Introduction↑

The First World War was also the "Great War" due to the high number of soldiers taken prisoner during the entire war period. According to some estimates, a total of about 8.5 million combatants became prisoners of war, slightly less than all the soldiers who lost their lives in battle, calculated to be between 9 and 10 million.[1] In fact, out of every nine men mobilized, one experienced captivity. Prisoner-of-war camps were set up throughout the world: in Utah in the United States, Templore in Ireland, Achinsk in Siberia, and Bando in Japan, where the German soldiers captured after the fall of Tsingtau in China were detained. In many cases, the prisoners found themselves having to deal with particularly difficult environmental, food and health conditions. Moreover, many of these men were sent to work to make up for the absence of manpower in all the belligerent nations as a result of the mobilization of the male population called to take up arms. Thus, millions of prisoners of war were forced to work to support the economies of the countries that held them captive.

Italian Prisoners↑

Italian Soldiers Captured and the Number of Deaths↑

According to official estimates, the Italians taken prisoner during the Great War were about 600,000. Half of them fell into the hands of the Austrians and the Germans as a result of the defeat of Caporetto (October 1917). Starting from the data according to which the Italian military force active at the front consisted of 4,200,000 men, it follows that one soldier out of seven was captured.[2] This is a very high number, significantly higher than that recorded in the ranks of the other military contingents that fought on the Western Front - the situation was very different on the Eastern Front, where the conflict was mostly a war of movement and led to a high number of prisoners - which were larger compared to the Italian army and were involved in the conflict for a longer period of time than the troops of Victor Emmanuel III, King of Italy (1869-1947). The German soldiers taken prisoner by France were approximately 393,000; the British captured about 330,000 German combatants; Germany, however, captured 521,000 French soldiers and 176,000 British soldiers.[3]

Equally important is the number of Italian soldiers who died during imprisonment. There were at least 100,000 deaths, 16 percent of the total number of soldiers who ended up in the hands of the Austro-Hungarians and the Germans. According to some estimates, the average incidence of the number of deaths out of the total number of prisoners held in individual nations, should be placed between 2 and 15 percent, reaching 20 percent in Russia and Austria-Hungary. But if, after the war, the rate of losses was of the order of 2-3 percent for the French, British and Belgian prisoners, it increased to 5-6 percent for the Russians, rising to 30 percent in the extreme case of Romanian prisoners of war held in Germany.[4] The causes that led to this dramatic number of deaths among the Italian prisoners can be traced back to the difficult environment in which the prisoners of war generally found themselves – above all because of the delay, on the part of all the nations, in planning the management of a number of individuals that no one had expected to be so massive - aggravated by the decisions taken by the leaders of the military command and the Italian government regarding the fate of their countrymen who ended up in the hands of the enemy nations.

The Suffering of the Prisoners↑

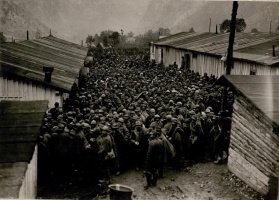

The Italians captured by the armies of the Central Powers were concentrated in just under 500 camps (the largest number of Italian soldiers was held at Mauthausen, in Northern Austria) and, in the case of soldiers from the ranks of the troops, they were forced to do manual work in a few thousand work groups. The descriptions contained in the numerous autobiographical accounts written by prisoners during their period of detention, and above all after their return home, permit one to arrive at an in-depth understanding of the dramatic plight of everyday life that the Italian soldiers had to face in the concentration camps set up in the territories of Austria-Hungary (until the defeat of Caporetto, only 1,000 Italian soldiers were held in Germany). Contrary to the provisions of the International Convention signed at The Hague in 1899 (and reaffirmed in 1907) - that the host countries would have to ensure (at their own expense), that the captured soldiers received treatment equivalent to that accorded to their own troops - as the number of prisoners gradually increased, the Central Powers displayed a growing difficulty in providing a dignified custody for these men. In particular, if for the officers, not subject to forced labour, the treatment, except for in some concentration camps, was acceptable, the condition of the other prisoners suffered progressive deterioration. The Italian officers who died in captivity were 550 out of a total of 19,500 (less than 3 percent) and in a good number of cases their deaths were due to the injuries they had received in their last combat.[5]

The worst fate undoubtedly befell the Italians taken prisoner at the Battle of Caporetto. They arrived in the camps exhausted, after having faced an arduous transfer marked by hunger, harsh physical exertion and decidedly hostile treatment. The winter that they had to face was the one in which the mortality rate recorded in the prison camps reached the highest level: at Mauthausen, in a little more than two months 900 of the 10,000-12,000 prisoners died; at Milowitz, according to an Italian medical officer’s account, about 10,000 Italian soldiers out of a total of 14,000 lost their lives in four months. According to the data contained in an Austrian statistical report and taken up again subsequently in Italy by the Commission of Inquiry on violations of the rights of peoples committed by the enemy, on a sample regarding the causes of the deaths of 500 prisoners, just under 7 percent of the deaths could be attributed to injuries sustained in battle, and only 3-4 percent were attributed to accidents.[6] Other causes of death were correlated with specific diseases such as tuberculosis and cachexia starvation.

Hunger and cold were, therefore, the deadly enemies that Italian soldiers found themselves facing inside the "cities of the dying". The prisoners could count on a daily food supply of less than 1,000 calories, very far from the 3,300 minimum envisaged, by the Allied International Commission, for nutrition in cold places. Those who were forced to work in labour groups far from the prison camps and who often could not be reached by the highly coveted packages from home were in the worst situation. The poor and insufficient nutrition was made even more intolerable by the physical effort expended during working hours, in particular in the coal mines, blast furnaces or in the stone quarries. The situation of those who worked in the countryside and so could try to supplement, in some way, the meagre ration of food granted daily was much better. Within the concentration camp microcosm, hunger, excruciating and merciless, became the measure of all things. In an attempt to counter it, many soldiers decided to sell their valuables and even their heaviest clothes, in order to be able to scrape together a bit of money and get some pieces of bread, but in doing so they exposed themselves even more to the harshness of the bad weather.

The Italian Ruling Class Confronted by the Condition of its own Prisoners↑

When, as a result of the economic blockade, the Central Powers declared their inability to provide for the nutrition of the by then huge mass of enemy soldiers "detained" within their territories, France, England, Belgium and, later, the United States decided – after having overcome some initial misgivings - to intervene by organizing collective aid funded by the state and put into practice through the sending of wagonloads of food, medicine and clothing for their own soldiers held in captivity. On the contrary, the Italian government, although it was promptly informed of the bad conditions in which its soldiers found themselves in Austrian and German prison camps, stubbornly refused to help them, denying any form of state aid. This was an attitude formally justified by the belief that food supplies sent to the prisoners would run the risk of not reaching their destination and ending up in the hands of the Austrian civilian population, but was in fact derived from a calculation of clear political cynicism and an attempt by the High Command to ascribe, to these prisoners, the responsibility for its own failures in terms of military strategy. Starting from the belief that the majority of those who were captured were actually traitors who had voluntarily consigned themselves to the enemy to escape the dangers of the trenches, their suffering, made widely known among the ranks of the combatants of the Royal Army, was used as a possible deterrent against any temptation to surrender. In reality, the flight to enemy lines by groups of soldiers was rather limited; very often the soldiers’ surrender was inevitable, caused mostly by wrong assault tactics and the absence of adequate defensive structures. In fact, for the Italian prisoners, the only hope of survival was linked to the arrival of much coveted parcels containing food and clothing, from families and welfare associations. It should, however, be noted that, in the absence of a centralized, well-structured organization managed directly by the state authorities, the path of the parcels turned out to be very difficult and many of them did not reach their destination or only arrived in the hands of the prisoners after many days, when their content was no longer edible. In the period immediately following the end of the conflict, there were still 1.5 million parcels in Sigmundsherberg (Lower Austria) and 72,000 were in storage in Csòt bei Papa, Hungary.[7]

A partial correction of this policy was only adopted in favour of officers, who were thus able to get collective aid, funded by their families but managed directly by the International Red Cross, which monitored the actual arrival of this aid at the destination. This concession helped to exacerbate the existing differences in treatment between prisoners from the ranks of the troops and prisoners belonging to the officer corps.

In the aftermath of the events of Caporetto, the widespread hostility of the political and military establishment towards the prisoners was once again very evident in the intentions of the Foreign Minister, Sidney Sonnino (1847-1922), who ordered the reduction of the amount of food in parcels addressed to Italian soldiers who were prisoners in Austria and temporarily banned the sending of relief for those who were held in Germany, explaining this decision with the fact that there were no formal agreements on this issue between the Italian and German governments.

It was only in the summer of 1918 - under pressure from international public opinion, which openly defined the Italian government’s conduct towards its military, in the hands of the Central Powers, as scandalous - that the Prime Minister, Vittorio Emanuele Orlando (1860-1952), gave his assent to sending, at state expense, but in a completely experimental way, some wagons of crackers, many of which, ironically, only reached their destination after the conclusion of the conflict. Thus it was a belated and clumsily conducted initiative that represented only a forced suspension of a policy hostile to the prisoners, and which did not change, even after the victory of Vittorio Veneto (24 October - 4 November 1918). In the months after the armistice, in fact, the Italian soldiers who had survived the hardships suffered in the prison camps, once they had crossed the national frontier, were temporarily interned in specific camps, where they were kept in quarantine and subjected - in the guise of alleged "traitors" or "subversives" – to interrogation and possible prosecution.

Subsequently, the memory of what had happened to the 600,000 Italian prisoners was quickly put aside. It was a sort of damnatio memoriae, which was certainly due to the usual difficulties with which all nations recount and celebrate war imprisonment, generally devoid of heroic moments and medals to be awarded for valour, but was also, above all, due to the will of the political and military class of the age which wanted a quick end to having to deal with that page of history, in order to cover up its serious responsibility for the great suffering endured by such a large number of men.

The Prisoners of the Italians↑

Foreign Soldiers Captured and the Number of Deaths↑

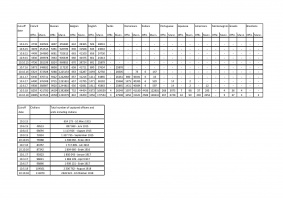

According to official figures, 477,024 enemy soldiers ended up in the hands of the Italians throughout the conflict, a number which includes those who were returned (17,633), those who were enlisted in the armed units that were sent back to the front to fight against the Austrian army (89,760, mostly Bohemians, Slovaks, Poles and Romanians), and those who were freed (12,238).[8] Overall, 18,049 prisoners died. Considering that, presumably, death struck most of the prisoners before the end of the war, and one therefore subtracts the number of those who were captured (about 300,000) during the battle of Vittorio Veneto,[9] from the total number of prisoners, the resulting percentage of deaths is 10.2 percent (18,049 out of about 177,000). This is a significantly lower percentage than that recorded in the ranks of the Italian prisoners, but much higher than that observed for the British and French prisoners.

Points of Concentration and the Work of the Prisoners↑

The first place designated for the confinement of prisoners that was prepared in Italy, was the citadel of Alessandria (Piedmont), a fortress built in the first half of the 18th century. During the first months of the war, as in the other countries which went to war in the summer of 1914, the Italian government decided to allocate existing structures for the concentration of prisoners, such as castles, old prisons, convents, fortresses etc. (the medieval fortress of Santa Barbara in Pistoia, Fort Sperone, Fort Ratti and Fort Begatto in Genoa, the Charterhouse of San Lorenzo a Padula, Naples, the Castello Sforzesco in Novara and so on). Only later, when the inadequacy of these places for the purpose of mass detention had been ascertained, were new prison camps frantically built, consisting of barracks of stone or wood, like the biggest ones, such as those of Santa Maria Capua Vetere (near Naples) and Avezzano (in the province of L'Aquila), but also real "cities of tents", as occurred on the small island of Asinara, north of Sardinia.

Regarding the distribution of prisoners within the individual places of internment in the peninsula, the only information available refers to the 79,978 foreign soldiers (1965 officers and aspiring cadets and 78,013 soldiers) held in Italy in January 1917. Distributed in eighty-one camps, most of these prisoners were stationed in the centre (30,731) and the south (32,960) of the peninsula (there were no prison camps in the whole area of the north east, declared a war zone). After the camp of Padula (Vallodiano), in the province of Naples, where 13,138 soldiers were detained, the island of Asinara, with 11,003 prisoners, was the second largest Italian camp in terms of the number of prisoners. The camps of Avezzano (in Abruzzo) and Santa Maria Capua Vetere (near Naples) followed, with 6,814 and 4,983 prisoners respectively.[10]

Also, regarding Italy, the living conditions in the camps were not the same everywhere and in every period of the conflict. And, of course, among the ranks of the Austro-Hungarian prisoners, the situation of the officers was also - for the same reasons as seen in the case of the Italian prisoners - significantly better than that of fellow soldiers from the ranks of the troops. The camp of Avezzano, built in 1916 on the ruins of the earthquake that had struck the city of Abruzzese in January of the preceding year, was able to accommodate up to 15,000 prisoners (more than 1,000 security guards) and was considered by many observers, a model camp. It consisted of thirty-three hectares, completely fenced-in, within which the barracks for the prisoners covered an area of 40,000 square metres. There were 20,000 square metres of other structures for services, and the water supply was guaranteed by twelve kilometres of pipes and three reserve tanks with a capacity of 1,000 cubic metres each.[11] Things were very different on the island of Asinara where, between December 1915 and January 1916, a huge prison camp was set up (destined to become, after the battle of Caporetto, the largest concentration area for foreign soldiers). Prisoners who were not officers found themselves, for the duration of the war period, in particularly harsh conditions, forced to stay in hundreds of tents which provided, especially in winter, a very precarious shelter for a number of men far greater to that which they were intended to hold, and to deal with a chronic shortage of food and even drinking water. The latter had to be imported by sea from Sardinia, as the springs on the small “devil’s” island were unable to meet the needs of such a large number of individuals. As for the living conditions inside the other prison camps set up on the peninsula, the Austrian and Hungarian autobiographical accounts collected so far are too few to be able to allow an attempt to define a broader framework of information about the fate of the foreign soldiers detained in Italy.

In the case of foreign prisoners held in Italy, the decision to use them in work outside the camps was only taken in the spring of 1916, twelve months after the entry into the war. On 25 May of that year, the Ministry of Agriculture, Industry and Commerce sent the prefects a circular signed by the Minister Giannetto Cavasola (1840-1922), which contained the rules agreed on with the Commission for the Prisoners of War, regarding the use of prisoners in agricultural and industrial jobs to be carried out on behalf of private and public bodies. This use of the prisoners was regarded as an exceptional occurrence and was subject to the strict condition of never entering into competition with the national workforce. The first to get involved were the landowners, who were interested in the prisoners’ manpower to cope with the forthcoming work of harvesting. To meet their demands, thirty-two companies consisting of 200 prisoners each, a total, therefore, of 6,400 men, were formed and deployed throughout the whole country. In the following months, especially after the first weeks of 1917, throughout Italy, the requests for the use of prisoners in the most varied tasks increased.

About 80,000 prisoners, divided into 2,000 detachments, were sent to work in the countryside, mines, factories and to build roads. Subsequently, a circular from General Paolo Spingardi (1845-1918), Chairman of the Military Commission for Prisoners of War, indicated that the number of prisoners working in those circumstances was as a little less than 130,000. 60,000 were used in agriculture, 30,000 for the fuel sector, 7,000 prisoners were used in road, construction and railway works, 2,300 in reforestation and 2,000 in the mines. The State Railways were entrusted with over 2,000 men, while with regard to industry, it appears to be significant that over 1,000 prisoners were conceded to Ansaldo, the large engineering company in Genoa, which was one of the nerve centres of the whole productive system put at the service of the apparatus of war.[12] Accounts from those prisoners obliged to do forced labour are extremely rare. The fact that the few subjective sources, hitherto traced, about the prisoners of war in Italy are mostly the work of officers - who were excluded from work - has so far made it difficult to trace direct accounts related to this issue. It is, however, certain that the Austrian prisoners sent to work in Albania under the control of the Italian military authorities found themselves having to deal with a particularly hostile situation, in which the harsh environmental conditions were made even more unbearable by the local population’s attitude of contempt towards the prisoners.

The Damned of Asinara↑

One particular episode that deserves to be mentioned concerns the tens of thousands of Austro-Hungarian prisoners who, at the end of 1915, were transferred from Serbia to the island of Asinara in Italy. This is one of the most dramatic pages in the history of imprisonment in World War I and in it one finds two of the above-mentioned elements, intertwined. On the one hand, the lack of preparation and the many logistical and organizational difficulties which the individual state authorities had to face in managing the custody of such a large number of men, and on the other hand the political cynicism which part of the Italian governing class then showed in dealing with the fate of the soldiers taken prisoner, in this case within the Kingdom of Italy.

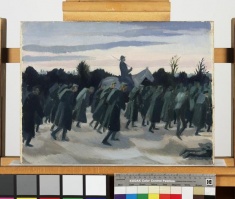

In October 1915, German and Austro-Hungarian troops from the north and Bulgarian troops from the east attacked and invaded Serbia. The Serbian army was forced to escape to the Principality of Montenegro, towards Albania and the sea, dragging in its wake tens of thousands of civilians, who had become refugees, and Austro-Hungarian prisoners, whose number ranged between 35,000 and 40,000 men.[13] An interminable, exhausting march, along the roads and snowy mountain paths from Niš to Vlorë, during which an enormous numbers of prisoners died, worn out by hunger, cold and cholera. In Vlorë – an Albanian city at that time under the control of an Italian military contingent – there were only 24,000 survivors among the prisoners. According to the initial intentions of the Serbian government, these prisoners should have been transferred to France. This proposal was thwarted by the diplomatic intervention of the Italian government, in particular by the above-mentioned Foreign Minister, Sidney Sonnino, who was determined to detain those prisoners in Italy, who were soldiers belonging to hated Austria, and who could have been a valuable pool of labour, able to counterbalance the high number of young Italians called to the front.

Of the 24,000 prisoners who embarked at the port of Vlorë, more than 7,000 died during the transfer to Italy or during the first weeks of their detention on the Italian island of Asinara – an island devoid of appropriate facilities and on which, as has been mentioned, there was a lack of drinking water - where the Italian military authorities organized an unsuitable prison camp. So there were at least 24,000 victims of this terrible ordeal. The responsibility for their deaths lies on the shoulders of the highest Serbian and Italian military and institutional authorities. During the retreat, which soon became a disorderly escape from the territories invaded by enemy armies, the Serbian government and the General Staff of the Serbian army pushed the Austro-Hungarian prisoners forward, forcing them to work in absolutely impossible conditions to make the roads passable. In addition to hunger and cold, the Serb military also furiously attacked these prisoners with often gratuitous abuse and violence, which they justified with the violence that these Austrian combatants had inflicted on Serb civilians during the unsuccessful advances in the summer of 1914.

For his part, the Italian minister Sidney Sonnino confirmed, in that situation, that he was a cynical politician, constantly inclined to favour the national interest in any context. He repeatedly denied France custody of some of the prisoners - despite the news from Asinara which revealed the inability of the Italian health services to cope with the care of those unfortunate men. In fact, Sonnino decreed the death of thousands of them. This choice is even more absurd if one takes into account the fact that, a few months later, in June 1916, the Italian government decided to accede to the new requests of the government in Paris, permitting the 16,000 survivors of the ordeal described above to leave for France.

Conclusion↑

For a long time, the dramatic story of Italian prisoners of war was relegated to the shadows both in terms of collective memory, and of historical research. The great and widespread difficulty with which the different prison-of-war experiences are generally remembered by the country, the armed forces and the veterans themselves is well known. But the cause of the silence which enveloped the stories of these men should also be traced back to the bad conscience of the Italian political and military authorities, who wanted to ensure that those events would be quickly forgotten, in order to conceal their serious responsibility for the great suffering endured by these individuals. As mentioned above, the disappearance of the 100,000 Italian soldiers who died in prison camps organized by Germany and Austria-Hungary was also determined by the behaviour of the government and the Italian High Command (above all of the minister Sonnino and General Cadorna), who, with respect to the difficulties in feeding the prisoners revealed by the countries holding them, refused to send vital aid to those who were suspected of being perhaps traitors or cowards and, in any case, bad models for the many other desperate soldiers who were still in the trenches, exposed to the temptation of saving their lives by deserting. On the other side, that of the Austro-Hungarian and German combatants who ended up in Italian prison camps, the results of the few studies conducted so far by Italian historians do not allow a wide range of knowledge, especially with regard to the living conditions in individual camps. The few cases studied, show, so to speak, light and shadow, giving us, however, with reference to the sad fate of the "Damned of Asinara", one of the most dramatic pages in the history of the First World War.

Luca Gorgolini, Università degli studi della Repubblica di San Marino

Section Editor: Nicola Labanca

Translator: Noor Giovanni Mazhar

Notes

- ↑ Jones, Heather: A Missing Paradigm? Military Captivity and the Prisoner of War 1914-18, in Stibbe, Matthew (ed.): Captivity, Forced Labour and Forced Migration in Europe during the First World War, New York 2009, pp. 19-48.

- ↑ Procacci, Giovanna: Soldati e prigionieri italiani nella Grande guerra. Con una raccolta di lettere inedite, Turin 2000, p. 168.

- ↑ Jones, A Missing Paradigm?, in Stibbe (ed.), Captivity, Forced Labour and Forced Migration 2009, pp. 19-48.

- ↑ Hinz, Uta: Prigionieri, in Audoin-Rouzeau, Stéphane/Becker, Jean-Jacques /Gibelli, Antonio (Italian edition) (eds.): La prima guerra mondiale, vol. I, Turin 2007 (French edition 2004), pp. 353-354.

- ↑ Procacci, Giovanna: I prigionieri italiani, in Audoin-Rouzeau/ Becker/Gibelli (eds.): La prima guerra mondiale 2007, pp. 361-362.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 368.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 363.

- ↑ Tortato, Alessandro: La prigionia di guerra in Italia. 1915-1919, Milan 2004, pp. 49-50.

- ↑ Tortato, Alessandro: Prigionieri degli italiani, in Isnenghi, Mario/Ceschin, Daniele (eds.): Gli italiani in guerra. Conflitti, identità, memorie, dal Risorgimento ai nostri giorni, vol. III, tome 2, La Grande Guerra: dall’intervento alla "vittoria mutilata", Turin 2008, p. 253.

- ↑ Tortato, La prigionia di guerra in Italia 2004, pp. 30-33.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 35.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 108.

- ↑ The data contained in this paragraph comes from Gorgolini, Luca: I dannati dell’Asinara. L’odissea dei prigionieri austro-ungarici nella Prima guerra mondiale, Turin 2011.

Selected Bibliography

- Gorgolini, Luca: Kriegsgefangenschaft auf Asinara. Österreichisch-ungarische Soldaten des Ersten Weltkriegs in italienischem Gewahrsam, Innsbruck 2012: Wagner.

- Gorgolini, Luca: Prokleti sa Azinare (Captivity on Asinara), Novi Sad 2014: Prometej.

- Gorgolini, Luca: I dannati dell'Asinara. L'odissea dei prigionieri austro-ungarici nella Prima Guerra mondiale, Turin 2011: UTET Libreria.

- Hinz, Uta: Prisoners of war, in: Hirschfeld, Gerhard / Krumeich, Gerd / Renz, Irina (eds.): Brill's encyclopedia of the First World War, volume 2, Leiden 2012: Koninklijke Brill NV, pp. 829-834.

- Hinz, Uta: Prigionieri, in: Audoin-Rouzeau, Stéphane / Becker, Jean-Jacques / Gibelli, Antonio (eds.): La prima guerra mondiale, volume 1, Turin 2007: Einaudi, pp. 352-360.

- Pavan, Camillo: I prigionieri italiani dopo Caporetto, Treviso 2001.

- Pozzato, Paolo: Prigionieri italiani, in: Isnenghi, Mario / Ceschin, Daniele (eds.): Gli italiani in guerra. Conflitti, identità, memorie dal Risorgimento ai nostri giorni, volume 2, Turin 2008: UTET, pp. 245-252.

- Procacci, Giovanna: I prigionieri italiani, in: Audoin-Rouzeau, Stéphane / Becker, Jean-Jacques / Gibelli, Antonio (eds.): La prima guerra mondiale, volume 1, Turin 2007: Einaudi, pp. 361-373.

- Procacci, Giovanna: Soldati e prigionieri italiani nella Grande Guerra. Con una raccolta di lettere inedite, Rome 1993: Editori riuniti.

- Reale Commissione d'inchiesta sulle violazioni del diritto delle genti commesse dal nemico (ed.): Trattamento dei prigionieri di guerra e degli internati civili, Milan; Rome 1919: Bestetti & Tumminelli.

- Spitzer, Leo: Lettere di prigionieri di guerra italiani, 1915-1918, Turin 1976: P. Boringhieri.

- Stibbe, Matthew (ed.): Captivity, forced labour and forced migration in Europe during the First World War, London; New York 2009: Routledge.

- Tortato, Alessandro: Prigionieri degli italiani, in: Isnenghi, Mario / Ceschin, Daniele (eds.): Gli italiani in guerra. Conflitti, identità, memorie dal Risorgimento ai nostri giorni, volume 2, Turin 2008: UTET, pp. 253-259.

- Tortato, Alessandro: La prigionia di guerra in Italia, 1915-1919, Milan 2004: Mursia.