Preliminaries↑

The Picardy region in France was a theatre of war from 1914 to 1918. Fighting was concentrated on the Thiepval Ridge north of and the Santerre Plain south of a bend in the Somme and west of the market town of Péronne. The best remembered and most notorious of these battles is the 1916 Battle of the Somme, a 141-day battle of attrition in which Britain’s New Armies suffered greatly.

Fighting occurred near the Somme in the first month of the war. On 26 August 1914 a French reserve corps was surprised and routed at Moislans as the German army swept through northern France, pushing as far as Amiens. In October, during the “race to the sea”, trench lines were established along the Somme. In 1915, after a French attack at Serre, the German defences were heavily strengthened. It was these positions that the British army, which relieved the French north of the Somme in summer 1915, later attacked.

The 1916 Battle of the Somme↑

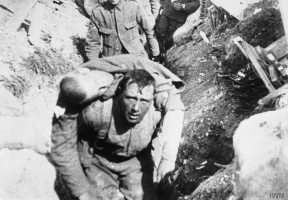

The Battle of the Somme was the Anglo-French contribution to the general Allied offensive during the 1916 campaign, whose objective was to overstretch and wear down the Central Powers’ armies. After the French army was engaged at Verdun, the offensive shrank in ambition, as did the French army’s contribution, leaving the British to take the principal role in the attack on 1 July 1916. British training, however, was far from complete, and British planning was also confused. The operational goals set by the commander-in-chief, Sir Douglas Haig (1861-1928), were overly ambitious and the commander of the Fourth Army, Sir Henry Rawlinson (1864-1925), was unable to mount a sufficiently powerful preliminary bombardment to defeat the strong German defences. The British infantry offensive was preceded by a week-long artillery bombardment in which 1,537 tubes fired more than 1.5 million shells, in the expectation that these would destroy the German fortifications, incapacitate the defenders, and cut the barbed wire in front of the German lines. However, in many places the shelling was not successful, for the guns were too thinly spread along the twenty-kilometre front, and many of the British shells were defective. The outcome was disaster for much of the initial British assault – and some 57,000 casualties – although it was not simply bad planning and weak bombardment alone, but also poor tactics from inexperienced commanders and soldiers, as well as an effective German defence that checked the British assault on the northern sector of their front. In spite of the British losses, the first day’s assault was on the whole successful when the overwhelming success in the French sector is factored in. General Marie-Émile Fayolle’s (1852-1928) Sixth Army employed more effective artillery-centred tactics and took its objectives with 1,600 casualties. This heavy blow to the German army had to be followed up. Thereafter General Ferdinand Foch (1851-1929) took on the task of coordinating French and British operations while the British army developed tactical skills.

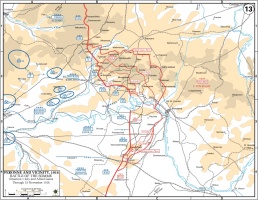

After the initial assault the Somme offensive passed through four phases. In early July, before the German defence consolidated, there was a short period during which the British and French armies made significant forward progress. The French occupied the Flaucourt Plateau, strategic high ground south of the river, which enabled them to enfilade the German positions to the north with artillery fire. On 14 July in a surprise night attack the British seized the second German defensive position on the southern edge of the Thiepval Ridge but could not carry the whole plateau. In the second attritional phase of the offensive, from late July until September, the British found themselves contained in a natural amphitheatre atop the plateau. The Martinpuich, Ginchy and Guillemont villages, and High Wood and Delville Wood formed defensive bastions against which British units flung themselves in a series of localised and generally ineffective attacks that wore down the manpower of both sides. To the north General Hubert Gough’s (1870-1963) Reserve (Fifth) Army was fighting to occupy the Pozières heights east of Thiepval, while to the south Sixth Army advanced across the bluffs north of the river.

In September Foch was able to organise a renewed, powerful and concerted offensive, using four armies to strike successive blows against the weakened German defence. Another French army, General Alfred Micheler’s (1861-1931) Tenth, then extended the offensive south of the river on 4 September. Sixth Army renewed its advance north of the river, breaking through the German third line at Bouchavesnes on 12 September, before Fourth Army renewed its assault in strength on 15 September. In the Battle of Flers-Courcelette – famous for the first (and generally ineffective) employment of the tank, in essence a slowly moving mobile gun-platform – Fourth Army finally cleared the Thiepval Ridge and advanced beyond it, only to face another line of German defences on the high ground beyond. In late September the British were somewhat successful in attacking these German defences during the Battle of Morval. To the north, Reserve Army finally captured the defensive bastion at Thiepval on 26 September using a highly concentrated bombardment coordinated with novel infantry assault tactics. Although this success demonstrated how far British offensive techniques had improved since 1 July, when the defences at Thiepval had defied all assaults, it came too late to affect the outcome of the 1916 campaign. In its final phase in October and early November after the autumn rains came, the Anglo-French assault degenerated into intermittent localised attacks on village strong points. Reserve Army achieved one final triumph, capturing Beaumont Hamel village, which had not succumbed to the British assault on 1 July, in the Battle of the Ancre in mid-November.

This mud-clogged anti-climax, as much as the disaster on the first day, has come to epitomise the Somme offensive. Although it did not decide the war in 1916, it shifted the fortunes of an industrialised war of attrition in the Allies’ favour. The German army suffered heavily, sustaining losses it could not afford. It probably lost more than 500,000 casualties on top of those suffered at Verdun (the numbers are still disputed) and suffered a serious crisis of morale. The British suffered 420,000 and the French 202,000 casualties. The battle gave Allied leaders confidence that they now had the tactics and operational methods with which, in time, they could defeat the German army. It also gave their troops the confidence that they could do so. Fighting on the Somme continued on a reduced scale over the winter before the German army made a spring withdrawal to the new Hindenburg Line defensive position, testimony to their unwillingness to endure another Materialschlacht in 1917. The Australian Corps’ entry into Bapaume on 17 March 1917, an objective of the first phase of the offensive in July 1916, marked the real end to the Battle of the Somme. The Germans conceded the field, and for the rest of 1917 the belief that they could win the war on land.

The 1918 Battles↑

In spring 1918 fighting returned to the Somme. In late March Fifth Army retreated across the old Somme battlefields, pursued by the Germans. The wasteland of 1916 had reverted to nature, but remained a serious obstacle that slowed the German advance. The lines reformed on the heights at Villers-Bretonneux, where Australian and French forces defied all German attempts to push on to the rail junction at Amiens. This was the starting point for the first operation of Foch’s strategic offensive that would end the land war in France, the 8–11 August Battle of Amiens-Montdidier in which Anglo-French forces disengaged Amiens by clearing the Santerre Plain. British Third Army recrossed the old Somme battlefield in late August 1918. By now it was no obstacle to skilled troops with ample munitions: the “winter line” defences between Bapaume and Péronne, which the Germans had expected to hold, were stormed in a matter of days.

Aftermath↑

The 1916 Somme offensive was Britain’s most costly and remains its most notorious First World War battle, while the French army’s major role and relative success in the offensive has been all but forgotten. The opening of the Somme offensive is central to Britain’s “lions led by donkeys” mythology of the war, with the broader strategic impact of the 140-day attritional offensive on the strategic balance of the war largely forgotten. For France and Germany the Somme has less resonance because the ten-month struggle at Verdun symbolizes the war of attrition. Verdun predominates in German memory largely because it began as a successful German offensive, while the Somme was a gruelling defensive battle. The memory of Verdun better suits the mythology of German heroism, and rose to prominence after 1945 as an instrument of Franco-German reconciliation.

The Thiepval Ridge and its environs remain a site of pilgrimage for Commonwealth nations, an evolving landscape of memory and commemoration. At the ridge’s high point stands the Thiepval Memorial to the missing of the Somme, the only Anglo-French commemorative memorial and a lasting tribute to the shared effort and sacrifice in Picardy.

William Philpott, King’s College London

Section Editor: Catriona Pennell

Selected Bibliography

- Brown, Malcolm: The Imperial War Museum book of the Somme, London 1996: Sidgwick & Jackson.

- Dyer, Geoff: The missing of the Somme, London 1994: Penguin.

- Gliddon, Gerald: Somme 1916. A battlefield companion (2 ed.), Stroud 2006: Sutton.

- Philpott, William: Bloody victory. The sacrifice on the Somme and the making of the twentieth century, London 2009: Little, Brown.

- Prior, Robin / Wilson, Trevor: The Somme, New Haven 2005: Yale University Press.

- Sheffield, Gary D.: The Somme, London 2003: Cassell.

- Sheldon, Jack: The German army on the Somme, 1914-1916, Barnsley 2005: Pen & Sword Military.