Memories of the First World War: Differences and Similarities↑

As Maurice Halbwachs (1877-1945) and the scholars who have expanded on his work stress, memory can be repeatedly re-constructed, specifically in respect of those who are reviewing the history. Even when a memory is fundamentally different from the event itself, it is not "wrong". Rather, the respective version reflects what is still important for the remembering subject - what lessons they want to, or should, draw. Films, games, novels, museums, or the visible traces of the former theaters of war have had an influence on what remained relevant from the First World War for the given present. The media have transmitted emotions and ideas, both for the eyewitnesses and those who did not experience the event itself. They have conveyed images, sounds, and objects. Finally, they have provided - more or less explicitly - interpretative points of view.

While the Second World War is undoubtedly perceived as a struggle for a just cause in which there were clear victors, its predecessor is considered a prime example of the senselessness of millions of casualties. Primary sites of remembrance include the costly major battlefields in Flanders, along the Somme, near Verdun, in the Alps, and on the Turkish peninsula of Gallipoli. Museums, exhibits, comics, movies, and novels all direct attention to the destruction of the landscape, the people, their countries, and their hopes and dreams. No one is able to make sense of the slaughter, but there are heroes. The movies from the 1920s can be already described as media of a unifying memory. The lavish productions were intended for an international market, for this was the only way that the production costs might be absorbed. Images of the enemy receded into the background, along with narrow national interpretations of the conflict. In the film Joyeux Noël (2005), the French director Christian Carion conveys the message most clearly that the roots of European unity and reconciliation were laid on the battlefields of 1914, namely, where enemy soldiers celebrated Christmas together.

An important difference in the memory of the First World War is reflected in the admiration expressed for the combatants: in France and Britain, notwithstanding the perception that the war was a tragedy, the fallen and the veterans are revered. The significance ascribed to 11 November as a public holiday in France (Mort pour la France), Great Britain (Remembrance Day) and Belgium (Armistice 1918) shows the extent to which the commemoration of the war unites these societies. In Australia and New Zealand, Anzac Day on 25 April is a sort of national holiday. By contrast, in Germany, Russia, Austria, and Japan, an official day of remembrance was never introduced. In France and Belgium, the idea that the fatherland was rescued and liberated from the occupiers is even more central to the memory of the war than in the UK and has wide acceptance. The Commonwealth countries remember the bloody battles with a comparable mixture of admiration and sorrow for the sacrifices that were made. While the war should not be repeated, the pride in the willing sacrifice of tens of thousands of young men who threw themselves into senseless battles is nevertheless palpable in Australia, Canada, and New Zealand. This is due, not least, to the fact that their sacrifice paved the way for independence from the British Empire.

While in France and the UK, for instance, the great demand to commemorate the First World War has not diminished for almost 100 years, the public interest in Germany is experiencing a newly-awakened interest on the occasion of the centenary. Truly transnational projects - such as common textbooks or comics - are still quite rare.[1]

This article is divided into three parts. After a brief discussion of the differences and similarities between the cultures of memory, the second section will elaborate on the popular media that have been particularly influential with regard to commemoration over the last 100 years. The third section provides a chronological overview of the phases of remembrance and concludes with a brief consideration of the centenary.

Media of Popular Memory↑

Long before the last veterans died - Lazare Ponticelli (1897-2008) in France; Erich Kästner (1900-2008) in Germany; Harry Patch (1898-2009) in the UK; Claude Stanley Choules (1901-2011) in Australia, and Frank Buckles (1901-2011) in the USA - the memory of the conflict was not only in the hands of its eyewitnesses. Novels, movies, museums, games, music, painting, comics, and the battlefields themselves were, and remain, popular media that tell about the war, shape the memory of it, and, above all, reach a large audience. "Popular memory" includes all media that evoke the First World War and are outside of the realm of research and knowledge production. Of course, these are ideal-typical delimitations: popular memory is conveyed and shaped by media that reach a wide audience. These media do not in the first instance want to educate; they primarily aim to entertain. At the same time, they have occasionally served the purposes of propaganda, as well as expanded on research findings.

Graphic Novels↑

All of the popular media, which are addressed in this article, were already in existence during the war. Of course, they were considerably different from today. Film, for instance, was still silent (until 1930). A sense of drama was created in the cinema by musicians or narrators. The forerunners of today's graphic novels were illustrated magazines and broadsheets, which sought to explain the complex power relationships and alliances to their (not only younger) readers. Often, they spread savage images of the enemy, showing them as feral and malicious animals or as particularly ugly and brutal people.[2] The victims - for example, in the occupied Belgian or French territories - were frequently depicted as beautiful women or tender children, who had been tortured and raped. Some motifs, narrative structures, or justifications were perpetuated after the end of hostilities. The most important was undoubtedly the pervasive topos of defensive war.

Today, most media have moved away from stereotyped patterns of interpretation. Graphic novels have been emancipated. The works of Jacques Tardi (Putain de Guerre!; C`était la Guerre des Tranchées), Kris and Maël (Notre Mère la Guerre), Jean-Denis Pendanx (Svoboda!), Jean-Pierre Gibrat (Mattéo), Joe Sacco (The Great War) or David Vandermeulen (Fritz Haber) use the medium for narratives about the war that are based on historical facts. Their perspective is that of the common soldiers and the often forgotten unsung heroes: the black soldiers, the aborigines, and the deserters.[3] The comic authors interweave war reports with their own detached reflections. They emphasize the obviously constructed character of the individual images (panels) and ostensibly authentic photographs, which, in the age of digital manipulation, are not reliable representations of reality, if they ever were. They consciously focus on the story’s design, without however abandoning the aim to tell it in a way that is historically accurate. Graphic novels encourage the reader to think, because the gaps need to be filled in between the individual images. The reader herself develops the story between the panels at her own pace.

Jacques Tardi attaches great importance to the accuracy of the objects he draws. He researched them and sources (mainly from the collection of Jean-Pierre Verney) so intensively that his stories have an unmistakeable documentary quality. This documentary work in his comics culminates in unmistakable pacifist propaganda. Tardi fights against the war.[4] Kris and Maël, on the other hand, offer no slogans or answers; they pose the question about why the soldiers fought. Drawing on the research of Nicolas Offenstadt and André Loez, they tell of soldiers who were not simply patriots or pacifists.[5] And they deal with the hotly disputed topic of the poilus, who were court-martialed and shot as a deterrence. This subject had long been a taboo in the public memory, but also in the research.[6]

Games↑

The catalogs of toy retailers were even swollen in the years from 1914-1918. Many games were adapted to the war - not only the clothes of the dolls, but also popular board games, like the "Game of the Goose" in France, were updated with illustrations of victorious French and pillaging German soldiers.[7] Children and adolescents came to terms with their terror and fear through play. Building blocks could be assembled into the ruins of the houses of Verdun. The toys justified the war as a fair defense, demonized the enemies, and mobilized children and adults. When weariness over the war became evident in France in 1916, the conflict took a backseat, without disappearing completely. After 1918, the victory was the most important thing; children no longer played war.

In the meantime, the games market has become international. Computer and video games have been especially successful. They have high development costs, which only pay off if there is access to a global market. Between 1981 and 2009, around 1,600 games with a historical background appeared on the German market. The First World War, however, was a minor phenomenon: with less than 5 percent, it was last among the gaming-grade historical events.[8] The rigid frontlines in the West are obviously not appealing for strategy and action games. The First World War also stands in the shadow of the Second World War when it comes to games.

Novels↑

The first novels were written by eyewitnesses such as the French physician and writer Georges Duhamel (1884-1966), and Roland Dorgelès (1885-1973). Both used fiction to bring out the essence of the war. Dorgelès, whose novel Les Croix de Bois appeared in 1919, remarked that instead of telling of countless fates and events, he incorporated into an imaginary plot the slightly altered impressions of his own experience on the front. He also re-created the reality in the novel because he dreaded describing the actual fates of his fallen comrades at the front.[9] The earliest novels, such as Le Feu by Henri Barbusse (1873-1935), were published during the war, and reported on the war experiences of the author, often in dramatic form. They were printed, read, honored, and translated during the war, or censored, as in the case of Fritz von Unruh’s (1885-1970) Opfergang (Sacrifice). Written on behalf of the Supreme Command from the experiences of the Battle of Verdun, the work was first published in 1919. The poems of Wilfred Owen (1893-1918), Siegfried Sassoon (1886-1967), Rupert Brooke (1887-1915) and Robert Graves (1895-1985) brought a different reality of the war to readers: mutilated bodies, nightmares, hallucinations, criticism of warfare, fear of death, and the desire for peace. The soldiers wrote for themselves, for their comrades, and for the fallen. Their works can be read as literary monuments to the dead.[10] To this day, the works of the war’s veterans convey fascination and horror. Standing side by side are the cool, detached descriptions of Ernst Jünger (1895-1998), best known for the repeatedly self-revised work Storm of Steel; the sharp analyses of belligerent society of Arnold Zweig (1887-1968); or novels with pacifist undertones, such as Krieg (War) by Ludwig Renn (1889-1979), who joined the German Communist Party in 1928. Amidst the barrage of war novels, the drama Die letzten Tage der Menschheit (The Last Days of Mankind) by the Austrian satirist Karl Kraus (1874-1936) stands out. Between 1915 and 1922, Kraus created a collage of original quotations. The absurdity of war was clearly expressed in his tragedy, which he intended to be unperformable, as well as in his still-impressive analysis of the role of the media in war.

Ten years after the First World War, in January 1929, Erich Maria Remarque’s (1898-1970) Im Westen nichts Neues (All Quiet on the Western Front) appeared. The German writer was also a war veteran. His bestseller centers on how the young men’s idealism is exploited. Remarque's novel dramatically conveys their sense of disorientation. Remarque as well as the American author Ernest Hemingway (1899-1961), whose novel A Farewell to Arms was published in 1929, describe the "lost generation." These books soberly describe a generation that was destroyed by the war, even for those who survived the grenades. In 1933, the memoir of Vera Brittain (1893-1970) was published under the title Testament of Youth. The young Briton had lost her fiancé, her brother, and two friends in the Great War. The experience of loss informed her pacifist attitude.

Among the wealth of poems, novels, and memoirs, Die Abenteuer des braven Soldaten Schwejk (The Good Soldier Švejk) is especially noteworthy. With Svejk, the Czech author Jaroslav Hašek (1883-1923) created a character who cunningly evades having to do military service in the Austro-Hungarian army. The Eastern European memory of the war, above all, has been shaped by this three-volume work. In 1971, Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s (1918-2008) August 14 was published by a French publisher. Drawing on German and Russian sources and modeled after Leo Tolstoy's (1828-1910) War and Peace, Solzhenitsyn knowledgeably describes the Battle of Tannenberg in late summer of 1914. The novel is characterized by a critical view of the Russian military and political leadership.[11] One of the few Eastern European voices was Boris Pasternak’s (1890-1960) novel Doctor Zhivago. This work was also not published by a Russian publisher, but rather appeared in Italy in 1957. The plot covers the years 1903 to 1929/1943. A trend emerges here that became increasingly important for popular memory up to the present: the First World War is specifically embedded in the larger context of violence and the civil wars of the 20th century. Seldom read is Wolfgang Koeppen’s (1906-1996) novel Die Mauer schwankt (The Wall is Swaying) from 1935. Based on his personal experiences, he describes the time of the Russian occupation in Masuria in late summer 1914 and the mass destruction.[12] Siegfried Lenz (1926-2014) also describes the Russians’ occupation of Masuria in 1914 in his novel Heimatmuseum (The Heritage, 1978), which relies on extensive sources. This chapter, however, reads first and foremost like an intense reflection on home.[13]

The bestsellers of the past twenty-five years have continued in this vein. In Les Champs d'Honneur (1990), Jean Rouaud remembers his uncle Joseph, who died from poison gas at the Battle of Ypres in 1916. Rouaud also ties together the two world wars in a context of violence. His novel is simultaneously a meditation on forgetting. Through his narrative, he preserves the memory of one of the countless dead of the First World War. This connects him to the early "écrivains-combattants."

Sébastien Japrisot’s Un long dimanche de fiançailles (1991) and Marc Dugain’s La Chambre des Officiers (1998) have been made into successful films. Their work revolves around the war’s manifold injuries, wounds, and mutilations. Pat Barker's Regeneration Trilogy (1991-1995) is similar in this respect: the novel gives the reader a vivid understanding of the mental and physical wounds caused by the First World War. Graves, Owen, and Sassoon appear as protagonists. The British author developed the dialogues based on the autobiography of Robert Graves: Good-bye to All That (1929). Pat Barker asks a lot of her readers, because the violence in the trilogy is not limited to the combatants. With a nearly unbearable brutality, doctors try to "cure" the mentally ill soldiers. Much like in the film by G.W. Pabst (1885-1967), Westfront 1918 – vier von der Infanterie (Western Front 1918; Germany, 1930), violence in her novels is inflicted by all members of society, including women.

Feature Films↑

Films comprised an important propaganda tool during the war. Like many novels, they, too, were a hybrid of documentary and fiction. By the mid-1920s at the latest, images of the enemy were no longer relevant in feature films. This was partly due to the fact that the elaborately produced movies needed an international market to cover their costs. By the time of the classic Im Westen nichts Neues (USA, 1930), directed by Lewis Milestone (1895-1980), the filmic treatment of the war had been inserted into an interpretive framework that continues to this day to influence the popular understanding of the First World War. Milestone’s film tells the stories of young, idealistic men who are seduced by the war. In Renoir's masterpiece La Grande Illusion (France, 1937), the focus is on one of the doomed social classes; American director Stanley Kubrick (1928-1999) accused the military leadership of being a caste which moves soldiers like pieces on a chessboard, sending them to their deaths (Paths of Glory, USA, 1957). In the films that are still esteemed today, the enemy plays no role as an opponent who offers a justification for the bloodshed. Not a single German soldier is shown in Paths of Glory. The real enemies of the ordinary soldiers are the generals who lead them. They have their own soldiers court-martialled and shot as a deterrence. G.W. Pabst’s film Westfront 1918 – vier von der Infanterie (Germany, 1930) offers a similar interpretation of the novel by Ernst Johannsen, upon which it is based: violence determines the coexistence of man and woman, and the women do not even show sympathy with mourners in line at a grocery store. In the final sequence in the hospital, a French poilu grabs the hand of a dead German soldier: "Not enemies," he whispers. But the artillery fire continues and is even heard after the story’s conclusion. The last shot asks: "The End?"

Several feature films such as War Horse (USA/GB 2011, director: Steven Spielberg); Un long dimanche de fiançailles (France/USA 2004, director: Jean-Pierre Jeunet); or Passchendaele (Canada 2008, director: Paul Gross) use images and footage from the war years to create the most realistic depiction possible. Sometimes photos are transferred 1:1 into the story, whereby a black-and-white photo dissolves into a moving color sequence.

There are no significant films that try to make sense of a particular battle or victory. The focus is on the victims of the soldiers, the suffering - even of animals (War Horse) - and the destruction of nature. Some of the feature films that are still considered masterpieces were made in the interwar period. Directors like the American William Wellman (1896-1975) (Wings 1927) or Jean Renoir (1894-1979) were veterans and brought their experiences to bear. In the process, they ensured a high degree of authenticity. Jean Gabin (1904-1976) in La Grande Illusion thus wore the uniform of director Jean Renoir. Most of the films that are viewed as classics today and to a large extent shape our impression of the First World War were produced in the United States - a country that did not enter the war until 1917 and whose territory remained intact. The Second World War even superseded its predecessor in this genre of film, which is still evidenced today by the much higher number of related movies. In 1957, with Paths of Glory, Stanley Kubrick offers a depiction of battle in which the planning breaks down due to the circumstances of a complex reality. Paths of Glory was not shown in French cinemas until 1975. The concern that the film could undermine the strength of the military was shared by both French and German censors. Popular media were certainly capable of triggering controversy. The memory of the war never simply looked back, but rather referred the past to the present. In 1930, the Nazis undoubtedly sparked the most heated public debate about the “correct” form of remembrance in response to the American film All Quiet on the Western Front. After a tremendous gain in votes in the elections of September 1930, the anti-republican Nazis made clear which aspects of the memory of the world war in their view should no longer be permitted. The memory of the right, which radically excluded any alternative interpretations after 1933, instrumentalized the past to legitimize future war. Thus, the scene elicited criticism in which German soldiers, far from the frontline, devoured a double ration of food after fierce fighting. Director and producer were accused of keeping up images of war propaganda. As a symbol of barbarians, German soldiers were often depicted with strings of sausages around their necks and sauerkraut in their hands.

The long list of films (only a few of which are significant)[14] shows that the Western Front is by far the most important site of remembrance. There are, accordingly, few films about the events in Russia (The End of St. Petersburg, 1927, director: Vsevolod Illarionovič Pudovkin); the war in the Alps (Mountains in Flames, Germany 1931, directors: Luis Trenker and Karl Hartl); or other theaters of war (Gallipoli, Australia 1981, director: Peter Weir); (Çanakkale 1915, Turkey 2012, director: Yesim Sezgin); and (Lawrence of Arabia, Great Britain 1962, director: David Lean). The Western Front also predominates in literary and artistic treatments. There are many reasons for this. First, recent military history focused on the Western Front for a long period, as all the elements of the new, almost total war, emerged there. In the years of the Cold War, the "East" was a blind spot for Western research; the Soviet Union, for its part, merely viewed the Empire’s war as the cause of the Revolution of 1917. All this changed dramatically with the onset research and commemorative boom of the 1990s.

Art↑

Some artists thought the war was inevitable, while others, like Franz Marc (1880-1916), considered it a purifying force. "The war is fought for purification, and the sick blood is spilled."[15] At first, only a few critical voices were heard. Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944) quarreled with his friend Marc. Looking ahead, he warned: "The price of this kind of cleansing is horrific.”[16] The glorification of war did not always spring from patriotic feelings, but, as with the Futurists, was sometimes connected with the hope of overcoming the bourgeois world. In their manifesto from 1909, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti (1876-1944) rhapsodized: "The only beauty that remains is in battle."[17] In 1915, the Italian added that war was the world’s only hygiene.

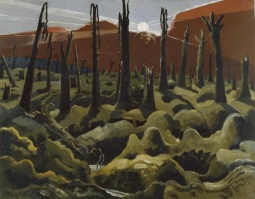

Some artists put themselves in the service of propaganda. Fritz Erler (1868-1940), for instance, designed the poster for the sixth war loan campaign of 1917, which brought in more than 13 million marks. Among the official war painters there were well-known artists such as Max Slevogt (1868-1932) and Paul Nash (1889-1946). Artists like Theodor Rocholl (1854-1933) who are less well known today, remained committed to a euphemistic style of military and battle painting, while others emancipated themselves from their customers and created works that continue to provide the viewer with an impressive picture of battle. Nash's images of the destroyed Flemish landscape do not convey any of the values for which the soldiers fought; he captures, instead, the destructive power of war. The title We Are Making a New World was an unequivocal rejection of all the ideals that drew people into the war.

Other artists who fought as soldiers captured their impressions in sketches and, during rest periods and after the war, created works that are still considered emblematic. Among them are Max Beckmann (1884-1950), who served as a medical orderly on the Eastern Front and in Flanders, and Otto Dix (1891-1969). Dix's etchings expressed the destruction of the landscape no less than that of the bodies and souls. The artist fought at the Western and Eastern fronts for four years. He considered himself a witness who needed to preserve his impressions. He wanted to take part in the war, which he sensed to be an extreme life experience. Dix did not offer explicit commentary, unlike the volunteer soldier George Grosz (1893-1959) with his drawing from 1928, "Maul halten und weiter dienen" ("Shut your mouth and continue to serve"). At the same time, Dix’s paintings in the early 1920s of war cripples who are excluded from society (and peed on by dogs) can be seen as such an expression.

There was a broad range of forms of representation: The naif, colorful, patriotic, and propagandistic images of Raoul Dufy (1877-1953), reminiscent of the broadsheets from Epinal, accompany the cubistic paintings of Christopher R.W. Nevinson (1889-1946), one of the official British painters. Their images were widely distributed. Reprinted in picture books, reproduced as poster or postcards, or shown in war exhibits, many of the works already reached a broad public during the war. Mainly Cubism, but also Futurism and Expressionism, proved best suited for reproducing the disturbing experiences of the soldier-artists. Nevinson’s La Mitrailleuse or Percy Wyndham Lewis (1882-1957) A Battery Shelled appear as worlds that have been poorly cobbled together from fragments. These art forms were also appropriate for much more immediate use in the war: In camouflage units, painters like Louis-Victor Guirand de Scevola (1871-1950) and André Mare (1885-1932) created great tarpaulins, under which guns could be hidden from the eyes of enemy reconnaissance.

In 1915, Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968) fled the war to the United States and laid the foundation in New York for his concept art. In Russia, Kazimir Malevich (1878-1935) discovered complete abstraction. His Black Square (1915) was one of the most radical breakthroughs in art during the war years. Beginning in 1916, the artist gained notoriety with provocative actions as part of the Dada movement in Switzerland, where he took refuge. They put everything into question, including the war and bourgeois art. They even banished language itself from their onomatopoeic poems.

The messages were as diverse as the works themselves: Malevich (and many others) denounced the atrocities committed by the Germans or Austrians. In Russia, artists designed posters. They made an appeal to support the frontline soldiers and to make donations, although they abstained from any criticism of the government. Broadsheets enjoyed great popularity. They were able to portray the exploits of the Russian army, or they presented colorful graphics designed by artists such as Malevich and Mayakovsky, which, moreover, contained sardonic rhymes: "We will blot the mouth / of Wilhelm of Hohenzollern. / The brush is our lance. / We smear it with paint, and no one will get it clean again!"[18]

John Singer Sargent (1856-1925) drew the viewer’s attention away from the supposedly great military events to the lives of the combatants themselves. For example, he depicted a group of British soldiers who, having been blinded by a gas attack, rested their hands on each other’s shoulders for support. Representations like these did not go unchallenged: In his Paths of Glory from 1917, for example, Nevinson had shown two fallen British soldiers, apparently carelessly left behind in the mud. The censors tried to prevent the work from being shown, but he exhibited it again in 1918 - covered over by a large piece of paper with the words "censored" - and sold it.

The shock that undoubtedly all artists had experienced, and the discrepancy between the ideas of war before 1914 and the experience on the battlefields and at home, are also reflected in two paintings from Lovis Corinth (1858-1925). In 1914/15, he created a self-portrait showing him in shining armor. In the 1918 painting Rüstungsteile im Atelier (Armor in the studio), the suit of armor that he wears in the picture from 1914/15 now lies empty in pieces on the floor of his studio. Like no other medium of popular memory, art continues to this day to feed on contemporary creativity. Whereas in the case of novels, comics, or feature films, outstanding works were produced by later generations, all the works of art that bring us closer to the entire panorama of the war and its diverse interpretations were made by war veterans or eyewitnesses.

Popular Memory 1918-2014↑

Sites of Memory near the Former Battlefields (1919-1940)↑

After the cease-fire agreements were signed and the troops were withdrawn, the clean-up efforts began. Metal and unexploded ordnances were collected, as well as bones. In France, around 350,000 houses were destroyed, along with 11,000 public buildings and 62,000 kilometers of railway lines. An area of about 116,000 hectares was declared a red zone, i.e. due to the contamination with explosives and toxic substances the area was determined uninhabitable. The reconstruction went faster than expected: by 1922, three-quarters of the agricultural area was already restored.[19] The town of Ypres, which was almost completely leveled, was rebuilt as an idealized version of Flemish culture, tradition, and architecture.[20] Fascinated by the medieval appearance of the city, most visitors today are unaware that hardly a building is more than eighty years old. Often, traces of the war that remained were also due to the fact that the trenches were part of a cemetery or a memorial (Vimy, Beaumont-Hamel) or private property which had not been re-cultivated (like a mine crater near the village of La Boiselle of the Somme that was acquired in 1978 by the Briton Richard Dunning; it is used to this day for a commemorative ceremony on 1 July, centering on the reconciliation of later generations).[21]

In 1920, Marshal Philippe Pétain (1856-1951), the "Savior of Verdun," placed the cornerstone for an ossuary, where the human remains were to be collected that had been recovered in fifty-two sections of the battlefield at Verdun. The ossuary was dedicated at Douaumont in 1932. Through small windows just above the ground, the visitor is still able to see mountains of bones. The memorial contains 130,000 bodies, and has served as a substitute grave and place of worship for loved ones since its opening. The effort was remarkable: In the mid-1920s, in the section Chemin des Dames, between eighty and 100 corpses were recovered every month. From the UK, 4,000 gravestones were transported monthly to France, and 100 kilometers of hedges were planted around British cemeteries. The area around Verdun was developed into a memorial complex. The places that were completely destroyed in the war – for example Fleury - were not rebuilt. However, in order to make sites recognizable that were no longer visible, monuments were erected that pointed them out to the visitor. By 1923, over 200 memorials of war had already been enshrined by law in France. Trenches, a huge mine crater, a contested hill, a shelter, the forts of Verdun - places that marked the outcome of a campaign or the breakpoint of the enemy's attack - everything was to remain as it been conquered in battle, fought over, and destroyed. According to the Bill’s wording, the law was intended to help children remember, as well as to understand and judge other nations.[22] With government assistance and by force of law, monuments were erected in more than 30,000 locations in France and in the colonies by the mid-1920s. Fearing a lack of quality (and empty coffers), the government promoted a standardized configuration in France with a catalog of monument patterns. The reason that 11 November was already declared a holiday in 1922 was due to an initiative of the Ancien Combattants, against the will of the government. Although the holiday commemorates the country’s victory, its focus rapidly changed from being a victory celebration to a remembrance of the fallen.[23]

In 1932, the Thiepval Memorial on the Somme was dedicated to more than 72,000 British and South African soldiers who had no known graves. The terrain is dominated by a topsy-turvy, forty-six-meter-high triumphal arc designed by British architect Edwin Lutyens (1869-1944). Reached by stairs, at the center of the monument is the Stone of Remembrance, which can be found at all British war cemeteries of the First World War that accommodate more than 1,000 graves. The stone, which recalls both an altar and a sarcophagus, bears the inscription: "Their name liveth for evermore." The engraved name lists are updated to this day to correct typographical errors or to delete a name because a body was found and identified. The Franco-British cemetery adjoining the monument is dedicated to the memory of the military alliance.[24]

In the interwar period, battlefield tours were perhaps the most important form of popular remembrance. In most cases, relatives visited graves or large memorials, which served as substitute graves: Thiepval, the Douaumont Ossuary, Notre-Dame-de-Lorette or the Menin Gate in Ypres.

In the homeland, monuments were erected in nearly every location. In Germany and Great Britain, private initiatives and collections were often responsible; in France, by contrast, most were built with government support. In Great Britain, the war memorial was marked from the outset by a strong desire for peace. The poppy became a symbol of mourning over the “lost generation.” The poppy pin is still distributed today by the British Legion.

Australia, Canada, and New Zealand also erected large memorials at the former Western Front and on the Turkish peninsula of Gallipoli, which were visited in the interwar period by tens of thousands. The Battle of Vimy Ridge of 1917 over a part of the frontline played an important role for Canadian soldiers, who achieved a breakthrough there. A large memorial complex was created here between 1925 and 1936. [25] The area is dominated to this day by the monument of a grieving woman, representing Canada, which is visible for miles around. Both the conserved trenches and the forests now pockmarked with craters present the last traces of mechanized warfare to today's visitors. The names of 11,285 missing Canadian soldiers are engraved on the base of the monument.

One of the largest pilgrimages took place to mark the dedication in 1936. Around 8,000 Canadians alone traveled from their homes to the site, with some even receiving paid leave. It is estimated that approximately 100,000 people, including tens of thousands of French, participated in the inauguration ceremonies. The speech of Edward VIII, King of Great Britain (1894-1972) was simultaneously broadcast over the radio, allowing listeners back home to participate. Illustrated books flew off the shelves. In the reporting on the pilgrimage, the Royal British Legion stressed the unity of the Empire and spoke of the rekindled memories of a shared sacrifice.[26] The reporting further emphasized that the successful battle was evidence of a maturing Canada and justified cutting the umbilical cord from the mother country. The pilgrimage combined private with public memories. For the travelers, a number of different feelings merged: pride, sadness over the loss, camaraderie, and the belief that Canada deserved to be treated as an equal partner.[27]

Gallipoli remains a destination for Australian and New Zealand travelers. When landing on the Turkish peninsula in April 1915, 8,140 Australians and 2,700 New Zealand soldiers met their deaths: and more than 20,000 were wounded. One out of every seven Australian soldiers died. Already during the war, the victims were exploited for further recruitment campaigns (Australia was a volunteer army to the end) and the day on which this sacrifice is remembered was established as a holiday (Anzac Day, 25 April). On the Australian monuments, not only are the fallen remembered, but the names of those who volunteered are also inscribed.[28] Similar to the Canadian culture of remembrance, the sacrifices made and the service rendered provided the basis for standing on equal footing with Great Britain in the future. Although few family members were able to take such a trip in the late 1920s, Gallipoli continues to be a destination for tourists, and not only because travel has become faster and cheaper. Young backpackers from Australia visit cemeteries and former battlefields, because they are part of a route to diverse landmarks. Interviews suggest, however, that these visitors associate different emotions with the site of remembrance - they feel pride in their country, but also develop a sense of the transience of empires.[29] Thus, it seems that the experience and perceptions relating to travel to places of remembrance of the First World War change and are dependent on the time period and the individual.

For many Turks, Gallipoli evokes an entirely different memory. The battle is remembered - even in Turkish literature - as the success of the brave Turkish army against a presumably superior opponent, specifically through the belief in one’s own nation.[30] As the later President Mustafa Kemal Atatürk (1881-1938) was a general at that time, the prevailing view, which also serves as a national founding myth, is that Turkey began in Gallipoli.

The former front was also the place for the reconciliation of enemies. The French parliamentarian Marc Sangnier (1873-1950), one of the fathers of the international youth hostel system, organized a meeting in 1926 of more than 5,000 participants, who discussed young people and peace. Part of the program involved a trip to the battlefields.[31] He continued to organize such "pacifist pilgrimages" in the following years. Erich Maria Remarque not only described in the continuation of All Quiet on the Western Front (The Way Back) a momentous return to the former war zone. Even the protagonist in his short story "Karl Broeger in Fleury" ("Where Karl had Fought") recognizes during a visit to Verdun that the only way which points to the future is to accept the outcome of the war. The short story "Josef’s Wife" allows for a similar interpretation: On a journey to the former frontline, a veteran regains his memory after reliving his experience of having been buried alive. He then heads into the future cured.

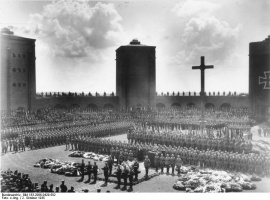

In 1936, on the twentieth anniversary of the Battle of Verdun, German and French veterans gathered at the Douaumont Ossuary. The impressive ceremony concluded with a peace oath. From today's perspective, the oath seems hypocritical in view of the swastika flags and the Nazi salute. Many of the cemeteries established over the course of the 1920s by the German War Graves Commission in France and Belgium were publicly exploited in Germany to prepare for a future war that would supposedly nullify the German defeat in 1918. Certainly, the best example of this is Langemarck cemetery: at the site, bunkers from the war years were restored and were able to visually express the view that the German army went unvanquished in the field of battle. Narrow crosses that marked no actual grave could be interpreted as a tribute to those yet to be buried. The tribute that stood over the entrance was explicit: "Germany must live, even if we have to die."[32]

Museums were another important site of popular memory. Many plans for regional and local war museums that had been developed during the years 1914-1918 were quietly dropped, however, both in the victorious and in the losing states. In Great Britain, only the Imperial War Museum was opened. The Leblancs, who had already begun an extensive collection during the war that became the basis for the Bibliothèque de Documentation International Contemporaine, organized several exhibitions in the immediate postwar period. Nonetheless, the memory of the destruction, the occupation, the dead, and the maimed was still all-too present for museums and exhibitions to be necessary, especially in France. In Germany, the defeat shattered all museum plans. It was not until ten years after the war that exhibitions showed some success. In May 1933, the World War Library opened in Stuttgart, a private war museum equipped with numerous objects from its own collection. The museum justified the future war that would undo the injustice of the Versailles Treaty.[33] Both the Leblanc collection and the inventory of the Stuttgart World War Library were badly damaged in the Second World War.

In 1923, an unprecedented museum - even by international standards - opened in Berlin: Ernst Friedrich’s (1894-1967) "Anti-War Museum." It refused to idealize the conflict in any way and showed, among other things, the photographs of soldiers whose faces had been ripped apart by shrapnel. Friedrich belonged to a small group of pacifists who were politically influential in neither Germany nor Europe during the interwar period. His book War against War, in which he attempts to discredit justificatory war slogans in four different languages, remains worth reading today. Friedrich’s museum was closed in 1933 and a Sturmabteilung (SA) museum was put on its premises.

The commemoration of the First World War was provisionally concluded at the former battlefields in 1940. After the German victories over France, Belgium, and Luxembourg, Adolf Hitler (1889-1945) purposely staged the revision of 1918/19. He not only visited the German Langemarck military cemetery, but also Allied monuments (such as Vimy) and places where he had fought in the First World War. For the signing of the ceasefire agreement, Hitler had the railroad car sent from the museum in Compiègne. This well illustrates the extent to which the memory of the First World War was also exploited politically.

Remembering after the Second World War↑

After 1945, the memory of the First World War was overshadowed by the conflict that followed. Nevertheless, in France, focusing on the First World War made it possible to repress painful issues such as the collaboration with the Nazis. Verdun offered the possibility of internal and external reconciliation. Here, the conflicting memories of the Gaullists and the Pétainists could be bridged. In 1966 - for the fiftieth anniversary of the Battle of Verdun - 10,000 veterans went to Douaumont. Charles De Gaulle (1890-1970) declared in a remarkable speech that Europe's future depended on the reconciliation of neighboring France and Germany. The speech legitimized the friendship treaty that the countries had signed three years earlier and allied the former rivals in the fight against the new threat from the east. The handshake of François Mitterand (1916-1996) and Helmut Kohl in 1984 marked a further stage in the political culture of remembrance. It should not be forgotten, however, that Kohl’s invitation was intended to remedy the fact that the German Chancellor had not been invited to the D-Day celebrations the same year.

The 1960s mark in other ways a return of the public’s interest in the Great War. In France, for instance, there was the TV series "1914-1918 – La Grande Guerre," supervised by historian Marc Ferro. Ferro's research emphasized putting the simple soldier center stage. Starting in the 1960s, the number of surviving veterans declined rapidly: whereas in 1966, 10,000 former combatants took part in the celebrations in Verdun, there were only 200 in 1986.[34] At the same time, the need to recall their stories and their faces increased.

The memorial in Fleury (near Verdun) was established in the late 1930s as part of an initiative by the veterans themselves. At first, the Second World War put their plans on hold. In 1959, former Verdun soldiers took up the idea once again, and the museum opened in 1967.[35] Built on the traces of the former war zone, it appears to have been the first museum to open its doors. The Fleury museum overwhelmed visitors with the large number of veterans’ personal mementos. Since many were already familiar with the site’s importance, there was only scarce - mostly technical - information on the exhibits. For younger visitors who traveled to Verdun from 1980s and 1990s, there was a lack of contextualization. On 21 February 2016 - the 100th anniversary of the beginning of the offensive - the museum was reopened after a complete redesign. The focus is placed on the experiences of German and French soldiers. The official dedication on 29 May 2016 was presided over by German Chancellor Angela Merkel and French President François Hollande. It included the unveiling of a plaque at Douaumont Ossuary stating that there lie the remains of more than 130,000 missing French and German soldiers. It marks a further step towards the cultivation of a shared memory, which does not exclude divergent points of view.

In Great Britain, too, the remembrance of the First World War changed in the mid-1960s. First, the peace movement brought a critical tenor to commemoration, and skepticism was reinforced by publications on the General Staff - like the controversial book from the politician Alan Clark (The Donkeys), which compared the military leaders to donkeys who led the lion-like fighting soldiers to their deaths. Public interest was further piqued by a twenty-six-part television series from the BBC that was aired on the fiftieth anniversary of the beginning of the war.[36] The Imperial War Museum had opened its extensive archive for the first time for such a production. Anthony Noble Frankland, the director of the museum between 1960 and 1982, knew what treasures it contained. Since then, the sale of image and film rights has been an important source of income for the British War Museum, underlining the importance of the museum for the popular memory.

No comparable vestiges of the war remain on the former Eastern Front. The massive Tannenberg Memorial - dedicated in 1927 and designated a memorial of the Third Reich in 1935, one year after the burial of the former Field Marshal and President Paul von Hindenburg (1847-1934) - was destroyed by the Red Army in 1945. Today, the monument is designated by an information board in Polish, English, and German.[37] On the peninsula of Gallipoli, where heavy losses were incurred by the Dardanelles Campaign, more than eighty cemeteries and monuments attract visitors from the Commonwealth countries as well as Turkey.

Memory Boom in the 1980s↑

From the mid-1980s, interest grew steadily in the First World War, and the 1990s witnessed a veritable memory boom in all the countries involved in the conflict. For the countries of Eastern and Southeastern Europe, commemoration was a new phenomenon. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1989/91, the First World War emerged from the shadow of the Second World War and the Russian Revolution of 1917. But even in countries like Ireland, Australia, Canada, or New Zealand, which managed to gain independence from the United Kingdom due to their contributions in the Great War, there has been a growing interest in the First World War since the mid-1990s. The rapid rise in the number of scholarly publications attests to this boom as much as the dedication of new museums, for example the Museum of the Great War (Péronne) in 1992, the In Flanders Field Museum (Ypres) in 1998 (reopened in 2012 after renovation), the Musée de la Grande Guerre du Pays de Meaux in 2011. Also telling is the fact that many museums reworked their permanent exhibitions in time for the centenary of the First World War, for example, the Imperial War Museum (London) or the Museum of Military History (Vienna).

Several large and spectacular exhibitions in Germany at once promoted and attested to a growing public interest in the First World War.[38] The exhibitions were remarkable not only because of their superb objects, but also because of the close cooperation between curators and academics. Education and entertainment were inextricably linked. Historians, moreover, recognized the value of the objects. Where exhibitions can only have an impact for a limited time, the establishment of major new museums starting in the 1990s has been chiefly responsible over the past twenty years for inspiring the most important lines of research and the resurgent interest in the First World War. These museums (with the exception of the Military History Museum in Dresden, the important German museum that deals with war and violence) are located at former battlefields. They incorporate the remaining traces of the conflict, the monuments, and the cemeteries into the interpretation of the events and aim to transform the visitor’s emotions into real insights. Since the vast majority of visitors do not find their way to the museums, a visitor center was built next to the monument of Thiepval in 2004. Other cemeteries/sites of memory, for example, Tyne Cot and Langemarck, followed suit. It is becoming increasingly clear that visitors not only require help interpreting the events, but also merely the opportunity to relax. While twenty years ago many visitors to the battlefields were quite well informed, today they come because they lack knowledge about the war and want to learn something. The need for guidance thus continues to grow.[39] The celebrations have also changed. Instead of putting the veterans center stage, they focus on the youth: In 1996, 2,000 children from Germany and France took part in the eightieth anniversary of the Battle of Verdun, and, in 2009, the European flag was hoisted for the first time.[40]

The Historial de la Grande Guerre opened in the summer of 1992 with tremendous fanfare. After many years of intensive work and in close cooperation with international First World War experts, a museum opened that endeavored to treat the Great War in dialogue with the still-visible traces, monuments, and cemeteries along the Somme. National constraints were unambiguously rejected (which was also a repudiation of the memory celebrated in Verdun from an exclusively French perspective). The museum team also broke new ground in their presentation: instead of recreated trenches and the noises of battle, there was only silence. And the exhibits were shown in open depressions in the floor, without glass coming between the objects and the visitors. Protruding out of the depressions, which simultaneously resemble a trench and a grave, are objects on wire racks that were either made by the soldiers themselves or allowed them to preserve a sense of tranquility and civilian life: musical instruments and drawings. The Historial relates the war from German, French, and British perspectives. In the display cases, objects are shown in three parallel lines. The visitor immediately sees not only the similarities in how the three countries educated people about the war, but also the differences: the German “Reservistenkrug” (reservist tankard) has no equivalent in England, which did not introduce conscription until 1916. The Historial does not seek to replace national memories with a shared European one. Instead, the exhibition organizers are interested in providing room for numerous memories of the First World War to exist side by side, even if they contradict each another.

In the Historial, art has its own space. Alongside soldiers’ drawings, etchings are displayed from the German Otto Dix’s series “The War.” In addition to contemporary (silent) film, the exhibition organizers rely in particular on the power of artistic interpretation.

The Historial and the In Flanders Fields Museum in Ypres both deal with the theme of injury. However, images like those that were only briefly seen after the war in the Berlin anti-war museum of Ernst Friedrich are more brutal than many exhibition organizers would prefer to show. In Ypres, visitors enter small cabinets dedicated to themes of death and injury. Here, the visitor must deliberately direct his gaze upward to view the faces hanging from the ceiling that have been shot apart. The Historial decided against displaying plaster masks of severely injured veterans. In Meaux, visitors are able to explore other ways of becoming familiar with the war. For instance, they can lift a grenade to get a sense of how much physical exertion the conflict demanded of the soldiers. The Military History Museum in Dresden goes one step further: hiding behind a hinged door is a button that the visitor can press to smell the foul odor of explosives, excrement, and rotting flesh. The filth that earlier conservators thoroughly scrubbed from the exhibits has returned to the museum in a rather selective manner. New museums promote current research. As the Historial has done since 1992, they offer a forum for experts and scholarships to support young researchers. In these places, the boundary between popular (i.e., entertaining) memory cultures and didactic scholarship is eliminated. The museums not only provide stimuli for further research, they also find inspiration from outside. And, not least because of strong competition, they are forced to reinvent themselves time and again in relatively short periods of time. In the summer of 2014, the Imperial War Museum opened its new galleries on the First World War to visitors. The exhibition organizers moved away from making a strong emotional appeal and focussing on individual destinies in favor of an intensive analysis of the war’s causes and consequences. The development of new sites under the directors Frankland and Alan Borg continuously expanded the range of subjects. All the conflicts the Empire took part in over the 19th and the 20th century are dealt with, even if with a noticeably stronger emphasis on British history.

The museums have turned more and more into an economic engine. The new museums used public funds to promote above all economically underdeveloped regions (such as along the Somme, but also in Flanders). The history of the First World War is told in several languages, if not from multiple perspectives, not only in Péronne and Ypres, but also in smaller museums dealing with the War in the Alps, e.g., the Museum 1915-1918 in Austria Kötschach-Mauthen, the Kobariški Musej in Slovenia (Kobarid/Caporetto). Images of the enemy no longer play a role in the museums, which is no doubt at least partly due to the fact that tourists from all countries are addressed.[41]

In 2010, the European flag was hoisted in Verdun for the first time. In February 2014, the first panel commemorating a German soldier, Peter Freundl (1895-1916), was placed in the ossuary.[42] In 2014, the public's interest continued to grow. This is not only demonstrated by the rising number of tourists in France and Belgium, but also by the large number of exhibitions and television programs. The route of the Tour de France travelled via Ypres, the Chemin des Dames, and past the Douaumont Ossuary. Commemorations in Liege and Leuven (4 August 2014) and on the Hartmannsweilerkopf (3 August 2014) and the meeting of EU leaders in Ypres (25 June 2014) show that the memory of the First World War is being used by statesmen as an argument for European unity and reconciliation.

In 2015, it became clear that memory of the First World War is not uncontroversial. In Germany, even though German President Joachim Gauck spoke of a genocide of the Armenians in 1915, the Foreign Minister and the Chancellor were nevertheless more cautious in their choice of words with regard to partner nation Turkey. The memory of deserters and soldiers who had been court-martialed and shot - and particularly the issue of their rehabilitation - is a source of conflict in many countries. In 1998, French Prime Minister Lionel Jospin urged granting a place in the official memory for those soldiers who were executed in 1917 for mutiny. President Jacques Chirac categorically rejected the idea of rehabilitating the mutineers.[43] In 2008, near the totally destroyed town of Fleury, President Nicolas Sarkozy erected a monument to French soldiers whose execution was unequivocally a miscarriage of justice. In 1991, President George H.W. Bush posthumously honored the African American soldier Freddie Stowers (1896-1918) with the Medal of Honor, the highest award of the US army. Stower’s grave is located in the magnificent Cemetery Romagne sous Montfaucon. The signature on the gravestone was subsequently highlighted with gold-leaf paint. Sponsorship for the grave was assumed by the travel guide Pierre Lenhard. Without the information he provides, visitors would be able neither to read about nor to comprehend the development over time of Stower’s commemoration.

The former battlefields lend themselves to a continuously renewed understanding of the past. This makes them - together with museums - the most important medium of popular memory today.

Susanne Brandt, Heinrich-Heine-Universität Düsseldorf

Section Editor: Elise Julien

Notes

- ↑ For example: Becker, Jean-Jacques/Krumeich, Gerd: Der Große Krieg. Deutschland und Frankreich im Ersten Weltkrieg 1914-1918, Essen 2010. Hogh, Alexander/Mailliet, Jörg: Tagebuch 14/18. Vier Geschichten aus Deutschland und Frankreich, Bonn 2014. Archaeology as an international or transnational project in: Saunders, Nicolas J.: Killing Time. Archaeology and the First World War, Stroud 2010, p. 2.

- ↑ Denéchère, Bruno/Revillon, Luc: 14–18 dans la bande dessinée. Images de la Grande Guerre de Forton à Tardi, Paris 2008.

- ↑ Duval, Fred/Pécau, Jean Pierre/Mr. Fab: L`Homme de l`année 1917, le soldat inconnu, 2013; Antoni, Stéphane/Ormière, Olivier: Le temps du rêve, 2013; Cruchaudet, Chloé: Das falsche Geschlecht, Berlin 2014.

- ↑ Tardi, Vincent Marie, dir.: La Grande Guerre dans la Bande Dessinée, Péronne 2009, p. 52.

- ↑ Offenstadt, Nicolas: Der Erste Weltkrieg im Spiegel der Gegenwart. Fragestellungen, Debatten, Forschungsansätze, in: Bauerkämper, Arnd/Julien, Elise (eds.): Durchhalten! Krieg und Gesellschaft im Vergleich 1914-1918, Göttingen 2010, pp. 54-77.

- ↑ Jahr, Christoph: Wer fehlt? Etwa Du? in: Die Zeit no. 23 vom 06.15.2014, online: http://www.zeit.de/2014/23/erster-weltkrieg-deserteur-fahnenflucht (retrieved 1 June 2015)

- ↑ Games in the Historial de la Grande Guerre, in: Hadley, Frédérick: Les jeux et jouets de la Grande Guerre 14-18, in: Le Magazine de la Grande Guerre, 50 (2006), Belgique, pp. 70-75. See also: http://www.museedelagrandeguerre.eu/sites/default/files/pdf/2013/Dossier_pedagogique_WarGames.pdf (retrieved 1 June 2015).

- ↑ Figures taken from: Schwarz, A.: Computerspiele – ein Thema für die Geschichtswissenschaft?, in: idem (eds.): Wollten Sie auch immer schon einmal pestverseuchte Kühe auf Ihre Gegner werfen?, Münster et al. 2010, pp. 7-28.

- ↑ Lindner-Wirsching, Almut: Französische Kriegsliteratur, pp. 5f, online: http://www.erster-weltkrieg.clio-online.de/_Rainbow/documents/einzelne/franzkriegsliteratur.pdf (retrieved 28 August 2013).

- ↑ Winter, Jay: The Experience of World War I, London 1989, p. 229.

- ↑ Ossowski, Mirosław: “Es war einmal in Masuren.” Der Erste Weltkrieg in Ostpreußen als Erinnerungsort aus literaturhistorischer Perspektive, in: Störtkuhl, Beate/Stüben, Jens/Weger, Tobias (eds.): Aufbruch und Krise. Das östliche Europa und die Deutschen nach dem Ersten Weltkrieg, München 2010, pp. 165-183, here p. 175f.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 178f.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 182.

- ↑ http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Liste_von_Kriegsfilmen (retrieved 28 August 2013) and http://www.moviepilot.de/filme/beste/zeit-erster-weltkrieg (retrieved 6 June 2015).

- ↑ Cited in: Schneede, Uwe M.: Die Avantgarde und der Krieg. On the visual arts from 1914-1918: http://www.goethe.de/ins/fr/lp/kul/mag/kw1/de12354686.htm (retrieved 4 September 2014).

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Cited in: Iltschenko, Anna: Russische Künstler über den Krieg, in: Online Magazin Deutschland und Russland: http://www.goethe.de/ins/fr/lp/kul/mag/kw1/de13095443.htm (retrieved 2 September 2014).

- ↑ Reconstruire, in: Cabanes, Bruno/Duménil, Anne: Larousse de la Grande Guerre, Paris 2007, pp. 407-413, here p. 412.

- ↑ Frank, Hartmut: Interferenzen Frankreich-Deutschland, Architekturtheorie und Grenzgebiete, online: http://www.ryckeboer.fr/panofrag/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=7&Itemid=11&lang=de (retrieved 22 January 2015).

- ↑ http://www.lochnagarcrater.org (retrieved 2 June 2015).

- ↑ Projet de Loi sur les vestiges et souvenirs de guerre, Chambre des Députés, no. 1579, 11.08.1920, cf.: Brandt, Susanne: Vom Kriegsschauplatz zum Gedächtnisraum: die Westfront 1914-1940, Baden Baden 2000, pp. 132f. See also: Viltart, Franck: Naissance d´un patrimoine: les projets de classement des ruines, vestiges et souvenirs de guerre (1915-1918), in: In situ [En ligne], 23 | 2014. online: http://insitu.revues.org/10990; DOI: 10.4000/insitu.10990 (retrieved 18 August 2015).

- ↑ Krumeich, Gerd: Konjunkturen der Weltkriegserinnerung, in: Rother, Rainer (ed.): Der Weltkrieg 1914-1918. Ereignis und Erinnerung, Berlin 2004, pp. 68-73, here p. 70.

- ↑ Stamp, Gavin: The Memorial to the Missing of the Somme, London 2007, p. 113.

- ↑ Brown, Eric/Cook, Tim: The 1936 Vimy Pilgrimage, in: Canadian Military History, 20/2 (2011), pp. 37-54, here pp. 51f.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 51.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 53.

- ↑ Midgley, David: Trauer, Erinnerung und nationale Identitätsstiftung. Überlegungen zu den Kriegsdeutungen nach 1918 auf deutscher und britischer Seite, in: Pyta, Wolfram/Kretschmann, Carsten (eds.): Burgfrieden und Union sacrée. Literarische Deutungen und politische Ordnungsvorstellungen in Deutschland und Frankreich 1914-1933, Munich 2011, pp. 179-202, here p. 197ff.

- ↑ Scates, Bruce: Return to Gallipoli. Walking the Battlefields of the Great War, Cambridge 2006.

- ↑ Köroğlu, Erol: Taming the Past, Shaping the Future: The Appropriation of the Great War Experience in the Popular Fiction of the Early Turkish Republic, in: Farschid, Olaf/Kropp, Manfred/Dähne, Stephan (eds.): The First World War as Remembered in the Countries of the Eastern Mediterranean, Beirut 2006, pp. 223-230, here p. 230.

- ↑ Beaupré, Nicolas: Ein Jahrhundert später. Der Erste Weltkrieg und die deutsch-französische Aussöhnung (1914-2014): http://www.bpb.de/internationales/europa/frankreich/178119/der-erste-weltkrieg-und-die-deutsch-franzoesische-aussoehnung

- ↑ Brandt, Vom Kriegsschauplatz zum Erinnerungsort 2000, pp. 192ff.

- ↑ http://www.wlb-stuttgart.de/sammlungen/bibliothek-fuer-zeitgeschichte/bestand/geschichte-der-bibliothek-fuer-zeitgeschichte/ (retrieved 29 August 2013).

- ↑ Krumeich, Gerd: Verdun, in: den Boer, Pim/Duchhardt, Heinz/Kreis, Georg (eds.): Europäische Erinnerungsorte 2. Das Haus Europa, Munich 2012, pp. 437-444, here p. 442.

- ↑ Cochet, François: Verdun et la construction de ses mémoires. De la Bataille au Centre Mondiale de la Paix, in: Hudemann, Rainer/Schmeling, Manfred (eds.): Die “Nation” auf dem Prüfstand. La “Nation” en question/Questioning the “Nation”, Berlin 2009, pp. 65-77, here p. 73. See Pierson, Xavier: Le Mémorial de Verdun: “Le Mémorial des Combattants,” in: Guerre et mondiales conflits contemporains, 57/235 (2009), pp. 13-20, here p.15.

- ↑ Sternberg, Claudia: The Tripod in the Trenches. Media Memories of the First World War, in: Korte, Barbara/Schneider, Ralf (eds.): War and the Cultural Construction of Identities in Britain, Amsterdam et al. 2002, pp. 201-223, here p. 209.

- ↑ Ossowski, Mirosław: “Es war einmal in Masuren.” Der Erste Weltkrieg in Ostpreußen als Erinnerungsort aus literaturhistorischer Perspektive, in: Störtkuhl, Beate/Stüben, Jens/Weger, Tobias (eds.): Aufbruch und Krise. Das östliche Europa und die Deutschen nach dem Ersten Weltkrieg, Munich 2010, pp. 165-183, here p. 172.

- ↑ In Germany, it was mainly: “Als der Krieg über uns gekommen war…” Die Saarregion im Ersten Weltkrieg, Saarbrücken 1993; Der Tod als Maschinist. Der industrialisierte Krieg 1914-1918, Osnabrück 1998; Der Erste Weltkrieg 1914-1918. Ereignis und Erinnerung, Berlin 2004.

- ↑ Dendooven, Dominique: Die “Musealisierung” der Landschaft in Westflandern, online: http://www.ryckeboer.fr/panofrag/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=2&Itemid=6&lang=de (retrieved 22 January 2015).

- ↑ Krumeich, Verdun 2012, p. 443.

- ↑ Barth-Scalmani, Gunda: Der Erste Weltkrieg in den Erinnerungslandschaften der Südwestfront, in: Blätter für deutsche Landesgeschichte 143 (2007), pp. 1-32, here p. 25. Idem: The Memory Landscape of the South-Western Front: Cultural Legacy, Promotion of Tourism, or European Heritage?, in: Bürgschwentner, Joachim/Egger, Matthias/Barth-Scalmani, Gunda (eds.): Other Fronts, Other Wars? First World War Studies on the Eve of the Centennial, Leiden 2014, pp. 463-500.

- ↑ http://www.verdun-douaumont.com/ils-sappelaient-peter-et-victor/?lang=de (retrieved 1 June 2015).

- ↑ Edwards, Peter: "Mort pour la France": Conflict and Commemoration in France after the First World War, University of Sussex Journal of Contemporary History 1 (2000), pp. 1-11, here p. 9.

Selected Bibliography

- Barth-Scalmani, Gunda: The memory landscape of the south-western front. Cultural legacy, promotion of tourism, or European heritage?, in: Bürgschwentner, Joachim / Egger, Matthias / Barth-Scalmani, Gunda (eds.): Other fronts, other wars? First World War studies on the eve of the centennial, History of warfare, Leiden; Boston 2014: Brill, pp. 463-500.

- Brandt, Susanne: Vom Kriegsschauplatz zum Gedächtnisraum. Die Westfront 1914-1940, Baden-Baden 2000: Nomos.

- Le Musée de la Grande Guerre. Pays de Meaux. Un nouveau regard sur 14-18, Paris 2011: Cherche midi, 2011.

- Farschid, Olaf / Kropp, Manfred / Dähne, Stephan (eds.): The First World War as remembered in the countries of the Eastern Mediterranean, Beirut; Würzburg 2006: Orient-Institut; Ergon Verlag.

- Fontaine, Caroline (ed.): The collections of the Historial of the Great War, Paris; Péronne 2008: Somology Art Publishers.

- Gilles, Benjamin / Offenstadt, Nicolas: Mémoires de la Grande Guerre, in: Matériaux pour l'histoire de notre temps 113-114/1, 2014, pp. 2-5.

- Gregory, Adrian: The silence of memory. Armistice Day, 1919-1946, Oxford; Providence 1994: Berg.

- Kavanagh, Gaynor: Museums and the First World War. A social history, London; New York 1994: Leicester University Press.

- King, Alex: Memorials of the Great War in Britain. The symbolism and politics of remembrance, Oxford; New York 1998: Berg.

- Korte, Barbara / Paletschek, Sylvia / Hochbruck, Wolfgang (eds.): Der Erste Weltkrieg in der populären Erinnerungskultur, Essen 2008: Klartext.

- Lloyd, David Wharton: Battlefield tourism. Pilgrimage and the commemoration of the Great War in Britain, Australia, and Canada 1919-1939, Oxford 1998: Berg.

- Paris, Michael (ed.): The First World War in popular cinema. 1914 to the present, Edinburgh 1999: Edinburgh University Press.

- Rivé, Philippe / Becker, Annette (eds.): Monuments de mémoire. Les monuments aux morts de la Première Guerre mondiale, Paris 1991: Mission permanente aux commémorations et à l'information historique.

- Rother, Rainer / Herbst-Meßlinger, Karin (eds.): Der Erste Weltkrieg im Film, Munich 2009: Edition Text + Kritik.

- Schneede, Uwe M. / Bundeskunsthalle Bonn (eds.): 1914. Die Avantgarden im Kampf, Cologne 2013: Snoeck.

- Sherman, Daniel J.: The construction of memory in interwar France, Chicago; London 1999: University of Chicago Press.

- Störtkuhl, Beate / Stüben, Jens / Weger, Tobias (eds.): Aufbruch und Krise. Das östliche Europa und die Deutschen nach dem Ersten Weltkrieg, Munich 2010: Oldenbourg.

- Winter, Jay: Sites of memory, sites of mourning. The Great War in European cultural history, Cambridge 2000: Cambridge University Press.