Introduction↑

In 1914 Australia was one of the most progressive democracies in the world. Like New Zealand, all Australian women and men had the right to vote – though unlike New Zealand, where Maori were an integral part of the political system, few Australian Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders at this time were on the electoral roll and therefore eligible to cast a ballot. What set Australia apart from other democracies was the success of its labor party which originated in the 1890s as the political offshoot of the trade union movement. In 1899 the self-governing colony of Queensland made history with the world’s first – though short-lived – labor government.[1]

The six self-governing Australian colonies federated to form the Commonwealth of Australia in 1901. The colonies, now renamed states, transferred certain specific responsibilities, such as defense and immigration, to the federal government, but they had retained all other powers for themselves. Section 87 of the Australian Constitution required three-quarters of Commonwealth revenue to be returned to the states for the first ten years of federation, ensuring the balance of power remained with the states.

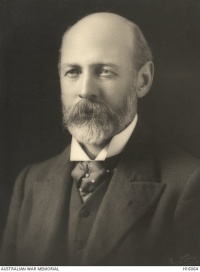

As Australia was part of the British Empire, supreme power was vested in the Crown, the monarch acting on the advice of the United Kingdom’s prime minister. The Crown’s representatives in Australia were the six state governors and the Governor-General of the Commonwealth of Australia, Sir Ronald Munro Ferguson (1860-1934), a Scottish Liberal politician and former army officer.

In the 1890s, the two main political parties were supporters of free trade or tariff protection. The increasing success of the Australian Labor Party, and its gaining of government in the Commonwealth Parliament in 1904 and 1907-1908, forced the Free Traders and Protectionists in 1909 to unite to form the Liberal Party.

The Labor federal election victory in 1910 was a turning point in Australian politics. For the first time, one party had the majority in both the House of Representatives and the Senate. As well, Section 87 of the Constitution that transferred most revenue to the states expired in 1910, meaning more funds for the federal government. Labor instituted an ambitious legislative program that included establishing the government-owned Commonwealth Bank, beginning work on a transcontinental railway linking Western Australia with the eastern states and introducing maternity allowances and old-age pensions. Labor also increased defense spending in 1913 to almost 29 percent of the federal budget. Fears that Japan, following its victory over Russia in 1905, might use its naval and military strength to force Australia to cease its restrictions on Asian immigration – the “White Australia Policy” – led Labor to establish a compulsory military training scheme for males aged twelve to twenty, open a rifle factory, and establish the Royal Australian Navy and the Australian Flying Corps. When British Foreign Secretary Sir Edward Grey (1862-1933) told the 1911 Imperial Conference of the decline in relations with Berlin, Labor authorized planning for an Australian expeditionary force in the event of war with Germany.

1914: War and Election↑

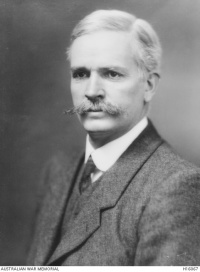

The Liberal Party led by Joseph Cook (1860-1947) had defeated Andrew Fisher (1862-1928) and the Labor Party in the federal election on 31 May 1913 by the narrowest of margins: a majority of one in the House of Representatives. Labor retained its Senate majority, so after a year of deadlock, Cook called an early election to be held on 5 September 1914.

On 4 August the United Kingdom declared war on Germany. As part of the British Empire, the Australian government had no choice about being at war, but they could – and did – choose the extent to which they participated in the conflict. Cook had been busy electioneering as the international situation deteriorated. Munro Ferguson had intervened by suggesting Cook hold a cabinet meeting to decide what contribution Australia would make in the event of war. Cook had announced on 3 August that the government would offer the British 20,000 soldiers and the Royal Australian Navy.[2]

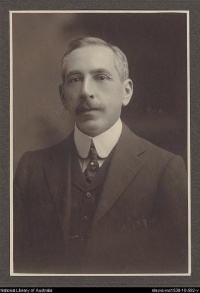

The 5 September election resulted in a convincing Labor victory. Fisher returned with an experienced ministry including William Hughes (1862-1952) as Attorney-General and Senator George Pearce (1870-1952) as Defence Minister. The small Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force gained the surrender of German New Guinea on 17 September. On 1 November the convoy carrying the main Australian Imperial Force (AIF) and the New Zealand Expeditionary Force (NZEF) departed Western Australia and landed its troops in Egypt in December.

The main opposition to the war in 1914 came from radical left known as the “Industrialists,” but they were a small minority. At the time, most Australians and their parliamentary representatives supported the war. Journalists complained that the bipartisan attitudes of Labor and Liberal made it hard to write interesting political reports.[3]

1915: Labor Dominance↑

In 1915 Labor became the dominant party in Australian state and federal politics. In August 1914 Labor was in government in New South Wales, Tasmania, and Western Australia, while the Liberals held the federal government, Queensland, South Australia, and Victoria. Labor won the federal election in September 1914 and retained government in Western Australia in October, while the Liberals kept government in Victoria in November. In 1915 Labor defeated the Liberals in South Australia in March and in Queensland in May. With this, Labor held government in every state and federal parliament except Victoria.[4]

Despite Labor’s electoral dominance, internal party disputes increased in reaction to the economic effects of the war. In Queensland, the price of flour doubled in a year. A referendum bill to give the federal government the power to control prices was introduced to parliament. However, the proposal was opposed by the Labor premiers in New South Wales and Queensland and the powerful Queensland branch of the Australian Workers’ Union. When Hughes became prime minister in October, following Fisher’s resignation due to ill-health, he abandoned the referendum. This was a pragmatic decision – the referendum had been put to the people and defeated twice before, and it was unlikely to succeed a third time – but the decision lost Hughes support within the labor movement.[5]

1916: The Labor Split and Conscription↑

Hughes visits the United Kingdom↑

The new prime minister, with the permission of caucus (the Labor party room), departed for the United Kingdom in January 1916 to discuss political and economic issues with the British government. Hughes succeeded in persuading the British to purchase large quantities of Australian wheat, wool, and metals and he returned to Australia to great acclaim in August 1916.[6]

Conscription had become a major issue during the prime minister’s absence. The Defence Act permitted men to be conscripted for military service within Australia, but not for overseas service. Conscription had been introduced in Britain and New Zealand in the first half of 1916. Australian voluntary recruitment declined during the year and was not replacing the soldiers being killed and wounded on the Western Front.[7]

First conscription referendum↑

Hughes decided that Australia needed to introduce conscription for overseas service to ensure a steady stream of recruits. Hughes could not pass a bill in parliament to bring in conscription because a majority of Labor senators were against conscription. Instead, caucus agreed by a narrow margin to hold a referendum on conscription on 28 October 1916.[8]

The “no” campaign was led by trade unions and the majority of Labor MPs. The “yes” campaign was led by Hughes and his small number of Labor supporters, the Liberal Party, businessmen, and most Church leaders.[9] The referendum was defeated by a narrow margin: 72,476 votes out of 2,247,590 votes cast. Joan Beaumont provides the best assessment of the referendum vote that can be made on the available evidence, arguing Australians “voted in ways that reflected their class, religion and gender, with class perhaps the dominant variable.”[10]

The Labor split↑

When Caucus met on 14 November, Hughes and twenty-three supporters walked out of the party room to pre-empt being expelled from the Labor Party. Frank Tudor (1866-1922) became the new Labor leader. The Labor split was probably inevitable. It reflected the divergence between Hughes and others of the older generation, more moderate in politics and more often British-born, and a younger generation, more radical, more socialist, and more likely local-born. The split affected the state Labor parties in different ways. In Queensland, all Labor ministers opposed conscription except one minister, and Labor retained power. In New South Wales, all Labor ministers supported conscription except one minister, and a coalition was formed with the Liberal Party.[11]

1917: Strikes and Conscription↑

Forming the Nationalist Party↑

Hughes and his colleagues, who now called themselves the “National Labor Party,” needed to form a coalition with the Liberal Party to retain government. Cook proposed an all-party coalition government, but the Labor Party rejected it. Instead, Hughes and Cook created the Nationalist Party. Hughes got the better of Cook in the negotiations, gaining an agreement to have four National Labor ministers and four Liberal ministers, even though the Liberal Party had more MPs. The new government was announced on 17 February 1917.[12]

1917 election↑

Labor retained its majority in the Senate and could block nationalist legislation. Hughes called an election for 5 May 1917 in the hope of gaining a Senate majority. He stated his policy was “to do all in Australia that will aid the Empire and the Allies to win the war.” Hughes sought to neutralize conscription as an election issue by stating that he accepted the referendum vote, and would only hold a second conscription referendum if the war turned against the Allies. Tudor believed that the success of the “no” vote in the conscription referendum would be repeated with a Labor victory in the election. Instead, the Nationalists had success and gained majorities in both houses of parliament.[13]

Strikes↑

The Australian labor movement became radicalized during the Great War in response to “war weariness,” economic difficulties, and specific industrial issues. The “great strike” of August-September 1917, involving 70,000 workers in a range of industries, began as a protest at the introduction of a card system to log the working hours of Sydney tram mechanics. The strike continued for five weeks and the dismissal or demotion of strikers caused ongoing resentment.[14]

Second conscription referendum↑

In October 1917, Hughes announced that a second conscription referendum would be held on 20 December. Why Hughes decided to re-visit conscription is unclear. It is true that the war situation had deteriorated. Russia had left the war; the defeat at Caporetto suggested Italy might do the same. However, it is possible Hughes called the referendum in order to ensure the support of key Liberals such as Cook and William Alexander Watt (1871-1946) rather than in the belief the vote would succeed. The second conscription campaign was more bitter due to the recent strikes and the lists of Australian casualties from the Battle of Passchendaele. The proposition was again voted down, with a larger margin than in 1916. Hughes resigned as prime minister, as he had promised he would do if the referendum failed. Munro Ferguson accepted the resignation, met with Tudor, Cook and some other MPs, and then recommissioned Hughes as Prime Minister.[15]

1918: Negotiated Peace and the Country Party↑

Labor and negotiated peace↑

On 4 April 1918, as German soldiers were advancing across northern France, Federal Labor MP William Higgs (1862-1951) put forward a motion calling for peace negotiations to end the war. The motion was defeated in both the House of Representatives and the Senate. However, Labor Party members and unionists during 1918 increasingly supported a negotiated peace and increasingly opposed recruiting for the AIF. The Labor Interstate Conference in June 1918 threatened a second party split over support for recruiting. The compromise solution was to put the question to a ballot of party members. Counting the postal votes began in early November and the initial numbers were against support for recruiting. By this stage the war had turned in the Allies’ favor. The Labor Federal Executive slowed the count and then abandoned it when the armistice was signed on 11 November.[16]

Hughes visits the United Kingdom↑

Hughes arrived in London on his second prime ministerial visit in June 1918 and joined other Dominion prime ministers in the Imperial War Cabinet. Hughes and Canadian Prime Minister Robert Borden (1854-1937) gained the support of David Lloyd George (1863-1945) to end the cumbersome system of Dominions communicating with the British government through the colonial secretary and the governor-general. Instead Dominion prime ministers now would communicate directly with the British prime minister. Hughes remained in Europe to witness the end of the Great War and represent Australia at the Paris peace conference.[17]

Country Party↑

“Country” candidates, backed by organizations such the Victorian Famers’ Union (VFU), standing in elections under the existing “first-past-the-post” voting system would split the non-Labor vote between Nationalist and “country” candidates and could advantage the Labor Party. J.J. Hall (1884-1949), VFU General Secretary, wrote to Hughes in January 1918 calling for the introduction of preferential voting in which the allocation of preferences would enable the non-Labor vote to be combined. Preferential voting in federal elections came into effect on 25 November 1918. A month earlier Labor had won a seat in a Western Australian by-election with only 34 percent of the vote because the non-Labor vote had been split. On 14 December, the first federal by-election under preferential voting was held in the Victorian seat of Corangamite. When preferences were distributed, the VFU candidate, W.G. Gibson (1869-1955) emerged as the victor, becoming the first “country” MP elected to the Federal Parliament.[18]

1919: Election and the New Political Order↑

Hughes returned to Australia with a shipload of AIF soldiers on 23 August 1919. He decided to take advantage of the favorable political conditions and call an early federal election for 13 December. The Labor campaign was affected by lack of funds (due to the costs of the conscription referendum campaigns and supporting striking workers) and tensions between the existing Labor leader Tudor and Thomas Joseph Ryan (1876-1921), the popular Queensland premier who was entering federal politics. The Country Party, contesting its first election under this name, gained eleven seats. Hughes and the Nationalist Party no longer had an absolute majority in the House of Representatives and were reliant on Country Party support to pass legislation. At the next election on 16 December 1922, the Country Party won more seats and held the balance of power in the House. Earle Page (1880-1961), the Country Party leader, offered to form a coalition with the Nationalists – but only if Hughes was removed as prime minister and replaced by the treasurer, Stanley Melbourne Bruce (1883-1967). Hughes was sacked and Bruce became prime minister.

Conclusion↑

Hughes’ career demonstrates the impact of the Great War on Australian politics. When Hughes became prime minister at the end of 1915, the Labor Party dominated Australian state and federal politics. During 1916, the economic and social strains of the war divided Labor and caused the party to split at the end of the year on the issue of overseas conscription. Hughes was vilified by Labor as a “rat,” but he formed a coalition with the Liberal Party and retained power. His demise following the 1922 election was not caused by Labor, but by the Country Party, a product of increasing farmer dissatisfaction with wartime controls on agriculture that led to the Liberal/Nationalist Party dividing on urban/rural lines. Labor would be the biggest loser in Australian politics in the Great War. It would have some success in state politics in the interwar period, but formed federal government only once, from 1929 to 1931, in the twenty-four-year period between 1917 and 1941.[19]

John Connor, University of New South Wales

Section Editor: Peter Stanley

Notes

- ↑ Bongiorno, Frank: The origins of Caucus: 1856-1901, in: Faulkner, John/Macintyre, Stuart (eds.): True Believers: The Story of the Federal Parliamentary Labor Party, Sydney 2001, pp. 6, 9, 13.

- ↑ Connor, John/Stanley, Peter/Yule, Peter: The War at Home. Melbourne 2015, pp. 81, 85.

- ↑ Smith, A.N.: Thirty Years: The Commonwealth of Australia 1901-1931, Melbourne 1933, pp. 149; Connor/Stanley/Yule, War at Home 2015, pp. 86-90, 92-93.

- ↑ Connor/Stanley/Yule, War at Home 2015, pp. 94-95.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 91, 93-94.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 44-49.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 102-105.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 106.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 110-112.

- ↑ Beaumont, Joan: Broken Nation: Australia in the Great War, Sydney 2015, p. 224.

- ↑ Fitzhardinge, L.F.: The Little Digger 1914-1952. William Morris Hughes: A Political Biography. Volume 2, Sydney 1979, pp. 229-231; Connor/Stanley/Yule, War at Home 2015, p. 118.

- ↑ Connor/Stanley/Yule, War at Home 2015, pp. 116-117.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 119-120.

- ↑ Bollard, Robert: In the Shadow of Gallipoli: The Hidden History of Australia in World War I, Sydney 2013, pp. 111-40; Connor/Stanley/Yule, War at Home 2015, pp. 70-72; Fahey, Charles/Lack, John: The Great Strike of 1917 in Victoria: Looking Fore and Aft, and from Below, in: Labour History 106 (2014), pp. 69-97.

- ↑ Connor/Stanley/Yule, War at Home 2015, pp. 121-127.

- ↑ Connor/Stanley/Yule, War at Home 2015, pp. 134-135.

- ↑ Bridge, Carl: William Hughes Australia. London 2011, pp. 77-96; Connor/Stanley/Yule, War at Home 2015, pp. 135-136, 139-40.

- ↑ Graham, B.D.: The formation of the Australian Country Parties, Canberra 1966, p. 121; Connor/Stanley/Yule, War at Home 2015, pp. 137-138.

- ↑ Connor/Stanley/Yule, War at Home 2015, p. 143.

Selected Bibliography

- Bastian, Peter: Andrew Fisher. An underestimated man, Sydney 2009: UNSW Press.

- Beaumont, Joan: Broken nation. Australians in the Great War, Crow's Nest 2013: Allen & Unwin.

- Bollard, Robert: In the shadow of Gallipoli. The hidden history of Australia in World War I, Sydney 2013: NewSouth Publishing.

- Bridge, Carl: William Hughes. Australia, London 2011: Haus Publishers.

- Connor, John: Anzac and empire. George Foster Pearce and the foundations of Australian defence, Cambridge; New York 2011: Cambridge University Press.

- Connor, John / Yule, Peter / Stanley, Peter: The centenary history of Australia and the Great War. The war at home, volume 4, Melbourne 2015: Oxford University Press.

- Crowley, Frank K.: Big John Forrest, 1847-1918. A founding father of the Commonwealth of Australia, Nedlands 2000: University of Western Australia Press.

- Cunneen, Christopher: Kings' men. Australia's governors-general from Hopetown to Isaacs, Sydney; Boston 1983: G. Allen & Unwin.

- Day, David: Andrew Fisher. Prime minister of Australia, Pymble 2008: HarperCollins.

- Dyrenfurth, Nick: Heroes and villains. The rise and fall of the early Australian Labor Party, North Melbourne 2011: Australian Scholarly Publishing.

- Faulkner, John / Macintyre, Stuart (eds.): True believers. The story of the federal parliamentary Labor Party, Crows Nest 2001: Allen & Unwin.

- Fitzhardinge, L. F.: The little digger 1914-1953. William Morris Hughes. A political biography, volume 2, London 1979: Angus & Robertson.

- Graham, Bruce Desmond: The formation of the Australian Country Parties, Canberra 1966: Australian National University Press.

- Hogan, Michael (ed.): The first New South Wales labor government, 1910-1916. Two memoirs. William Holman and John Osborne, Sydney 2005: University of New South Wales Press.

- McMullin, Ross: The light on the hill. The Australian Labor Party, 1891-1991, Oxford; New York 1991: Oxford University Press Australia.

- Murdoch, John: Sir Joe. A political biography of Sir Joseph Cook, London 1996: Minerva.

- Murphy, Denis J.: T. J. Ryan. A political biography, St. Lucia 1975: University of Queensland Press.