Background↑

President Woodrow Wilson (1856-1924) signed the Selective Service Act into law on 18 May 1917. It authorized the federal government to expand the armed forces through conscription following the United States’ declaration of war on Germany. At the time of the U.S. entry into World War I, the regular army consisted of 127,000 active duty soldiers along with 181,000 reservists in the National Guard, a force wholly inadequate to decisively influence the strategic outcome of the war in Europe. The total force raised by the end of the war numbered 4,412,533 men, including 3,893,340 soldiers, 462,229 sailors, 54,690 marines, and 2,294 Coast Guard troops. Of the 3,893,340 soldiers, 2,810,296 – some 72 percent – had been conscripted under the Selective Service Act.[1]

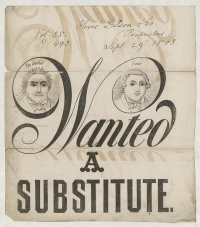

1917 marked the first time since the American Civil War that the federal government mandated a national draft. While many Western European countries regarded universal conscription as a civic duty and a cornerstone of democratic society, many Americans viewed compulsory military service as an infringement on their civil liberties. The Civil War era draft had been immensely unpopular with the American public. Its most controversial provision allowed draftees to opt out of performing military service by hiring a substitute, a caveat that overwhelmingly benefitted the wealthy. Moreover, the draft had been administered by army officers operating under a quota system, an arrangement known to have encouraged corruption and the coercion of volunteers. Opposition to the draft provoked four days of rioting in New York City in 1863 and resulted in repeated incidents of physical violence against federal officials. The controversial legacy of the Civil War draft reinforced Americans’ distrust of state power and contributed to the continued U.S. reliance on a small, professional army backed by state militias for national defense.

Implementation↑

President Wilson initially sought to avoid imposing a draft and proposed to raise a volunteer force of 1 million men. It was clear that this plan had failed, however, when six weeks later only 73,000 men had volunteered. A plan put forward by former president Theodore Roosevelt (1858-1919) to raise and lead a volunteer force to fight in Europe, which posed an obvious challenge to the president’s authority, may have further convinced Wilson of the necessity of conscription. Secretary of War Newton D. Baker (1871-1937) was thus tasked with crafting a law that balanced the manpower requirements of the armed forces with widespread domestic concerns over civil liberties. The resulting bill was a radical departure from the Civil War draft. First, it eliminated provisions for substitutes, most exemptions, and enlistment bounties. Second, although the draft contained a legal prohibition against class and group exemptions, skilled workers deemed vital to the national economy were eligible for deferments. A provision was also made for ministers and divinity students, who were permitted to serve in non-combat roles if they belonged to a recognized religion with pacifism as one of its central tenets. Third, unlike in the Civil War, the administration of the draft was placed in civilian control. Draft boards were typically comprised of local officials drawn from pre-existing voting precincts. In theory, if not in practice, they were empowered to issue draft calls and grant deferments based on essential occupations.

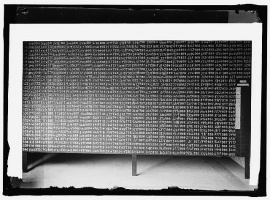

The federal government officially designated 5 June 1917 as “Registration Day.” On that date, all males between the ages of twenty-one and thirty were required to register for the “great national lottery,” drawing numbers that determined the order in which they were called for military service. Despite the legal prohibition against preferential treatment, local draft selections often reflected disparities along the lines of social class, race, and ethnicity. Draft boards disproportionately selected immigrants, poor rural farmers, and African-Americans for military service, groups widely deemed expendable by local community leaders, while largely exempting the upper classes.

Dissent↑

Resistance to the draft was significant, especially in rural areas. In addition to the 337,649 “draft deserters” who refused to report for military service, political opposition came from both parties, labor unions, women’s organizations, and interest groups on the political left. Progressive Democrats from Wilson’s party also questioned the government’s authority over individual freedoms, arguing that compulsory service would destroy “democracy at home while fighting for it abroad.” Opponents of the draft challenged the new law in federal court, arguing that it directly violated the Thirteenth Amendment’s prohibition against slavery and involuntary servitude. However, the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the draft act in the Selective Service Draft Law Cases on 7 January 1918. The unanimous decision reaffirmed that the Constitution empowered Congress to declare war and to raise and supply armies.

The original law was amended by Secretary of War Baker in August 1918. It broadened the age range to include all men between eighteen and forty-five and included a provision that allowed conscientious objectors to opt for alternate, non-combat military service. By the end of World War I, some 24 million men had been registered; of these 2.8 million were actually drafted into the armed forces. Despite the inequities of local draft selections and persisting controversies over universal conscription, the Selective Service Act was generally well received by the American public. It constituted a key component of the U.S. war effort, enabling the AEF to deploy some 1 million men to France by June 1918.

Michael Geheran, Clark University

Section Editor: Lon Strauss

Notes

- ↑ United States Provost Marshal General’s Bureau: Second Report of the Provost Marshal General to the Secretary of War on the Operations of the Selective Service System to December 20, 1918, Washington, D.C. 1919, p. 227.

Selected Bibliography

- Chambers, John Whiteclay: To raise an army. The draft comes to modern America, New York; London 1987: Free Press; Collier Macmillan.

- Coffman, Edward M.: The war to end all wars. The American military experience in World War I, Lexington 1998: University Press of Kentucky.

- Flynn, George Q.: Conscription and democracy. The draft in France, Great Britain, and the United States, Westport 2002: Greenwood Press.

- Keene, Jennifer D.: Doughboys, the Great War, and the remaking of America, Baltimore 2001: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Millett, Allan Reed / Maslowski, Peter: For the common defense. A military history of the United States of America, New York; London 1984: Free Press; Collier Macmillan.

- Stewart, Richard W. (ed.): American military history. The United States Army in a global era, 1917-2008, volume 2, Washington, D.C. 2010: Center of Military History, U.S. Army.

- United States Provost Marshal General’s Bureau: Second report of the Provost Marshal General to the Secretary of War on the operations of the Selective Service System to December 20, 1918, Washington, D.C. 1919: G.P.O..