Introduction↑

Montenegro faced World War I militarily exhausted, economically worn out, and with a multitude of political, economic and social issues. The unfavorable climate in the country was further aggravated by a decline in the country’s international reputation due to events that took place during the First Balkan War, specifically the vast number of casualties and significant material damage caused in the Siege of Scutari, but also by the unresolved issue of its union with Serbia. Although an analysis of the events that took place during the First World War covers a well-known period of time, the political and military activities of the country in the period leading up to the capitulation of the Montenegrin army were significantly different in nature and importance, with the King and the government leaving the country in 1916 and carrying out their exclusively diplomatic activities under the new circumstances that the exile status implied.

The Political Situation before the war and Plans for Rearranging the Balkans↑

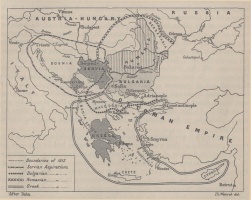

Understanding the political position of Montenegro at the beginning of the First World War means not only analyzing the internal state of affairs in the country, but also the “international climate” formed after the Bucharest Peace Treaty in 1913. The future of the Montenegrin state was jeopardized by the unresolved issue of its union with Serbia, which the Montenegrin people welcomed, as well as by the plans for restructuring relations in the Balkans devised by the Central Powers.

The elements of this restructuring were discussed in early March 1914, at a meeting between, Wilhelm II, German Emperor (1859-1941), Francis Joseph I, Emperor of Austria (1830-1916), Count Leopold Berchtold (1863-1942), the Austrian Minister of Foreign Affairs, and Count István Tisza (1861-1918), the Hungarian Prime Minister. They focused mainly on “a prepared union between Serbia and Montenegro”. The conclusion that they reached was that the union between the two countries must be prevented, using diplomatic means or even violence if necessary.[1] If it proved impossible, Montenegro should be divided into two parts and merge its coastline with Albania, while the rest, the larger portion, would join Serbia. The determination to treat Montenegro as such was also confirmed during a subsequent discussion of the political situation in the Balkans at a meeting between the German Emperor and the Austro-Hungarian heir to the throne, Franz Ferdinand, Archduke of Austria-Este (1863-1914), which took place on 27 March 1914. The given tasks were to be accomplished diplomatically. When completed, Austria-Hungary and Germany would have achieved political prestige in the Balkans, thus eliminating Russian influence.[2]

The plan for a “peaceful conquest” of the Balkans illustrated the aims of the Central Powers. It was ultimately unrealistic since it implied that large political changes could be achieved in a non-violent way—with the rise of Bulgaria, weakening of Serbia, gaining of Romanian support, and the creation of a new Balkan alliance against Russia and the Entente. The subsequent course of events resulted in the planned political changes not coming to fruition as was envisaged. Even after the Sarajevo assassination, the basic ideas to alter political relations in south-eastern Europe were still not abandoned. The determination to change the resulting situation was confirmed in a letter from German Emperor Wilhelm dated 4 July 1914.[3]

Montenegrin policy during the July Crisis in 1914↑

During the crisis caused by the Sarajevo assassination, the question of Montenegro was not directly raised. A more solid political and military affiliation between Serbia and Montenegro did not suit the plans of the Central Powers. Political contacts between Montenegro and the Triple Alliance during the war were colored by an effort to prevent such relations between Serbia and Montenegro which could jeopardize the political subjectivity of Montenegro. The aim was to strengthen a co-alliance of countries hostile towards the Triple Entente.

The ambitions of Nikola I, King of Montenegro (1841-1921) to ensure his dynasty’s position with subjectivity and territorial expansion coincided, to some extent, with the efforts of the Central Powers to win Montenegro over to their side. This caused wavering regarding the political position of the country in official Montenegrin circles before the beginning of the war. The idea of Montenegrin neutrality was present for quite some time during the political crisis following the Sarajevo assassination. Non-participation in the war could have strengthened the impaired foreign and internal stability of the country. Aleksandar Aleksandrovič Girs,[4] Russian emissary in Cetinje, notified Minister Sergei Dmitrievich Sazonov (1860-1927) on 18 July 1914 (31 July 1914), that the King addressed the issue of Montenegrin interference in the war activities stating that Montenegrins would not attack unless the Austrians stepped onto Montenegrin territory first.[5]

Negotiations regarding Montenegrin neutrality were conducted between Baron Eduard Otto (1860-1936),[6] the Austro-Hungarian representative in Cetinje, and Petar Plamenac (1872-1954), Montenegrin Minister of Foreign Affairs. Austria-Hungary offered financial support to Montenegro and territorial compensation in exchange for not entering the war on the side of Serbia and Russia.[7] After one of those talks, Baron Otto informed Vienna that if Montenegro were promised a border along the river Bojana, or even Drim, Austria-Hungary could count on Montenegro as its partner.[8]

Negotiations with the diplomatic representative of Austria-Hungary continued even after his government gave Serbia an ultimatum, and ran simultaneously with Montenegrin military preparations to provide Serbia with military assistance; no results were achieved until 5 August 1914, when Baron Otto left Cetinje. Apart from having Russia, its traditional patron, enter the war, Montenegro was forced to remain officially in the same alliance by the determination of its people to provide brotherly help to Serbia. The decision of the National Assembly from 1 August 1914 for Montenegro to join the war and selflessly support Serbia and Russia was another expression of such sentiment.

Political and Military Circumstances at the Beginning of the War↑

The outbreak of war further aggravated problems which existed between Cetinje and Belgrade. Serbia acquired a more significant role due to its size and military forces. According to the joint operation plan of the Serbian and Montenegrin armies in the war against Austria-Hungary, devised by Field Marshal Radomir Putnik (1847-1917), Chief of Headquarters of the Serbian High Command, two-thirds of the Montenegrin army was placed under the supreme command of Serbia on 6 August 1914. Delegates were exchanged in order to ensure stable communication between the Serbian and Montenegrin armies.[9] The Montenegrin Supreme Command designated Brigadier Jovo Bećir (1870-1942) as the delegate in the Headquarters of the Serbian army. However, he resigned from this duty, voicing his protest against the unionist movement among Serbian officers, and insistence on an unconditional merger of Montenegro and Serbia.[10]

Upon his arrival to Montenegro, General Božidar Janković (1849-1920) was appointed Chief of Headquarters of the one third of the Montenegrin army designated to defend Montenegrin territory. Although King Nikola held the supreme command, the entire armed forces of the country were essentially under the command of Serbian officers. Occurrences during the war pushed Montenegro to the margins of Serbian and south-Slavic political events.

The outbreak of the First World War accelerated the processes which had already begun. However, the creation of the historical conditions for a union of the two countries through resolving the Yugoslav question, though it had been the main Montenegrin foreign political goal for long time (provided it was accomplished under its dynasty), was now not welcomed by Montenegrin officials. The integration process now posed a threat to Montenegro’s sovereignty and to the fate of the dynasty.

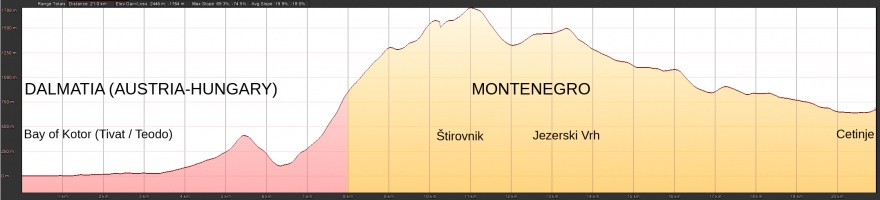

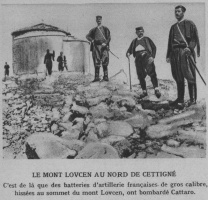

In the first days of war, there were misunderstandings concerning the position of the units of the Montenegrin army within the realization of the joint war plan. The majority of the Montenegrin army was located at the Herzegovina front and at Mount Lovćen, while only one-fifth of it was located in the region of Pljevlje in cooperation with the Serbian army. This reflected the tendency of the Montenegrin court towards independent operations “at a time when the main collision between Serbian and Austro-Hungarian armies was yet to happen”.[11]

The visible separation of Montenegro from its commitments as an ally, expressed through diplomatic activities seeking to ensure political support for the concept of preserving Montenegro as an independent state, was aimed at both the Central Powers and the Allied countries. Out of the complex diplomatic activities, several missions should be singled out: General Mitar Martinović’s (1870-1954) mission to Russia; Andrija Radović’s (1872-1947) mission to France; talks between representatives of Montenegro and Serbia in Cetinje; the retreat of the Serbian army; further political steps of Montenegro; and the actions taken by its armed forces.

The mission of General Mitar Martinović (April to November 1915) is associated with Montenegro’s attempt to appoint a minister in Russia. The King succeeded in appointing a Montenegrin military delegate with the Russian Supreme Command to acquire money, food and military supplies for Montenegro. The task of Martinović’s mission also concerned the Russian position towards a territorial expansion of Montenegro. Martinović wrote that in late March 1915, the King summoned him to the court and told him of a letter that was received from the Nikolai Nikolaevich, Grand Duke of Russia (1856-1929) stating that, due to major Russian victories and the descent of the Russian army into the Hungarian plains, Austria had sent peace proposals. The Grand Duke requested that a trusted individual be sent to explain all of the King’s wishes “regarding the future Montenegrin borders”. The King proposed that Montenegro ask Bosnia for Sarajevo with the surrounding area and all of Herzegovina, and ask Dalmatia for Split and the entire coastline from Split all the way south to the Montenegrin coastline.[12]

An agreement on borders implied that the issue of the future state and legal status of Montenegro had already been favorably resolved, and the call to unite these countries into one was not given much importance. Even Milica Nicholayevna, Grand Duchess of Russia (1866-1951) put before Nicholas II, Emperor of Russia (1868-1918) the question of Montenegrin borders in a somewhat more modest form.[13] In official Russian circles, such Montenegrin claims were deemed to be contrary to Russia’s policy towards Montenegro. They also warned that this would separate Montenegrin from Serbian interests. They were not welcomed at the Russian court since they had an almost identical aim as the previously conducted negotiations with Austria-Hungary and Germany.

Providing food for the people and army was a problem for the Montenegrin government from the beginning of the war. There was also a shortage of arms and military equipment. Montenegro had run out of war supplies and almost entirely depended on external aid.[14] According to an agreement between Russia, France and England, Montenegro was given a loan of 10 million francs for arms and other equipment. That was the first major financial aid approved for Montenegro since the beginning of the war. Previously, in October 1914, it received an advance of 500,000 francs for leaving Scutari as a portion of the promised international loan.[15]

At the beginning of the war, Serbia provided the Montenegrin army with weekly payments of 500,000 dinars so it could sustain itself. The Allies put Serbia in charge of controlling the amount of financial resources spent by the Montenegrin government. When, following the mission of Evgenije Popović (1842-1931), the British, French and Russian governments agreed to grant Montenegro a loan in the amount of 10 million francs, provided by the three allies in equal portions, it was decided that the King would be given smaller amounts in successive installments, as desired by the Serbian government. The loan was primarily meant to meet the military needs of Montenegro for purchasing military supplies and equipment in France.

A condition for the loan was for the military supplies to be obtained according to the instructions of the Montenegrin Supreme Command led by Serbian officers. This was aimed at preventing King Nikola from undertaking independent military or political actions.[16] Such conditions for approving the loan were seen as proof that Serbia was favored by the Allies and of the unequal treatment that Montenegro received.

The Offensive of the Austro-Hungarian Army in October 1915 and its Impact on Montenegro↑

The beginning of the great Austro-Hungarian offensive against Serbia on 6 October 1915 changed the agenda of the next talks between representatives of the two countries. The talks took place again after the retreat of the Serbian army through Montenegro and Albania to the Albanian coast. The contacts between representatives of the two countries, made after the Serbian Supreme Command took over Scutari, and later upon the arrival of Prime Minister Nikola Pašić (1845-1926) at Cetinje on 22 December 1915, concerned the continued allied path of the two countries. According to literary sources, Prime Minister Pašić advised King Nikola that he should assume the position held by the Serbian government, that if the situation required, the Montenegrin army would retreat together with the Serbian army.[17]

The position of Serbia regarding Montenegro’s military strategy moving forward - to negotiate for peace or retreat with the Serbian army - became an issue due to different interpretations of the contents of a report filed by the Serbian Military Delegate, Colonel Petar Pešić (1871-1944), to King Nikola on 1 January 1916. Upon its arrival to Corfu and even afterwards, the Serbian army sought to prove that peace negotiations between Montenegro and Austria-Hungary did not take place at the suggestion of its delegate. After witnessing chaos in the army, Colonel Pešić actually suggested urgent peace negotiations in his report to King Nikola, since the situation required a quick solution and not procrastination.[18] However, regardless of the Serbian position on peace negotiations, the extent to which it could have affected Montenegro’s decision on the matter is arguable. Considering the Montenegrin peace negotiations with Austria-Hungary in late 1915, the fall of the Serbian military, and King Nikola’s belief that he could make peace when he wanted, it is possible that after the Serbian demise, Montenegrin officials moved forward with their own plans. They may have sought to use peace negotiations to withdraw from the war and realize the idea of creating a Greater Montenegro, or “a great Serbian empire under the Petrović dynasty”. Having the Montenegrin army retreat with the Serbian army was not a favorable solution because of the risk of being merged with the Serbian army and the subsequent expansion of the unionist movement. The aftermath of the Austro-Hungarian offensive in November 1915 changed the conditions for political and military actions of both countries, particularly for Montenegro after the capitulation of its army.

By the time that it withdrew from the war in January 1916, considering the exhaustion from previous wars and the small amount of arms, materials, and technical supplies that it possessed, the Montenegrin army had successfully managed all of the tasks it had been given, even those that “exceeded its tactical and operational capabilities”.[19] The role of the Montenegrin army was particularly important during Mackenzie’s offensive against Serbia in October 1915. Apart from assisting the majority of Serbian forces “to withdraw to the region of Kosovo Polje and Metohija before the Austro-Hungarian attack”, its involvement was also significant when the army had to retreat from Kosovo before the offensive of the Bulgarian army. A portion of the Serbian army was forced to retreat to Scutari and the Albanian coast through Montenegro. By playing the role of a general strategic protector, the Montenegrin army assisted the Serbian army in its retreat despite suffering substantial losses itself.

After the retreat of the Serbian army, the only favorable solution for Montenegro was to withdraw its army from the country, but this did not happen. The explanation for this can be found in the lack of a clear plan and execution by the primary government institutions, mainly the King and the government, in the conflict between the growing idea of a union of south Slavic peoples and the narrow dynastic interests of governing circles. The way in which the Montenegrin army was organized and commanded also played a significant role along with the distrust within dynasty and political maneuvering of royalist circles in both Belgrade and Cetinje. The Allies also played a part, failing to promptly react to the crisis that the Montenegrin army found itself in. In addition to the Allies receiving generally poor advice about Montenegro, the news that it was negotiating for peace with Austria-Hungary separately had a somewhat negative effect, especially after the Montenegrin army entered Scutari in 1915. Thus, the Montenegrin army left the continuity of the Allied armies in early 1916 which had a significant impact on the final destiny of the state of Montenegro.

Negotiation of Armistice and a Separate Peace Agreement between Montenegro and Austria-Hungary↑

After the Montenegrin army lost its positions in Lovćen on 8 and 9 January 1916, and with the declining morale of the Montenegrin army and people following this loss, the government reached a decision to initiate peace negotiations at a meeting on 11 January. Those were the first official steps which Montenegro took towards ceasing resistance to the Austro-Hungarian armed forces. The attempt to thus secure a political future for the country was also confirmed by a telegram which King Nikola I sent to the Austrian Emperor, in which he asked for dignified conditions for a truce.[20] A letter addressed to the Russian Emperor Nicholas II also outlined the reasons behind such Montenegrin actions, and begged Russia not to condemn the steps which Montenegro took and not to deprive it of its patronage.[21]

However, on 11 January, members of the Austro-Hungarian parliament revealed that the condition for a truce was the unconditional capitulation of Montenegro.[22] As fighting continued, the Montenegrin side agreed to having its army demobilized under Austrian control and to surrendering its arms to the Austrian military forces. With little choice but to agree to the unconditional surrender of arms, the Montenegrin politicians hoped that this may enable them to initiate peace negotiations.[23]

In resisting the difficult conditions of surrender, General Janko Vukotić (1866-1927), Chief of Supreme Command Headquarters of the Montenegrin army, issued an order on 18 January 1916, stating that the King, in agreement with the Command and the government, while counting on assistance from the Allies, had decided to send its last defending forces to Scutari. If the army failed there, it would retreat towards Drač (Durres) and unite with the – Allies, and follow the course of events from there on.[24]

The order left a freedom of choice to each soldier: “those who did not want to join the defense of Scutari” were allowed to stay at home.[25] The content of the former was contrary to the news that the Montenegrin government had asked for truce, or that the final battle would take place at Carev Laz. While the measures for the army’s retreat were being undertaken, King Nikola left Montenegro on 19 January and set off to Scutari. He stayed there until 20 January, and then arrived in Medova (San Giovani di Medua) on 21 January with his entourage.

Apart from Mirko, Prince of Montenegro (1879-1918), the King’s son, three Ministers and the Chief of Supreme Command Headquarters were the only ones who stayed in the country. The government which they formed reached a decision on 21 January to cease the retreat of the Montenegrin army. In fact, the government “decided to dispense the army from its positions and consequently the army would not exist, and there would only be people”.[26] General Janko Vukotić, Chief of Headquarters of the Montenegrin army delivered the government’s decision in the form of “Order No. 128 to the Entire Montenegrin Army” from 21 January to commanders in order for them to instruct the regional units to dismiss the army and let them go home”.[27] The Montenegrin army thus ceased to exist.

In one of the four documents received by the Montenegrin government on 21 January, The Austro-Hungarian command sternly called for the Montenegrin government to promptly “send its military delegates in order for the manner of surrender of arms to be determined”.[28] In acting according to the requests of the Austro-Hungarian army, which was a formality considering Order No. 128.

The Provisions of Arms Surrender: A formal or actual act of Surrender of Montenegrin Army↑

The Provisions of Arms Surrender by the Montenegrin army were signed on 25 January. The Provisions were signed by the Montenegrin representatives, by Jovan Šipčić and by Victor Weber von Webenau (1861-1932) acting on behalf of Austria-Hungary. By the time the Provisions were signed, Austro-Hungarian troops had already occupied Podgorica on 22 and 23 January, Bar and Ulcinj (Dulcigno) on 22 January, Danilovgrad and Nikšić on 23 January, Kolašin and Andrijevica on 25 January. Cetinje was taken earlier, after the fall of Lovćen on 11 January 1916.

Despite the fact that the Provisions of Surrender were signed, the peace negotiations never took place. The Austro-Hungarian government would not agree to it since the members of a “rump government” did not have the authorization to negotiate. Negotiations with the “rump government” were cancelled and the country was placed under military rule. The Provisions of Arms Surrender from 25 January 1916 are interpreted as an act of capitulation of the Montenegrin army, which ended the resistance to Austro-Hungarian armed forces, but there are some who object to this interpretation. Namely, even though the document contains elements of a complete military capitulation, from the aspect of its legal validity, there is the issue of the lack of authorization of persons who signed it.

Another issue which arises regarding the Provisions of Arms Surrender by the Montenegrin army is the extent to which they actually produced the implied effect. The issue concerns Order No. 128 of the Chief of Supreme Command Headquarters from 21 January in which he dismissed the Montenegrin army, while the Supreme Command Headquarters, reduced only to General Janko Vukotić, was dissolved after he was relieved of duty. With the implementation of the decision, the Montenegrin army ceased to exist as an organized armed force.

Resistance to the enemy had already been terminated even before the Provisions of Arms Surrender were signed. The document formally determined the extent to which the Montenegrin army would be subdued, and the supremacy of the Austro-Hungarian military power. It acknowledged the existing state of affairs. According to the Provision of Arms Surrender, Montenegro did not cease to exist as a subject of international law even though it lost its army. However, the capitulation of its army made it impossible for Montenegro to turn its formal legal existence into a legal state reality. By dissolving the army and withdrawing from the war, Montenegrin governing circles lost serious international support aimed at restoring the country. The appeals they addressed to the Allied governments were met with declining sympathy as the movement to unite the Yugoslav peoples grew.

International Subjectivity of Montenegro: The work of the Government-in-exile after King Nikola’s departure from Montenegro↑

Having left Montenegro, King Nikola reached France via Italy. At first, it was decided that his place of residence would be in Lyon, but he was later moved to Bordeaux. Since May 1916, he was located in Neuilly near Paris. Prime Minister Lazar Mijušković (1867-1936) and Minister Andrija Radović were also in exile. The Montenegrin court in exile was accompanied by the diplomatic corps which consisted of representatives of only a few countries - Russia, Serbia, France, Italy and Great Britain.

During the first days of its exile, the government tried to justify the initiated peace negotiations and the capitulation of the Montenegrin army before the eyes of the Allies and the world public. The Prime Minister in exile put forth the greatest effort in these matters. However, the position of the Allies towards Montenegro and the Montenegrin dynasty was cold. The press in the Allied countries openly wrote about the blasphemous behavior of Prime Minister Mijušković’s government in January 1916. In mid-March 1916, Russia refused King Nikola’s request to travel to Petrograd.[29]

Despite the hostility of the Allies, King Nikola and the Ministers surrounding him continued to promote their “war goals”. They were essentially requests for the restoration of Montenegrin state independence connected with territorial expansion. Claims for new territorial borders were made without any political tact. In his letter from Bordeaux dated 19 March 1916, Lav Islavin, the Russian Emissary to the Montenegrin Court, notified Minister Sazonov that King Nikola was concerned for the fate of Montenegro, and allowed for the possibility of joining the alliance of Slavic states (Une confederations des Etats Slaves) under Russian guarantee and protectorship as a condition for securing its independence.[30] Nevertheless, King Nikola presented Islavin with a memorandum on Montenegrin territorial claims.[31] Allied Powers made no reply to the Montenegrin proposition. It was not found to be suitable by anyone, neither Russia, nor Serbia, and especially not Italy.

Similar foreign political efforts were at first made by Andrija Radović, the following Prime Minister in exile, and subsequently by Milo Matanović (1871-1955). There were also noticeable shifts. They emphasized a “nationalist policy in the spirit of the union” in agreement with Serbia as their national task.[32] Both of them suggested a union which would be achieved by King Nikola abdicating in favor of Crown Prince Aleksandar, who would later be Aleksandar I, King of Yugoslavia (1888-1934). The union was to be aimed at creating a Yugoslav state.[33]

The King tried to end the crisis not only by forming a new government led by Prime Minister Evgenije Popović, but also by changing the course of their foreign policy. Even though he wanted an independent Montenegro to be restored, King Nikola strove to present himself as a supporter of a wider Yugoslav union. The note which Evgenije Popović addressed to the Serbian government, proposing a renewal of negotiations on a real union, which ended in mid-1914, was in line with such a foreign policy position. It seemed that Russia was also keen on the idea of a real union in late 1917.

The idea of Yugoslav unification was gaining more and more support at the time. After the Corfu Declaration in 1917, which determined the organization of the future Yugoslav state as a unitary federation, returning to the project of a real union and preservation of two dynasties was a politically irrational solution for Serbia. After the Corfu Declaration was adopted, a new memorandum regarding Montenegrin territorial claims was sent to the British government on 27 September 1917 by George Graham[34], chargé d’affaires to the Montenegrin Court. The fact that the claim for the restoration of state and territorial borders was written by King Nikola himself proves the gravity with which he approached the matter.

Positions of the Allies↑

The positions of the Allies, Great Britain and America, concerning the aims of the war and the principles of the future structure of relations in Europe, which did not include restoration of the Montenegrin state, were the next basis of his policy in exile.

First, in his speech before the Congress and the representatives of the British Trade Union given on 5 January 1918, Prime Minister David Lloyd George (1863-1945) stated that America and Britain agreed that carving up Austro-Hungarian territory was not their war goal.[35] The declared position denied the possibility of implementing the concept of Montenegrin territorial expansion. As for the restoration of the Montenegrin state and other occupied countries and the acceptability of such a solution, Lloyd George’s speech left no doubt. The British Minister supported the restoration of the concept existing before the war. A similar conclusion could be drawn from the World Peace Program in fourteen points, contained in President Woodrow Wilson’s (1856-1924) address to Congress on 8 January 1918. Among other things, it said that Belgium had to be “evacuated and restored” without any attempt to limit its sovereignty, and then that “Romania, Serbia and Montenegro had to be evacuated and the occupied territories restored”.[36] The program also included the territorial unity of Austria-Hungary.

These documents were not firmly defined objectives of the Allied policy. The changing political positions of the Allies regarding the principles of regulating world order, and thus regarding Montenegro, were similar in their instability and even contradiction. This poses a dilemma regarding the extent to which Prime Minister Lloyd George’s speech and President Wilson’s program actually reflected the real policy of their respective countries towards the future of Montenegro, and how much they actually represented a form of political improvisation and were the consequence of confusion. This particularly refers to the policy of Great Britain, while America can be judged more leniently for being less informed.

With a change in position regarding the survival of Austro-Hungary, the position regarding the Yugoslav issue also changed. By supporting the Yugoslav union, British policy supported Montenegro’s entry into the Yugoslav state. Similar positions of the British War Cabinet on its policy towards Montenegro were expressed in the Balfour memorandum in late July 1918.[37] Although the USA tended to follow British policy, it could be argued that the American relations to Montenegro contained ambiguous political actions, at least in 1918. Apart from the positions concerning the restoration of Montenegro, contained in President Wilson’s points, the illusion of American support for the Montenegrin claims was encouraged by granting Montenegro exequatur to establish diplomatic representation in Washington.

With the Great Powers adopting the program of Yugoslav union in late 1918 based on the principles of nationality and self-determination of “one people with three names”, a negative decision regarding the further existence of Montenegro as an independent country had essentially been reached. Refusing to accept such a solution, the King and the government in exile tried to change the position of the Allies in mid-1918 and even afterwards. Along with Britain and the USA, steps were also made towards Italy and France in that respect. The only one expressing interest in Montenegro was Italy. By late 1918, King Nikola and the exile government frequently wavered between the two solutions. Thus, instead of sending a memorandum on territorial claims, they shifted their focus back to the Yugoslav question. When the creation of a Yugoslav state became a certainty, King Nikola tried to preserve Montenegrin status within it through an adequate decentralized form of state organization. This was a distinct criticism of the unitary concept defined by the Corfu Declaration in 1917 and of the principle of centralism that the future state was to be based on. He advocated “the creation of a federal state which would preserve the autonomy of all the regions which constitute it”.[38] Moreover, he advocated a confederate principle, as opposed to a federal one.[39]

Concerned by the rapid advance of the Serbian army, Montenegrin Ministers called for “an order to be issued to the Italian Expedition Corps in Albania to enter Montenegro ‘in order for it to be liberated solely by Italian troops’”.[40] A solution was also sought in the efforts to organize resistance within the country. By forming a council consisting of King Nikola’s supporters, a rebellion would be instigated in the event of the entry of Serbian troops.[41]

In October 1918, King Nikola requested to be transferred to Albania. Although even the Italian government opposed such a step proposed by the King, the position of the French government was the deciding factor. The French government “refused his request to join the East Army or return to Montenegro before the Allied troops banish the enemy from it”.[42] Even though the French government had declared that the Allied troops entering Montenegro did not mean an abolishment of the sovereignty of the Montenegrin state, and that the sovereign rights of Montenegro would be upheld and all decisions made in the name of King Nikola, which both British and Italian governments confirmed, it was adamant, nevertheless, in its determination to oppose the efforts which Italy and King Nikola were making to prevent a union between Serbia and Montenegro. This was noticeable in the following days when King Nikola requested to be transferred to Italian territory. The French government then insisted on keeping the King in France.[43]

Liberation of the Country and the Method for Resolving the Political Future of Montenegro↑

The Supreme Command of Allied Armies formed the “Troops of Scutari” for operations aimed at liberating Montenegro. The division was mainly composed of Serbian army units, but “some French units were included in the troops along with the Serbian ones”.[44] Apart from a military task, the division also had a political task. It consisted of “working on uniting Serbia and Montenegro in a friendly way through the members of the Montenegrin Council and Montenegrin people without any coercion on behalf of our troops”.[45] For this purpose, following the instructions of the Serbian Supreme Command from October 1918, members of the Montenegrin Council were sent to Montenegro together with the Scutari Division and Svetozar Tomić (1872-1954) the official representative of the Serbian government and Chief of Montenegrin Department in the Serbian Ministry of Foreign Affairs.[46]

Even though the number of those in favor of the union was substantially larger, the power of King Nikola’s supporters could not be disregarded either. A massive rally was quickly organized in order to use the sentiment of the people to officially proclaim the union. Podgorica was chosen for the scene of the rally since it had a larger number of union supporters than Cetinje.

The election of Members of Parliament was not done according to the 1907 Election Law of the Kingdom of Montenegro. It was decided that delegates would be chosen at public rallies (Captaincies elected ten delegates, counties elected fifteen while the town municipalities elected five to ten delegates). The delegates were to meet on 19 November and elect Members for the National Assembly which was to meet in session on 24 November. Considering the election method, the result was that mainly the supporters of an unconditional union were elected (the Whites), while the supporters of a union with preserved Montenegrin integrity (the Greens), being a minority, failed in fighting for their beliefs and could not elect their Members. 165 members were chosen indirectly, through delegates.

Internal and International Significance of the Podgorica Assembly and its Decisions↑

The Assembly commenced on 24 November, and the session lasted until 29 November, 1918. The most important decisions of the Assembly were made at the session on 24 November. It was on that day that a resolution was adopted according to which it was decided to 1) depose King Nikola I Petrović Njegoš and his dynasty from the Montenegrin throne, 2) unite Montenegro with its sister Serbia into one large country under the Karadjordjević dynasty, and thus united enter the common fatherland of our people with three names - Serbs, Croats and Slovenes 3) to elect a national council consisting of five persons to handle the affairs until the union of Serbia and Montenegro was finalized, 4) to inform the former Montenegrin King Nikola I Petrović, the Serbian government, the friendly Allies and all neutral countries of this decision.[47]

The Assembly in Podgorica proclaimed an unconditional union of Montenegro with Serbia. On 28 November, the Assembly in Podgorica elected members of the National Executive Council, which had a task to act as a temporary government and govern Montenegro until the union. A delegation of eighteen people was also chosen and entrusted with a task of traveling to Belgrade and delivering the Decision of the Podgorica Assembly to the Serbian Crown Prince.

Other Allied countries were notified of the decisions of the Assembly at the time of these events, after the Russian revolution and President Wilson’s Fourteen Points, the principles of nationality were fully affirmed, i.e. the people’s right to self-determination and to creating their own state, but the decisions of the Montenegrin Assembly were not interpreted nor accepted as such by the Allied countries. Serbia also showed reluctance to support them internationally and acknowledge them as a form of the right to self-determination, since it kept maintaining diplomatic relations with the Montenegrin government. On 28 December 1918, Tihomir Popović,[48] accredited diplomatic representative to King Nikola’s court, delivered a note on behalf of the Cabinet of Stojan Protić (1857-1923), which stated that “the functions of the Serbian diplomatic representative are terminated since the union between Montenegro and Serbia came into effect on 4 December”.[49]

The unfavorable attitude of the Allied countries towards the decisions of the Podgorica Assembly remained unchanged even later. The British government reacted to the union achieved in such a way with a “willingness to protect the Montenegrin interests”. As a result, the British and American governments took a joint step contained in a memorandum to the State department from 4 January 1919, which indicated the “undesirability of such a precedent”, considering the position of the Allies that any decisions on territorial changes should be placed in the hands of the Peace Conference. The British government had the intention to instruct its representative in Belgrade, 1) to lodge a formal protest against the fait accompli in Montenegro and the attempt to interfere with the decisions of the Peace Conference and 2) to inform them that England would not acknowledge such entitlement”.[50]

When the situation concerning the union became complicated in Montenegro due to the Christmas Mutiny in early 1919, the Allies considered an Anglo-French or Anglo-American occupation of its territory in order to prevent a civil war. President Wilson particularly advocated an intervention in favor of King Nikola. As a reaction to a letter he had received from the King on 7 January 1919, President Wilson ordered for the Belgrade authorities to be warned that America favored both Montenegro and Serbia equally, but he felt that the Yugoslav issue was being aggravated by the apparent efforts to resolve by arms that which should be defined by agreement and consent.[51]

Such a course of events raised the expectations of the Montenegrin government in exile that the Peace Conference could be a great opportunity for a favorable resolution of their claims for a restoration of the Montenegrin state. However, the events at the Conference proved that such political speculations were unrealistic. At the Peace Conference in Paris in 1919, the Montenegrin issue “was not a real problem, but merely a threat of a problem, and certainly not a problem of importance”.[52] The issue was raised by Baron Sidney Sonnino (1847-1922), who asked for the question of Montenegrin participation to be resolved at the beginning of the conference, stating that it too should have a representative at the conference like the other Allied countries. Discussion on the matter was led in light of the situation created by the proclaimed union, and the French Minister of Foreign Affairs phrased the basic issue in the form of a question of whether “Montenegro was to be considered a separate state, with a separate representative, or as a part of the SHS Delegation”.[53] President Wilson was particularly persistent in defending the Montenegrin right to a separate representation. In his mind, Serbia dispatched its troops to Montenegro illegally, and such display of force was contrary to the principle of self-determination of the people. Prime Minister Lloyd George also supported the beliefs of the American President. Considering the general principles which the work of the Conference was based on, a general solution according to which Montenegro would “be represented” at the conference had to be adopted. However, it all ended at that. Even though the name of Montenegro was marked at the conference table in the same way as the other participants, the position of its delegation remained empty.

Conclusion↑

Due to military exhaustion in the previous two wars, lack of arms, political discord between the governing circles and their support for the neutrality of the country, and the prevalent sentiment among the people to enter the war on the side of Serbia and Russia, Montenegrin war efforts could not have yielded better results. Moreover, apart from all the criticism which the autocratic regime of King Nikola I deserved, lack of military doctrine and clearly defined war objectives, it can be said that during the first two years of the war, the Montenegrin Army objectively exceeded its realistic capabilities. Its role was especially priceless during the retreat of the Serbian Army when it acted as its strategic protector.

Instead of ordering the retreat of their own army as well, Montenegrin governing circles, fearing the development of the unionist movement, fled Montenegro and surrendered to the diplomacy of the Great Powers. Despite their best efforts, its governments in exile failed to meet with political understanding because of its bad reputation. The extent of their misconception and the lack of perception of the political reality in fully relying on the diplomacy of the Great Powers became obvious at the Paris Peace Conference.

Radoslav Raspopović, University of Montenegro

Section Editors: Milan Ristović; Tamara Scheer; Richard C. Hall

Notes

- ↑ Notovich, F.T.: Diplomaticeskaia borba v godi pervoi mirovoi vonii [The Diplomatic Battle During World War I], Moscow et al., 1947, p. 15. More closely defined activities for its realization were the following: 1) keeping Romania at the side of the Triple Alliance, 2) establishing close friendly relations with Bulgaria and turning it into a Balkan sentinel for Austro-Hungary and Germany, and rewarding it with Serbian Macedonia, 3) creating a new Balkan alliance under the patronage of Austria-Hungary and Germany, which would consist of Romania, Bulgaria and Greece against Russia and the Entente, 4) territorial division of Serbia and Montenegro with an “independent Serbia” reduced to insignificance and linked to Austria-Hungary by bonds of gratitude for gaining a portion of Montenegro. See Kennedy, Paul: The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers, Economic Change and Military Conflict, Podgorica 1999; Raspopović, Radoslav M.: Diplomatija Crne Gore 1711-1918 [Montenegrin Diplomacy 1711-1918], Podgorica et al., 1996, pp. 599-639; Mitrović, Andrej, Prodor na Balkan: Srbija u planovima Austro-Ugarske i Nemačke: 1908-1918 [Breaking into the Balkans: Serbia in the Plans of Austro-Hungary and Germany: 1908-1918], Belgrade 2011; Rakočević, Novica: Politički odnosi Crne Gore i Srbije 1906-1918 [The Political Relations of Montenegro and Serbia 1906-1918], Cetinje 1918.

- ↑ A continuous line of “Allied” - actually vassal German countries - would stretch from Berlin to Baghdad. The potential power of Serbia - a migration centre for the Austrian south Slavs - would be destroyed, while Romania would be tamed by means of an enlarged Bulgaria, all of which was meant to deliver a blow to the liberation movement of Southern Slavs and Romans in the Habsburg Empire and consolidate it from within.

- ↑ Rakočević, Politički odnosi Crne Gore i Srbije [The Political Relations of Montenegro and Serbia 1906-1918], p. 19.

- ↑ Aleksandar Aleksandrovič Girs, Advisor to the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs 1910, Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary for the Russian government in Montenegro (1912-1915).

- ↑ Pisarev, Y.A..: Velikie derzhaviy i Chernogorija v godû pervoj mirovoj vojny, Mezhdunarodnye otnoshenija na Bakanah [Large Countries and Montenegro During World War I, International Relations in the Balkans], Moscow 1974.

- ↑ Baron Eduard Otto, Austro-Hungarian Envoy in Cetinje from 4 December 1913 to 7 August 1914.

- ↑ Pisarev, Velikie derzhaviy i Chernogorija [Large Countries and Montenegro], p. 135.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ General Božidar Janković was appointed military delegate to the Montenegrin Headquarters. Apart from him, Headquarters Colonel Petar Pešić, Colonel Engineer Borivoje Nešić and Infantry Lieutenant Colonels Dragoljub Mihajlović and Djordje Paligorić were placed at the disposal of the Montenegrin Army Headquarters. Veliki rat Srbije za oslobođenje Srba, Hrvata i Slovenaca [Serbia’s Great War to Liberate Serbs, Croats and Slovenes], knj. I-1914, Belgrade 1924, pp. 31-33.

- ↑ AVPRI (Arhiv vneshne politiki Rossiskoi imperi) [AVPRI (Archive of Foreign Policy of the Russian Empire)], F. Kanceljarija 1915, p. 63.

- ↑ Ibid, p. 233.

- ↑ General Martinović allegedly did not agree with such instructions of the King on Montenegrin territorial boundaries. In his political memoirs, he noted that he replied to the King: “My Lord, I believe that this would be exaggerated, because if Sarajevo, which does not have a good background in the south, were to remain within Montenegro, cut off from the rest of Bosnia, this would cause a complete economic disaster and migration to great moral and material detriment of Montenegro, since it would be our element which would be ruined and which would meet with the greatest disaster and ruin instead of the greatest joy of liberation. As for Split, this would also be asking too much to take it away from Serbia, which has no sea access other than Split. As for Bosnia, I would not go beyond Romanija and Mount Ivan, but rather leave it to Serbia. I think we should not go further than Makarska, and only take the Neretva valley with Metkovići. If we were not satisfied with the way Bosnia and Dalmatia were divided between us and Serbia, we could ask for compensation in Sandžak and the Kosovo vilayet”. Luburić, Andrija: Dokumenti II, 1930, p. 20

- ↑ According to this proposal, Montenegro would gain “Herzegovina with a portion of Adriatic coastline belonging to it (to Herzegovina), the lower part of Dalmatia all the way to the island Antivari (including Dubrovnik and Kotor), a small portion of Bosnia in the northeast, occupied by Montenegrin forces in autumn and winter without the help of Serbs, and the entire right hillside from the Drim estuary in the south all the way to Montenegrin border with Serbia. (Naturally, this included the entire territory northwards to the river Drim, the town of Skadar (Skutari) and the lake.)” That was to be the border line in the event of a division of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Dalmatia and a portion of Albania. In the event that Croatia, Slavonia and Srem were also to be divided, a portion of Montenegro would need to be enlarged. The Grand Duchess also requested for the borders between Serbia and Montenegro to be determined by Russia. Luburić, Dokumenti II, Number. 53, p. 184.

- ↑ Rakočević, Novica: Crna Gora u I svjetskom ratu 1914-1918 [Montenegro in World War I 1914-1918], Cetinje 1969, p. 82.

- ↑ Vujović, D.: Saveznici i crnogorske finansije 1914-1921 [The Allies and Montenegrin Finances 1914-1921], Istorijski zapisi, LIX, sv. 3, Titograd 1986, p. 51.

- ↑ Rakočević, Crna Gora [Montenegro in World War I], p. 88. The loan was spent on purchasing artillery, machine guns, rifles and the appropriate amount of ammunition. According to Radović’s report, the granted loan allowed for the purchase of “a half million kilograms of flour, a half million kilograms of coke and 100,000 kilograms of rice”. However, a large portion of the purchased goods was not transferred to Montenegro due to difficulties in transport.

- ↑ Rakočević, Crna Gora [Montenegro in World War I], p. 88.

- ↑ Vučković, Vojislav: Diplomatska pozadina ujedinjenja Srbije i Crne Gore [The Diplomatic Background of the Unification of Serbia and Montenegro], Belgrade 1950, p. 248.

- ↑ Operacije crnogorske vojske u I svjetskom ratu [Operations of the Montenegrin Military in World War I], Vojno-istorijski institut, Belgrade 1954, p. 536; Đurišić, Mitar: Operacije crnogorske vojske 1915-1916. godine [The Operations of the Montenegrin Military 1915-1916], Vojno-istorijski glasnik, 2-3, 1995, pp. 84-109.

- ↑ Ibid, p. 516.

- ↑ In initiating peace negotiations, the government acted contrary to the resolution made by the National Assembly on 1 August 1914, and contrary to its own declaration before the Assembly made on 3 January 1916. Rakočević, Crna Gora [Montenegro in World War I], p. 162.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ The requests made by the Austro-Hungarian Supreme Command on 18 January were difficult and humiliating. Apart from surrendering all the weapons in the country, the entire Montenegrin army was also to surrender to the Austrian troops, along with the entire population which did not belong to the armed forces but was old enough to carry a weapon. They were to be imprisoned during the peace negotiations. IIRCG, AZ, Protokol rada kraljevske vlade od 29. 12. 1915. god. do 19. 2. 1916. g Istorijski institut Crne Gore, Arhivska zbirka (IICG,AZ) [Operations Protocol of the Royal Government from 29.12.1915 to 19.2.1916].

- ↑ Protokol rada kraljevske vlade od 29. 12. 1915. god. do 19. 2. 1916. g [Operations Protocol of the Royal Government from 29.12.1915 to 19.2.1916], p. 176.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Operacije crnogorske vojske u prvom svjetskom ratu [Operations of the Montenegrin Military in World War I], Belgrade 1954, p. 533.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Rakočević, Crna Gora, p. 203. Crnogorski zakonici 1711-1916, Pravni izvori i politički akti od značaja za istoriju državnosti Crne Gore [Montenegrin Legal Codes 1711-1916, Legal Sources and Political Acts Significant to the History of Montenegrin Statehood], p. 836.

- ↑ Luburić, Andrija: Kapitulacija Crne Gore [The Capitulation of Montenegro], Dokumenti I, Number 90, Belgrade 1938, p. 81. See: Živojinović, Dragolub: Crna Gora u borbi za opstanak 1914-1922 [Montenegro’s Fight for Survival 1914-1922], Belgrade 1996.

- ↑ АВПРИ, Ф. Мисия в Цетинье 1917 [AVPRI; Mission in Cetinje 1917], p. 13 and 17.

- ↑ Živojinović, Dragoljub: Kralj Nikola i teritorijalno širenje Crne Gore 1914-1920 [King Nikola and the Territorial Expansion of Montenegro 1914-1920], Istorijski zapisi, year LXI, Titograd 1988/3-4, p. 168. See Živojinović, Dragoljub R. Italija i Crna Gora 1914-1925 [Italy and Montenegro 1914-1925], Belgrade 1998.

- ↑ The minimal Montenegrin requests were the following: the border was to run ten kilometres south of the Drim estuary into the Adriatic Sea, following the water line along the left bank of the Drim to the confluence of Crni and Beli Drim, where the border line between Serbia and Montenegro would be corrected in favour of the latter all the way to Prijepolje. From there, it would run along the rivers Lim and Drina northwards to Rogatica, where it would take a turn westwards so that Montenegro would get Rogatica, Sarajevo and the surrounding areas. It would further run below Livno all the way to the coast so that the entire river Neretva and its estuary would belong to Montenegro. The entire coastline from the Neretva to Medovski bay would also belong to Montenegro. Radović, Andrija: Crna Gora u evropskom ratu [Montenegro in the European War], Slobodna misao, 5 January 1936, Number 1.

- ↑ In his paper, Diplomatska pozadina ujedinjenja Srbije i Crne Gore [The Diplomatic Background of the Unification of Serbia and Montenegro], pp. 247-248, V. Vučković claims that the main ideas of the document were the following: 1) After the victory of the Allies, a great Yugoslav state would be created, 2) it was in the interest of Montenegro to join it, because even with the territorial expansion to the Neretva with Dubrovnik, Boka Kotorska and Skadar, it could not survive economically, 3) Europe would be governed by democratic principles which could not be reconciled with the autocratic principles of kings, 4) only a complete union of Serbia and Montenegro could save the people from strife and foreign intrigues, 5) it was natural for the Serbian Crown Prince to bear the crown of the united country as a representative of the people which suffered the greatest loss in the war, 6) succession of throne could alternate between the two dynasties, 7) the Russian Emperor would negotiate the union.

- ↑ Sir George Graham, diplomatic representative of Great Britain from June 1917 to December 1918 as Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary to the Montenegrin government in exile.

- ↑ Janković, Dragoslav / Krizman, Bogdan: Građa o stvaranju jugoslovenske države [On the Creation of the Yugoslavian State] (1. I-20. XII-1918), Belgrade 1934, Doc. Number 2. See also Živojinović, Dragoljub R.: Kraj Kraljevine Crne Gore [The End of the Kingdom of Montenegro], Belgrade 2002; Živojinović, Dragoljub R. Nevoljni ratnici, Velike sile i Solulunski front [Unwilling Warriors, the Great Powers and the Salonika Front], Belgrade 2010; Raspopović, Radoslav: Istorija diplomatije Crne Gore 1711-1918 [The History of Montenegrin Diplomacy 1711-1918], Podgorica 2009, pp. 550-557.

- ↑ Ibid, Doc. Number 7.

- ↑ The Balfur Memorandum was a sort of instruction to Lord Derby, the British Emissary in Paris, on the policy of the British government towards Montenegro. The union of Montenegro and Serbia was said to be in accordance with the nationality principle. Moreover, “it was also emphasized that the British government had no intention of reaching a final decision until the people of Montenegro expressed its will”. The attitude towards King Nicholas was reserved, due to the belief that he and his ministers did not represent the will, aspirations and sentiment of the people, and that as such they failed to act in accordance with its interests. The creation of a Yugoslav state was supported. The letter also expressed a belief that Montenegro would represent a region slightly larger than a county within the state. Živojinović, Dragoljub, R.: Velika Britanija i problem Crne Gore 1914-1918 [Great Britain and the Problem of Montenegro 1914-1918], Belgrade 1977, p. 515.

- ↑ Živojinović, Kralj Nikola i teritorijalno širenje Crne Gore [King Nikola and the Territorial Expansion of Montenegro], p. 173. Cjelokupna djela Nikole I Petrovića Njegoša, Vol. IV, Govori [The Entire Work of Nikola I Petrović-Njegoš, Vol. IV, Speeches], Cetinje 1969, p. 202; See Živojinović, Dragoljub, Nevoljni saveznici 1914-1918 [Unwilling Allies 1914-1918], Belgrade 2000; Rastoder, Šerbo: Skrivana strana istorije, Crnogorska buna i odmetnički pokret 1918-1919 [The Hidden Side of History, the Montenegrin Rebellion and the Renegade Movement 1918-1919], Cetinje et al., 2005.

- ↑ Ibid, p. 202.

- ↑ Živojinović, Dragoljub: Pitanje Crne Gore i mirovna konferencija 1919 [The Issue of Montenegro and the 1919 Peace Conference], Belgrade 1992, p. 7. See Rastoder, Šerbo: Crna Gora u egzilu [Montenegro in Exile], Podgorica 2004.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 8.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 9.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Vujović, Dimitrije (Dimo): Ujedinjenje Crne Gore i Srbije [The Unification of Montenegro and Serbia], Titograd 1962, p. 304 ff.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 305.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Vujović, Dimitrije (Dimo): Podgorička skupština 1918 [The Podgorica Assembly 1918], Zagreb 1989, p. 228.

- ↑ Diplomatic representative of Serbia to the Montenegrin Court as chargé d'affaires, 1917-1918.

- ↑ Vučković, Diplomatska pozadina ujedinjenja Srbije i Crne Gore [The Diplomatic Background of the Unification of Serbia and Montenegro], p. 256. Apparently, in this case, 4/17 December is associated with the arrival of the Montenegrin delegation to Belgrade, consisting of Gavrilo Dožić, Janko Spasojević and Milisav Raičević, which delivered the Decisions of the Podgorica Assembly to Crown Prince Aleksandar and requested a union of Montenegro and Serbia.

- ↑ Vučković, Diplomatska pozadina ujedinjenja Srbije i Crne Gore [The Diplomatic Background of the Unification of Serbia and Montenegro], p. 256, p. 255.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Mitrović, Andrej: Jugoslavija na konferenciji mira u Parizu 1919-1920 [Yugoslavia at the Paris Peace Conference 1919-1920], Belgrade, 1969, VII.

- ↑ Živojinović, Dragoljub: Pitanje Crne Gore na konferenciji mira u Parizu [The Issue of Montenegro at the Paris Peace Conference], Belgrade 1992, p. 31.

Selected Bibliography

- Veliki rat Srbije za oslobođenje i ujedinenje Srba, Hrvata i Slovenaca, 1914 (Serbia’s Great War to liberate Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, 1914), volume 1, Belgrade 1924: Ujedinjenje, 1924.

- Janković, Dragoslav / Krizman, Bogdan: Gradja o stvaranju jugoslovenske države, 1.1.-20.12.1918 (On the creation of the Yugoslavian state, 1.1.-20.12.1918), Belgrade 1964: Institut društvenih nauka.

- Kennedy, Paul M.: The rise and fall of the great powers. Economic change and military conflict from 1500 to 2000, New York 1987: Random House.

- Luburić, Andrija: Kapitulacija Crne Gore. Dokumenti 1, Belgrade 1938.

- Luburić, Andrija: Kapitulacija Crne Gore. Dokumenti 2, Belgrade 1940.

- Mitrović, Andrej: Prodor na Balkan. Srbija u planovima Austro-Ugarske i Nemačke, 1908-1918 (A breakthrough in the Balkans. Serbia in Austro-Hungarian and German planning, 1908-1918), Belgrade 1981: Nolit.

- Mitrović, Andrej (ed.): Jugoslavija na konferenciji mira 1919-1920 (Yugoslavia at the peace conference 1919-1920), Belgrade 1969: Zavod za izdavanje udžbenika Socijalističke Republike Srbije.

- Notović, F. T.: Diplomaticheskaja bor'ba v godû pervoj mirovoj vone (The diplomatic battle during World War I), Moscow 1947.

- Pavićević, Branko / Raspopović, Radoslav: Crnogorski zakonici. Pravni izvori i politički akti od značaja za istoriju državnosti Crne Gore, 1796-1916 (Montenegrin legal codes. Legal sources and political acts significant to the history of Montenegrin statehood, 1796-1916), volume 1-5, Podgorica 1998: Istorijski Institut Republike Crne Gore.

- Petrović-Njegoš, Nikola: Cjelokupna djela Nikole I Petrovića Njegoša. Govori (The entire work of Nikola I Petrović-Njegoš. Speeches), volume 4, Cetinje 1969: S.N..

- Pisarev, Y. A.: Velikie derzhaviy i Chernogorija v godû pervoj mirovoj vojny, Mezhdunarodnye otnoshenija na Bakanah (Large countries and Montenegro During World War I, International Relations in the Balkans), Moscow 1974.

- Rakočevic, Novica: Crna Gora u prvom svjetskom ratu 1914-1918 (Montenegro in the First World War 1914-1918), Cetinje 1969: Istorijski Institut Titograd.

- Rakočević, Novica: Politički odnosi Crne Gore i Srbije, 1903-1918 (Political Relations between Montenegro and Serbia 1903-1918), Cetinje 1981: Istorijski institut SR Crne Gore u Titogradu.

- Raspopović, Radoslav M.: Diplomatija Crne Gore, 1711-1918 (Montenegrin diplomacy, 1711-1918), thesis, Podgorica; Belgrade 1996: Istorijski institut Crne Gore; Novinsko izdavačka ustanova Vojska.

- Raspopović, Radoslav M.: Istorija diplomatije Crne Gore, 1711-1918, Podgorica 2009: Univerzitet Crne Gore.

- Rastoder, Šerbo: Skrivana strana istorije. Crnogorska buna i odmetnički pokret 1918-1929 (The hidden side of history. The Montenegrin rebellion and the Renegade movement 1918-1919), Cetinje 2005: Centralna Narodna Biblioteka Crne Gore Djurdje Crnojević.

- Rastoder, Šerbo: Crna Gora u egzilu, 1918-1925 (Montenegro in exile, 1918-1925), volume 1, Podgorica 2004: Istorijski institut Crne Gore: Almanah.

- Treadway, John D.: The falcon and the eagle. Montenegro and Austria-Hungary, 1908-1914, West Lafayette 1983: Purdue University Press.

- Vojnoistoriski institut: Operacije crnogorske vojske u Prvom svetskom ratu (Operations of the Montenegrin military in World War I), Belgrade 1954: Vojno delo.

- Vučković, Vojislav: Diplomatska pozadima ujedinjenja Crne Gore i Srbije (The diplomatic background of the unification of Serbia and Montenegro): Jugoslovenska revija za međunarodno pravo, volume 2, Belgrade 1950.

- Vujović, Dimitrije-Dimo: Podgorička skupština 1918 (The Podgorica assembly 1918), Zagreb 1989: Školska knj. Stvarnost.

- Vujović, Dimitrije-Dimo: Ujedinjenje Crne Gore i Srbije (The unification of Montenegro and Serbia), Titograd 1962: Istorijski institut narodne republike Crne Gore.

- Živojinović, Dragoljub R.: Crna Gora u borbi za opstanak, 1914-1922 (Montenegro’s fight for survival 1914-1922), Belgrade 1996: Vojna knjiga.

- Živojinović, Dragoljub R.: Kraj Kraljevine Crne Gore. Mirovna konferencija i posle 1918-1921 (The end of the kingdom of Montenegro), Belgrade 2002: Službeni list SRJ.

- Živojinović, Dragoljub R.: Nevoljni ratnici. Velike sile i Solunski front, 1914-1918 (Unwilling warriors. The Great Powers and the Salonika front, 1914-1918), Belgrade 2008: Zavod za udžbenike.

- Živojinović, Dragoljub R.: Velika Britanija i problem Crne Gore 1914-1918 (Great Britain and the problem of Montenegro 1914-1918): Balcanica, volume 8, Belgrade 1977.

- Živojinović, Dragoljub R.: Italija i Crna Gora, 1914-1925. Studija o izneverenom savezništvu (Italy and Montenegro, 1914-1925. A study of betrayed alliance), Belgrade 1998: Službeni list SRJ.

- Živojinovi, Dragoljub R.: Pitanje Crne Gore i mirovna konferencija 1919 (The issue of Montenegro and the 1919 Peace Conference): Istorija XX vijeka, Zbornik radova XIV-XV, Belgrade 1992.