Introduction↑

The issue of civilian morale is a key topic in the analysis of the First World War. In fact, the demands of such a prolonged war implied a deep involvement of societies and put states’ social cohesion and organizational skills to the test. From 1914-1915 on, the creation of the “home front” concept entailed that civilians were also “combatants” and thus morale and consent assumed an increasing importance for mass warfare.[1] Indeed, at first, civil and military authorities knew little about behavioural issues, motivation and measures to bolster morale; therefore, as argued by historian John Horne, the discovery of the importance of morale – conceived as a “wartime offshoot” of public opinion – was a part “of the process of mobilisation” led by the states. The concept of morale belongs to the military sphere and during the war this issue acquired an increasing complexity. It was often identified as a sort of “collective loyalty” to the national effort.[2]

It is difficult to find a working definition because morale is an amorphous psychological condition and not easily measurable. It is therefore important to use this term with caution, bearing in mind its wartime ambiguities, connotations and limits. From a “top-down” perspective one can consider morale as “public spirit”, a notion that in wartime implies a consent in which “behaviour and action are involved”, a psychological state which enables people to endure difficulties, overcoming complaints and defeatism.[3] As a consequence, morale in World War I was a concept that summarized willingness to fight, confidence, sense of duty, cohesion, mutual solidarity. On the other, if this issue is analyzed from below, there is a large spectrum of subjective experiences influenced by many factors, such as the degree of integration of populations into the nation-state, military operations, prospects of victory, state intervention, social and economic upheaval, uncertainty, fears, suffering, but also the desire for a new society.

These different situations – which are intertwined with other issues, such as class, gender, ethnic minority and urban/rural setting – contribute to draw an imaginary curve of optimism, pessimism, indifference or even anger. Civilian morale, as Pierre Renouvin (1893-1874) argued, is a sort of “geological stratification”; at its deepest level, morale is rational-based and expresses slow-formed convictions which correspond to the “national sentiment”; in a second level one can find the stable attitudes that are influenced by war but reflect pre-war attitudes; and finally, on the surface, the immediate emotions, the spontaneous reactions to the “brutal events of everyday life in wartime”.[4] The issue of the “public spirit” became important in the late 1960s, when French historians tried to analyze the “masses’ attitudes” on the home front; this historiographical shift paved the way for new social history studies – such as Jean-Jacques Becker’s ground-breaking study on 1914 which analyzed public opinion in a national/regional framework using new archival sources (schoolteacher reports, prefect summaries, censorship boards and newspapers).[5]

In the 1980s civilian morale was analyzed as a factor resulting from economic conditions, state controls and propaganda. Since the late 1990s, the popular mood – especially in the French and British cases – has been considered as part of the “cultural experiences” of mobilization. Recently, following the paradigm of war as a “state of exception”, historians have shifted the analysis towards the relationship between war and the rise of “security nation-states”, a sort of first step that led to the control of public opinion in the totalitarian regimes.[6] Although aware of its importance, this paper will not analyze propaganda in detail, as this theme deserves a separate analysis, but will focus on certain issues: the general development of wartime morale, the “state-discovery” of civilian morale and the means used to monitor it, the key factors that influenced morale, and finally, the national cases. In fact, although states faced a similar challenge, civilian morale had different patterns and manifestations, following peculiar situations and wartime mobilisations.

General Trends of Civilian Morale 1914-1918↑

From the Outbreak of the War to the Rise of “National-Security States” 1914-15↑

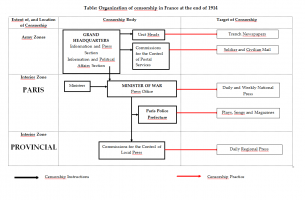

The first expressions of the population’s mood at the outbreak of war were manipulated and emphasized. Governments and interventionist newspapers created the “myth” of collective enthusiasm to justify the declaration of war in 1914 and to impose a social and political truce (“Burgfrieden”, “union sacrée”). Indeed, the “August experience” was far from unified; since the late 1970s, historian Jean-Jacques Becker has challenged this myth in the French case, and the research done during the following decades has shown that in almost every belligerent state – from Great Britain to Germany, France to Austria-Hungary, the British Dominions to the United States – popular responses were mainly comprised of “stupefaction”, “surprise” and “dismay” rather than “war enthusiasm”.[7] Notwithstanding the initial hesitations, a sense of “defensive patriotism” prevailed among populaces, especially where the national territory was invaded, as in Belgium, France, East Prussia and Serbia; in the Ottoman Empire there were spontaneous expressions of popular support for the government after the July panic.[8] When the mobilisations took place, the state used the “August spirit” – a shared fate, myth of regeneration and national reawakening that overcame political and class divisions – as an “ideological instrument” to promote a sense of national community and support morale on the home front.[9] The governments underlined the “moral” and legitimate “self-defensive” nature of the war and used patriotism and cooperation as emotional moulds.[10] In this phase, as state and military authorities conceived home front morale as an absence of social unrest, they tried to manage public opinion in a traditional way, that is to say through propaganda (“positive mean”), censorship (“negative mean”) and enforcing forms of emergency powers to suppress dissent. The battles of autumn 1914 marked the passage from the “illusions” to the “realities” of a long-lasting war of attrition and led to the first deterioration of morale; this situation entailed the creation of “home fronts” and led governments to develop means to conduct a “massive perlustration” of soldiers’ and civilians’ correspondence, with the aim being to measure and reshape public mood.[11] On the whole, the “discovery” of morale implied the adoption of a sort of “system of information” based on surveillance, propaganda and censorship to isolate the front line from the interior, to prevent the dissemination of rumours, and to preserve home front morale; the so-called cultural output was strictly regulated by censorship mechanisms or voluntary self-censorship. In almost every country writers, journalists and intellectuals contributed to the formation of wartime public opinion (or even manipulated the spirits, with the so-called bourrage de crâne or brainwashing). Newspapers published news provided by governments, exalted patriotism, denigrated the enemy and encouraged civilians to participate in the war effort.[12] In addition, during wartime, morale was synonymous with “morality”; censorship was also connected to the “seriousness of the times”, implying control over individual and collective behaviour and entertainment in order to preserve the war effort and the quickly changing societal hierarchies.[13]

Stalemate and the Pressures of War on the Home Fronts↑

In the first half of the war the popular mood in the interior depended on the news about the military operations; therefore it passed through extreme highs and lows. This development also relied on the popular lack of comprehension of the dynamics of trench warfare and was made more complicate by the curtains posed by censorship and propaganda. Defeats were downplayed or censored, the news about the war was inaccurate and therefore led to false news, spy mania, and tales of enemy atrocities which reflected the popular emotions at the outbreak of the war.[14] Indeed, most had to imagine what the war was like. From mid-1915, however, the bloody trench warfare and the impact of material conditions at home became overwhelming. War came home. The losses and the growing conversion of the economic system put further pressure on the home fronts; although not exposed to the threats of the battlefront, people experienced the “other side” of war, such as shortages of food and coal, soaring prices, queues, deprivations, and moral suffering. The war dominated people’s thoughts, especially among the families of frontline soldiers. As war continued, the more direct knowledge of warfare on the one hand depressed the popular mood and on the other hand, augmented resolve. Among the Entente Powers, popular endurance was based on the assumption that the state would provide for combatants and their families; in other countries, the militarization of society (Italy, Tsarist Russia, Central Powers) and the issues of constraint and obedience were more relevant. In particular, the first war strains in 1915-1916 led Russian and Central Powers military commands to establish postal censorship boards to evaluate military correspondence and scrutinize popular mood. Russian authorities compiled reports based on eavesdropping on conversations and summaries that categorized and explained civilians’ mood (“patriotic”, “depressed”, “indifferent”), not only to prevent unrest but also to reshape civilian mood. In Germany, local district commands prepared secret monthly reports (Monatsberichte) on civilian attitudes (Stimmungberichte) and morale (Geist), often using paid informers, military and police officials; in the Habsburg Monarchy the censorship boards categorized public mood by nationalities as there were fears of internal disloyalty.[15] In the same period Italy and France also developed a surveillance system based on the pre-war prefects’ network and censorship boards on military correspondence. In the central phase of the war civilian morale relied on the prospect of a resolutive battle, on the so-called “equality of sacrifices” and on the capacity of patriotic groups to mobilize communities. The duration and the unprecedented intensity of the war augmented the popular perception of a long-lasting war; everyone hoped that war would end in a short time, but these predictions were postponed year after year, increasing the wait on something that would break the stalemate.[16] The growing hardships and the bloody battles of attrition in 1916 with their huge burden of losses without considerable gains affected civilian morale almost everywhere. Winter 1916-1917 marked a general turning point as the first cracks in domestic morale appeared (Italy, Tsarist Russia, Ottoman Empire), accompanied by an increasing deterioration of the social truce (France, Germany) as discouraging rumours brought by soldiers on short leave began to circulate.[17]

The “Impossible” Year: 1917↑

The year 1917 marked a clear break. The military casualties, the tension between the fighting front and the home front, and the globalization of the war, which influenced international trade, contributed to undermine the resolve of warring populations. In this general framework the death of Francis Joseph I, Emperor of Austria (1830-1916), the February and then Bolshevik Revolution in Russia, the United States’ entry into the war and the proposals of peace created an increasing atmosphere of tension.

The Tsarist Russian home front was the first to fall. To some extent the Russian case, albeit unique, summarized the challenges that almost every nation had to face in 1917: military failures, gendered and class war-weariness, economic exhaustion, national/ethnic claims. The discontent erupted simultaneously all around Europe from spring 1917 as the hopes for an early end of the war converged with deteriorating morale in parallel directions in the interior and at the front. The perception of an endless war wore out the patriotic appeals, and popular confidence was replaced by disillusionment and social unrest. The war exacerbated economic tensions and developed a social inequality in the face of death and in economic resources. In fact, on almost every home front, especially in Russia and among Central Powers, the reciprocal “moral” judgments on the contribution to the national effort gave rise to urban-rural strains and class divisions; the common images of the “shirker”, the “peasant hoarder” and the “profiteer” embittered the mood and assumed political dimensions.[18]

In different ways and intensity, women, peasants and workers were the protagonists of popular discontent. In 1917 women first expressed their war-weariness as they were anguished for their husbands on the front line and concerned about daily sustenance of their families. As they felt entitled to new rights through their participation in the war effort, women staged numerous demonstrations, protested against inequalities and advocated peace. The working class as well showed increasing signs of discontent due to the deteriorating conditions in the industrial conurbations.[19] The war-weariness resulted in a huge wave of often spontaneous strikes led by women or socialist activists; the first strikes had a “moral” character, revolving around material issues (wages, food, working conditions) and thus aimed to reaffirm workers’ own identity in front of their employers and the state authorities. In 1917 socialism and the February Revolution in Russia augmented the demands for peace and social reforms.[20]

In the last part of the war the radicalization of social unrest on both sides was augmented by hardships. In fact, the blockade and submarine warfare caused shortages, hunger (Central Powers) and even famine (Ottoman Empire). In particular, shortages combined with war-weariness and lack of political reforms contributed to the emergence of revolutionary or national claims in Germany and Austria-Hungary.[21] The home front morale also declined among the Entente Powers, and the war strains were felt in France (April-November 1917) and especially in Italy (spring-summer 1917), where there was a huge unrest among workers and peasants that culminated in the Turin insurrection (August 1917). The workers’ strikes also pushed the French and British governments to strengthen surveillance. In France, after a first tracking of the Parisian working class during 1916, the prefects provided regular reports on the popular mood, accompanied by monthly military bulletins on local morale produced by “Commissions de contrôle postale”. In Britain, the military staffs, police and Ministry of Munitions established a system of surveillance based on postal and press censorship, counterespionage and political policing.[22]

Enduring the War: Between Remobilization, Revolution, and Longing for Peace↑

The 1917-1918 morale crisis on the home fronts was expressed with an intense longing for peace. In fact, despite state controls and censorship, people were aware of fluctuation in the level of combat from letters and tales of soldiers on short leave. In this period, censorship boards on all sides noted different kinds of “peace” in the correspondence, from peace at “any price” (the so-called “defeatist peace”) to “paix victoriouse”, from “eternal peace” to “revolution for peace”. Indeed, in this period the mood on the front line and home front mirrored each other; there was increasing interaction between military and civilian spheres.[23] In this general framework, morale dwindled and depended on military developments and diplomatic issues; the Central Powers peace attempts, the assertions of Pope Benedict XV (1854-1922) (war as a “useless slaughter”), Woodrow Wilson’s (1856-1924) Fourteen Points or the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk raised hopes and fears. On the whole, the increasing victimization of home fronts engendered popular pacifism based on prophecies, holy apparitions, rumours and false news. Widespread war-weariness and the fear of a socialist revolution pushed governments to remobilize home fronts by reinforcing welfare policies and food distribution, intensifying and coordinating patriotic propaganda, and providing further militarization of societies.[24] The “vocabulary of endurance” (“tenir”, “hold fast”, “durchhalten”, “resistere”) became a common feature on almost every home front. Nonetheless this “second wave” of mobilization entailed the recognition of popular sacrifices and morale, a new explication of war aims and a renegotiation of the terms of their support. Although this effort followed similar patterns, it had different outcomes, from victorious endurance to revolution.

Civilian Morale: National Cases↑

France, Great Britain and Italy↑

The economic and morale mobilization was easier among French and British people as the idea of a righteous war was widespread. In France, the soaring agricultural prices, exchanges of workforce within rural villages and public allowances initially counterbalanced the upheaval caused by conscription. Meanwhile, the industrial mobilisation and state controls were generally accepted in return for adequate distribution of food supplies and collective bargaining agreements.[25] On the local level, elites, mayors, priests, and the middle class promoted relief work, patriotic discourses and models of behaviour for the wartime society (cult of sacrifice and heroism, austerity, mutual solidarity), which followed class, gender, communitarian and even religious lines. In the first half of the war, the civic spirit and the “social relations of sacrifice” contributed to construct new local “imagined communities” which augmented popular commitment and made bereavement bearable.[26] Therefore, in 1915-1916 the opposition to the war was quite marginal in general public opinion, limited to some parts of socialist groups and trade unions.[27] French people did not settle in a “long war”, instead perceiving war as a series of short successive periods (three to six months), depending on the outcomes of battlefront operations. The military setbacks of 1914 led to a decline of morale, whereas the subsequent successes produced renewed patriotic sentiment. French morale collapsed during the short German offensive in April 1915, then rose temporarily with Joseph Joffre’s (1852-1931) offensives in September 1915, fell again during the German attack on Verdun in February-April 1916, and rose in response to French resistance.[28] The great battles of attrition of that year (Verdun, Somme) caused a decline in morale, which remained low into the early winter of 1916-1917.

The British mood followed the same pattern, but at the beginning of 1916 it changed after the introduction of conscription dispelled the voluntary character of popular participation in the war effort.[29] The British government realized that sustaining morale had become an indispensable part of prolonged warfare. This implied a larger use of war propaganda to promote military enlistment and motivate workers. In 1917, the situation worsened and the United States’ entry into the war did not counterbalance the war-weariness. In fact, the British consent showed signs of weakening due to the unrestricted submarine warfare, which determined shortages and exacerbated class tensions; pacifists, socialists and a growing part of the public opinion started to think that it was time to end the war. The crisis also affected the Dominions; in fact, Canadian and Australian unions and rural organisations repeatedly refused to introduce compulsory conscription.[30] The lowest point in British morale was reached in the winter of 1917-1918, when London was targeted by air raids and there were breakdowns in distributions of food supplies.[31]

France also experienced a home front crisis in spring-summer 1917; the deteriorating conditions both on the battlefront and home front caused civilian discontent to emerge. The working class, especially in the Parisian region and in southern France, broke down the union sacrée and went on strike to express its hostility towards the war and worsening living conditions. Many of the strikes and protests were spontaneous and led by women.[32] The crisis reached its peak during summer 1917; in June 1917, almost half of prefectures reported “indifferent” or “poor” morale. While peasants in the countryside became indifferent to the collective war effort because of losses, requisitions and fears of famine,[33] in urban settings pacifist issues (“paix a tout prix”) gained ground in public opinion and joined with revolutionary defeatism which remained a minority. Although during the German spring offensive in 1918 these issues emerged again, the bulk of socialist party members and trade unions remained faithful to the Republique, showing their support for national defence;[34] on the other hand, from late 1917 French President Georges Clemenceau (1841-1929) gave new political legitimacy to the state and left no room for defeatism using concertation, censorship and repression.[35]

Unlike the French and British cases, the war waged by Italy was characterized by mobilisation without consent. As the secret reports of the prefects in April 1915 show, Italian public opinion was not enthusiastic about entering the war; the peasantry was reluctant, the socialists and Catholics were against the conflict, and only urban middle classes supported the intervention to achieve national unity with the “liberation” of the cities Trento and Trieste.[36] Monarchy, military and state apparatus outweighed the population’s wishes and thus society faced uncertainty and repeated crises of demoralization. Moreover, despite the evidence on the nature of trench warfare in Europe, the military campaign was presented as a short one; therefore, when the battlefront became a bloody stalemate there was widespread delusion. Furthermore, the huge losses that occurred in the first five great offensives on the Isonzo front, coupled with authoritarian mobilisation based on the militarization of the industrial workforce and policing, soon depressed civilians’ morale. The mood declined further in 1915-1916 due to the hardships and the temporary defeat on the Asiago plateau in May 1916, and rose again, especially in urban settings, when the Italian army entered the city Gorizia in August 1916. During summer 1916, however, there were large cracks in domestic morale, especially in the countryside, where villages where hard-hit by losses, requisitions, tax burdens, lack of workforce and inadequate medical care. The state was perceived as an “enemy” and the absence of a prospect of victory caused a general discontent to emerge, especially among peasant women who staged numerous demonstrations. The February Revolution had a great impact on the Italian working class, which struggled for better working conditions, dignity and peace.[37]

During spring-summer 1917 civilian morale collapsed; the assertions of the socialist leader Claudio Treves (1869-1933) – who in July 1917 stated publicly that there would not be “another winter” in the trenches – and the following statements of Pope Benedict on the war raised new hopes of peace amongst a war-weary and polarized population; cases of profiteering, the phenomenon of shirkers, disparities of food distribution and the lack of military successes led to numerous peasant demonstrations (around 500 cases) and workers’ strikes that reached their peak with the Turin insurrection. After the Caporetto retreat in October 1917, there was little patriotic reaction among the lower classes, and Italy was close to defeat; peasants protected the deserters and welcomed the arrival of invaders as the end of the unbearable war; with these attitudes not only the war-weariness, but also the rift between state and population were made evident.[38]

Tsarist Russia. The “Peace and Class” Challenge↑

The breakdown of home front morale played an important role especially in Tsarist Russia as the popular discontent in 1917 led to revolution. Although military authorities solicited the control of public opinion, Nicholas II, Emperor of Russia (1868-1918) waged war with little effort to explain its aims, stifled the self-mobilisation of educated elites, and refused to enact political reforms, thus failing to arouse patriotism.[39] The defeats of 1915, with their huge casualty ratio, had a destabilizing effect on morale both among soldiers and civilians; the worsening conditions and the ineffective management of the home front exasperated popular grievances and led to a first wave of strikes in spring and summer 1915, which were repressed. Due to the soaring prices, shortages and inflation, women created social unrest in many towns and rural areas during the middle of the conflict in order to obtain bread and consumption goods.[40] Recent research has shown that the issue of “equality of sacrifices” was important in Russian society as well. The disproportionate distribution of money allowances, bribes, exemptions, abuses of medical commissions and requisitions created a growing distrust of local and central authorities.[41]

In 1916, the crisis deepened due to meagre agricultural production; daily life became more difficult and supplies for urban dwellers and consumption areas were reduced due to interruption of transports and military needs. These circumstances intensified the feeling of injustice and contributed to polarize the Russian society. In the countryside peasant morale declined sharply due to repeated male conscription, huge casualties and the low allowances for agricultural output. Moreover, the land distribution was regarded as unfair and thus peasants “withdrew” from war effort.[42] At the end of 1916, the situation was unbearable as the detachment of peasants contributed to create rural-urban strains and increasing difficulties in rural consumption areas. The “bread” issue ruled home front morale. The authorities’ failed attempts to control supplies and prices augmented the unrest and gave strength to the growing consent of socialists among workers and peasants.

In winter 1916-1917, the Tsarist state’s inability to provide industrial workers in Moscow and Petrograd with adequate sustenance fuelled anger, unrest and strikes, which led to the February Revolution and brought an end to the old regime that lacked legitimacy.[43] The popular expectations of peace, national autonomy and political and economic reforms clashed with the Provisional Government’s decision to keep on waging war and created a divide between authorities and the population.[44] At this stage the “peace” issue and the failure to maintain morale both at home and on the military front were a crucial point for Russian society, which was unable to sustain further war strains. In this framework, women of mobilized men (Soldatki) contributed to the radicalization of protest and overtly expressed their opposition to war; they demanded the return of their husbands, disregarded profiteers, and above all, showed anger against local authorities and propertied elites, who were held responsible for the losses and war strains.[45]

Despite the attempts to shape public opinion, the Provisional Government failed to consider the war-weariness and land hunger that pervaded the peasantry, and therefore the attempts to remobilize society failed. As the government was unable to sustain markets and did not significantly improve workers’ welfare, the strikes radicalized politically; meanwhile, the compulsory grain levy and the failed Kerenskii offensive created internal chaos and the breakdown of home front morale.[46] People followed the “peace, bread and land” issues promoted by the Bolsheviks and during spring-summer 1917 soldiers deserted and peasants started to seize lands; as the crisis deepened, peasants and workers supported the October Revolution that led Russia to withdraw from the war.[47]

Central Powers↑

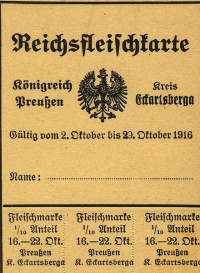

Morale among the Central Powers’ populations was influenced by the militarization of the home front, hardships and lack of political reforms. Due to the blockade, the food issue affected everyday life and, in the long run, changed the relationship between people and institutions. This issue became evident beginning in 1914 and 1915, when the state subordinated home front consumption to military needs. In this stage, while rural communities were able to stabilize, the mood in urban settings was more sensitive due to the rising cost of life and the first shortages. In April 1915, German authorities had to introduce rationing and the following winter, public mood in Berlin and in many German towns worsened due to the demoralizing effect of scarce supplies; this situation represented a sort of first watershed in general public opinion towards the war.[48]

Although the home front endured, German authorities’ inability to create a wartime levelling among classes perpetrated social inequalities that were in turn aggravated by the growing militarization of the home front. The war strains were mostly perceived by urban dwellers and working classes that suffered from exhaustion, shortages, rising food prices and queues. The so-called “turnip winter” of 1916-1917 marked a second important turning point for civilian morale, meanwhile the introduction of the Auxiliary Service Law put further burden over German society and reduced internal cohesion. Monatsberichte (monthly reports) from all over the country described the women as in a “terrible mood”, protesting loudly for food and “peace at any price”.[49] The severity of the situation is demonstrated by the fact that morale also worsened in the countryside, where peasants revealed anger and bitterness at requisitions of food, often carried out without sufficient compensation.[50]

A similar situation occurred in the multi-ethnic empire of Austria-Hungary, where the war strains combined with the weak constitutional rule were translated into ethnic claims. Domestic instability emerged in 1915, when Austria-Hungary lost Galicia. This event depressed the general public mood and fuelled claims for an equality of sacrifices among nationalities. However, the authorities relied on the militarization of the home front, policing and repression.[51] As war dragged on, the mood worsened and supplies declined as well. In May 1916, Vienna experienced hunger riots; censorship boards noted that there was widespread war-weariness (Kriegsmüdigkeit) in the capital and described a socially atomized population, characterized by alienation (Entfremdung) from the state, lack of solidarity (Entsolidarisierung), apathy and gloomy indifference. As occurred in Germany, civilian morale fell during the harsh winter of 1916-1917. In this phase, men and women ceased to be interested in war news or politics. Their letters showed an increasing number of complaints about child malnutrition, illness and the everyday struggle against shortages.[52] In the industrialized conurbations, food riots and strikes became expressions of a kind of hatred against privileged groups. In fact, from May 1917 Austrian censors noticed emerging socialist tendencies even in middle classes and described a violent criticism against rich people and authorities, the latter considered incompetent and indifferent to popular grievances.[53] The Central Powers’ working class discontent erupted and the wave of strikes in many industrial towns (Berlin, Leipzig, Düsseldorf, Hamburg, Vienna) was connected with peace (“without annexations”) and political reforms.

As society polarized, the attempts to remobilize created further divisions. In Germany, General Erich Ludendorff (1865-1937) modernized political communication and tried to use monthly reports to organize a coordinated “enlightenment activity” (Aufklärung Tätigkeit, May-July 1917) to underpin civilian morale through new war aims; the issues of “fortitude” (Durchhalten), “honour” (Ehre), “loyalty to community” (Treue), “cohesion”, “sacrifice” and “struggle” against internal and foreign enemies were central in this propagandistic effort.[54] In addition, in order to crush the political uncertainties, the Vaterlandspartei was created in October 1917. Overall, despite a radicalization of war propaganda and the involvement of churches and patriotic organizations, the permeation of civil society with military values without any reference to political reforms was counterproductive and failed to reach middle and working classes, peasants and women.[55] If the Spring Offensive in 1918 raised hopes of a quick victory, the severe hardships and the following retreat of the army caused a complete breakdown of home front morale. In the same way, in Austria-Hungary, remobilization was influenced by shortages, disillusion and expectations of reforms. After the forced political truce, the attempts of patriotic democratization promoted by Charles I, Emperor of Austria (1887-1922) in 1917 failed as they came too late. In fact, the partial restoration of constitutional rule and civil liberties in order to restore domestic stability and negotiate support of the war effort in exchange for home rule, allowed a sort of “re-politicization” of society. This new political scenario had the opposite effect because it favoured the uncontrolled fragmentation of the public sphere and the dissemination of “unpatriotic agendas” (nationalist claims, socialist and pacifist issues), which garnered increasing consent among a war-weary population. The state propaganda was not up-to-date, was poorly coordinated and did not address social and political problems. In the long run, the discriminatory policy towards national minorities (South Slavs, Czechs, Slovakians), combined with Magyar-Austrian food quarrels, arbitrary repression and Entente Powers’ propaganda, detached large sections of the population from the war effort; in 1917-1918 the widespread food crisis contributed to augment tensions and transformed class-related demands into ethnic claims; even relief work followed ethnic issues. Since the central government could not provide food and peace, national minorities instituted councils, claimed self-rule and thus challenged the emperor’s legitimacy.[56]

The failure of the Austrian government to negotiate immediate peace and the Russian withdrawal from the war augmented labour discontent. In different ways, food riots, rural-urban strains, strikes, desertion and the black market became expressions of distrust in state authorities.[57] The growing disillusionment was also demonstrated by the recourse to the so-called “black market of information”, variably composed of uncontrolled news, rumours, and anonymous writings which – as occurred in Vienna – ended up disrupting social bonds. In this dramatic situation Jews, shirkers, Slavs, farmers, merchants, and even refugees and Italian prisoners of war became the target of popular hatred.[58]

Alongside the military setbacks, the long-term impact of the blockade also contributed to undermine popular commitment; in fact in 1917-18 the issue of shortages – which was connected to the “morale economy” of the masses, and at least, to citizenship and state legitimacy – affected civilians, who experienced a total exhaustion of economic structure.[59] In this perspective, the studies on urban war experience (Freiburg, Berlin, Lepizig, Münster, Düsseldorf, Vienna) have shown that the incapacity to solve the food crisis and to fight against the black market delegitimized authorities, undermined consumers’ morale and ultimately contributed to disintegrate urban communities.

In both countries, military (and often civil) authorities, although aware of the direct connection between the home front and battlefront, did not accord importance to popular war-weariness and considered it a lack of resolve or a result of socialist and defeatist propaganda; generals and the high commands held that it was the rear that had “contaminated” the front, an explanation that in the aftermath of the war gave birth to the “stab in the back” myth.[60] In this general framework, the mobilisations and promises of reforms in the Central Powers did nothing but increase the longing for peace and the expectations of parties and the population still excluded from power.[61] From summer 1918 severe hardships and military defeat provoked vast disillusionment; in south Bavaria, Rhineland, Westphalia and Saxony, in Tirol and in the rural districts of Austria there was a mood of “general depression and hopelessness”. Neither the workers nor large sections of the Mittelstand (middle class) had confidence any longer in the government and all desired a peace of compromise; people criticized military commands and the idea of opposing the government by force was widely accepted, in the towns as well as in the countryside. At the very end of the war, the political views of civilians overlapped with those of the soldiers; the desire for peace at any price was so widespread that the population supported revolutionary issues and claims for national independence.

Lifting Morale: Successful Remobilization↑

In the last phase of the war, civilian morale was at least conceived as a national “resource” and surveillance was increasingly used as a means to adopt new policies and “remobilize” the home front.[62] In this new scenario, the propaganda used in earlier years, especially towards neutral countries, played a greater role on the home fronts. State and private agencies renewed the spirit of national community, intensified the struggle against internal enemies and publicized the war aims with leaflets, newspapers and public meetings. While the Central Powers and the Russian Provisional Government failed at this attempt because of war-weariness and worsening conditions, the Entente Powers, despite great difficulties, were able to reinforce popular commitment for outright military victory.[63] This process also occurred in the United States where propaganda was crucial in conditioning the American public to accept entering the conflict; from April 1917, the U.S. government instituted the “Committee on Public Information”, which encouraged civil society to support mobilization and in addition gradually created a sort of surveillance system with the aim of conscripting men, controlling “enemies within” (pacifists, German-born people) and maintaining the racial order in the South.[64]

Where remobilization was carefully attuned with civilians mood, it was successful; scholarly research on France and Great Britain has shown that the patriotic committees, such as the French Union des Grandes Associations contre la Propagande Ennemie, (March 1917), Commissariat general de l’Information et à la Propagande (November 1917) or the British National War Aims Committee (August 1917), played an important role in intensifying popular support in both rural villages and urban settings. In France, lecturers presented the war in terms of “national survival” and reminded the population that the war’s victorious outcome depended on their continued steadfastness. In addition, emphasizing the rhetoric of collective sacrifice, people were told that any sacrifice they were asked to make was less onerous than the soldiers’. This kind of propaganda reinforced patriotism and contributed to marginalize the dissenters; on the other hand, the popular conviction that this terrible war would be the last one strengthened the will to keep on fighting for the national cause despite mounting casualties and moral suffering.[65] At the same time, in Great Britain, the National War Aims Committee reconfigured patriotic themes – the justice of the British cause, the rhetoric of equal sacrifice, pride, the preservation of values of civilization – in a narrative reflective of the experience of war-weary civilians and tied to traditional values; government officials had to respond to the popular concerns and negotiate with citizens for sacrifices. The adaptation of the messages to the various types of audience and the knowledge of local conditions and attitudes were key components for the success in maintaining civilian morale, resolution and effort.[66] Broadly speaking, remobilization was supported by the amelioration of living conditions; in Britain, for instance, the quick implementation of rationing contributed to keep morale high, meanwhile the Wilsonian principles promoted by propaganda gained increasing support also among the working class, whose unrest, after the climax in November 1917, sharply declined.[67] Where patriotism lacked, as in Italy, the government extended military powers over the northern part of the country in order to prevent working class unrest, created new state agencies (Commissariato per l’assistenza civile e la propaganda), and promoted a large prefect enquiry on the “public spirit” of the population (February 1918), mostly devoted to fighting home front defeatism and socialist activism. Albeit with great difficulties, the aim of defending the national territory invaded after the defeat of Caporetto pulled a war-wearied people to sustain the armies, but this final effort divided society.[68]

Conclusion↑

In November 1918, the longing for peace was so great that winners and losers rejoiced because they did not have to face the war any more. The armistice brought joy and relief, but “fatigue marked the faces of crowds” as there had been “too many wounds, too many losses.”[69] From this perspective the Great War dramatically exalted emotional experiences and caused significant upheaval in terms of cultural and psychological patterns of behavior, from endurance to protest, isolation to participation, adaptation to revolution. Nonetheless, the echoes of Russian events or the Wilsonian principles conveyed high aspirations of a radical change in Europe and the European-dominated areas.[70]

In the aftermath of war, the masses, and consequently public opinion, emerged as a new force in the political and social arena of every nation. On the whole, in such an intense and prolonged war, morale was a key factor. As seen, morale was influenced by hardships, upheavals in labour relations, but also by psychological factors, including war length, nationalism, belief in victory, equality of sacrifice, sense of safety and protection from threats. Maintaining morale depended largely on governments’ ability to manage military operations, allocate resources, bolster public opinion and generate a collective entitlement through social and political reforms. The achievement of this goal implied the prevalence of national aims and emphasized the “us/them” dichotomy, which reinforced ethnic/class divisions and jingoism.

Seen from “below”, morale depended not only on the notion of “equality of sacrifices”, but also on the different degrees of integration of the social groups into the nation. From this point of view, despite oscillations, the middle and upper classes were more confident throughout the war, while the popular mood seemed to be more fragile and dependent on local situations and events. Although a part of the lower classes interpreted the conflict as a duty, the civilian mood seems to be a mixture of endurance, resilience, impotence and anger, in a framework in which there was a lack of alternatives and the repressive measures repressed the dissenting voices. Thus the boundary between belligerence and resignation was so thin that morale and endurance appeared as a sort of delicate and negotiated process.

At the same time, despite cracks in domestic morale, the war continued because victory would mean peace, and because people expected tangible improvements that they had been promised. In the aftermath of war, state authorities, journalists such as Walter Lippmann (1889-1974) or even generals such as Erich Ludendorff recognized the importance of the psychological dimension of war, home front cohesion and propaganda.[71] On the other hand, during the war governments did try to bolster popular morale. In this perspective the First World War marked an important cornerstone for the implementation of vast surveillance projects, which were used as a sort of modern opinion poll to assess the state of civilian morale and shape public opinion; these systems were further developed by totalitarian regimes with the aim of forming whole societies. Indirectly, the rise of “nation security states” reveals not only the governments’ concerns for inner stability, but also “when” states perceived that war became “total” and that it was necessary to gain full control of the home front.

As seen, the “discovery” of civilian morale was also influenced by the different attitudes of populations towards the war and, moreover, by the way states promoted mobilization. Almost every government created “systems of information” based on censorship and propaganda in the initial phase of the war; by 1915-1916 this system was accompanied by the tracking of popular mood. As self-mobilized groups and newspapers lost their effectiveness, states intervened with more refined and coordinated techniques of propaganda.[72]

In sum, one can graphically represent civilian morale with a kind of an irregular (but declining) line: after the general dismay of 1914, morale went up and reached a first plateau in 1915-1916 when the issue of a short war and self-mobilization contributed to keep societies fighting; the harsh winter of 1916-1917 represented a turning point that marked the first breakdown which reflected the war length, deterioration of living conditions and civilians’ better knowledge about the stalemate on the front line. The curve of morale then declined rapidly reaching its lower point in 1917-18, following different issues in relation to the national cases, summer-winter 1917 in Italy, France, Great Britain and Russia, winter 1917-1918 and summer 1918 in the Central Powers. In this phase the second wave of state intervention was successful among the Entente Powers due to relatively fewer strains and shared war aims, meanwhile it failed in the Central Powers and in Russia, where the huge losses combined with the refusal to concede political reforms, the inability to fight social inequalities and the militarization of society undermined civilian morale and delegitimized state authority.

Wartime morale depended on the prospect of victory or on the prospect of ending the war. This perspective made populations accept causalities, but when people understood that the war was unwinnable, the human toll was considered no longer tolerable, as occurred in Russia or the Central Powers after the failure of the offensives in 1918, which were the catalyst to collapse and revolution. While among the Entente Powers the declining morale was expressed through a detachment of some sections of the population (the poorest peasants and, above all, the working class) from the war effort, in Russia and the Central Powers the home front unrest was associated with a political opposition to the war and the ruling classes. In 1917-18, both in these latter states and also in a “winner loser” such as Italy, remobilization tended to increase divisions; governments kept relying on traditional obedience and deference and failed to recognize the sense of citizenship and entitlement that war gave the populace through participation in the war effort; in fact, almost until 1917 they interpreted the spirit of the populace primarily in terms of maintaining the public order. In this perspective the ability to build means to understand the popular mood was not transformed into new policies, because military issues prevailed, authorities failed to act upon what they had “read” or at least because home front grievances were considered a challenge to social hierarchies. One of the most significant lessons to be learned from the First World War was that governments could no longer ignore public opinion when forging new policies.

Matteo Ermacora, University of Venice

Section Editor: Michael Geyer

Notes

- ↑ Winter, Jay: Propaganda and the Mobilization of Consent, in: Strachan, Hew (ed.): The Oxford Illustrated History of the First World War, Oxford 1998, p. 216.

- ↑ Horne, John: Introduction. Mobilizing for “Total War” 1914-1918, in: Horne, John (ed.): State, Society, and Mobilization in Europe during the First World War, Cambridge 1997, p. 5; Horne, John: Public Opinion and Politics, in: Horne, John (ed.): A Companion to World War I, Oxford 2010, pp. 279, 283.

- ↑ Welch, David: Morale, in: Cull, Nicholas / Culbert, David / Welch, David (eds.): Propaganda and Mass Persuasion. A Historical Encyclopedia, 1500 to the Present, Santa Barbara et al. 2003, pp. 252f.

- ↑ Renouvin, Pierre: L’opinion publique en France pendant la Première Guerre mondiale, in: Opinion publique et politique extérieure en Europe. II. 1915-1940, Rome 1984, p. 216. See also: Creel, George: Public Opinion in War Time, in: Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 78 (1918), pp. 185-195.

- ↑ See: Duroselle, Jean-Baptiste (ed.): Colloque sur l’année 1917, in: Revue d'histoire moderne et contemporaine 15/1 (1968); Renouvin, Pierre: L’opinion publique en France pendant la guerre 1914-1918, in: Revue d’histoire diplomatique 4 (1970), pp. 289-336; Becker, Jean-Jacques: 1914. Comment les Français sont entrées dans la guerre, Paris 1977. On the use of surveillance sources, see: Föllmer, Moritz: Surveillance reports, in: Dobson, Miriam / Ziemann, Benjamin (eds.): Reading Primary Sources. The Interpretation of Texts from Nineteenth- and Twentieth-Century History, London et al. 2009, pp. 74-79.

- ↑ Agamben, Giorgio: Stato di eccezione, Turin 2003, p. 7; Holquist, Peter: “Information is the Alpha and Omega of Our Work.” Bolshevik Surveillance in Its Pan-European Context, in: The Journal of Modern History 3 (1997), pp. 415-450; Procacci, Giovanna: Warfare-Welfare. Intervento dello stato e diritti dei cittadini 1915-1918, Rome 2014.

- ↑ For more information on this topic, see Becker, Jean-Jacques: Willingly to War. Public Response to the Outbreak of War, in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War, ed. by Ute Daniel, Peter Gatrell, Oliver Janz, Heather Jones, Jennifer Keene, Alan Kramer, and Bill Nasson, issued by Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin 2015-06-15. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1546333/ie1418.10656. Translated by: Jones, Heather.

- ↑ Gregory, Adrian: A War of Peoples 1914-1919, Oxford 2014, p. 27. See also Mitrović, Andrej: Serbia’s Great War, 1914-1918, West Lafayette 2007, p. 74. Kent, Marian: The Great Powers and the End of the Ottoman Empire, London 1996, pp. 14f.

- ↑ Verhey, Jeffrey: The Spirit of 1914. Militarism, Myth and Mobilization in Germany, Cambridge 2000, pp. 23-27, 65f, 71, 74.

- ↑ Smith, Leonard / Audoin-Rouzeau, Stéphane / Becker, Annette: France and the Great War, 1914-1918, Cambridge 2003, pp. 27f.

- ↑ Holquist, Information 1997, p. 439; Hoffmann, David Loyd: Cultivating the Masses. Modern State Practices and Soviet Socialism, 1914-1939, Ithaca 2011, pp. 183f.

- ↑ Forcade, Olivier: Dans l’oeil de la censure. Voir ou ne pas voir la guerre, in: Prochasson, Christophe / Rasmussen, Anne (eds.): Vrai et faux dans la Grande Guerre, Paris 2004, p. 49.

- ↑ Coetzee, Frank / Shevin-Coetzee, Marylin (eds.): Authority, Identity and the Social History of the Great War, Oxford 1995, pp. ix, x, xii; See also: Le Naour, Jean-Yves: Misères et Tourments de la chair durant la Grande Guerre. Les Moeurs sexuelles des Francais (1914-1918), Paris 2002.

- ↑ For instance see: Pennell, Catriona: “The Germans have landed!” Home Defence and Invasion Fears in the South East of England, August to December 1914, in: Jones, Heather et al. (eds.): Untold War. New Interpretations of the First World War, London 2008, pp. 95-116. About the impact of German atrocities on French public opinion, see: Horne, John / Kramer, Alan: German Atrocities, 1914. A History of Denial, New Haven 2001.

- ↑ Holquist, Peter: Making War, Forging Revolution. Russia’s Continuum of Crisis, 1914-1921, Harvard 2002, pp. 207ff, 212f; Daly, Jonathan: The Watchful State. Security Police and Opposition in Russia, 1906-1917, DeKalb 2004, especially chapter 7; Cornwall, Mark: The Undermining of Austria-Hungary. The Battle for Hearts and Minds, London et al. 2000, pp. 22, 25f.

- ↑ Becker, Jean-Jacques: La France en guerre. 1914-1918. La grande mutation, Brussels 1988, p. 88.

- ↑ Deist, Wilhelm: The German Army, the Authoritarian Nation-State and Total War, in: Horne, State 1997, pp. 162, 164f, 171; See: Cronier, Emmanuelle: Permissionaires dans la Grande Guerre, Paris 2013.

- ↑ Robert, Jean-Louis: The Image of the Profiteer, in: Winter, Jay / Robert, Jean-Louis (eds.): Capital Cities at War. London, Paris, Berlin, 1914-1919, volume I, Cambridge 1997, pp. 104-132.

- ↑ See: Haimson, Leopold / Sapelli, Giulio (eds.): Strikes, Social Conflict and the First World War. An International Perspective, in: Annali della Fondazione Giangiacomo Feltrinelli, Milan 1992.

- ↑ Horne, Public Opinion 2010, p. 284.

- ↑ Becker, Jean-Jacques: 1917 en Europe. L’année impossible, Brussels 1997, p. 87.

- ↑ Millmann, Brock: HMG and the War against Dissent, 1914-18, in: Journal of Contemporary History, 3 (2005), pp. 417, 421, 433ff; Englander, David: Military Intelligence and the Defence of the Realm. The Surveillance of Soldiers and Civilians in Britain during the First World War, in: Bulletin of Society for the Study of Labour History 1 (1987), pp. 24, 28; Becker, Jean-Jacques: The Great War and the French People, New York et al. 1985, pp. 228-232; Flood, P. J.: France 1914-18. Public Opinion and the War Effort, New York 1990, pp. 147, 200.

- ↑ Welch, David: Germany, Propaganda and the Total War, 1914-1918. Sins of Omission, New Jersey 2002, pp. 166, 254; Cornwall, The Undermining 2000, pp. 278, 405; Smith / Audoin-Rouzeau / Becker, France and the Great War 2003, pp. 107, 131ff, 138.

- ↑ See: Horne, Introduction 1997, pp. 1-17.

- ↑ Becker, La France en guerre 1988, pp. 89ff; Flood, France 1990, pp. 79-114.

- ↑ See: Purseigle, Pierre: Violence and Solidarity. Urban Experiences of the First World War (September 2012), issued by Pierre Purseigle, online: http://www.pierrepurseigle.info/violence-and-solidarity-urban-experiences-of-the-first-world-war/ (retrieved: 24 June 2014); Finn, Michael: Local Heroes. War News and the Construction of “Community” in Britain, 1914-18, in: Historical Research 83/221 (2010), pp. 520-538; Miller, Ian Hugh Maclean: Our Glory and Our Grief. Toronto and the Great War, issued by Bibliothèque et Archives Canada, online: http://www.nlc-bnc.ca/obj/s4/f2/dsk1/tape9/PQDD_0015/NQ44830.pdf (retrieved: 30 July 2015).

- ↑ Becker, Great War 1985, pp. 139f.

- ↑ See: Becker, Jean-Jacques: 1914. L’anno che ha cambiato il mondo, Turin 2007, pp. 253, 282-285; Jeanneney, Jean-Noël: L'opinion publique en France pendant la Première Guerre mondiale, in: Opinion publique et politique extérieure en Europe. II. 1915-1940, Rome 1984, pp. 209-227.

- ↑ Monger, David: The National War Aims Committee and British Patriotism during the First World War, PhD Thesis, King’s College, London 2009, p. 29.

- ↑ See: Djebabla, Mourad: “Fight or farm”. Canadian Farmers and the Dilemma of the War Effort in World War I (1914-1918), in: Canadian Military Journal 13/2 (2013), p. 59; For New Zealand, see: Hucker, Graham: The Rural Home Front. A New Zealand Region and the Great War 1914-1926, thesis, Massey University 2006, p. 197.

- ↑ Gregory, Adrian: The Last Great War. British Society and the First World War, Cambridge 2008, pp. 213ff; Coventry, William: The Effect of Zeppelins upon British Morale during the Great War, issued by William W. Coventry, online: http://wcoventry0.tripod.com/id29.htm (retrieved: 15 December 2013); See also: Millman, Brock: Managing Domestic Dissent in First World War Britain, London 2000, pp. 206-209.

- ↑ Bonzon, Thierry / Davis, Belinda: Feeding the Cities, in: Winter / Robert, Capital Cities 1997, pp. 305-341.

- ↑ Hanna, Martha: Spaces of War. Rural France, Fears of Famine, and the Great War, in: Lorcin, Patricia / Brewer, Daniel (eds.): France and Its Spaces of War. Experience, Memory, Image, Basingstoke 2009, pp. 50-54.

- ↑ See: Becker, Les Français 1980, pp. 204-232; Robert, Jean-Louis: Les ouvriers, la patrie, et la révolution. Paris, 1914-1919, Paris 1995.

- ↑ Becker, Great War 1985, pp. 217-235.

- ↑ See: Vigezzi, Brunello: Da Giolitti a Salandra, Florence 1969.

- ↑ Procacci, Giovanna: Dalla rassegnazione alla rivolta. Mentalità e comportamenti popolari nella grande guerra, Rome 1999, pp. 43-145, 205ff.

- ↑ Procacci, Giovanna: L’impatto di Caporetto nell’opinione pubblica italiana, in: Cimpric, Zeljko (ed.): Kobarid Caporetto Karfreit 1917-1997, Kobarid 1998.

- ↑ Smith, Steve: Citizenship and the Russian Nation during World War I, in: Slavic Review 59/2 (2000), pp. 316-329.

- ↑ Alpern Engel, Barbara: Not by Bread Alone. Subsistence Riots in Russia during World War I, in: The Journal of Modern History 69/4 (1997), pp. 696-721; Baker, Mark: Rampaging Soldatki, Cowering Police, Bazaar Riots and Moral Economy. The Social Impact of the Great War in Kharkiv Province, in: Canadian-American Slavic Studies 35 (2001), pp. 137-155.

- ↑ Romanova, Ekaterina: Perceptions of War Burden Sharing in the Russian Society during the First World War (1914 – February 1917), issued by Российская ассоциация историков Первой мировой войны 1914-1918, online: http://rusasww1.ru/view_post.php?id=268 (retrieved: 30 July 2015).

- ↑ Gatrell, Peter: A Whole Empire Walking. Refugees in Russia during World War I, Bloomington 1984, pp. 49-72.

- ↑ Gatrell, Peter: Russia’s First World War. A Social and Economic History, Harlow 2005.

- ↑ Hoffmann, Cultivating the Masses 2011, pp. 193f.

- ↑ Badcock, Sarah: Politics and the People in Revolutionary Russia. A Provincial History, Cambridge 2007, pp. 179ff; Pyle, Emily: Peasant Strategies for Obtaining State Aid. A Study of Petitions during World War I, in: Russian History/Histoire Russe 24 (1997), pp. 41-64.

- ↑ Kroener, Diane / Rosenberg, William: Strikes in Russia. The Impact of Revolution, in: Haimson, Leopold / Tilly, Charles (eds.): Strikes, Wars, and Revolutions in an International Perspective. Strike Waves in the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries, Cambridge 1989, pp. 512, 518.

- ↑ Lohr, Eric: Russia, in: Horne, A Companion 2010, pp. 482, 488f.

- ↑ Deist, German Army 1997, p. 165; Davis, Belinda: Home Fires Burning. Food, Politics and Everyday Life in World War I Berlin, Chapel Hill 2000, p. 97.

- ↑ Carsten, Francis Ludwig: War against War. British and German Radical Movements in the First World War, Berkeley et al. 1982, pp. 42, 76ff, 130-135, 148f; Nübel, Christoph: Die Mobilisierung der Kriegsgesellschaft. Propaganda und Alltag im Ersten Weltkrieg in Münster, Münster 2008.

- ↑ Ziemann, Benjamin: War Experiences in Rural Germany, 1914-1923, Oxford 2007, pp. 142f.

- ↑ Cornwall, Mark: Austria-Hungary and “Yugoslavia”, in: Horne, A Companion 2010, p. 374.

- ↑ Healy, Maureen: Vienna and the Fall of the Habsburg Empire. Total War and Everyday Life in World War I, Cambridge 2004, pp. 122, 136f.

- ↑ Brennan, Christopher: Reforming Austria-Hungary. Beyond His Control or Beyond His Capacity? The Domestic Policies of Emperor Karl I, November 1916-May 1917, London School of Economics, London 2012, pp. 90f, 173, 230f, 285ff.

- ↑ Schmidt, Anne: Belehrung, Propaganda, Vertrauensarbeit. Zum Wandel amtlicher Kommunikationspolitik in Deutschland, 1914-1918, Essen 2006.

- ↑ Deist, German Army 1997, p. 171; Bessel, Richard: Mobilization and Demobilization in Germany, 1916-1919, in: Horne, State 1997, pp. 215, 219f; Deist, Wilhelm: Censorship and Propaganda in Germany during the First World War, in: Becker, Jean-Jacques / Audoin-Rouzeau, Stéphane (eds.): Les societes europeénnes et la guerre de 1914-1918, Paris 1990, pp. 199-210.

- ↑ Cornwall, The Undermining 2000, pp. 18, 25, 30, 284ff, 413; Herwig, H. Holger: The First World War. Germany and Austria-Hungary 1914-1918, London 1997, pp. 274ff, 361-365; Zahra, Tara: Each Nation Only Cares for Its Own. Empire, Nation, and Child Welfare Activism in the Bohemian Lands, 1900–1918, in: The American Historical Review 111/5 (2006), pp. 1378-1402; Ehrenpreis, Petronilla: Kriegs-und Friedensziele im Diskurs. Regierung und deutschsprachige Öffentlichkeit Österreich-Ungarns während des Ersten Weltkriegs, Innsbruck 2005.

- ↑ Roshwald, Aviel: Ethnic Nationalism and the Fall of Empires. Central Europe, Russia and the Middle East, 1914–1923, London et al. 2001, pp. 81-84, 89; Pastor, Peter: Hungary in World War I. The End of Historic Hungary, in: Hungarian Studies Review 28/1-2 (2001), pp. 164-184.

- ↑ Healey, Vienna 2004, pp. 122ff, 145-149; Cornwall, Mark: News, Rumour and the Control of Information in Austria-Hungary, 1914–1918, in: History 77/249 (1992), pp. 52ff; Rauchensteiner, Manfred: Der Erste Weltkrieg und das Ende der Habsburgermonarchie 1914-1918, Wien 2013, p. 79.

- ↑ Offner, Avner: The First World War. An Agrarian Interpretation, Oxford 1989, pp. 25, 57f.

- ↑ Deist, Wilhelm: The Military Collapse of the German Empire. The Reality behind the Stab-in-the-Back Myth, in: War in History 3/2 (1996), pp. 186-207.

- ↑ Sondhaus, Lawrence: World War One. The Global Revolution, Cambridge 2011, p. 377.

- ↑ Forcade, Olivier: Voir et dire la guerre a l’heure de la censure (France 1914-1918), in: Le temps de médias 4 (2005), p. 52.

- ↑ On this issue, see: Horne, John: Remobilizing for “Total War.” France and Britain 1917-1918, in: Horne, State 1997, pp. 189, 198-201, 209.

- ↑ Capozzola, Christopher: Uncle Sam Wants You. World War I and the Making of the Modern American Citizen, New York 2008, pp. 5-8; Keith, Jeannette: Rich Man's War, Poor Man's Fight. Race, Class, and Power in the Rural South during the First World War, Chapel Hill 2004, p. 142; William, Thomas: Unsafe for Democracy. World War I and the U.S. Justice Department’s Covert Campaign to Suppress Dissent, Madison 2008, pp. 110-145; Axelrod, Alan: Selling the Great War. The Making of American Propaganda, New York 2009.

- ↑ Fryszman, Aline: La victoire triste? Espérances, déceptions et commémorations de la victoire dans le département du Puy-de-Dôme en sortie de guerre (1918-1924), Paris 2009, pp. 53-69.

- ↑ Monger, David: Transcending the Nation. Domestic Propaganda and Supranational Patriotism in Britain, 1917-18, in: Paddock, Troy (ed.): World War I and Propaganda, Leiden et al. 2014, pp. 21-24.

- ↑ Gregory, Adrian: Britain and Ireland, in: Horne, A Companion 2010, p. 413.

- ↑ Procacci, Giovanna: “Condizioni dello spirito pubblico nel Regno.” i rapporti del Direttore Generale di Pubblica Sicurezza nel 1918, in: Giovannini, Piero (ed.): Di fronte alla Grande guerra. Militari e civili tra coercizione e rivolta, Ancona 1997, pp. 177-247.

- ↑ Winter, Jay: A Taste of Ashes, in: History Today 48/11 (1998), pp. 8f.

- ↑ Schivelbusch, Wolfgang: The Culture of Defeat. On National Trauma, Mourning, and Recovery, New York 2003; Seipp, Adam: The Ordeal of Peace, Demobilization and the Urban Experience in Britain and Germany, 1917-1921, Farnham-Burlington 2009; Manela, Erez: The Wilsonian Moment. Self-Determination and the International Origins of Anticolonial Nationalism, New York 2007.

- ↑ Lippmann, Walter: Public Opinion, New York 1922; Ludendorff, Erich: Der Totale Krieg, Munich 1935, p. 11.

- ↑ Paddock, Troy: A Call to Arms. Propaganda, Public Opinion, and Newspapers in the Great War, Westport et al. 2004.

Selected Bibliography

- Becker, Jean-Jacques / Audoin-Rouzeau, Stéphane (eds.): Les sociétés européennes et la guerre de 1914-1918. Actes du colloque organisé à Nanterre et à Amiens du 8 au 11 décembre 1988, Nanterre 1990: Publications de l'Université de Nanterre.

- Becker, Jean-Jacques: La France en guerre 1914-1918. La grande mutation, Brussels; Paris 1988: Ed. Complexe.

- Becker, Jean-Jacques: 1914. Comment les Français sont entrés dans la guerre. Contribution à l'étude de l'opinion publique printemps-été 1914, Paris 1977: Presses de la Fondation nationale des sciences politiques.

- Cornwall, Mark: The undermining of Austria-Hungary. The battle for hearts and minds, New York 2000: St. Martin's Press.

- Flood, P. J.: France 1914-1918. Public opinion and the war effort, Basingstoke 1990: Macmillan.

- Gregory, Adrian: The last Great War. British society and the First World War, Cambridge; New York 2008: Cambridge University Press.

- Healy, Maureen: Vienna and the fall of the Habsburg Empire. Total war and everyday life in World War I, Cambridge 2004: Cambridge University Press.

- Hoffmann, David L.: Cultivating the masses. Modern state practices and Soviet socialism, 1914-1939, Ithaca 2011: Cornell University Press.

- Horne, John (ed.): State, society, and mobilization in Europe during the First World War, Cambridge; New York 1997: Cambridge University Press.

- Monger, David: Patriotism and propaganda in First World War Britain. The National War Aims Committee and civilian morale, Liverpool 2012: Liverpool University Press.

- Paddock, Troy R. E.: A call to arms. Propaganda, public opinion, and newspapers in the Great War, Westport 2004: Praeger Publishers.

- Procacci, Giovanna: Dalla rassegnazione alla rivolta. Mentalità e comportamenti popolari nella grande guerra, Rome 1999: Bulzoni.

- Rauchensteiner, Manfried: Der Erste Weltkrieg und das Ende der Habsburgermonarchie 1914-1918, Vienna et al. 2013: Böhlau.

- Verhey, Jeffrey: The spirit of 1914. Militarism, myth and mobilization in Germany, Cambridge; New York 2006: Cambridge University Press.

- Welch, David: Germany, propaganda, and total war, 1914-1918. The sins of omission, New Brunswick 2000: Rutgers University Press.