforts, Bulgaria’s food and materiel problems persisted. Like most other First World War combatants at this time, Bulgaria experienced severe war weariness. Epidemic disease and inherent corruption added to the misery of the home front. Efforts by women’s organizations eased but could not eliminate these travails.[17]

The food and material crises raised important questions as to Bulgaria’s ability to continue its war effort. During the summer of 1917, opposition elements including members of the Agrarians and General Zhekov discussed the overthrow of the Radoslavov government.[18] The general was not prepared at this point to take such radical action.

In 1918, material conditions in Bulgaria and at the front deteriorated further and the erosion of Bulgarian morale increased. One reason for the intensification of war weariness was the German focus on the Western Front. As they prepared for their great Western Front offensive, the Germans shifted most of their forces and much of their equipment away from Macedonia in late 1917. By the summer of 1918, only thirty-two German batteries and three battalions, mainly of light infantry, remained there.[19] The transfer of most of the units of the Bulgarian Third Army from Dobrudzha to Macedonia did not make up for the loss of the Germans. General Zhekov warned that these German measures, "would cause the army and the Bulgarian people to feel that our front is being deserted at a time when we are confronting new enemies and when serious problems are at hand for us on the Macedonian Front."[20] He feared that the Bulgarian army was nearing the point of exhaustion and could not hold on to Macedonia without greater German assistance.

The food problem worsened from 1917 to 1918. Only low quality bread, made mainly from corn meal and sometimes augmented by ground corn husks, was available for the troops. After a tour of the front in June 1918, General Zhekov reported to Tsar Ferdinand, that, "The lack of food, mainly bread and meat, causes alarming unease and makes morale plummet."[21] There was also a dearth of clothing and footgear. Some Bulgarian soldiers went into battle barefoot and in rags.

In the same report, Zhekov urged Ferdinand to replace the Radoslavov government. By this time, the prime minister had lost support throughout the country. The final issue leading to the dismissal of the Radoslavov government was its failure to obtain all of Dobrudzha at the Treaty of Bucharest.[22] The Bulgarian military and public regarded this region as inherently Bulgarian, and vital to the easing of the ever-increasing food shortages. All of Bulgaria’s allies sought to maintain their own interests in Dobrudzha. This included the Ottomans, who had participated in the 1916 campaign and who still maintained troops there. Somewhat reluctantly, Ferdinand forced Radoslavov to resign on 20 June. A coalition government led by former Prime Minister Aleksandǔr Malinov (1867-1938) assumed power on 27 June. There was little Malinov could do, however, to alleviate the desperate domestic circumstances. By this time, many of the women on the home front had begun to organize against the war.[23] Also, as the Central Powers began to implode, Malinov could wield little influence within the alliance.

Particularly problematic were Bulgaria’s already failing relations with their Ottoman allies. The Bulgarian relationship with their former overlords and Balkan War enemies had never been easy. After the 1915 agreement, the Ottomans quickly regretted the cession of the Maritsa valley to Bulgaria and began to raise the issue of its return after the Bulgarian occupation of Macedonia. At the end of 1916, they began to raise the issue and to press for the Bulgarian cession of all of Thrace.[24] A formal Ottoman request for the return of western Thrace arrived in Sofia in July 1918.[25] The Ottomans justified this on the basis of their efforts in Dobrudzha. This was completely unacceptable to the Bulgarians. The Central Powers alliance in southeastern Europe was on the verge of collapse because of this issue.

Defeat in World War I↑

A combined French and Greek attack on Bulgarian positions in the middle of the Macedonian Front at Yerbichna (French and Greek: Skra di Legen) in June 1918 demonstrated the extent of demoralization of the Bulgarian forces. The usual counterattacks were aborted because soldiers lacked basic items such as boots, and because the morale of the troops was problematic. The Bulgarian failure at Yerbichna was a portent for the fatal events of September 1918. General Zhekov did not attempt to conceal the poor condition of the Bulgarian army from his German allies. He warned the German commander Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg (1847-1934): "I am seriously concerned whether we, with our weakened forces and paltry means, are in condition to resist to the end a powerful attack from our more numerous enemies."[26] Zhekov asked for greater German assistance in materiel and manpower. Because the Germans were heavily engaged on the Western Front by this time, no help was forthcoming. The Bulgarians understood that they were in a difficult position. At the same time, they recognized that the war would not be won on the Macedonian Front. It could, however, be lost there.

By this time, the cumulative situation for Bulgaria was becoming impossible. A Bulgarian non-commissioned officer bluntly told General Zhekov on 20 July 1918: “We are naked, barefoot and hungry. We will wait a little longer for clothes and shoes, but we are seeking a quick end to the war. We are not able to hold out much longer.”[27] Rumors circulated throughout the Bulgarian ranks that soldiers would be released from active duty on 15 September on the third anniversary of Bulgaria’s mobilization.

On 14 September 1918, the day before this anniversary, French and Serbian forces launched a massive assault on Bulgarian defenses at Dobro Pole, a heavily fortified ridge west of Yerbichna in the middle of the Macedonian Front. After two days of heavy fighting, the Bulgarian positions crumbled and Bulgarian soldiers began to retreat in disarray.[28] This occurred at a part of the front where two Bulgarian divisions came under the command of the German Eleventh Army. This arrangement was largely a means to demonstrate continued German involvement at the Macedonian Front. They provided the headquarters staff and a few specialists for the Eleventh Army while the Bulgarians supplied most of the soldiers. Discipline in the 2nd Thracian and the 3rd Balkan Divisions collapsed. French and Serbian troops surged north through the resulting gap into Macedonia. Few Central Powers reserves existed to deal with the situation. Those Bulgarian forces remaining under discipline were too far east or west to block the advance of the Entente troops. Lateral movement over the difficult terrain was impossible. By then most German troops on the Western Front were retreating. After the Bulgarian disintegration at Dobro Pole, the way north for the French and Serbs was open. Serbian troops could return home. The undefended southern frontier of Austria-Hungary became vulnerable to Entente attack.

Nevertheless, even after the Entente breakthrough at Dobre Pole, some Bulgarian units achieved notable military success. On 18 September, the Bulgarian First Army’s 9th Pleven Division defeated a joint British and Greek offensive east of Dobro Pole, near Lake Doiran.[29] This victory indicated that despite their low morale, Bulgarian soldiers were still capable of a sustained defensive effort. Bulgarian forces in western Macedonia also maintained their positions against scattered Entente attacks.

Despite the defensive victory at Lake Doiran, Bulgarian units at the front to the east and west of Dobro Pole had to withdraw to avoid being cut off by the oncoming French and Serbian armies. Indiscipline spread through many units. Almost six years of fighting, lack of food and clothing, and concerns about their families at home caused many Bulgarian soldiers to reject frantic attempts by their officers to impose discipline. Disorganized mobs of Bulgarian soldiers moved north, determined to punish those in Sofia whom they regarded as responsible for all the suffering at home and at the front. Many of these mutinous soldiers came under the influence of peasant revolutionary leaders from the Agrarian (Peasant) Party: men such as Aleksandŭr Stamboliyski, whom the government had recently released from confinement in an effort to ease the situation. Bulgaria appeared to be on the way to emulating the Russians and carrying out their own revolution. The Austro-Hungarians and Germans could promise only that six divisions were on the way from the Italian Front and distant Crimea.

With revolution threatening and effective help from the Central Powers lacking, the Bulgarian government sought a way out of the war. Few good options were available. Tsar Ferdinand somewhat histrionically explained the situation to Charles I, Emperor of Austria (1887-1922):

Under these circumstances, the Bulgarian government decided on 25 September to seek an accommodation with the Entente. It dispatched a delegation to Salonika to negotiate. Accompanying this delegation was the American Consul General in Sofia, Dominic I. Murphy (1847-1930). The Bulgarians hoped that because they had never declared war on the United States, the American diplomat could help mitigate the armistice conditions.[31] Unfortunately, they were in no position to prevail in these talks. Despite the American diplomatic presence, the Bulgarians had to accept all the Entente demands, including the free passage of Entente soldiers through Bulgarian territory; the right of British and French troops (though not Greek or Serbian) to occupy some strategic points within the country; the end of relations with the other Central Powers; and the repatriation of prisoners of war.[32] These terms were not terribly onerous. Most of Bulgaria avoided foreign occupation. Any such foreign presence would have been much worse if Greek and Serbian soldiers had been involved. The Bulgarian delegation signed an armistice agreement with the Entente on 29 September in Salonika. Bulgaria became the first of the Central Powers to leave the war. Already Entente members Montenegro, Russia, and Romania had preceded Bulgaria in leaving the war. While after the summer of 1916 Entente military strength on the Macedonian Front was superior to that of the Bulgarians, the years of bad food, shoddy materiel, and uncertain relations with their allies proved to be as effective a weapon as the Serbian infantry and French artillery in the defeat of September 1918.

After the First World War, some Germans blamed the Bulgarians for the collapse of the Central Powers in the fall of 1918. General Erich Ludendorff (1865-1937), who directed the German war effort after 1916, later wrote that “We were not strong enough to hold our line in the West and at the same time to establish in the Balkans a German front to replace the Bulgarian.”[33] Ludendorff’s commander-in-chief, General Paul von Hindenburg, was just as scathing in his memoirs about his erstwhile Bulgarian allies. He wrote,

Germany lacked the resources to hold both places. In fact, the German army had been in retreat in the west since August. The Bulgarians held out in the war longer than the Russians or Romanians. They collapsed under direct assault from a major offensive only a month before the Ottomans, five weeks before the Austro-Hungarians and six weeks before the Germans.

Ironically, after the signing of the armistice, newly arrived German troops together with Bulgarian officer cadets defeated the revolutionaries outside of Sofia. Tsar Ferdinand abdicated on 3 October 1918 in favor of his son, who became Boris III, Tsar of Bulgaria (1894-1943), and left the country, never to return. At this point, with the war now over, most of the disaffected Bulgarian soldiers simply went home. This was their original goal after all.

The next year Stamboliyski, the revolutionary leader, became the Bulgarian prime minister. On 27 November 1919, the Bulgarians signed the Treaty of Neuilly. Dobrudzha reverted to Romania and Macedonia to the new Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes (Yugoslavia) along with several small territories along Bulgaria’s western frontier. In addition, Bulgaria lost its Aegean coastline to Greece. Finally, Bulgaria was limited to an army of 20,000 and had to pay reparations of 445 million dollars. In 1923, Bulgarian nationalists, angry at Stamboliyski’s apparent disinterest in Macedonia and his attempts to achieve a rapprochement with the new Yugoslav kingdom, murdered him. In 1941, Bulgaria joined the Axis powers on the promise of obtaining Macedonia. By 1944, the Red Army occupied the country and installed a pro-communist government, which foreswore the gains of the Nazi alliance. For the third time in a little over thirty years, Bulgaria suffered defeat and disappointment over Macedonia. The Bulgarians did regain southern Dobrudzha with Nazi assistance in 1940, and retained it with Soviet sanction in 1947.

Conclusion↑

Relative to its small size and population Bulgaria played an extremely important role in the First World War. For almost three years, the bulk of the Bulgarian army, augmented by some Austro-Hungarian, German, and for a while, Ottoman units, contained a large Entente force north of Salonika. Bulgarian troops manned positions stretching from Lake Prespa in central Macedonia to the Aegean Sea to the mouth of the Struma River. The Bulgarians also contributed another force for the defeat and occupation of Romania. These efforts placed a huge burden on the limited resources of the Bulgarian state. On the eve of the battle of Dobro Pole, the Bulgarians had reached “the peak” of their general mobilization with 878,000 men in uniform, of which 697,000 were in the military.[35] This means that virtually every Bulgarian male of military age was in uniform. The Bulgarian army was a veteran force due to its participation in the Balkan Wars. In the First World War it committed two armies to the campaign that overran Serbia. This victory thus established a direct connection between the Austro-German and Bulgarian-Ottoman parts of the Central Alliance. After this success the Bulgarian army held in place 300,000 Entente soldiers who might have been utilized on the Western Front or elsewhere. Without the participation of Bulgaria in its ranks, the Central Powers might not have held out until the autumn of 1918 against the Entente. Surely, the German connection to the Ottoman Empire would have remained tenuous, and the Romanian threat to Austria-Hungary might have proved viable. Had the Bulgarians not endured as long as they did on the Macedonian Front, an Entente thrust could have broken through and brought about the collapse of the other Central Powers allies against the more numerous, better-fed and better-equipped Entente opponents as early as 1916.

Richard C. Hall, Georgia Southwestern State University

Section Editors: Milan Ristović; Tamara Scheer

Notes

- ↑ Helmreich, Ernst Christian: The Diplomacy of the Balkan Wars 1912-1913, New York 1966, pp. 53-56.

- ↑ On the fighting at Chataldzha see Hall, Richard C.: The Balkans Wars 1912-1913, Prelude to the First World War, London 2000, pp. 32-38; on Adrianople see ibid., pp. 86-90.

- ↑ Hall, Balkan Wars 2000, pp. 123-125. The Bulgarians and the Ottomans signed a separate treaty in Constantinople on 30 September 1913, which recognized Ottoman control over most of eastern Thrace. See: Hall, Balkan Wars 2000, pp. 125-127.

- ↑ On this transfer of power from the Russophile government of Danev to the Russophobe government of Radoslavov see Kishkolova, Pasha: Bŭlgariya 1913, Krizata vǔv vlastta [Bulgaria 1913, The Government Crisis], Sofia 1998.

- ↑ Hoetzsch, Otto (ed.): Die internationalen Beziehungen im Zeitalter des Imperialismus: Dokumente aus den Archiven der Zarischen und der Provisorischen Regierungen, Berlin 1942, I/4 no. 311. Nicholai Schebeko (1863-1953) was the Russian minister in Bucharest in 1913 and the Russian representative at the Bucharest peace talks.

- ↑ Hall, Richard C.: Bulgaria’s Road to the First World War, Boulder 1996, pp. 266-268.

- ↑ Hall, Bulgaria’s Road 1996, p. 295.

- ↑ Ministerstvo na vŭnshnite raboti i na izpovedaniyata: Diplomaticheski dokumenti po uchastieto na Bŭlgariya v Evropeiskata voina [Ministry for Foreign Affairs and Religion, Diplomatic Documents on the participation of Bulgaria in the European War], Sofia 1921, volume I, numbers 798, 822, 849.

- ↑ Crampton, R.J.: Bulgaria 1879-1918, Boulder 1983, p. 448.

- ↑ Bell, John: Peasants in Power, Alexander Stamboliyski and the Bulgarian Agrarian Union, 1899-1923, Princeton 1977, p. 120.

- ↑ Minchev, Dimitre (Dimitǔr): The Bulgarian Army at the Salonica Front, in: The Salonica Theatre of Operations and the Outcome of the Great War, Thessaloniki 2005, p. 133.

- ↑ Archive of Ferdinand, Tsar of Bulgaria, Hoover Institute, Stanford, California (hereafter referred to as Archive of Ferdinand), 53-7 (1915), Dorbrovitch palais Sofia za General Gekoff [Dobrovich in the Palace for General Zhekov] (sic, this was evidently a mistransliteration of Zhekov) , 22/12 December 1915, pp. 2-3.

- ↑ Kamburov, Gencho: Voennopoliticheskite otnosheniya mezhdu Bŭlgariya i Germaniya prez Pŭrvata svetovna voina [Military and Political Relations between Bulgaria and Germany during the First World War], in: Bŭlgarska akademiya na naukite, Bŭlgarsko-Germanski otnosheniya i vŭzki [Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Bulgarian-German Relations and Connections], Sofia 1972, volume I, pp. 252-257.

- ↑ Falkenhayn, Erich von: The German General Staff and its Decisions 1914-1916, New York 1920, p. 216, online: https://archive.org/stream/germangeneralsta00falk#page/216/mode/2up (retrieved 26 January 2016).

- ↑ Logio, George Clenton: Bulgaria Past and Present, Manchester 1936, p. 418.

- ↑ Crampton, Bulgaria 1983, pp. 499-506.

- ↑ See Dimitrova, Snezana: For Social Justice and Welfare: Hunger, Diseases, and Bulgarian ‘Women’s Revolts’ (1916-1918), in: Höpken, Wolfgang/Meurs, Wim van (eds.): The First World War and the Balkans – Historic Event, Experience and Memory, Munich 2015, pp. 13-16.

- ↑ Crampton, Bulgaria 1983, pp. 458-459.

- ↑ Dieterich, D.: Weltkriegsende an der mazedonischen Front, Berlin 1928, p. 17.

- ↑ Archive of Ferdinand, 72-3 (1918), correspondence, General-Leitenant Zhekov to Polkovnik Ganchev, 12 April 1918, p. 2.

- ↑ Archive of Ferdinand, 70-1 (1918), Military Affairs, Doklad do Negovo Velichestvo Tsarya of General Zhekov [Report to His Majesty the Tsar by General Zhekov], 12 June 1918, p. 4. Underlining in the original.

- ↑ Crampton, Bulgaria 1983, p. 466.

- ↑ Dimitrova, Social Justice 2015, pp. 17-19.

- ↑ Hall, Richard C.: Balkan Breakthrough, the Battle of Dobro Pole 1918, Bloomington 2010, pp. 92-93.

- ↑ Archive of Ferdinand, 69-7 (1918), report of 13 July 1918.

- ↑ Archive of Ferdinand, 70-1 (1918), Military Affairs, telegram from General Zhekov to Tsar Ferdinand, 15 July 1918.

- ↑ Toshev, S.: Pobedeni bez da bŭdem biti [Lost Victories], Sofia 1924, p. 198.

- ↑ Hall, Balkan Breakthrough 2010, pp. 126-145.

- ↑ See Karaivanov, Asen: Otbranata na Doiranskata pozitsiya prez Septemvi 1918 godina [The Defense of the Doiran Position during September 1918], Voennoistoricheski sbornik [Military History Journal] (1988), pp. 129-139; and Lieutenant-Colonel Nédev, Les opérations en Macédoine, L'épopée de Doïran 1915-1918, Sofia 1927, pp. 222-282. The Bulgarian defensive successes in the 1917 and 1918 battles remain a source of national pride. See for instance Nedev, Nikola: Doiranskata epopeya 1915-1918 [The Doiran Epic 1915-1918], Sofia 2009. This is an updated and profusely illustrated edition of the previous work.

- ↑ Archive of Ferdinand, 74-2 (1918), correspondence, incoming, telegram of Ferdinand to Emperor Karl, 25 Sept 1918. General Stefan Nerezov (1867-1925) commanded the Bulgarian First Army.

- ↑ Petkov, Petko M.: SASHT i Bŭlgariya 1917-1918 [The USA and Bulgaria 1917-1918], Godishnik na Sofiiskiya universtet, Istoricheski fakultet 73 (1970), p. 99.

- ↑ Todorova, Tsvetlana (ed.): Bŭlgariya v Pŭrvata svetovna voina, Germanski diplomaticheski dokumenti [Bulgaria in the First World War: German Diplomatic Document], Sofia 2005, volume 2, Prilozhenie number 1, 29 September 1918, pp. 714-715; number 505, 1 October 1918, p. 1090.

- ↑ Ludendorff, Erich von: Ludendorff’s Own Story, New York 1919, volume II, p. 368, online: https://archive.org/stream/ludendorffsowns02ludegoog#page/n382/mode/2up (retrieved 26 January 2016).

- ↑ Hindenburg, Paul von: Out of my Life, London 1920, p. 404, online: https://archive.org/stream/outofmylife00hinduoft#page/404/mode/2up (retrieved: 26 January 2016).

- ↑ Markov, Georgi: Golyamata voina i Bŭlgarata straha mezhdu Sredna Evropa i Orienta [The Great War and Bulgaria in Fear between Central Europe and the East], Sofia 2006, p. 288. Railroad employees and other critical groups of workers were considered mobilized.

Selected Bibliography

- Bell, John D.: Peasants in power. Alexander Stamboliski and the Bulgarian Agrarian National Union, 1899-1923, Princeton 1977: Princeton University Press.

- Crampton, Richard J.: Bulgaria 1878-1918, Boulder; New York 1983: East European Monographs.

- Hall, Richard C.: The Balkan Wars 1912-1913. Prelude to the First World War, London; New York 2000: Routledge.

- Hall, Richard C.: Balkan breakthrough. The Battle of Dobro Pole 1918, Bloomington 2010: Indiana University Press.

- Helmreich, Ernst Christian: The diplomacy of the Balkan wars, 1912-1913, Cambridge; London 1938: Harvard University Press; H. Milford, Oxford University Press.

- Markov, Georgi: Golyamata voina i Bŭlgariata straxha mezhdu Sredna Evropa i Orienta 1916-1919 g. (The Great War and Bulgaria in fear between Central Europe and the East 1916-1919), Sofia 2006.

- Markov, Georgi: Golyamata voyna i bǔlgarskiyat klyuch kǔm evropeyskiya pogreb 1914-1916 g. (The Great War and the Bulgarian key to the European powder keg 1914-1916), Sofia 1995.