Introduction↑

Australian Great War literature is far less studied and well known than its British counterpart, even in Australia. There is no readily agreed-upon canon of Australian war writing; Australian commemorative liturgy draws on British poet Laurence Binyon’s (1869-1943) “For the Fallen” (1914) and Canadian war poet’s John McCrae’s (1872-1918) “In Flanders Fields” (1915), and frequently soldiers’ letters and diaries, rather than home-grown literary work.

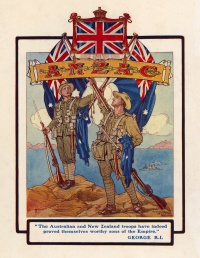

Claiming 62,000 dead, the First World War remains the nation’s costliest overseas conflict. It divided the country deeply and left visible traces on the Australian landscape – countless memorials, large and small. Its most significant legacy is a potent national myth: the Anzac legend (derived from ANZAC, Australian New Zealand Army Corps), a story of courage and mateship, larrikinism and resourcefulness, first played out on Gallipoli, on 25 April 1915, a day that has since become Australia’s de facto national day.

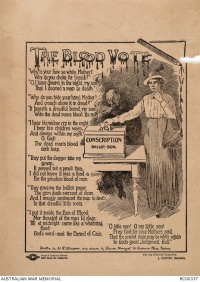

In Australia and New Zealand the word “Anzac” has been protected by law since 1916; its commercial use is tightly regulated. At the war’s end, an Australian reader found it “unfortunate that the exploitation of the war in fiction cannot be forbidden as summarily as are Anzac and other words in trade advertisements.”[1] This comment anticipates the diverse ways in which Australians have engaged imaginatively with that conflict. As this article demonstrates, Australian war writing ranges from depicting the fighting on distant battlefields, to the war experience at home, marked by two divisive conscription referenda, the trauma of grieving loved ones, and the internment of “enemy aliens”. While much discussion of First World War literature limits itself to the war years and the interwar period, this article takes its narrative up to the Centenary. This allows us to see how, through their work, Australian writers have engaged in a debate about the meaning of Australia’s Great War experience, rather than acting as unquestioning commemorators, as some scholars have suggested.

1914-1918: The Pens Enlist↑

The war years marked a high point of reading and writing for Australians, combatant and non-combatant alike. Military authorities, charities, publishers and booksellers were quick to “mobilise” print and discussions of “War Literature” became a staple in Australian newspapers. To a population under strain, reading could offer temporary escape and entertainment. It was a crucial means of keeping informed and connected, and, of making sense of the world at war and Australia’s place in it. Finally, reading and writing could be war work, too – a way of raising money. Opera singer Nellie Melba (1861-1931) invited artists and writers to contribute to Melba’s Gift Book (1915), with all profits donated to the Belgium Relief Fund; royalties from Mary Gilmore’s (1865-1962) The Passionate Heart (1918), a book of poetry, went to the blind.

Poetry held a special place for this generation of Australians. Poems comforted and cajoled; pacified and protested; they found their way into in-memoriam columns and commemorative albums, into concert programs and onto propaganda pamphlets. Collections of soldier poetry include Frank E. Westbrook’s (1889-1976) Anzac and after: A Collection of Poems (1916) and Leon Gellert’s (1892-1977) Songs of a Campaign (1917). Little-known today, Gellert’s volume won a poetry prize from the University of Adelaide and saw five editions by 1918. Illustrated by well-known artist and writer Norman Lindsay (1879-1969), it charts the soldier-speaker’s path from innocence to experience, alongside the poet’s search for adequate lyric form. While the pre-combat poems enlist poetic tradition, the poems from camp register anxieties and uncertainties, often through unanswered questions, and the trench poems are more experimental.[2] “The Husband” ponders the returned man’s profound isolation:

I see a thousand vague and sad tomorrows.

None sees my sadness. No one understands

How I must touch her hair with bloody hands.

Many others were writing from home. Christopher J. Brennan (1870-1932) dedicated his collection A Chant of Doom (1918) to his soldier-brother Philip. Brennan’s fervently patriotic verse, such as his sonnets “Lions of War” and “Kitchener”, demonstrates his skill addressing “a broad contemporary audience, and in meeting the propaganda requirements of the major Sydney newspapers”, where many of these poems first appeared.[3] Australia’s unofficial poet laureate, balladist C.J. Dennis (1876-1938), hit a nerve with his humorous verse novels, written in vernacular slang. The Songs of a Sentimental Bloke (1915)[4] only alludes to the war, with a poem by Belgian poet Léon Montenaeken (1859-1950) on its frontispiece, a tacit expression of solidarity with a besieged nation. “There must be many a Sentimental Bloke… at Gallipoli,” the Bulletin’s reviewer mused, and encouraged instant export of this “most welcome bit of Australia… to the homesick heroes at the Dardanelles.”[5] Angus and Robertson, Dennis’ astute publisher, printed special trench editions, tunic-pocket size. A popular film followed and The Songs of a Sentimental Bloke remains the bestselling book of Australian poetry. Dedicated to “The Boys Who Took the Count”, its sequel, The Moods of Ginger Mick (1916)[6], takes readers to Gallipoli, where Australians from all walks of life become mates: “Shy strangers, till a bugle blast preached ’oly brother’ood;/But mateship they ’ave found at last; an’ they ’ave found it good.” A significant first draft of the Anzac legend, this long poem chronicles the outbreak of the war, Mick’s enlistment and his promotion from the ranks. It celebrates the beautiful Australian spring, with bush birds and golden wattle – all worth fighting for – and mourns Mick’s death, not without enlisting sympathy for his bereft fiancée and other bereaved: “Fer Rose, an’ sich as Rose, when one man dies/It seems the world goes black before their eyes.” Dennis’ achievement lay in “smooth(ing) over deep faultlines and tensions in Australian culture”, argues his biographer.[7] John Le Gay Brereton (1871-1933) and Frank Wilmot (1881-1942) “Furnley Maurice” wrote modernist, pacifist poetry. Mary Gilmore (1865-1962), the first female Australian writer to receive a state funeral, published verse oscillating between pride in soldierly achievement and profound grief over men killed and buried thousands of miles away. Her poem, “The Measure” (1918) asks, “Must the young blood forever flow?/Shall the wide wounds no closing know?” and closes without offering comfort:

Where the swift feet were wont to go;

Closed are the doors that stood so wide---

The white beds empty, side by side.Australian theatres featured a wide array of lectures, pageants, revues, re-enactments, pantomimes and concerts to rally citizens to the cause, fulfilling “the audience’s need for vicarious involvement either by depicting events at the front or by calling for recruits or donations.”[8] Aqua-dramas, adapted from British models, staged the sinking of the German warship Emden, night after night, while performances featuring real soldiers in uniform, for example of O’Leary, V.C., a play now lost, were also popular.

The novel, too, did its bit. Jane Potter has described the publication of popular fiction in wartime Britain as a “profitable enterprise and patriotic contribution.”[9] The same can be said for Australia. New authors such as interim Athenaeum Librarian John Butler Cooper (1862-1951) and Melbourne socialite Mabel Balcombe Brookes (1890-1975) joined seasoned professionals Arthur Wright (1870-1932) and Ambrose Pratt (1874-1944), among others. These early books validate an entire community’s war effort and suffering, often through the frames of popular genre fiction. Wright’s The Hate of a Hun (1916) culminates when its protagonists prevent German spies from blowing up an Australian troopship in Sydney. The heroine of Balcombe Brookes’ On the Knees of the Gods (1918) ultimately overcomes her grief, which the novel depicts with some compassion, and helps the wounded in London. War trilogies for younger readers came from popular children’s writers Mary Grant Bruce (1878-1958) (From Billabong to London, Jim and Wally, and Back to Billabong) and Ethel Turner (1870-1958) (The Cub, Captain Cub, Brigid & the Cub). So eager was Grant to get her protagonists to the front that she enlisted them in a famous British regiment. Turner’s initially reluctant Cub fights with the Australian Imperial Force. Both include opportunities for girls: Grant’s plucky Norah helps stop a German submarine in Ireland, Turner’s Brigid takes care of a Belgian war orphan: “the apprehensive sensitiveness that sometimes displayed itself in this tragic little creature had the power to shake Brigid to the soul.”[10] Reprints and a place in many school libraries helped these books survive well into the 20th century, whereas the early war novels for adult readers quickly faded from view.

Like other troops, Australians produced numerous trench publications. Of these, The Anzac Book (1916) is most famous. Originally conceived as a magazine to raise morale on Gallipoli, it became a souvenir book when the need to evacuate became clear. It was a wartime bestseller, selling over 100,000 copies in Australia alone. Many of the poems, sketches, and stories are humorous: “It is fairly certain,” muses “Private Pat Riot”, “that future historians will teach that Australia was discovered not by Captain Cook, explorer, but by Mr Ashmead Bartlett, war correspondent.”[11] Indeed the book, edited by Charles Bean (1879-1968), commemorates an imperial war effort – its cover sports the Union Jack, its opening words come from General William Birdwood (1865-1951), contributors included New Zealanders and Englishmen, and acknowledged the Indian mule corps, among others.

The Interwar Boom↑

In the interwar years, returned men claimed centre-stage in Australian commemorative culture: major institutions began collecting soldiers’ letters and diaries, and war literature was now often equated with soldierly writing, authenticated by combat experience. Australians found themselves caught up in a “maelstrom of war novels” from overseas, as one commentator put it.[12] And they debated these heatedly, not least through their own war writing.

Expatriate Frederic Manning’s (1882-1935) Her Privates We (1930), originally published as The Middle Parts of Fortune (1929), occupies a tricky middle ground between British and Australian war literature. Its protagonist Bourne is clearly not English, “and felt like an alien” among the men of the British Expeditionary Force; the novel shares with many Australian texts a tendency to seek, and find, some meaning in the horrors of war. Leonard Mann’s (1895-1981) Flesh in Armour (privately published, 1932) revolves around the experiences of three Australian soldiers on the Western Front, who begin to see themselves as distinctly Australian, but whose war experiences differ profoundly, almost as if to anticipate the wide range of responses to the novel itself. While the Bulletin found the book distinctly Australian, a returned soldiers’ magazine called it “too real.” Others were troubled by its anti-imperialism and its frank treatment of sexuality, among them Australia’s major publishing house, Angus & Robertson, which rejected the manuscript.[13] Jack McKinney’s (1891-1966) Western Front novel Crucible (1935) won the novel-writing competition of a major veterans’ association. It uses an episodic narrative style to reflect its protagonist’s efforts to make sense of his war: “The whole thing had just become a monotonous, degrading business. Why were they fighting now?”[14] Novels about Gallipoli were the exception in interwar Australia and came as more up-beat fare. Arthur Crocker’s Australia Hops In (1935), for example, promised readers “to catch the spirit in which Australia entered the conflict... to show... something other than filth and horror only.”[15]

Lead publisher Angus & Robertson issued numerous memoirs throughout the 1930s, such as highly decorated Joseph Maxwell’s Hell’s Bells and Mademoiselles (1932); May Tilton’s nursing account, The Grey Battalion (1933), and J.D. Mitchell’s Backs to the Wall (1937). By far the most commercially successful was Ion Idriess’ The Desert Column: Leaves from the Diary of an Australian Trooper in Gallipoli, Sinai and Palestine (1932). Its countless reprints well into the 1980s helped keep the publisher afloat.

Theatre-goers in interwar Australia were more likely to have heard of English playwright R.C. Sheriff’s (1896-1975) Journey’s End (1928), than of modernist Sidney Tomholt’s (1884-1974) four war plays, which were published, but never staged. Tomholt was a shell-shocked veteran himself; his scripts eerily animate the big war memorials, newly erected in 1930s Melbourne and Sydney, with casts of dead and wounded soldiers. Indebted to European expressionism and symbolism, these works departed too radically from then dominant theatrical practice.[16]

Ups and Downs Post-1945↑

Books about the Second, rather than the First World War dominated the 1950s and 60s, unsurprisingly. Katharine Susannah Prichard’s (1883-1969) Golden Miles (1948) and Judah Waten’s (1911-1985) The Unbending (1954) were bold attempts, by two well-known Australian Communist writers, to reconfigure Australia’s story of the First World War along lines of class rather than nation, just as the Cold War was heating up: “That which is good for the working class I esteem patriotic,” says one of Waten’s characters.[17] Both hone in on the fiercely divisive conscription referenda. Martin Boyd’s (1893-1972) When Blackbirds Sing (1962) is the last novel by a returned man and reworks the author’s experiences on the Western Front and in England. All three struggled for readers: Waten’s novel, written with funding from the Australian government, caused a scandal for its celebration of the Industrial Workers of the World as the war’s true heroes.[18]

Peter Weir’s Gallipoli (1981) is often considered a central Great War narrative that resonated in a post-imperial, post-Vietnam Australia, but it was flanked by significant novels that challenged that film’s easy assumptions about Australian innocence lost on European battlefields. Roger McDonald’s modernist 1915 (1979) and David Malouf’s poetic Fly Away Peter (1982) both remain in print, unlike Geoff Page’s important home front novel, Benton’s Conviction (1985). Gwen Kelly’s Always Afternoon (1981) and Joan Dugdale’s Struggle of Memory (1991) revisit the traumatic experiences of interned Germans in Australia. Brenda Walker’s The Wing of Night (2005) returns to the Western Australia of Weir’s film to focus on the grieving women eclipsed by David Williamson’s script, while John Charalambous Silent Parts (2006, repr. An Accidental Soldier) and Peter Yeldham’s Barbed Wire and Roses (2007) are Antipodean responses to Sebastian Faulks’ Birdsong (1993). Like Faulks’ novel, which had a significant reception in Australia, both feature family historians, but their research leads them to deserters rather than the men enshrined in collective memory and raises more prickly questions about the possibilities of recuperating the past.

100 Years On↑

Australia spent more money on the Centenary of the First World War than any other nation: 600 million Australian dollars. In 2015, “Spirit of the Anzacs”, a charity single produced by country-singer Lee Kernaghan and others, proclaimed that “The spirit of the Anzacs, proud and strong, … will live on and on and on.” This is by no means commemorative consensus, however. In 2012, Tom Keneally, one of Australia’s best-loved writers, voiced the hope that “no one says ‘Australia was born at Gallipoli’… there needs to be a certain amount of de-mythologising.”[19]

The centenary has seen a war books boom: journalist historians such as Peter FitzSimons, Paul Ham and Patrick Lindsay command a large share of this market, but a range of reprints alongside numerous new novels means that Australians can now revisit their First World War through a diversity of materials that is probably unprecedented. Reissues include soldiers’ novels such as Martin Boyd’s When Blackbirds Sing, Leonard Mann’s Flesh in Armour, and for the first time since 1935, Jack McKinney’s Crucible (if only in electronic form). Even wartime bestsellers have resurfaced, in a curious blend of war book and commemorative souvenir: The Anzac Book was lavishly reprinted, and C.J. Dennis’ hugely popular verse novels are available in facsimile pocket-editions for the trenches.

Written at a time when significant numbers of Australians are returning severely damaged from Iraq and Afghanistan, Tom Keneally’s Daughters of Mars (2012) keeps Gallipoli at arm’s length, evoking the peninsula and its battles through the windows of the hospital ships, the wounded bodies of the men, and the struggles of the nurses. Joanne van Os’ Ronan’s Echo (2014) and Pamela Hart’s The Soldier’s Wife (2015) are works of popular fiction that are more disturbing than their nostalgic covers might suggest: both narrate how violence and destruction spill from foreign battlefields into Australian homes when the men return from the war. Bruce Scates’ On Dangerous Ground: A Gallipoli Story (2012) and Chinese-Australian writer’s Ouyang Yu’s Billy Sing (2017) ask probing questions about memory and remembrance: “Think of how many died in the war,” teases Chinese-Australian sniper Billy Sing. “What for? Just so that their memory lives? Where does it live and how long does it last?”[20]

The re-enactment of the departure of the first convoy of Australian and New Zealand troops from Albany/Western Australia on 1 November 2014 might be considered a giant, life-size aqua-drama. An important new play is Tom Wright’s Black Diggers (2014), which premiered in Sydney in 2014, directed by Wesley Enoch, a Noonuccal Nuugiman, before touring nationally. Its sixty scenes move back and forth in time to offer what Enoch describes as “a fragmented view of history.”[21] The action begins in 1880s Queensland, with settler violence against Indigenous people, bringing into conversation two strands of Australian history often seen as competing, rather than entangled with, each other.

Conclusion↑

Historians of literature have traditionally sought to demonstrate literature’s resourcefulness in the face of stress and upheaval, to anticipate and even drive change. In this context, as Kate McLoughlin puts it, “war, as a subject, is the greatest test of the writer’s skills of evocation.”[22] For the First World War, in the English-speaking world, the most compelling account of this test remains combatant-critic’s Paul Fussell’s (1924-2012) The Great War and Modern Memory (1975), a book that struck a chord with Australian scholars such as Robin Gerster and more recently Clare Rhoden, film-maker Peter Weir and novelist Roger McDonald, among others.

Much of Australia’s war literature is poorly remembered, as is the case for similar work around the world. Work that explores what it means to grow up with the legacies of Anzac has fared much better: Geoff Page’s poem “Smalltown Memorials” (1975)[23] is frequently anthologised and has featured in documentaries and museum displays; Alan Seymour’s (1927-2015) play The One Day of the Year (1958/1960) and George Johnston’s (1912-1970) novel, My Brother Jack (1964) remain dear to many Australians.

Nor is Anzac the only frame through which these works make sense of Australia’s war. Over the past 100 years, “war literature” has proven to be a capacious and dynamic term in Australia. To review some of it, as this article has done, is to observe one of the world’s most vibrant commemorative cultures in conversation about its First World War, and its own place in the world. This conversation reveals a range of views. While it has changed over time, it has also been in constant tension with itself. One hundred years later, this debate is on-going, and the meaning of Australia’s Great War experience by no means settled.

Christina Spittel, University of New South Wales

Section Editor: Peter Stanley

Notes

- ↑ Penn, J.: Literary Letter: A Chat on Books. The Register (Adelaide), 16 November 1918, p. 4.

- ↑ Wieland, James: Leon Gellert's Songs of a Campaign: Reading an Un-read Poem, Southerly 52/2 (1992), p. 97.

- ↑ Lynch, Andrew: C.J. Brennan’s A Chant of Doom: Australia's Medieval War, Australian Literary Studies 23/1 (2007), pp. 49-62, p. 49.

- ↑ http://adc.library.usyd.edu.au/data-2/densong.pdf

- ↑ Quoted in Featherstone, Simon: Colonial Poetry of the First World War. In: Das, Santanu (ed.): The Cambridge Companion to the Poetry of the First World War. Cambridge 2013, p. 177.

- ↑ http://setis.library.usyd.edu.au/ozlit/pdf/denmood.pdf

- ↑ Butterss, Phil: An Unsentimental Bloke: The Life and Work of C J Dennis, Kent Town, South Australia 2014, p. 83.

- ↑ Cullen, Susan: Australian Theatre During World War One, in: Australasian Drama Studies 17 (1990), pp. 157-181, p. 160.

- ↑ Potter, Jane: Boys in Khaki, Girls in Print: Women's Literary Responses to the Great War, 1914–1918, Oxford 2005, p. 148.

- ↑ Turner, Ethel: The Cub. London 1915, p. 181.

- ↑ Private Pat Riot: The Raid on London, in: The Anzac Book. London 1916, p. 143.

- ↑ O., J. W.: All Quiet, in: The Black Swan: The Magazine of the Guild of Undergraduates of the University of Western Australia 14/1 (1930), p. 32. Quoted in Spittel, Christina: ‘A Portable Monument?’ Leonard Mann's Flesh in Armour and Australia's memory of the First World War, in: Book History 14 (2012), p. 192.

- ↑ See Spittel, ‘A portable monument?’ 2012, p. 198.

- ↑ McKinney, Jack: Crucible. Sydney 1935, p. 201.

- ↑ Crocker, Arthur: Preface, in: Australia Hops In, Sydney 1935.

- ↑ Kelly, Veronica: Spatialising the Ghosts of Anzac in the Plays of Sydney Tomholt: The Absent Soldier and the War Memorial, Australian Literary Studies 23/1 (2007), pp. 18-35.

- ↑ Waten, Judah: The Unbending. Melbourne 1954, p. 215.

- ↑ For a detailed account of the novel’s Cold War reception, see Carter, David: A Career in Writing: Judah Waten and the Cultural Politics of a Literary Career, Toowomba 1997, pp. 73-99.

- ↑ Marks, Kathy: Thomas Keneally: ‘I hope no one says Australia was born at Gallipoli’, in: The Guardian, online: http://www.theguardian.com/culture/australia-culture-blog/2014/feb/18/thomas-keneally-we-should-apologise-ghosts-wwi-soldiers-wronged (retrieved 1 August 2018).

- ↑ Yu, Ouyang: Billy Sing. Melbourne 2017, p. 92.

- ↑ Enoch, Wesley. Foreword. In: Wright, Tom: Black Diggers, Sydney 2015, p. 5.

- ↑ McLoughlin, Kate: Authoring War: The Literary Representation of War from the Iliad to Iraq, Cambridge 2011, p. 9.

- ↑ https://www.poetrylibrary.edu.au/poets/page-geoff/smalltown-memorials-0439009

Selected Bibliography

- Butterss, Philip: An unsentimental bloke. The life and work of C. J. Dennis, Kent Town 2016: Wakefield Press.

- Caesar, Adrian: 'Kitch' and imperialism. The Anzac Book revisited, in: Westerly 40/4, 1995, pp. 76-85.

- Caesar, Adrian: National myths of manhood. Anzacs and others, in: Bennett, Bruce / Strauss, Jennifer (eds.): The Oxford literary history of Australia, Melbourne; Oxford 1998: Oxford University Press, pp. 147-165.

- Cullen, Sue: Australian theatre during World War One, in: Australasian Drama Studies 17, 1990, pp. 157-181.

- Featherstone, Nigel: Colonial poetry of the First World War, in: Das, Santanu (ed.): The Cambridge companion to the poetry of the First World War, Cambridge 2013: Cambridge University Press, pp. 173-184.

- Gerster, Robin: Big-noting. The heroic theme in Australian war writing, Carlton 1987: Melbourne University Press.

- Holbrook, Carolyn: Anzac. The unauthorised biography, Sydney 2014: NewSouth Publishing.

- Holloway, David: Dark Somme flowing. Australian verse of the Great War, 1914-1918, Malvern 1987: Andersen.

- Kelly, Veronica: Spatialising the ghosts of Anzac in the plays of Sydney Tomholt. The absent soldier and the war memorial, in: Australian Literary Studies 23/1, 2007, pp. 18-35.

- Laugesen, Amanda: 'Boredom is the enemy'. The intellectual and imaginative lives of Australian soldiers in the Great War and beyond, Burlington 2012: Ashgate.

- Niall, Brenda Mary: Seven little billabongs. The world of Ethel Turner and Mary Grant Bruce, Clayton 1979: Melbourne University Press.

- Rhoden, Clare: The purpose of futility. Writing World War I, Australian style, Crawley 2015: UWA Publishing.

- Rutherford, Anna / Wieland, James (eds.): War. Australia's creative response, St. Leonards 1997: Allen & Unwin.

- Schultz, Julianne / Cochrane, Peter (eds.): Griffith review 48. Enduring legacies, Melbourne 2015: Text Publishing.

- Seal, Graham Patrick: The soldiers' press. Trench journals in the First World War, Basingstoke 2013: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Sharkey, Michael: But who considers woman day by day? Australian women poets and World War I, in: Australian Literary Studies 23/1, 2007, pp. 63-78.

- Spittel, Christina: Remembering the war. Australian novelists of the interwar years, in: Australian Literary Studies 23/2, 2007, pp. 121-139.

- Spittel, Christina: So homesick for Anzac? Australian novelists and the shifting cartographies of Gallipoli, in: Ariotti, Kate / Bennett, James E. (eds.): Australians and the First World War. Local-global connections and contexts, Cham 2017: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 203-220.

- Wieland, James: Leon Gellert's songs of a campaign. Reading an un-read poem, in: Southerly 52/2, 1992, pp. 82-98.