What is War Poetry?↑

Reminding us of William Wordsworth's (1770-1850) dictum that "poetry is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings", Jon Stallworthy (1935-2014) asserted that

During the Great War, poetry had a currency that it lacks in the early twenty-first century. Newspapers, magazines, pamphlets, anthologies, and individual collections featured poems by combatants and non-combatants, by men and by women, at "home" or near the front lines. Poetry seemed a natural outlet for the intense emotions generated by the war and its range challenges the concept that only those with direct experience of fighting, i.e. soldiers, were allowed to write about war. The Great War was a total war and no one was left untouched by it. Suffering, mourning, patriotism, pity, and love were universally, if not equally, experienced. Thus "war poetry" is as all-encompassing as total war itself.

Voices↑

Discussions of First World War poetry tend to be dominated by English names: Wilfred Owen (1893-1918), Siegfried Sassoon (1886-1967), Isaac Rosenberg (1890-1918). Where poems are anthologised, they are done so "almost exclusively within a narrow national framework".[2] The canon of English poetry of the First World War represents only a small fraction of verse written and read during and after the war across the combatant nations. Poets with "cosmopolitan sympathies", to quote Isaac Rosenberg, wrestled with the same problem as their less self-consciously literary counterparts: how to represent a global conflict, dominated by modern technology, involving millions of combatants and countless civilians.

The European avant-garde poetic movements of the pre-war years seemed particularly suited to interpret the cataclysm, but traditional verse also continued to place the soldier at the centre of the national, heroic cause.

The German literary scholar Julius Bab (1880-1955) estimated that in August 1914, 50,000 poems were submitted to magazines and newspapers in the first weeks of the war with one Berlin newspaper alone receiving about 500 poems per day. He himself published twelve anthologies between 1914 and 1919 all under the title Der deutsche Krieg im deutschen Gedicht and which culminated in his 1920 bibliography Die deutsche Kriegslyrik, 1914-1918, featuring Soldatendichter (soldier-poets) including Gerrit Engelke (1890-1918) and August Stramm (1874-1915). Die Aktion, with its roots in Expressionism was one of the chief outlets for poetry, publishing such poets as Oskar Kanehl (1888-1914) and Wilhelm Klemm (1881-1968).

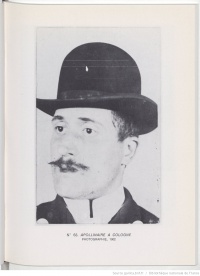

In France, Guillaume Apollinaire (1880-1918) declared that "Cannons are useful only in artillery", resisting the easy classification and restrictions of particular artistic movements, whether it be Futurism or any other avant-garde coterie. His collection, Calligrammes (1918). Poèmes de la paix de la guerre, arose out of his front-line experience. Volumes such as Poèmes d’un Poilu 1914-1915 (1916) by André Martel (1893-1976) and Les Voix de la fournaise. Poèmes d’un Poilu (1916) by Gilles Normand align with the numerous volumes printed in England by "soldier-poets". Post-war collections such as Les Poètes contre la guerre (1920) and Anthologie des écrivains français morts pour la patrie (1924-1926; five volumes), which featured, among others, Charles Péguy (1873-1914), enshrined the nation’s poetic output.

Vittorio Locchi (1889-1917), famous for his blank-verse poem Sagra di Santa Gorizia, which celebrated the Italian victory in August 1917, was hailed as of the poeti-eroei or hero-poets of that country’s experience of the First World War. Of the 2,000 books of homage or opuscoli di necrologia published in Italy as memorials to the Caduti or fallen, twenty-four were devoted to Locchi, who was killed when a submarine torpedoed the troopship he was on while en route to Thessalonika. Such books stand in direct contrast to the work of famous modernists, specifically the Italian Futurists, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti (1876-1944) and Gabriele D'Annunzio (1863-1938). A close friend of Apollinaire who served as an infantryman on the lower Isonzo front 1915-1918, then on the Western Front, Giuseppe Ungaretti’s (1888-1970) collection of war poetry L'Allegria (Joy) (1931) display his French Symbolist roots.

The ANZAC experience, so central to the national imaginaries of both Australia and New Zealand, was formed at Gallipoli. Leon Gellert (1892-1977), perhaps Australia’s best-known poet of the Great War, with his Songs of a Campaign in 1917, Clarence Dennis and his volumes The Songs of a Sentimental Bloke (1915) and The Moods of Ginger Mick (1916), and along with the verse of Andrew Barton "Banjo" Paterson (1864-1941) lay claim to such experience. Only recently have the voices of Turkish poets from the other side of the campaign such as Mehmet Akif Ersoy (1873-1936) and H.S. Gezgin been given comparable attention. This is also true of voices from South-East Asia and the African continent, where poetic form extended beyond the printed text, flowering in aural and oral traditions.

Conclusion↑

A global perspective of First World War poetry – by men and by women composed in diverse languages, from different national perspectives, and on various fronts – provides a basis for a new understanding of how this literary form has enshrined the human experience of 1914-1918, to, as Laurence Cotterell (1917-2001) asserted, help make the "immense agony" of the Great War "just bearable".[3]

Jane Potter, Oxford Brookes University

Section Editor: Emmanuelle Cronier

Notes

- ↑ Stallworthy, Jon: The Oxford Book of War Poetry, Oxford 1984, p. 21.

- ↑ Beaupré, Nicolas: Soldier-Writers and Poets, in: Winter, Jay (ed.): The Cambridge History of the First World War, Cambridge 2014, p. 471.

- ↑ Cotterel, Laurence: Forward, in: Reilly, Catherine W. (ed.): English Poetry of the First World War. A Bibliography, London 1978, p. 5.

Selected Bibliography

- Beaupré, Nicolas: Soldier-writers and poets, in: Winter, Jay (ed.): The Cambridge history of the First World War. Civil society, volume 3, Cambridge 2014: Cambridge University Press, pp. 445-474.

- Cotterel, Laurence: Forward, in: Reilly, Catherine W. (ed.): English poetry of the First World War. A bibliography, New York 1978: St. Martin's Press.

- Das, Santanu (ed.): The Cambridge companion to the poetry of the First World War, Cambridge 2013: Cambridge University Press.

- Stallworthy, Jon: The new Oxford book of war poetry, Oxford 2014: Oxford University Press.