Introduction↑

At the beginning of World War I, South East Europe (SEE) was comprised of patriarchal societies based on agrarian economies. In the Kingdom of Serbia in 1910, the rural population comprised 84.9 percent of the total population; approximately the same was true in Bulgaria and Romania. Women had no political or civil rights. Their role in society was limited to household and field work, giving birth, and raising children, with very few possibilities for more visible social engagement.

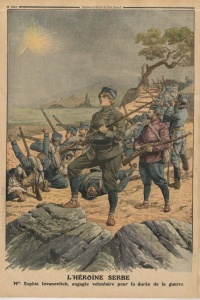

The wartime contributions of women in Serbia and other SEE countries included “purely male obligations” in the economy and public life: serving families and engaging in battle, both in the Serbian army and during the Toplica uprising. This topic remains largely unexplored in historiography; all studies to date have only been part of broader research. The first section of works could be categorized as popular history, followed by academic research on this important subject.

The war years forced women to engage in traditionally masculine activities and put on uniforms. Women became nurses and combatants. They lived in harsh conditions that required physical strength, energy, initiative, resourcefulness, leadership, and execution of orders. They demonstrated many capabilities that, according to the prevailing opinion, women lacked. It was believed that the ideal woman should be reliable, quiet, and gentle, with no ambition to engage in activities that involved responsibility and determination.[1]

Women’s Engagement at the Front↑

In the first phase of the war in Serbia (1914-1915), women were very much present in the war zone. This is understandable, given the nature and scope of military operations and suffering of the civilian population. In most cases, women involved in war efforts were doctors, nurses, and caregivers. Several women fought in the volunteer units of the Serbian army. The roles of doctors and nurses had already become associated with women due to their previous engagement in the wars: against Turkey (1876-1878), in Bulgaria (1885), and during the two Balkan wars (1912-1913). At the beginning of the First Balkan War, the female humanitarian society “Kolo srpskih sestara” gave to the “Ministarstvo vojno” a list of 1,500 military nurses from all social groups. This “female army” with twenty-five female doctors joined the medical corps of the Military Ministry immediately after mobilization in 1914, taking the place of paramedics who had gone to the battlefield. Among the women who nursed the wounded and sick was Helena, the daughter of King Peter I Karadjordjević (1844-1921).[2]

These twenty-five female doctors were positioned in military hospitals in the rear area, while the majority of their colleagues were stationed in field hospitals. Among these women doctors were Dr. Draginja Babić (1887-1915), who died in Valjevo hospital, Dr. Jelena-Jelka Popadić (1886-1920), Dr. Zorka Popović-Brkić (1873-1915), who died in Vrnjci, Dr. Zorka Jovanović (1886-1915), who died of typhus, and Dr. Božana Bartoš (1886-1946).[3] Many girls became nurses in training workshops for hospital staff. Trade schools in Serbia were turned into workshops where women and girls sewed clothes for soldiers, volunteers, the Red Cross, and National Defense.[4] Many prominent cultural figures became nurses, including the painter Nadežda Petrović (1873-1915), who died of typhus in Valjevo hospital. Physicians, nurses, and members of foreign medical missions provided help to the Serbian army in wartime, including those from Russia, Great Britain, and France, as well as from the United States, Greece, Switzerland, Italy, Denmark, and the Netherlands. Notable foreign missions were the British mission of Lady Louise Margaret Leila Wemyss Paget (1881-1958), the Russian mission of Countess Maria Konstantinova Trubeckaja (1864-1926), and the mission of Mrs. Anne Mabel St. Clair Stobart (1862-1954).[5]

In Montenegro women also assisted in transporting the wounded and nursed them in hospitals. During WWI the “Society for helping imprisoned Montenegrin soldiers”, as the branch of the Montenegrin Red Cross, was established in Paris. Milena, consort of King Nikola I of Montenegro (1847-1923) was a patron of the Society, while Ksenija Petrović-Njegoš (1881-1960) and Vjera Petrović-Njegoš (1887-1927), her daughters, led its administration.[6] According to traditional views, women did not belong on the battlefield. However, because many female fighters had taken part in the two Balkan wars (1912 and 1913), they expected to take part in the new war. Sofia Jovanović explained the motivation to participate in military operations:

Women served in volunteer corps involved in operations against the Austro-Hungarian army from August to December 1914: in the battles of Cer, Drina, and Kolubara, and during the withdrawal of the Serbian army in autumn 1915.[8] Milunka Savić, Antonia Javornik (Natalia Bjelajac) (1893-1974), Sofia Jovanović, and Živana Terzić (1888-?) took part in active combat. Milunka Savić offered herself as a volunteer to General Stepa Stepanović (1856-1929), but the commander of the Second Army sent her home. Then she went to Kragujevac, the headquarters of the Supreme Command. The girl did not accept the suggestion of Field Marshal Radomir Putnik (1847-1917), a Chief of Staff, to participate in the war effort as a nurse. Finally, Major Vojislav Tankosić (1881-1915) recruited her in the Rudnički volunteer unit where she served, armed and in uniform. She became the commander of the Assault Bomb Department. In the fighting on the Drina River Savić was awarded her first Karadjordje’s Star with Swords, and the Battle of Kolubara made her famous as a bombardier.[9]

The Slovenian Antonia Javornik came to visit her uncle, a Serbian army officer, just before the outbreak of the First Balkan War. When Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia, Antonia Javornik applied as a nurse and eventually became a soldier during clashes near Šabac in 1914. She successfully stopped the enemy's advance when she replaced the dead machine gunner she had been assisting. As a result, she earned a gold Obilić’s medal.[10] Sofia Jovanović fought in the Srem volunteer corps commanded by Ignjat Kirchner (1887-1944). As she was an experienced warrior from the Balkan wars, Kirchner entrusted her with the task of crossing on the left bank of the Sava with four men to raise the Serbian flag at the Austrian watchtower, cut the phone line, and pick up weapons. In autumn 1915, she fought in the defense of the Serbian capital.[11] Živana Terzić went to war to avenge the death of her brother who had been killed on Gučevo. In the night battle of Kurjačica, near the Drina River, she received the rank of sergeant.[12]

Vasilija Vukotić (1896-1977), the daughter of Serdar Janko Vukotić (1866-1927), fought in the Montenegrin army. She took part in the Battle of Mojkovac in early 1916.[13] A number of Montenegrin women also helped the army during this battle. The arrival of women on the battlefield meant not only the food and clothing supply, but it also had a powerful psychological effect on soldiers. Women believed that their contribution to warfare was not just taking over male jobs, but also helping their husbands, fathers, and brothers whenever they could.[14]

The Romanian peasant girl Ecaterina Teodoroiu (1894-1917) joined the Romanian army as a volunteer in October 1916. At first, she was a nurse. When her brother died, she became a soldier and fought bravely. She was captured but managed to escape. In November, Ecaterina Teodoroiu was wounded and hospitalized. Soon after, she came back to combat, received the rank of a second lieutenant, and took command of twenty-five soldiers. She died on 17 September 1917. She was awarded the medal for military virtue of the first class. Her life and heroic death on the battlefield became a part of Romania's national mythology.[15]

At the Salonika Front (1916-1918)↑

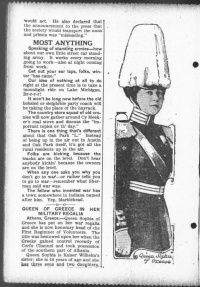

Five women fought in the Serbian army at the Salonika front. Milunka Savić (1888-1973), as a sergeant, gained another Karadjordje’s Star in the battle of Gorničevo. She was wounded nine times in combat. Consequently, she received two French Legions of Honor and the Miloš Obilić medal, one of the highest Serbian military decorations. Milunka Savić was the only woman awarded the French War Cross with Palm for her entire effort during World War I. She participated in the breakthrough of the Salonika front.[16] Also at the Salonika front, after the Serbian victory of Kajmakčalan and entering Bitola in the fall of 1916, Antonia Javornik received Karadjordje’s Star with Swords.[17] She was wounded in combat during the breakthrough of the Salonika front, and by the end of the war, she was a sergeant with twelve decorations.[18] Flora Sandes (1876-1956) was a nurse at the beginning of the war, and by the autumn of 1915, she became a fighter. Colonel Dimitrije Milić admitted her in the Second Infantry Regiment “Knez Mihailo”, also known as the Iron Regiment. Milić gave Flora a horse and orderly, the officers’ benefits.[19] Flora Sandes was wounded in the battle of Kajmakčalan.[20] In the hospital, the adjutant of Prince Alexander, later Alexander I, King of Yugoslavia (1888-1934) awarded her Karadjordje’s Star.[21]

Women’s Engagement in the Occupied Area↑

In the Toplica Uprising (24 February–22 March 1917), the only uprising in the occupied territories during World War I, women had an important role. Some of them helped the resistance movement (Četniks) before the outbreak of military revolt, supplying the fighters with food and clothing. Intelligence officers of the Austro-Hungarian Empire reported that women supported insurgents and their rear-service. Women, together with elderly men and children, carried ammunition, transported the wounded, kept watch, carried urgent letters, and brought water and food.[22]

Women had become members of resistance movements before the start of the uprising, but the majority of them joined insurgent troops during the war.[23] They played a large part in the attacks on the towns of Kuršumlija, Prokuplje, and Blace. Women and girls were fighting in the Ibar-Kopaonik, Central, and Jablanica units. Danica Dimić (?-1917), Stanka Petrović Dimić (?-1917), Nata Ognjanović (1899-?), and Veselinka Lukić fought under the command of Kosta Vojinović-Kosovac (1891-1917), one of the leaders of the uprising. The members of the Jablanica detachment were Milica Kujović, Jelena Šaulić (1896-1921), Milica Boračić and Danica Mrdelić. Rizna Radović (1891-1939) was in the Ibar-Kopaonik unit from January to early May 1917, and then she went into action in Bulgarian territory with the detachment of Kosta Pećanac (1879-1944). Rosa Pantić (1891-1945) was in the Central unit of Kosta Pećanac until 6 May and afterward joined Kosta Vojinović.

These women found themselves in guerilla detachments for various reasons.[24] Rosa Pantić joined her husband Vučko Pantić (1887-1945), a troop commander, after a punitive expedition had killed her child and burned down her house. Besides Rose Pantić, the wives of troop others commanders took part in combat. Rizna Radović and Veselinka Lukić joined the Četniks before the uprising due to the brutality of the Bulgarian occupation authorities. The majority of women warriors were killed in the uprising. Some women survived: Rizna Radović was wounded and her right leg was amputated, and Veselinka Lukić awaited the end of the war in the Shumen prisoner camp in Bulgaria. Rosa Pantić also survived World War I.[25] In Montenegro, the “Komit” guerrilla movement was strong throughout occupation, and a number of women joined the revolt. Milosava Perunović (1899-1945) went to war in the spring of 1916 and remained among the Četniks until the end of the war.[26]

Women in the Rear Area: The Burden of the War (1914-1915)↑

In the Serbian rear area, women became engaged in the business on a large scale. Serbian society was predominantly agrarian with small farmers; during the war, rural women took on the tasks previously performed by the now-conscripted men, in addition to their normal home and child-care responsibilities. These new tasks included the most difficult physical labor. During the defense of Serbia, mothers, sisters, and wives also went to visit the troops. The testimonies from that time describe typical war scenes on roads in Serbia during 1914 and 1915: women laden with heavy canvas bags traveled dozens of kilometers on foot in order to see their sons, brothers, and husbands, bringing them food and retraining. It was often their last brief meeting.[27]

During the two first years of the war, Serbian women experienced refuge and exile, deprivation, and withdrawal with the army, including the retreat through Albania in cold weather and snow at the end of 1915.[28] In Montenegro, as in Serbia, women carried the heavy burden of the war. Making money and household issues became women's responsibilities.[29] Muslim women represented a part of Serbian and Montenegrin female population. Like Serbian and Montenegrin women, Muslim women felt the weight of life in wartime, lacking basic necessities (food, clothing, and shoes). They, however, were treated differently by the occupying powers. In fact, in three southern districts of Serbia, the troops of Central Powers were greeted as liberators. Consequently, Muslim women were spared from various penalties and tortures that Orthodox women experienced.[30]

In Bulgaria, the women were not in the immediate area of the front. They had a different experience of the war; because combat operations were conducted in foreign territory, women were spared the brutality of the occupation administration. Bulgarian woman were the Samaritans - volunteer nurses in the war. Eleanore, Queen, consort of King Ferdinand I, King of Bulgaria (1860-1917) was also a Samaritan who supported the organization financially.[31] Like women in Serbia and Montenegro during the war, Bulgarian women exerted greater work effort than in peacetime. Due to mobilization of men, they had to take on the burden of family support and economic activity, working primarily in agriculture but also in other sectors. They struggled with famine, fuel shortages, and clothing shortages, as well as rising inflation and high cost of living. During the spring of 1918, famine and other social factors caused mass protests by women in Bulgarian towns (“Woman uprising”).[32]

Occupied Serbia as a Country of Women, Children, and the Elderly (1915-1918)↑

Due to the greater number of women than men, Serbian society during the occupation in World War I can be described as a female society. According to the Serbian census in 1910, there were 100 females per 107 males. By the time of the Austro-Hungarian census in 1916, there were 100 females per sixty-nine males. The missing men were in the prime of their lives. They were killed in combat, involved in warfare, or interned. It all resulted in unnatural and unusual life conditions. Young and middle-aged women, biologically destined for motherhood, could not find similar-age partners.[33]

In this female society, the predominant feelings were sadness, anxiety, and fear. Although feelings of love were psychologically suppressed, they were nevertheless present.[34] During the war, there were very few marriages, in part because of the disproportion between the number of men and women, but, above all, because of the poor economic situation and poverty. In the first three months of 1916, according to statistics from Austro-Hungarian authorities, only eighty-five couples were married in Belgrade.[35] Reasons for marriage were largely pragmatic: to survive and to feed oneself. Still, there were some love marriages. Even in times of peace, not many marriages were based on love, especially in rich bourgeoisie or peasant families. Furthermore, as moral norms were relativized during the war, more illegitimate children were born than during peacetime. Before the war, illegitimate children had comprised only 1 percent of the total number of newborns, while during the occupation, 4 percent of the children were born out of wedlock.[36]

Historical sources provide contradictory data about the private lives of women during the occupation. Sources of Serbian origin emphasize a lifestyle absent of sin; loyalty to children and fidelity to husbands, even those who were deceased. In fact, they claimed that widows especially remained faithful to the memory of their husbands. German and Austro-Hungarian sources present a different picture. One could live comfortably and “fully” just with enough money, but when it was gone, the company of members of the occupying powers offered a “rescue.” Thus, the phenomenon of prostitution was registered in Belgrade in 1916. There were about 300 prostitutes in five brothels. It was not only the pre-war prostitutes who were employed in the “oldest profession” but also women from rich and respectable families. Some women had relations with the Austro-Hungarian officers and officials, mostly those of South Slavic origin. The reality was somewhere in between Serbian and Austro-Hungarian data.[37]

In war-affected families, children were the main victims. They matured earlier and were burdened with many obligations that had been the responsibility of adult males during peacetime. They endured the same hardships as adults and suffered the deteriorated living conditions. The youngest members of the family frequently fell ill, starved, and had no adequate clothing or footwear. While taking refuge, children experienced trauma with lasting effects. For several years, they were separated from their fathers, without their love and care. Some children were wounded or killed in combat. Young children and teenagers were also among civilian and military internees and they were one of the largest groups of victims of famine and epidemics. Children died of smallpox and the infant mortality rate was very high.[38] The physician Slavka Mihajlović has noted:

The occupying authorities directed their main effort toward encouraging faster development of agriculture, in addition to the development of some crafts and refurbishing of food processing factories and plants. The occupying authorities used all available labor: women, children, elderly men, prisoners of war, and internees.[40] Women performed all field tasks, even though they had young children. On early evenings, they went to do housework and settle cattle. The help from elderly men and male children was often insufficient. Women from poor families with many children were in the worst situation. A contemporary described obligations and duties of peasant women:

They plowed, planted, harvested, stacked hay, worked from morning until night, often encouraged by a bayonet and rifle butt, just to increase yields to enemies. Women bred livestock, concealed and struggled, and often lost their lives in an attempt to collect and protect their property. They were toiling, pulling stones and loaded bags, doing hard labor, without any recognition of the crude enemy. Besides, they were paying taxes and war loans and feeding soldiers in their villages.[41] Women were also forced to take on the “social” responsibilities of men. Besides traditional mother-housewife roles, women stood for their families. It meant, among other things, managing many new obligations (i.e. taxes, surtaxes, and war loans).[42]

Changed conditions erased the line between fighting and home front, between war and peace, between public and private life. The female struggle to survive and watch over the family, work in the household and in the field, cannot be seen in isolation from what their men in uniform were doing on the frontlines. In fact, their efforts were directed toward helping those at the front. In some way, each activity was focused on the war effort - in addition the task of basic survival. In wartime, corn bread with plum jam was all a family needed for a festive cake. The lack of basic foods and extreme expense frightened everyone: “How we shall live hard, how to provide - there is nothing.”[43] Sowing and harvesting - without sufficient male labor, tools, and animals - felt like more of a success than it would have under normal circumstances.

Women as Victims of War↑

During the war and occupation of 1914-1918, Serbian women were victims of diverse and atrocious forms of persecution - sexual violence, beatings, and forced displacement. They were forced to take part in the pursuit of compatriots. Some of them were taken to Austro-Hungarian and Bulgarian internment camps. They were also looted, arrested, and exposed to various humiliations and psychological torture.[44]

Women were victims of punitive expeditions of the Central Powers. The first such expedition came to Mačva and the Sava Valley at the start of the war, in the summer of 1914. After suffering a defeat, troops of the Dual Monarchy committed atrocious crimes against civilians of both sexes and various ages. The rural population was subjected to mass killings and internment. Two censuses (1910 Serbian census and 1916 Austro-Hungarian census) showed decline of the female population by 14.36 percent.[45] The second punitive expedition was active in Toplica and Jablanica upon the termination of the Toplica uprising in the spring of 1917. According to the report of the International Commission for the investigation of war crimes, Bulgarians killed 20,000 people during World War I.[46] Data from partial surveys show that 452 women were killed in 129 villages, 829 women were beaten, some of whom received more than 100 strikes.[47] Only 163 cases of women raped by Bulgarian committees and soldiers were recorded. Due to shame and fear, rape was a terrible secret for most victims.[48]

The decline in the female population during World War I was significant. The Military-General Government determined that in 1916 there were 40,000 fewer women than in 1910.[49] This figure includes also women who had died before the start of World War I. During the war, women died from diseases, old age, malnutrition, and effects of occupation in general. Some were killed in combat or sentenced to death. Data on losses are incomplete, so it is impossible to determine the exact number of casualties.

Women suffered “extended” consequences of traumatic war events. Some gave birth to children conceived in rape. These unwanted children were given the nickname “bugarčići” (little Bulgarians) and were marked for life. Mothers were torn between love and affection for the child and the memories of survived violence. Women who collaborated with the occupation authorities suffered at the hands of their compatriots. Some were punished by receiving a haircut. Mistresses of enemies were particularly hated and scorned.[50]

Montenegrin women were victims of war, too. It was noted that they were among internees in Austro-Hungarian internment camps, mostly those in Frauenkirchen (Boldogasszony) and Karlstein. The first women who were interned were the two daughters of General Vešović. In March 1918, increased activities of the guerrilla movement resulted in the internment of many people, including 200 women and children.[51]

Conclusion↑

After World War I, women were able to work to improve their status in a patriarchal society. Women’s roles in the war and their war experience contributed to an increased tendency toward changes as an “exit” from the patriarchal model of behavior. In cities, women began to pursue education and employment. Regardless of their suffering, burdens, and efforts in the war, which lasted more than four years, women in Serbia, the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenians and the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, did not get civil rights. Females only gained political rights and the right to economic independence and work after World War II. The Law on Marriage and Family Relations repealed Serbian 19th-century legislation, and women gained legally equal status. Female residents of neighboring countries had a similar fate. In Bulgaria, women gained the right to vote in 1944 and in Greece in 1952.

Božica Mladenović, University of Niš

Section Editors: Milan Ristović; Tamara Scheer; Richard C. Hall

Notes

- ↑ Krippner, Monica: Žene u ratu, Srbija 1915-1918 [Women in the War, Serbia 1915-1918], Belgrade 1986, p.17.

- ↑ Srpkinje u službi otadžbini i narodu za vreme balkanskih ratova 1912. i 1913. godine kao i za vreme svetskog rata 1914-1920 [Serbian Women in the Service of the Homeland during the Balkan Wars 1912 and 1913 and World War I 1914-1920], Belgrade 1933, pp. 8-9.

- ↑ Gavrilović, Vera: Žene lekari u ratovima 1876-1945. Na tlu Jugoslavije [Female Doctors in Wars 1876-1945 on the Territory of Yugoslavia], Belgrade 1976, p. 10.

- ↑ Srpkinje u službi otadžbini [Serbian Women in the Service of the Homeland] 1933, p. 12.

- ↑ Krippner, Žene u ratu [Women in the War] 1986, p. 32-167; Mitrović, Andrej: Srbija u Prvom svetskom ratu [Serbia's Great War], Belgrade 1984, pp. 191-194.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 335.

- ↑ Đurić, Antonije: Žene-Solunci govore [The Solunci Women Speak], Belgrade 1987, p. 137.

- ↑ Naše patnje i naše borbe [Our sufferings and our struggles], Geneva 1918, p. 57.

- ↑ Đurić, Žene-Solunci govore [The Solunci Women Speak] 1987, pp. 35-42.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 28-29.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 139-140.

- ↑ Mladenović, Božica: Živana Terzić – ratnica sa Drine [Živana Terzić – the Woman Warrior from the Drina], in: Istorijski časopis 49 (2002), pp. 275-278.

- ↑ Đurić, Žene-Solunci govore 1987, pp. 45-81.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 423.

- ↑ Bucur, Maria: Between the Mother of the Wounded and the Virgin of Jin: Romanian Women and the Gender of Heroism during the Great War, in: Journal of Women’s History 12/2 (2000), pp. 30-56.

- ↑ Đurić, Žene-Solunci govore 1987, pp. 35-42.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 28-29.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 27, 30.

- ↑ Krippner, Žene u ratu [Women in the War] 1986, p. 157.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 205.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 206.

- ↑ Mladenović, Božica: Žena u Topličkom ustanku 1917. godine [Women in the Toplica Uprising], Belgrade 1996, p. 29.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 45.

- ↑ The details can be found in the correspondence and diaries, primary sources held in the Military Archive in Belgrade.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 133-134. On Rosa Pantić, see Mladenović, Božica: Sudbina žene u ratu: Rosa Pantić (1891-1945), Belgrade 2012.

- ↑ Ibid., pp.101-132.

- ↑ Mladenović, Božica: Porodica u Srbiji u Prvom svetskom ratu [The Family in Serbia in the First World War], Belgrade 2006, p. 97.

- ↑ Ibid., p.183.

- ↑ Rakočević, Novica: Crna Gora u Prvom svjetskom ratu [Montenegro in the First World War 1914-1918], Cetinje 1969, pp. 327-328.

- ↑ Mladenović, Božica: Grad u austrougarskoj okupacionoj zoni u Srbiji od 1916. do 1918. godine [The town in the Austro-Hungarian Occupation Zone in Serbia from 1916 to 1918], Belgrade 2000. Data showing privileged status of Muslim population can be found in several sources.

- ↑ Zlateva, Ani: Tsaritsa Eleonora – Koronovaniyat angel na Bŭlgariya [Queen Eleonora - crowned angel of Bulgaria], in: Nauchna konferentsiya, posvetena na prinosa na Tsar Ferdinand za izgrazhdaneto na voennite memoriali ot Rusko-turskata osvoboditelna voĭna [Scientific conference dedicated to the contributions of King Ferdinand to build a war memorials of the Russo-Turkish War], Pleven, issued by H.M. King Simeon II, online: http://www.kingsimeon.bg/archive/viewcategory/id/163 (retrieved: 1 October 2011).

- ↑ Crampton, Richard J.: A Concise History of Bulgaria, Cambridge 1997, pp. 143-145; p. 216.

- ↑ Mladenović, Božica: Rat i privatnost: Prvi svetski rat [War and Privacy. The World War I], in: Ristović, Milan (ed.): Privatni život kod Srba u dvadesetom veku [Private Life of the Serbs in 20th century], Belgrade 2007, pp. 777-795.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 772.

- ↑ Archive of Serbia (Fond Vojno-generalni guvernman), XIV/60.

- ↑ Mladenović, Rat i privatnost [War and Privacy] 2007, p. 775.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 772. For more on this subject see: Knežević, Jovana: Prostitutes as a Threat to National Honor in Habsburg-Occupied Serbia during the Great War, in: Journal of the History of Sexuality 20/2 (2011), pp. 312-335.

- ↑ Mladenović, Grad u austrougarskoj okupacionoj zoni u Srbiji [The town in the Austro-Hungarian Occupation Zone in Serbia from 1916 to 1918] 2000, p.174.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 169.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 108.

- ↑ Pravda, 11. Oktobar 1919, p. 1.

- ↑ Mladenović, Rat i privatnost [War and Privacy] 2007, pp. 783-784.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 790.

- ↑ Mladenović, Porodica u ratu [The Family in Serbia in the First World War] 2006, p. 183.

- ↑ Mitrović, Andrej: Šabac pod okupacijom [Šabac under the Occupation], in: Filipović, Stanoje (ed.): Šabac u prošlosti [Šabac in the Past], volume iv, Šabac 1984, p. 125.

- ↑ Documents relatifs aux violations des conventions de la Haye et du Droit international en general commisses de 1915-1918. Par les Bulgares en Serbie ocupee, Paris 1919; Rapport de la Commission interalliée sur les violations des Conventions de la Haye et de Droit International en general, commisses de 1915-1918. Par les Bulgares en Serbie occupee, Paris 1919.

- ↑ Mladenović, Žena u ustanku [Woman in the Toplica Uprising] 1996, pp.91-96.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 142-143.

- ↑ Mladenović, Grad u austrougarskoj okupacionoj zoni u Srbiji [The town in the Austro-Hungarian Occupation Zone in Serbia from 1916 to 1918] 2000, p. 28.

- ↑ Mladenović, Žena u ustanku [Woman in the Toplica Uprising] 1996, pp. 73-79.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 327-328.

Selected Bibliography

- Anonymous: Naše patnje i naše borbe (Our sufferings and our struggles), Geneva 1917: Štamp. 'Ujedinjenja'.

- Rapport de la Commission interalliée sur les violations des conventions de la Haye, et le droit international en général, commises de 1915-1918 par les Bulgares en Serbie occupée. Documents, volume 2, Paris 1919: Imprimerie Yugoslavia, 1919.

- Bucur-Deckard, Maria: Between the mother of the wounded and the virgin of Jin. Romanian women and the gender of heroism during the Great War, in: Journal of Women's History 12/2, 2000, pp. 30-56.

- Commission interalliée sur les violations des conventions de la Haye (ed.): Documents relatifs aux violatins des conventions de la Haye. Et du droit international en général, commises de 1915-1918 par les Bulgares en Serbie occupée, Paris 1919: Imprimerie Yugoslavia.

- Commission interalliée sur les violations des conventions de la Haye, et du droit international en général, commises de 1915-1918 par les Bulgares en Serbie occupée (ed.): Rapport de la Commission interalliée sur les violations des conventions de La Haye et du droit international en général, commises de 1915-1918 par les Bulgares en Serbie occupée, Paris 1919: Imprimerie Yugoslavia.

- Crampton, Richard J.: A concise history of Bulgaria, Cambridge 1997: Cambridge University Press.

- Gavrilović, Vera: Zene lekari u ratovima 1876-1945. na tlu Jugoslavije (Female doctors in wars 1876-1945 in the territory of Yugoslavia), Belgrade 1976: Nauc̆no drus̆tvo za istoriju zdravstvene kulture Jugoslavije.

- Knežević, Jovana Lazić: Prostitutes as a threat to national honor in Habsburg-occupied Serbia during the Great War, in: Journal of the History of Sexuality 20/2, 2011, pp. 312-335.

- Krippner, Monica: Žene u ratu. Srbija 1915-1918 (Women in the war. Serbia 1915-1918), Belgrade 1986: Naroda knjiga.

- Mitrović, Andrej: Srbija u Prvom svetskom ratu (Serbia in World War I), Belgrade 2004: Stubovi Kulture.

- Mitrović, Andrej: Srbija u Prvom svetskom ratu (Serbia's Great War), Belgrade 1984: Srpska književna zadruga.

- Mitrović, Andrej: Šabac pod okupacijom (Šabac under the Occupation), in: Filipović, Stanoje R. (ed.): Šabac u prošlosti (Šabac in the Past), volume IV, Šabac 1984: Istorijski arhiv, pp. 99-214.

- Mladenović, Božica: Žena u Topličkom ustanku 1917 (Women in the Toplica Uprising), Belgrade 1996: Socijalna Misao.

- Mladenović, Božica: Sudbina žene u ratu. Rosa Pantić (1891-1945) (Destiny of a woman in a war. Rosa Pantić (1891-1945)), Belgrade 2012.

- Mladenović, Božica: Grad u austrougarskoj okupacionoj zoni u Srbiji od 1916. do 1918. godine (The cities in Austro-Hungarian occupation zone in Serbia 1916-1918), Belgrade 2000: Čigoja štampa.

- Mladenović, Božica: Rat i privatnost. Prvi svetski rat (War and privacy. The First World War), in: Ristović, Milan (ed.): Privatni život kod Srba u dvadesetom veku veku (Private life of the Serbs in the 20th century), Belgrade 2007: Clio, pp. 777-795.

- Mladenović, Božica, Istorijski institut u Beogradu (ed.): Živana Terzić – ratnica sa Drine (Živana Terzić – the Woman Warrior from the Drina), in: Istorijski časopis 49, 2002, pp. 275-278.

- Mladenović, Božica / Živković, Tibor: Porodica u Srbiji u Prvom svetskom ratu (The family in Serbia in the First World War), Belgrade 2006: Istorijski Institut.

- Pavlović, Živko (ed.): Srpkinje u službi otadžbini i narodu za vreme balkanskih ratova 1912. i 1913. godine kao i za vreme svetskog rata 1914-1920 (Serbian Women in the service of the homeland during the Balkan Wars 1912 and 1913 and World War I 1914-1920), Belgrade 1933.

- Rakočevic, Novica: Crna Gora u prvom svjetskom ratu 1914-1918 (Montenegro in the First World War 1914-1918), Cetinje 1969: Istorijski Institut Titograd.

- Subotić, Vojislav M. (ed.): Pomenik poginulih i pomrlih lekara i medicinara u Ratovima, 1912-1918, redovnih, dopisnih i počasnih članova, osnivača, dobrotvora i zadužbinar, 1872-1922 (The memorial of killed and death doctors and medical workers during the wars 1912-1918), Belgrade 1922: Vreme.

- Đurić, Antonije: Žene-Solunci govore (Solunci women speak), Belgrade 1987: NIRO 'Književne novine'.

- Zlateva, Ani: Tsaritsa Eleonora - Koronovaniyat angel na Bŭlgariya (Queen Eleonora - crowned angel of Bulgaria), in: Nauchna konferentsiya, posvetena na prinosa na Tsar Ferdinand za izgrazhdaneto na voennite memoriali ot Rusko-turskata osvoboditelna voĭna (Scientific conference dedicated to the contributions of King Ferdinand to build a war memorial of the Russo-Turkish War), 2011.