The Zeppelin Menace↑

In the early months of the war, a number of high-ranking German naval and military personnel were in favour of launching an aerial campaign against Britain. One of the leading advocates, Konteradmiral Paul Behncke (1866-1937), believed that bombing London, its docks, and the Admiralty building in Whitehall would cause panic in the civilian population, which “may possibly render it doubtful that the war can be continued.”[1] Wilhelm II, German Emperor (1859-1941) however, showed a marked reluctance to sanction air raids, particularly on London.

The first bomb to fall on British soil, dropped by a seaplane, landed in Dover on 24 December 1914. The Kaiser, however, only gave his conditional approval for Zeppelin raids (Germany actually used both Zeppelin and Schütte-Lanz airships) to commence on 10 January 1915. London remained excluded as a target until May, with the first raid on the capital taking place on 31 May 1915.

Over the course of 1915 and 1916, German raids reached Britain on fifty-nine occasions (forty-two by airship, seventeen by aeroplane). During this period, airships attacked London eight times, in addition to a raid made by a single aeroplane. On the night of 8/9 September 1915 a Zeppelin attack on the capital caused material damage estimated at £530,000, the most of any single air raid.

Until the summer of 1916 Britain’s defences struggled to offer an effective response. Then, following the introduction of new explosive and incendiary ammunition, the advantage swung in favour of the British pilots: they now had an effective means of igniting the Zeppelin’s hydrogen.

The Switch to Bomber Aircraft↑

In the early hours of 3 September 1916 the first airship shot down over British soil (a Schütte-Lanz, SL.11) crashed in flames in Hertfordshire while attempting to attack London. Within a month the new bullets were responsible for destroying two more intent on bombing the capital, while anti-aircraft guns forced down another. Although the Naval Airship Division retained its faith in airships, only nine raids reached Britain in the last two years of the war. The army, however, abandoned airships and turned to bomber aircraft, which now presented the main threat to London.

The first daylight raid on the capital by Gotha bombers took place on 13 June 1917. It caused 162 deaths and 426 injuries, the most by any single air raid on Britain. Mounting Gotha losses through the summer, however, forced a switch to night bombing in September 1917. Between June 1917 and May 1918 Gotha bombers – joined by the massive R-type Staaken “Giants” (Riesenflugzeug) – attacked London on seventeen occasions and also bombed many south-eastern coastal towns. The last aeroplane raid of the war – aimed at London – occurred on the night of 19/20 May 1918. Zeppelins made one final, futile attack against Britain on the night of 5/6 August.

Effects↑

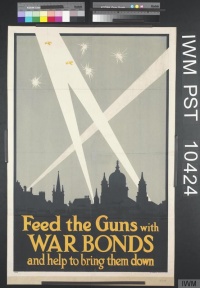

Germany’s aerial campaign against Britain caused 4,743 casualties (1,394 killed and 3,349 injured) of which 2,603 occurred in London (667 killed and 1,936 injured). Estimates of material damage stand at about £2.9 million with around £2.2 million of that inflicted on London. Still, the raids failed to break the morale of the people. In fact, rather than demand the government sue for peace, as Germany had hoped, the raids led civilians to clamour for reprisal raids against German towns and cities. The raids did, however, fulfill some of their aims. War production reduced dramatically before, during, and after these attacks and Home Defence requirements kept large numbers of men, anti-aircraft guns, and searchlights in Britain, along with sixteen valuable squadrons of the Royal Flying Corps (Royal Air Force from April 1918). Britain also gained from the experience. The integrated defence system in place by 1918 formed the basis for that employed successfully when German aircraft returned to British skies in 1940.

Ian Castle, Independent Scholar

Section Editor: Emmanuelle Cronier

Notes

- ↑ Robinson, Douglas H.: The Zeppelin In Combat. A History of the German Naval Airship Division 1912-1918, Atglen 1994, p. 78.

Selected Bibliography

- Castle, Ian: The first Blitz. Bombing London in the First World War, Oxford; New York 2015: Osprey Publishing.

- Cole, Christopher / Cheesman, E. F.: The air defence of Britain 1914-1918, London 1984: Putnam.

- Morris, Joseph: The German air raids on Great Britain, 1914-1918, London 1925: S. Low, Marston & Co.

- Raleigh, Walter / Jones, H. A.: The war in the air. Being the story of the part played in the great war by the Royal Air Force, volume 3, Oxford 1931: Clarendon Press.

- Raleigh, Walter / Jones, H. A.: The war in the air. Being the story of the part played in the great war by the Royal Air Force, volume 5, Oxford 1935: Clarendon Press.

- Robinson, Douglas Hill: The Zeppelin in combat. A history of the German Naval Airship Division, 1912-1918, Atglen 1994: Schiffer Military/Aviation History.