Preliminaries↑

The Ottoman Empire entered the 20th Century in a decayed state, a weakness that contributed to the significant loss of territory to Italy and the Balkan League between 1911 and 1913.[1] Hoping to reverse Ottoman decline, the ruling Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) Party headed by Enver Bey (1881-1922) invited Imperial German advisors under General Otto Liman von Sanders (1855-1929) to reform the Ottoman military using the lessons of the Balkans Wars.[2]

In reaction to the Habsburg-Serbian conflict of July 1914, the Ottomans entered into a secret alliance with Imperial Germany and defensively mobilized in August 1914.[3] Under pressure from Germany, Enver authorized a naval sortie against Russian Black Sea installations on 29 October before issuing a formal declaration of war against the Triple Entente on 31 October 1914.[4]

Allied Plans↑

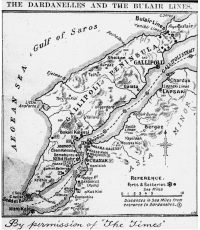

On 3 November 1914, British First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill (1874-1965) ordered British warships to shell Ottoman defenses along the Dardanelles strait – the waterway separating Çanakkale province into the Gallipoli (Gelibolu) peninsula and the Asian mainland – but the bombardment only served to intensify Ottoman defensive efforts under the overall direction of General von Sanders.[5] Churchill then convinced the British Secretary of State for War, Field Marshall Lord Horatio Kitchener (1850-1916), to support a joint offensive to breach the Dardanelles and seize Constantinople. From an initial apportionment of one division, the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force (MEF) under General Sir Ian Hamilton (1853-1947) grew to five divisions.[6]

Ottoman Defensive Preparations↑

By March 1915, Cevat Pasha (1870-1938), commander of the Çanakkale Fortified Area, had fully integrated 230 mobile guns and howitzers with the 82 fixed guns of the Dardanelles Fortress Command.[7] The Ottoman navy concurrently sowed dense minefields across the Dardanelles, and positioned a light gunboat flotilla to defeat enemy minesweeping attempts. To coordinate the landward Gallipoli defenses, the Ottoman army activated the III Ottoman Corps of three infantry divisions under Esat Pasha (1862-1952).[8]

Initial Actions↑

Led by British Admiral Sir Sackville Hamilton Carden (1857-1930), an Allied squadron of fourteen capital ships began shelling the Dardanelles defenses on 19 February 1915. Ottoman artillery and minefields, bad weather and technical limitations hindered the operation such that the ailing Carden was replaced by Vice Admiral John de Robeck (1862-1928). On 18 March 1915, de Robeck attempted a coup de main, which failed with heavy capital ship losses from Ottoman mines and shellfire. Hamilton witnessed the repulse, and with agreement from de Robeck and Kitchener, moved forward with preparations for an amphibious assault to clear the Ottoman defenses of the Dardanelles.[9] General von Sanders anticipated such an assault by activating the Ottoman Fifth Army headquarters to improve command and control of the Çanakkale regional defenses.[10]

Hamilton planned a multi-pronged assault on Gallipoli to seize the Kilid Bahr plateau overlooking the Ottoman defenses of the strait. Beaches on Gallipoli were small and separated, which necessitated landing the ANZAC (Australia and New Zealand) corps near Gaba Tepe (“Z” beach), while the British 29th Division would storm “S,” “V,” “W,” “X” and “Y” beach at Cape Helles. To overwhelm the Ottoman defenders, Hamilton planned simultaneous landings at Gallipoli, supported by feints at Bulair by the Royal Naval Division and Kumkale by the French 1st Division.[11]

The Initial Assault on Gallipoli↑

On 25 April 1915, the Royal Navy midshipman leading the ANZAC assault prevented a massacre at the heavily defended Gaba Tepe beaches by diverting the boats to the lightly defended Ariburnu (Anzac Cove).[12] However, the sluggish ANZAC advance allowed Lt. Col. Mustafa Kemal (1881-1938) time to contain the Ariburnu bridgehead by deploying the Ottoman 19th Division atop the commanding Sari Bair and Chunuk Bair ridges. Despite inflicting bloody losses on the British assault troops at Helles, the Ottoman defenders failed to prevent the enemy from establishing shallow lodgments. The British landing at ‘Y’ beach temporarily outflanked the Helles defenses, but Hamilton’s subordinates failed to exploit the breach before Kemal could deploy reinforcements atop the high ground near Krithia. General Esat of III Corps cemented Kemal’s success by sending reinforcements and regrouping divisional boundaries to give Kemal sole control of the Anzac sector.[13]

Major Operations↑

On 28 April 1915, the British 29th Division under General Aylmer Hunter-Weston (1864-1940) launched the First Krithia (Kirte) offensive to expand the Helles lodgment, but the assault failed with over 3,000 casualties. From 1-4 May, Esat Pasha’s III Corps hurled heavy but uncoordinated night attacks which failed to destroy the enemy lodgments at Helles. Hamilton’s second Krithia offensive of 6-8 May fared no better against the increasingly complex Ottoman defenses overlooking Cape Helles.[14]

After a visit to the front, Enver Pasha released fresh reserves to Sanders, along with orders for a renewed assault against Ariburnu by Esat’s Ottoman III Corps.[15] Esat launched a night attack on 19-20 May 1915, but the alert Allied defenders inflicted about 10,000 Ottoman casualties among the 50,000-man force – losses that compelled Esat to obtain a 24 May ceasefire to bury the rapidly decomposing corpses. Esat’s failure was offset when Ottoman naval mines and torpedoes sank several Entente capital ships, a morale-breaking Allied defeat that caused de Robeck to withdraw his surviving capital ships to safer waters.[16] On 4 June, a daylight attack by four Allied divisions against 25,000 Ottoman defenders, the Third Battle of Krithia, failed to penetrate the Ottoman defenses; clear evidence the campaign had fallen into stalemate.[17]

On 6-7 August 1915, Hamilton launched a surprise breakout attempt at Helles and Anzac, in concert with an amphibious assault at Suvla Bay by the fresh IX Corps under General Sir Fredrick Stopford (1854-1929). German Major Wilhelm Willmer skillfully employed his “Anafarta Group” of Jandarma (gendarmerie) to delay Stopford’s green troops until reinforcements from the Ottoman Fifth Army arrived to contain the Suvla bridgehead.[18] Hamilton remained aloof as the battle unfolded and intervened to replace the plodding Stopford only after the IX Corps failed to seize the commanding Anafarta Hills. By failing to define clear operational level objectives, and to exercise close supervision of Stopford’s tactical actions, Hamilton squandered his last opportunity for an operational level victory at Gallipoli.[19]

The End of the Campaign↑

The Ottoman success at Gallipoli encouraged Bulgaria’s mobilization for war in September 1915, causing the Allies to divert reinforcements from Gallipoli to support the Serbian army. Hamilton was relieved of command in October 1915 after rejecting proposals for withdrawal. Hamilton’s replacement, Lt. Gen. Sir Charles Monro (1860-1929), was appalled at the precarious state of the Allied lodgment and urged a total withdrawal of Gallipoli to Kitchener. The quick collapse of the Serbian army, and subsequent arrival of German heavy guns at Gallipoli compelled the British War Cabinet to authorize a withdrawal.[20]

In contrast to the muddled landings, the Allied evacuations in late December and early January 1916 were well planned and successfully executed by Monro’s replacement, General William Birdwood (1865-1951).[21] The Gallipoli campaign produced an estimated half-million casualties: 205,000 Commonwealth, 47,000 French, and 251-289,000 Ottoman. Of those totals, estimated Allied dead and missing were 47,000, while the Ottomans calculated 56,643 dead, and 11,176 missing.[22]

Analysis↑

To this day, historians are still divided over the strategic merits of the Gallipoli campaign.[23] The reputations of the principle British commanders were ruined, and British Prime Minister H. H. Asquith’s coalition government was internationally discredited. During the campaign, Allied operational and tactical actions were often marred by incompetent leadership and lack of joint- and combined cooperation. By contrast, German and Ottoman leaders were generally competent, and quicker to recognize and exploit tactical opportunities. Victory restored the prestige of the Ottoman army, with Mustafa Kemal lionized as a national hero. The Dardanelles remained closed to Entente shipping for the rest of the war, a key factor in the breakdown of the Russian war effort in late 1916.[24]

The Legacy of Gallipoli↑

Following the Armistice of Mudros in October 1918, the Allies partitioned the Ottoman Empire, and occupied Istanbul and Gallipoli. The humiliating capitulation eclipsed the victory at Gallipoli, and no official commemorations were held in the immediate postwar period.[25] During the Turkish War of Independence (1919-1923), Mustafa Kemal (later Atatürk) emerged as the leader of the nationalist faction, which established the modern independent Turkish Republic.[26] Afterwards, official narratives emphasized the role of Atatürk and his Turkish soldiers in Gallipoli victory, while Enver and the other CUP leaders were blamed for the ultimate Ottoman defeat. Aside from the official histories of the Turkish General Staff, the role of Esat, other Ottoman officers, and the non-Turkish troops of the old empire faded from public memory of Gallipoli.[27] Turkish memorialization of the Gallipoli battlefields and fallen Ottoman soldiers did not begin until 1943 in a fitful process that stretched into the 1990s. Despite widespread public pressure, the Turkish government did not officially commemorate the 18 March 1915 Dardanelles naval victory until 1981.[28]

Gallipoli deeply influenced the national memory and identity of Australia and New Zealand, with each nation designating 25 April as ANZAC Day, a day of national remembrance.[29] Initial accounting and commemoration for the war dead buried at Gallipoli was delayed until the end of the Turkish Wars for Independence in 1923. Unlike the Western Front, where the Commonwealth consolidated its war dead in large national cemeteries, the war cemeteries on Gallipoli remained generally untouched except for the addition of unobtrusive commemorative markers.[30] French participation in the Gallipoli campaign was overshadowed by the memories of the Western Front; consequently, the French war dead of Gallipoli were commemorated with but a single monument.[31]

Harold Allen Skinner Jr., United States Army Soldier Support Institute, and Liberty University

Section Editor: Erol Ülker

Notes

- ↑ Erickson, Edward J.: Ordered to Die. A History of the Ottoman Army in the First World War, Westport 2001, p. 19. See also: Hart, Peter: Gallipoli, Oxford 2011, pp. 1-5.; Beşikçi, Mehmet: The Ottoman Mobilization in the Balkan War. Failure and Reorganization, in: Boeckh, Katrin / Rutar, Sabine (eds.): The Wars of Yesterday. The Balkan Wars and the Emergence of Modern Military Conflict, 1912-13, Oxford 2018, pp. 163-4. The Ottoman-Italian (Tripolitanian) War of 1911, and the two Balkan Wars of 1912-13 each resulted in major Ottoman defeats.

- ↑ Erickson, Edward J.: Gallipoli. Command under Fire, New York 2015, pp. 22, 88, 94-95. Erickson notes the German-Ottoman cooperative mission had been in place since the 1880s, and all senior Ottoman officers were trained along German command and staff lines.

- ↑ General Staff Headquarters: The History of the Turkish Armed Forces, Ottoman Period. The Turkish War during the First World War. The Dardanelles Front Operations (April-May 1915), English Vol. 1 (Turkish Vol. V), Ipek Göldeli / Ela Gurdemir / Haluk Ertan (trans.), Ankara 1978, pp. 14-15.

- ↑ Gariepy, Patrick: Gardens of Hell. Battles of the Gallipoli Campaign Nebraska 2014, pp. 3-4; Erickson, Gallipoli, p. 33.

- ↑ Hart, Gallipoli, p. 34.

- ↑ Kaushik, Roy: Gallipoli and Salonika, in: Indian Army and the First World War, 1914-1918, Oxford Scholarship Online, 2018, p. 19.

- ↑ Erickson, Edward J.: Strength against Weakness. Ottoman military Effectiveness at Gallipoli, 1915, in: The Journal of Military History 65/4 (2001), pp. 986-7.

- ↑ General Staff Headquarters, History, pp. 31-32.

- ↑ Gariepy, Gardens of Hell, p. 25. Out of sixteen Entente capital ships, three were sunk, and three more were badly damaged by Ottoman minefields, and plunging shellfire from Ottoman mobile guns.

- ↑ General Staff Headquarters, History, p. 55.

- ↑ Bean, Charles E. W.: The Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918, Volume II – The Story of ANZAC from 4 May 1915 to the Evacuation of the Gallipoli Peninsula, Sydney 1941, pp. 195-199.

- ↑ Gariepy, Gardens of Hell, pp. 36-7.

- ↑ Major Halis: The Çanakkale [Gallipoli] Report of Major Halis. Selections from Major Halis, Istanbul 1975, p. 130; Erickson, Gallipoli, pp. 136-138.

- ↑ Hart, Gallipoli, pp. 221-2. By 5 May 1915, von Sanders had activated tactical group headquarters controlling each battle zone, and activated the XV Corps headquarters to control the Helles zone, allowing III Corps to focus solely on Anzac. Erickson, Gallipoli, p. 140.

- ↑ General Staff Headquarters, History, pp. 216-219.

- ↑ Bean, Official Histories, p. 438; General Staff Headquarters, History, pp. 229-230; Gariepy, Gardens of Hell, pp. 164-169.

- ↑ Haythornethwaite, Philip: Gallipoli 1915: Frontal Assault on Turkey, New York 2013, pp. 60-62.

- ↑ Karataş, Murat: The Gallipoli Campaign with Maps, Sydney 2007, p. 91.

- ↑ Erickson, Gallipoli, pp. 155-56.

- ↑ Karataş, Gallipoli, p. 150. The addition of Bulgaria to the Central Powers, and subsequent occupation of Serbia opened direct rail communications between the Germans and Ottomans. Besides fresh shipments of ammunition, shipments included 24cm Austrian mortars and 15cm howitzers, heavy weapons capable of destroying the flimsy Entente fortifications. See also: Haythornethwaite, Gallipoli, pp. 84-85; Erickson, Gallipoli, pp. 225-228.

- ↑ Kaushik, Gallipoli and Salonika, p. 17.

- ↑ Erickson, Strength, p. 1009.

- ↑ For a thorough historiographic analysis of literature on the Gallipoli campaign, see: Spiers, Edward: Gallipoli, in: The First World War and British Military History, Oxford 1991, pp. 165–188.

- ↑ Erickson, Strength, pp. 996-997.

- ↑ Uyar, Mesut: Remembering the Gallipoli Campaign. Turkish Official Military Historiography, War Memorials and Contested Ground, in: First World War Studies 7/2 (2016), p. 4. See also: Macleod, Jenny: Gallipoli. Great Battles, Oxford 2015, pp. 163-168.

- ↑ Turnaoğlu, Banu: The War of Independence (1919-1922). Road to the Independent Turkish Republic, in: The Formation of Turkish Republicanism, Princeton 2017, pp. 198, 218.

- ↑ Uyar, Remembering, pp. 5-6.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 8-9, 13.

- ↑ Bean, Official Histories, p. 910.

- ↑ Yilmaz, Ahenk: Memorialization on War-Broken Ground. Gallipoli War Cemeteries and Memorials Designed by Sir John James Burnet, in: Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 73/3 (2014), p. 333.

- ↑ Hughes, Matthew: The French Army at Gallipoli, The RUSI Journal 150/3 (2008), p. 64.

Selected Bibliography

- Bean, Charles E. W.: The official history of Australia in the war of 1914-1918. Volumes I and II, Sydney 1921-1924: Angus & Robertson Ltd

- Erickson, Edward J.: Gallipoli. The Ottoman Campaign, Barnsley 2010: Pen and Sword.

- Gariepy, Patrick: Gardens of Hell. Battles of the Gallipoli Campaign, Omaha 2014: University of Nebraska Press.

- General Staff Headquarters: The history of the Turkish Armed Forces Ottoman Period. The Turkish War during the First World War. The Dardanelles (Çanakkale) Front Operations (April-May 1915), volume 1, Ankara 1978: General Staff Publications.

- Karataş, Murat: The Gallipoli Campaign with maps. The Battles of Çanakkale with maps, Sydney 2007: Macquarie University.