Preliminaries↑

The origin of the Battle of Amiens – sometimes known as Amiens-Montdidier – was the German failure to capture Amiens during Operation Michael, the first of the German Kaiserschlacht offensives, which ended on 5 April 1918. The German Second Army under General Georg von der Marwitz (1856-1929) was left holding an overstretched salient to the east of the city. Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig (1861-1928), commanding the British army on the Western Front, began plans for a counterattack by his Fourth Army under General Sir Henry Rawlinson (1864-1925) in May. The French and Americans meanwhile halted and drove back the last German offensive in the Second Battle of the Marne 15 July-6 August 1918. The overall Allied plan on the Western Front, announced by Marshal Ferdinand Foch (1851-1929) as Allied generalissimo, was for a general offensive (“bataille générale”) of repeated and relatively shallow attacks on different parts of the German line, allowing the Germans no time for recovery.[1] At this stage, Foch and most other senior Allied figures expected the war to last well into 1919.

The Battle of Amiens↑

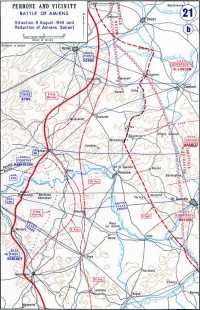

Under conditions of great secrecy, Rawlinson’s Fourth Army was almost doubled in strength to fourteen infantry divisions, made up of British III Corps, the Canadian Corps, the Australian Corps, plus an American division in reserve, together with most of the Tank Corps and the Cavalry Corps. The British had over 2,000 artillery pieces, together with 342 of the latest Mark V and Mark V* heavy tanks to break through the German defences, 120 supply tanks, and seventy-two of the new faster, lightly armoured Medium A “Whippet” tanks for exploitation. To the south of British Fourth Army, the French First Army under General Marie Eugène Debeney (1864-1943) was placed under Haig’s command to play a supporting role in the battle, with its XXXI Corps and IX Corps attacking alongside the Canadians. The attack was also supported by over 1,900 British and French aircraft. The German Second Army under Marwitz had ten weak divisions (plus four in reserve) on a front of about thirty kilometres facing the British and French, with at most 530 guns and 365 aircraft. Even this disparity does not fully convey Allied superiority in numbers, equipment, and morale over the Germans by this stage of the war.

The British attack began in the fog at 4:20 a.m. on Thursday, 8 August 1918, led by a creeping (or rolling) artillery barrage with no preliminary bombardment, achieving complete surprise. Lacking strong tank support, the French attacked at 5:05 a.m. after a short bombardment. The Allied attack broke through to capture the German first defensive lines by 7:30 a.m. In the centre Whippet tanks, armoured cars and cavalry then advanced at high speed to seize critical points on what was designated the Amiens Outer Defence Line, with more infantry divisions following up to join them. By mid-afternoon, the Canadian Corps and Australian Corps in the centre had advanced almost twelve kilometres on a front of twenty-two kilometres. In other sectors the offensive did not fully succeed. A surprise small-scale German attack on 6 August had disrupted British III Corps plans, and its attack was stopped short of the difficult Chilpilly Spur; the French First Army also captured its first objectives but then made only limited progress. The advance also suffered from the new problem of co-ordinating a mechanised breakthrough; co-operation between the tanks and cavalry failed, and the British Royal Air Force (RAF) focussed on attacking bridges in the German rear rather than tactically supporting the attack. The British continued their attack the next day with the Canadian Corps gaining another five kilometres. This brought British Fourth Army’s advance onto the wasteland of the old 1916 Somme battlefield, while eight German divisions were arriving to reinforce the defence. The French First Army captured Montdidier on 10 August. The fighting continued until 12 August with little further Allied gains, by which time losses and mechanical failures had reduced the British tank strength to six working tanks. With the Germans holding a new line in front of Noyon and Peronne, Field Marshal Haig closed the battle down and began preparing for another attack further north.

Aftermath↑

Famously, General Erich Ludendorff (1865-1937) in his memoirs described 8 August 1918 as “The black day of the German Army (Der schwarze Tag des deutschen Heeres) in the history of this war”.[2] Chiefly this was because of the impact of the Allied breakthrough on German morale, with the recognition that the last German offensives a month earlier, widely known as the Friedensturm, had failed to defeat the Allies. The German High Command accepted shortly after the Battle of Amiens that it had lost the war on the Western Front, something that was not apparent to most opposing Allied commanders until early October. Disputed casualty figures for both sides suggest 20,000 British and 24,000 French casualties for the battle, about 30,000 German surrenders, and estimates of total German losses as high as 75,000.[3] In retrospect, Amiens became for the British the decisive battle that began the “Hundred Days” campaign of successful attacks leading to victory on the Western Front. In terms of technology and the art of war, Amiens made a very strong contrast with the methods with which the Battle of the Frontiers exactly four years earlier had been fought by all sides. The contrast between the Fourth Army’s performance under Rawlinson at Amiens with the performance of the same commander and army at the Battle of the Somme in 1916 also showed the considerable improvements made in tactics, technology, staffwork, and leadership at all levels by the British army since 1916, and the extent of its superiority over the German army by 1918.

Stephen Badsey, University of Wolverhampton

Section Editor: Mark Jones

Notes

Selected Bibliography

- Harris, J. P. / Barr, Niall: Amiens to the Armistice. The BEF in the Hundred Days' campaign, 8 August-11 November 1918, London; Washington, D.C. 1998: Brassey's.

- Hart, Peter: 1918. A very British victory, London 2008: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

- Lloyd, Nick: Hundred Days. The end of the Great War, London 2013: Penguin Books.

- Ludendorff, Erich: Ludendorff's own story, August 1914-November 1918 the Great War from the siege of Liege to the signing of the armistice as viewed from the Grand headquarters of the German Army, volume 2, New York; London 1920: Harper & Bros..

- Messenger, Charles: The day we won the war. Turning point at Amiens, 8 August 1918, London 2008: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

- Schreiber, Shane B.: Shock army of the British Empire. The Canadian Corps in the last 100 days of the Great War, Westport 1997: Praeger.

- Simkins, Peter: From the Somme to victory. The British army's experience on the Western Front 1916-1918, London 2014: Casemate.

- Stevenson, David: With our backs to the wall. Victory and defeat in 1918, Cambridge 2011: Harvard University Press.