Structure↑

Nearly half of the drama’s dialogues consist of quotations that Karl Kraus (1874-1936) culled from newspaper reports and conversations he overheard on the streets of Vienna and in its cafes, where the public often discoursed. While adhering to certain conventions of classical tragedy, The Last Days - as Kraus himself states in the preface - lacks a tragic hero. Filling its pages, rather, are “operetta figures” and walking newspaper headlines that perform the “tragedy of mankind.”[1] Comprised of 213 scenes and over 500 characters, the drama was not intended to be staged.

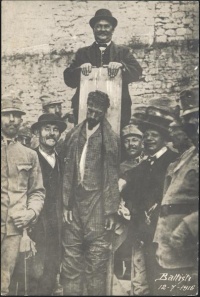

The Last Days can be read as an early work of modernism on a grand scale. Apart from its documentary nature, the play contains elements of photography (including the frontispiece that displays the hanging of Cesare Battisti (1875-1916) and, next to him, his proud executioners), cinema, Expressionism (especially in the series of apparitions in the final scene of Act V), montage, and copious intertextual references.

The Last Days moreover avoids the trajectory of a single narrative, operating primarily according to the principle of recurring motif. Stock characters such as the “Patriot” and the “Subscriber” (to the Neue Freie Presse) appear throughout the drama, but the substance of their dialogues never fundamentally alters. Indeed, very little changes from the beginning to the end, which covers the entire span of the war. Yet the drama does not adhere to a linear chronology: its final words - “This is not what I intended”[2] - uttered by the “Voice of God,” were spoken by Wilhelm II, German Emperor (1859-1941) in 1915 as he witnessed the carnage on the Western Front.

Content↑

The Last Days, which begins with the funeral of Franz Ferdinand, Archduke of Austria-Este (1863-1914) and his wife and ends in a cosmic clash of otherworldly voices, is merciless in its critique of generals, journalists, politicians, bureaucrats, scientists, doctors, priests, poets, financiers, and passers-by: all such figures are revealed to be functionaries in the war machine. But the drama also imbues one of the war’s otherwise silent victims - the natural world - with a voice of its own, including the trees that were felled to produce newspapers and the beasts of burden that toiled under the most brutal of conditions.

One of the play’s characteristic exchanges occurs between Alice Schalek (1874-1956), an actual war correspondent, and an unnamed officer in the southwestern front. Schalek sees the war as an embodiment of a “liberated humanity,”[3] while the officer insists that the soldiers want the war to come to an end; it is Schalek’s sentiments that get published. For Kraus, this type of miscommunication expressed precisely how the war was able to perpetuate itself, despite the protests of even those directly involved. Journalists would publish the lies of those in power, who, in turn, believed them when they appeared in print.

The play contains descriptions of neither gruesome battles nor corpses piling atop one another. The war it articulates, rather, is a war of discourse, in which, to paraphrase Kraus, the spilling of ink leads to the spilling of blood, which turns back into ink.

The “Grumbler”↑

The recurring dialogue between the “Grumbler” (Der Nörgler), Kraus’s fictional alter ego, and the “Optimist,” constitutes the crux of the drama’s political content and the source of its greatest pathos. If the Optimist represents the perspective of respectable bourgeois ideology and press-induced nationalism, the Grumbler is the antidote to this ostensibly innocuous position, which he continuously exposes as internally inconsistent and ultimately violent. In a sense, the Optimist only provides the cues for the Grumbler’s monologues.

In satirical-metaphorical language, the Grumbler parses the fatal combination of idiocy, greed, and callousness with respect to human dignity that has engendered this unprecedented political catastrophe. Claiming to be a patriot of a different sort, the Grumbler finally confesses to his own guilt: he, too, is part of the historical moment to which he can only bear witness. Indeed, his parting words equate the “keynote of the era” with the “echo of [his] bloodstained obsession,”[4] as he pleads for future redemption and for a posterity that will read his text with forbearance, instilling the drama with an unmistakably apocalyptic undertone.

Impact and Afterlife↑

Kraus declared The Last Days to be unfit for the stage and performable only for a “theater on Mars.” Fearing that it would turn into a theatrical spectacle in the wrong hands, he refused directorial requests from both Erwin Piscator (1893-1966) and Max Reinhardt (1873-1943). Kraus himself staged his own performance of the Epilogue in 1923, and throughout the 1920s he gave readings from a stage version of the play that he crafted. The Austrian actor and cabaret performer Helmut Qualtinger (1928-1986) continued this tradition, recording his own readings of the play in the late 1960s and early 1970s. After World War II and up until this day there have been several scenic performances of the play. The first complete French translation of The Last Days was published by Jean-Lous Basson and Henri Christophe in 2004, and the first unabridged English translation was completed by Fred Bridgham and Edward Timms in 2015. Michael Russell also recently published a complete, English-language, online version of the text.

Ari Linden, University of Kansas

Section Editor: Tamara Scheer

Notes

Selected Bibliography

- Kraus, Karl: Die letzten Tage der Menschheit. Tragödie in fünf Akten mit Vorspiel und Epilog, Frankfurt a. M. 1986: Suhrkamp.

- Kraus, Karl: The last days of mankind. The complete text, New Haven 2015: Yale University Press.

- Kraus, Karl, Holzer, Anton (ed.): Die letzten Tage der Menschheit. Der Erste Weltkrieg in Bildern, Darmstadt 2013: Primus-Verlag.

- Lensing, Leo: Moving pictures. Photographs and photographic meaning in Karl Kraus’s The Last Days of Humanity, in: Kuhn, Anna Katharina / Wright, Barbara Drygulski (eds.): Playing for stakes. German-language drama in social context, Oxford; Providence 1994: Berg, pp. 75-100.

- Timms, Edward: Karl Kraus, apocalyptic satirist. Culture and catastrophe in Habsburg Vienna, New Haven 1986: Yale University Press.