Introduction↑

Until recently, Polish historiography in the field of First World War studies concentrated on the war’s political and military aspects, delineating the "road map" that led to Poland’s reestablishment. The classical studies on Poland and the Polish cause in the years 1914 to 1918 were first published in the 1960s and 1970s and are now outdated.[1] This article presents the main developments that took place in the Polish territories during the First World War. In the last two decades there has been a rise in interest in First World War studies and a parallel departure from the traditional research perspective, as historians have attempted to examine neglected fields, such as the social, cultural, economic, and gender aspects of occurrences between 1914 and 1918.[2] The text is organized chronologically and deals with the situation in the three areas of divided Poland.

Political Situation in the Polish Territories before the War↑

At the beginning of the 20th century, the political status of the territories inhabited by the Poles differed greatly. Due to the partition of Poland at the end of the 18th century, Poles lived in three different states under varying political, social, economic, and cultural conditions on the eve of the Great War. In Russian-Poland, also called Congress-Poland, authorities conducted a process of Russification. The Polish language was not allowed in the public sphere, including in contact with authorities.[3]

Many Poles who did not want to submit to these conditions moved to Galicia, also referred to as Austrian-Poland, where the political atmosphere was completely different. Poles living under Francis Joseph I, Emperor of Austria (1830-1916) were in a much better position than their compatriots in Russian-Poland, subjects of Nicholas II, Emperor of Russia (1868-1918). Since 1860, Galicia had enjoyed extensive political and cultural autonomy, with a local parliament in Lviv (Lwów), municipal corporations, and guaranteed citizens’ rights such as freedom of press, speech, and demonstration, and the right to establish political parties. Administrative, education, and judicial systems were polonized. Polish culture flourished and was able to develop without any political obstacles. Poles enjoyed a privileged status, both politically and economically dominating other ethnic and religious groups such as the Ruthenians/Ukrainians and the Jews, who together made up more than half the population of Galicia.[4]

The harshest restrictions placed upon Polish national life occurred in Prussian-Poland, where a ruthless process of Germanization was conducted. The Polish language was forbidden in the administration, in schools, and in the judiciary system. Germans were most hated by the Poles in the years leading up to the war.[5]

Political Options before the War and War Preparations↑

Many Poles met the growing antagonism between the powers that had partitioned Poland at the end of the 18th century with satisfaction. War between these powers seemed to be the only way for the Poles to improve their situation and regain independence. In the final years prior to the outbreak of the war, Polish public opinion was divided into two political camps: one party was pro-Russian, the other pro-Austrian. Roman Dmowski (1864-1939), the pro-Russian camp’s most famous advocate, was one of the leaders as well as the main ideologist of the National Democracy party. Dmowski predicted that the approaching military conflict would have a racial character and would be fought between Teutonic Germany and Slavic Russia. In the future war, Poles should sympathize with and actively help Russia, who, after the victory, would unite all ethnic Polish territories and grant them autonomy within the Russian Empire.[6]

In contrast, pro-Austrian circles argued that the Habsburg Monarchy offered the best conditions for Poles. Following the crushing of a national movement and social revolution in Russian-Poland in 1907, socialist activists who wanted to continue their fight for an independent state moved to Austrian-Poland. There they found a safe haven under the protection of the Austro-Hungarian military in return for promising both to instigate a new anti-Russian uprising in the event of an Austrian-Russian war and to deliver information regarding the location and strength of Russian troops in the borderlands and its military infrastructure to Austro-Hungarian intelligence. In addition, pro-independence activists were granted permission to plan a plot against Russia on Austrian soil.

In June 1908, Polish radicals connected to the military branch of the Polish Socialist Party established the Union of Active Fight (Związek Walki Czynnej, ZWC). The Austrian government discreetly tolerated this secret military organization. Its main aim was to train military commanders for a new national Polish army, in preparation for the next anti-Russian uprising in Russian-Poland. In practice, the ZWC’s activity concentrated on the paramilitary education of patriotic youths in public organizations such as the Society of Riflemen (Towarzystwo Strzelec) and the Union of Riflemen (Związek Strzelecki).[7]

Events in southeastern Europe generated strong impulses to intensify such activity. In October 1912, influenced by Balkan complications and on the eve of an anticipated war between Russia and Austria-Hungary, a delegation consisting of a handful of Polish political parties established an umbrella organization named The Provisional Commission of Parties Striving for Independence (Tymczasowa Komisja Skonfederowanych Stronnictw Niepodległościowych). Its aim was the coordination of activities to reestablish Polish statehood with support from Austria-Hungary.[8]

The Outbreak of the War↑

The war, which finally erupted in the summer of 1914, surprised Poles as well as other European societies. At this point, Poles displayed loyalty toward their own states – Russia, Austria-Hungary, and Germany – respectively. The Russian authorities noted with astonishment that mobilization in Russian-Poland occurred very smoothly and without any major obstacles, not to mention acts of sabotage or upheaval. The Polish reservists joined the ranks peacefully. People gathered in the streets, embracing the Russian army as their own. In Warsaw, Princess Maria Lubomirska (1873-1934) recorded in her diary that the a long line of troops paraded through the streets, surrounded by enthusastic crowds.[9] This unexpected pro-Russian attitude was coupled with a deep-seated resentment of the Germans among Poles in Russian-Poland, due primarily to the Germanization policy in Prussian-Poland and further exacerbated by atrocities committed by the German army in Kalisz, a city located directly on the German-Russian border, in the early days of the war. The German army bombarded Kalisz and set it on fire after an accidental shooting. The city’s historical center was almost entirely obliterated and several hundred inhabitants lost their lives.[10]

But the greatest enthusiasm for the war among Poles was observed in Galicia, a phenomenon easily explained by the political atmosphere in the pre-war period. The National Democrat activist Jan Zamorski (1874-1948) wrote in his memoir that the war was unusually popular and that some Poles believed the war was being waged because of the Russian-Poland’s ties to Galicia.[11] Despite the negative experiences within Germany and the severe limitations placed on Polish national life in Prussian-Poland, Polish recruits loyally but unenthusiastically filled the ranks of the army units. At the beginning of the war, Poles in Prussian-Poland were passive but loyal. The Polish politicians and clergymen, among them Edward Likowski (1836-1915), the new archbishop of Gniezno-Poznań, appealed for a calm fulfillment of duty to the state.[12] Apart from fear of persecution due to the anti-Polish laws, the main reason for this conciliatory attitude was the widespread conviction that powerful Germany would inevitably win the war. Meanwhile, the only concession made to Poles by the German authorities was the nomination of a new Polish archbishop of Gniezno-Poznań after eight years of vacancy. Moreover, a mobilization order was also published in Polish.

Polish Political and Military Activity during the First Two Years of the War↑

From the very beginning of the war, Polish political circles tried to institutionalize their efforts to improve and strengthen the Poles’ political situation against the belligerents. In mid-August 1914, a majority of the Galician political actors, including conservatives, socialists, and even parts of the National Democrats, united to create the Supreme National Committee (Naczelny Komitet Narodowy, NKN) in Cracow as the central political institution of Poles in Austria-Hungary. This resulted in a so-called Polish-Austrian solution, purportedly to liberate and unite Russian-Poland with Galicia as part of Austria-Hungary-Poland.

In Warsaw, National Democrats and Conservatives from Russian-Poland established the National Polish Committee (Komitet Narodowy Polski) in November 1914. It supported Russian military efforts by sponsoring the so-called Puławski Legion, a small voluntary Polish unit within the Russian army. It also appealed to the Polish subjects of Wilhelm II, German Emperor (1859-1941) and Francis Joseph I for passive resistance and welcoming the approaching Russian army. After the fall of Warsaw in August 1915, the committee moved to Petrograd.

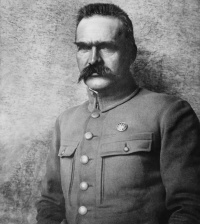

However, in the first stage of the Great War the most active Polish political camp worked in Austria-Hungry. The Polish national activists summoned the First Company under the command of socialist activist Józef Piłsudski (1867-1935) in Cracow and, immediately after the outbreak of hostilities with Russia, crossed the Russian border with the aim of provoking a massive anti-Russian uprising. But they were met with indifference and fear by their compatriots, subjects of the tsar. An anti-Russian uprising, which Piłsudski followers had promised in the pre-war period, turned out to be unrealistic. Only a small group of their fellow Poles were open to cooperation. Nevertheless, in the following months the First Company was gradually transformed into the Polish legions.

Polish voluntary troops were viewed with suspicion by the Austrian military authorities, who were disillusioned by the lack of the promised Polish uprising. But Polish politicians in Galicia successfully convinced the central government in Vienna that these kinds of units could be useful to the monarchy from a political point of view. After acquiescing to the NKN, Piłsudski expanded his legions, which reached approximately 30,000 soldiers by mid-1916, and divided them into three brigades.

This was, however, incomparable to the roughly 3.5 million Polish soldiers who were mobilized to serve in the regular forces of the Russian, Austro-Hungarian, and German armies. Many of them were fighting their compatriots on the battlefields. As recollected by Roman Dybowski (1883-1945), an Austro-Hungarian officer and professor at Jagiellonian University in Cracow, wrote that he once found a wounded officer in the Russian trenches who, upon hearing Polish phrases, cried out: “Please save me. I am a Pole.”[13] For example, in opposite trenches near Łowczówek during Christmas 1914, Polish legionnaires fighting on the Austro-Hungarian side and Polish soldiers from the Russian Siberian Rifles units took turns singing stanzas of Polish Christmas songs. Of the Cracovian bookseller Filipkowski’s twelve nephews, eight served in the Austro-Hungarian army, two in the Russian army, one in the Prussian army, and one in the US Army.[14] From the Polish perspective, the First War could be characterized as a Polish civil war.

Social and Cultural Life↑

From the beginning of the military conflict, Polish society was confronted with all of war’s cruelties. The front lines kept shifting, thus dividing Polish-inhabited territory and causing major disruptions to basic infrastructure. Wojciech Kossak (1857-1942) recalled travelling to Warsaw and seeing only debris and poverty, “tragic masks of feral people who, at the sound of a car engine, looked out for a moment from the ruins of huts, to disappear soon like a spectre.”[15]

During this conflict most of the Polish territories, as well as the territories inhabited by significant Polish minorities, existed under different occupation regimes. For example, in autumn 1914, 80 percent of Galicia was seized by the Russian army and, after the spring and summer offensives of 1915, all of Russian-Poland was occupied by the Central Powers. Only Prussian-Poland was spared from war atrocities on a large scale. As many as 650,000 Galicians are estimated to have fled to the inner provinces of Austria-Hungary to escape the Russian invasion in 1914.[16] During the tsarist army’s retreat from Russian-Poland in summer 1915, several hundred of its inhabitants were forcibly evacuated to the inner provinces of the Romanov Empire.

The occupied land was exploited for the export of food and raw materials and in part as a compulsory labor force. Between 1915 and 1917, approximately 500,000 to 600,000 Poles from Russian-Poland worked in Germany.[17] Because of the lack of raw materials, war destruction or evacuations of machineries (plants), many factories in Russian-Poland were shut down. This resulted in a rise in unemployment. The mood in the Polish territories, both occupied and unoccupied, also deteriorated due to wartime regulations and economic hardships: malnutrition, the black market, high prices, inflation, forced contributions of food from the local population, lack of fuel, and infectious diseases. As the war dragged on, violent social protests, demonstrations, strikes, and riots multiplied. Some of these had an anti-Semitic character (for example, in Cracow in April 1918).[18]

Polish society tried to organize itself to reduce poverty. In major cities, citizen and relief committees were established to organize and coordinate fundraising activities to help wounded soldiers, widows, orphans, and refugees. The Catholic Church and other religious denominations played a large role in the effort. Cracow Archbishop Adam Stefan Sapieha (1867-1951) organized one of the most vital and effective committees with the help of many landowners and university professors. In Switzerland, under the leadership of the Nobel Prize winner for literature Henryk Sienkiewicz (1846-1916), a committee worked to help war victims in Poland, collecting and transferring money to organizations in Polish territories.[19]

Many Polish artists actively brought a cultural angle into the military efforts. Approximately 170 painters, sculptors, and sketchers voluntarily joined the legions, inspired by feelings of living in a time of breakthrough. Their legacy consists of poetry, sculptures, and songs, all expressing Polish soldiers’ war experiences and their hopes of Polish statehood’s resurrection after the war. Between 1915 and 1917, fourteen Polish War Exhibitions were presented in Cracow, Vienna, Warsaw, Zurich, and Bern, among others.[20] To promote the Polish cause on the international level, a Polish Press Bureau was established in Switzerland. It tried to influence media on both sides of the front line.

After 1915, a revival of Polish cultural life occurred in Russian-Poland, now liberated from the tsarist regime. Under the occupation regime, education and judicial systems were polonized.[21]. In autumn 1915, a new academic year began at Warsaw universities, with Polish as the language of instruction.[22] Theaters in major cities such as Warsaw, Cracow, Lviv, and Vilnius presented a national repertoire.[23] But the below-mentioned concessions of the German and Austro-Hungarian occupation authorities in the fields of culture and science were not enough to win the Poles’ hearts and minds. In former Russian-Poland, wartime hardships contributed to a negative picture of the occupants in the Poles’ eyes. They felt misused and exploited rather than treated as an equal and respected ally.[24]

Internationalization of the Polish Question↑

Belligerents tried to win Polish hearts and minds from the very beginning of the war, which as a matter of fact was fought largely on Polish soil on its Eastern Front. On 14 August 1914, the Russian commander in chief, Nikolai Nikolaevich, Grand Duke of Russia (1856-1929), announced that one of the Russian war aims would be to establish a united, autonomous Poland under Romanov scepter, free in its religion, language, and self-government.[25] German and Austro-Hungarian commanders published similar manifestos. They promised to liberate Russian-Poland from the harsh Russian regime’s long-term oppression and to defend Poles, who belonged to the Western civilization, against “barbaric” Asiatic hordes from the East.

The importance of these statements was diminished by the fact that their authors were neither politicians nor monarchs, but military commanders in the field, and that from a political and legal point of view, those promises were not at all binding. Belligerents strived for Polish favor, but at the same time tried to avoid tying their hands with commitments of a political nature. Western allies, such as France and the United Kingdom, kept quiet about the Poles, viewing the Polish question as an internal Russian affair.

A real breakthrough occurred in autumn 1916. After a long discussion within the Central Powers block on the strategy and political aims against Russia, it was finally decided that instead of trying to sign a separatist, compromising peace treaty on favorable conditions, Russia should be “pushed away” from Europe by building a chain of semi-independents “vassal states” between the Baltic and the Black Seas that would maintain close political, economic, and military ties with the Central Powers. Moreover, due to the exhaustion of human, material, and financial resources, Germany under Hindenburg-Ludendorff leadership began implementing a total war concept in summer 1916. This, among other things, included mobilizing all available material for the war effort. They hoped that winning Poles over to the Central Powers’ cause would bring a flood of new Polish recruits.

As part of this new strategy, the so-called “Two Emperors’ Proclamation” was issued on 5 November 1916. In this document, Wilhelm II and Francis Joseph I declared the reestablishment of an independent Polish state in the Russian part of Poland, a constitutional monarchy to be allied with the Central Powers. Poles were then called upon to join the new Polish Army, which would be established on the basis of legions. But when the initial enthusiasm waned, it became apparent that the emperors’ manifesto was too vague. First of all, it was silent regarding the future state’s borders. Second, there was no decision regarding the designation of a future monarch. Despite the lack of more specific political power, the establishment of the Kingdom of Poland on 5 November 1916 would later be seen as an important step in rebuilding Poland.

Nevertheless, despite the aforementioned reservations, the Act of 5 November was a major step forward in reestablishing an independent Poland. Poles were allowed to observe their national celebrations and to establish local government institutions. For the first time since the Vienna Congress in 1815, one of the great powers brought the Polish question onto the international scene. The tsarist government protested in vain. In December 1916, Tsar Nicholas II declared that Poland should be free, united, and possess its own political system, but remain in the union with Russia. In March 1917, following the February Revolution, the Provisional Government acknowledged the Poles’ right to build an independent state, which should maintain its military alliance with Russia. It also allowed for the formation of Polish national units within the ranks of the new republican Russian army. This decision untied French and British hands regarding the Polish case, now no longer considered an internal Russian affair.

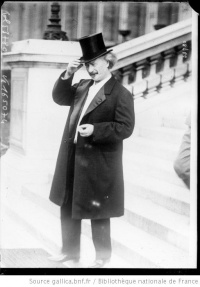

In summer 1917, a group of Polish politicians under Dmowski founded the new Polish National Committee (Polski Komitet Narodowy) in Paris after leaving unstable, revolutionary Russia. This body became a kind of unofficial Polish government in exile and an important Polish partner for Western allies, with whom they consulted about their political ideas concerning East Central Europe. Composer and pianist Ignacy Paderewski (1860-1941) was another one of the prominent activists. Under the committee’s auspices, a new Polish army was formed in France in mid-1917. Their ranks consisted mainly of volunteers from Polish immigrant communities in different countries and German POWs of Polish nationality.

Point thirteen from Woodrow Wilson’s (1856-1924) congressional speech on 8 January 1918 assumed that as a result of the war, an independent Poland, consisting of all ethnic Polish territories and having access to the sea, would be reestablished. This assumption was repeated on 3 June 1918 in the Versailles Declaration during one of the Allied conferences as well as in many unilateral statements of Western allies. In the final two years of the war, Polish sympathies had shifted in favor of the Entente, which promised better conditions to the Poles than the Central Powers.[26]

The Failure of the Pro-Central Powers' Option↑

In mid-January 1917 in occupied Warsaw, a provisional government, the Temporary Council of State (Tymczasowa Rada Stanu, TRS), was established. The German and Austro-Hungarian governors in occupied Russian-Poland appointed its fifteen members. In September 1917, the occupiers nominated the three members of the Regency Council (Rada Regencyjna) as well. These three institutions played an advisory rather than a decisive role. The occupiers were not willing to give the newly established Kingdom of Poland and its institutions real independence and, until the last months of the war, they possessed decisive control over the strategic administrative branches. This led to frustration among Polish society, which demanded real concessions and fulfillment of the Act of 5 November.[27]

Obstructions and delays in executing the Act of 5 November deepened resentment against the Central Powers. Germany and Austria-Hungary postponed important decisions on Polish issues. They could not agree on the future status of occupied Polish territories and secretly competed with each other for the Poles’ sympathies. In April 1917, after arduous talks and much procrastination, Austria-Hungary finally handed over control of three legion brigades to the German governor in Warsaw. They would constitute the core of a massive future Polish national army, which would fight on the Central Powers’ side. These expectations were met with resistance from Piłsudski, who was not prepared to deliver Polish cannon fodder to the Central Powers without real concessions in the process of building an independent Poland.

This dispute ended in summer 1917 in a climax known as “the oath crisis.” Piłsudski and, following his example, the majority of legion soldiers, refused to swear a new oath of fidelity to Wilhelm II as the supreme commander during the war. Former legionaries who were Austrian subjects were forcibly enlisted in the Habsburg army and sent mainly to the Italian front. The former Russian subjects were interned in camps, where many of them stayed until the end of the war. Piłsudski and his closest co-worker, Kazimierz Sosnkowski (1885-1969), were also arrested and interned in Magdeburg’s prison. Only the 2nd Brigade, under Józef Haller (1873-1960), decided to swear a new oath. It was then attached to the Austro-Hungarian army as the Polish Auxiliary Corps (Polnische Hilfskorps) and subsequently sent to the front in Bukowina.[28] The helpless TRS resigned in a vain protest. In the end, approximately 5,000 Polish soldiers and the Polish Military Force (Polnische Wehrmacht) remained under German control.

Even in Galicia, pro-Austrian conservatives lost ground and influence in society to more radical parties such as the National Democratic Party and the Socialist Party. In May 1917, on the eve of a new session of the Austrian parliament, the Polish Deputies Club publicly declared that the main war aim of the Polish nation would be to regain independent status and the unification of all Polish territories, including those with free access to the sea, belonging to Germany. According to a special envoy in occupied Poland, Polish politicians from Austria did not pay attention to the Danube Monarchy’s internal problems, devoting themselves completely to the creation of an independent Poland and seeing Galicia as a part of this political project.[29]

The Final Months of the War↑

From the Polish perspective, the Brest Litovsk Peace Agreement between the Central Powers and the Ukrainian People's Republic, which stipulated that the Chełm Land be transferred to the new Ukrainian state, appeared as open betrayal. Not surprisingly, it was followed by a wave of turbulent protests and street riots. On 18 February 1918, a general strike was declared in Austrian-Poland, leaving the province in a state of near paralysis. The Polish parliamentary club in Vienna publicly declared that it would now stand in opposition to the government. In Galicia, Austrian state symbols were removed from public offices and destroyed. Control was finally restored after reinforcements arrived, but the Central Powers’ image was gravely damaged in the Poles’ eyes.

In the Kingdom of Poland, the government resigned and the Regency Council temporarily broke all relations with the occupation authorities, thereby protesting against the transfer of the Chełm Land to the Ukrainian People’s Republic. The Polish Auxiliary Corps soldiers made the most dramatic decision. Amazingly enough, after a turbulent discussion, it was decided that this unit would join the Polish units that had been formed in territories controlled by Russia, which had sunk into chaos since spring 1917.

After the Brest Litovsk Peace Agreement incident, anti-German and pro-Entente sentiments developed in the Polish territories. Given the assumption that the Entente Powers’ material superiority was too substantial to be overcome, the expectation of a final breakdown of Germany blossomed. Existing pro-Austrian circles were marginalized and played no crucial role in Polish society, which had become more radical. Instead, the National Democratic Party, the Socialist Party, and various peasant parties gained more and more followers. They demanded independence and republican and social reforms. Traditional leaders were forced to step aside for new ones.

Poles openly demanded Piłsudski’s freedom from prison. Paradoxically, for political reasons, his imprisonment had helped him in many ways. Germans did not want to free him unless he agreed to abandon his anti-German policy. This he refused to do, not wanting to tie his hands. As a result of his unwillingness to comply with German demands, his image, that of “rehabilitation,” improved in the eyes of Western allies, who, up until mid-1917, had regarded him as an adherent of the Central Powers. He became an icon of the Polish struggle for independence. For the propertied classes, he was a guarantor that the Russian scenario of a Bolshevik coup would not repeat itself in Poland. This compulsory isolation helped him to create an image as a martyr for Poland, a national leader who allegedly stood above all political quarrels and divisions, and a symbol of the Polish struggle for independence.[30]

In Galicia, respect toward Austrian authorities steadily declined. In summer and early autumn of 1918, demoralized and helpless Austrian authorities in Galicia fell into a state of inertia, their decisions generally ignored by the Polish populace. In many parts of Galicia, inhabitants were terrorized by bands of deserters, hidden in forest complexes. Authorities did not have enough power or energy to fight them off and thus they were forced to tolerate them.[31]

Moreover, Poles accused authorities of plotting with Ukrainians with the aim of dividing Galicia into two provinces, one Polish-dominated, with Cracow as its capital, and the other, Ukrainian, with Lviv as its capital. Poles believed that the military units of primarily Ukrainian soldiers, which were gradually deployed to the eastern parts of Galicia, would pave the way for the division of the province and that this action would set up the conditions for Ukrainians to grasp real power. The Polish public awaited the state’s collapse, which would present an opportunity to seize real power. News of German victories during the spring offensive of 1918 was met with skepticism.

The Building of Independent Poland↑

News of the lost war, the retreat of the German army on the Western Front, the collapse of Bulgaria and Turkey, and the beginning of German-American diplomatic negotiations concerning the conditions of a ceasefire activated Polish political life. Already on 7 October 1918, without prior consultation with the German governor Hans von Beseler (1850-1921), the Regency Council declared the reestablishment of an independent Poland, consisting of all Polish ethnic and historical territories with access to the sea. This was, of course, only a symbolic decision, as Germans still controlled the situation in Warsaw with their governor and garrison. On 23 October 1918, the Regency Council declared the establishment of a new Polish central government under National Democrat Józef Świeżyński (1868-1948). But the greater part of Polish society did not accept this right-wing elite and awaited Piłsudski’s return. Finally, on 10 November 1918, Piłsudski came to Warsaw. The Regency Council handed over its competences to him and dissolved itself. He became head of state (Naczelnik Państwa) with all military and civil power now concentrated in his hands. Under his auspices, a new central, leftist government was appointed with Jędrzej Moraczewski (1870-1944) as prime minster.[32]

With the formal emergence of a new state, chaos took over and the risk of social upheavals like those in Russia emerged. Spontaneously, in different parts of Poland, local power centers arose, which tried to fill the power vacuum, often behaving as independent rulers.

In the former Austrian territories, the Polish Liquidation Commission (Polska Komisja Likwidacyjna) was established in Cracow, as was the Polish National Council (Polska Rada Narodowa) in Cieszyn. Self-appointed local committees searched the military railway transport looking for food and other rare materials that were not allowed to be exported outside Galicia.

Finally, on 30 October 1918, Poles took control of power in Cracow. The last Austrian commander of the city relinquished power. The Austrian garrison was disarmed without opposition and Polish soldiers began sentry duty in the City Hall. In two days, all of Western Galicia was under Polish control and the Austrian authority finally collapsed. On the streets of Western Galicia’s towns, people welcomed the new situation. Jędrzej Moraczewski described the Poles’ reaction to the fact that they had finally achieved their independence as one of overwhelming joy and incredulity.[33] Bows and armbands in the Polish national colors were added to the Austrian uniforms. All symbols of the old regime, such as state emblems, flags, and the double-head stone eagles (maliciously nicknamed “bats”), were spontaneously and quickly removed from the public buildings. At the same time, war began with the Ukraine over the control of eastern Galician territories.[34]

Streams of returning soldiers flooded the Polish territories, rushing to get to their homes. German and Austro-Hungarian soldiers from occupied territories in the former Russian Empire returned home. In Galicia, Polish regiments came from the Italian front and Ukraine to reunite with their families as soon as possible. Polish activists in Germany had remained relatively passive concerning Prussian-Poland during the first two years of the war. Polish deputies, pointing out the loyal fulfillment by Polish soldiers in German uniforms of their duties as subjects of Wilhelm II, demanded the equal treatment of Polish citizens and the abolishment of anti-Polish laws, which were in force in the eastern provinces of Prussia with the aim of fostering Germanization among the Polish population. But not all Poles were supportive. For example, unlike German financial institutions, Polish financial institutions were unwilling to purchase war bonds to finance the war.

Not until 1916 did Polish politicians in Germany secretly establish the Interparty Committee (Komitet Międzypartyjny) as a discussion forum. More activity could be found on the local level, such as participation in national meetings to honor Polish national festivals and gestures of solidarity with Russian and Austrian Poles. During the last months of the war voices spread, demanding, at the very least, national autonomy for Polish territories in Prussia. In October 1918, Polish deputies officially demanded the incorporation of historical and ethnic territories into the newly emerging Polish state, on the basis of Woodrow Wilson’s peace program. In early November, the Supreme People’s Council (Naczelna Rada Ludowa), consisting of Polish deputies and delegates of different Polish social organizations, was established in Poznań. Local national councils then began work in many towns in Great Poland and Pomerania.

In contrast to the situation in Galicia and in spite of losing the war, the political crisis, and revolutionary upheavals in Germany, German administration in Prussian-Poland stood firm, fulfilled its duties, and maintained formal control. German officials did not consider voluntarily resigning from these terrains in favor of a Polish state, especially because these territories were mixed in population. Germans troops, which came back from the former Russian Empire in November 1918, still regarded the 1914 border as valid. In December 1918, the provincial parliament of the Great Poland region was summoned to Poznań to decide the region’s political future. At the end of the month, as a result of Ignacy Paderewski’s arrival, an anti-German uprising erupted in Great Poland. Poles controlled the greatest part of the region until the ceasefire in February 1919.[35]

A Real End of the War↑

The early months of formal independence were both dramatic and dynamic. The new central authorities in Warsaw first had to gain real control over vast territories with different local political centers and form an effective, united national army. The new central Polish government had to keep public order, a task made difficult by factors such as hunger, poverty, the approaching winter, Spanish flu, a wave of spontaneous demobilization and mass migration, Bolshevik propaganda, and anti-Semitic resentment and violence (especially in Galicia). This turned out to be an extremely difficult task. Politicians also quarreled over the shape of the future constitutional system.

A parliamentary election in January 1919 provided legitimacy to the new political elite. The Polish state was active on the international level as well. At the Paris Peace Congress, the new Prime Minister and Minister of Finance, Ignacy Paderewski, and the leader of the National Committee in Paris, Roman Dmowski, represented Poland. Both leaders were supported by a large contingent of experts. To strengthen the Polish negotiating position, a special public relations campaign in the Western media was waged, which included the establishment of support committees. British delegates in particular tried to restrain the Warsaw government’s territorial appetite. After a few months of debate, the powers decided to cede regions of Great Poland and Pomerania, but without Danzig (Gdańsk), to Poland. The fate of the contentious, nationally mixed regions of Upper Silesia and Masuria would be decided by plebiscites, organized under the auspices of Western allies. The Polish eastern border would be drawn on the battlefields. Poland ratified the Treaty of Versailles in September 1919.[36]

As part of the overall post-war agreement with the Western allies, Poland and other East-Central European countries were obliged to sign the so-called “Little Treaty of Versailles,” which guaranteed the rights of national minorities, including Jews. During the war, the Jewish population on what would be Polish territory after 1921 was divided between loyalty toward the existing states, the Polish national cause, and Zionist and socialist ideologies. However, the majority of Jews were not interested in politics at all, merely trying to survive, struggling to find enough food and fuel for heating, and fearing the growing anti-Semitic mood.[37]

It must be emphasized that military operations did not end on Polish soil in November 1918, but rather were followed by a border struggle in the new state, which continued for the next three years. Fighting took place in many areas: Eastern Galicia (war with the Ukrainians, October 1918 to July 1919), Great Poland (anti-German uprising, December 1918 to February 1919), Upper Silesia (three anti-German uprisings, 1919-1921), the raid on the Vilnius region (October 1920), and the war with Soviet Russia (until March 1921). From the Polish perspective, the First World War should be treated together with the above mentioned border struggles, which did not end until the signing of the Polish-Soviet Peace Treaty in Riga on 18 March 1921.[38] In the following years Poland remained isolated in the region and relations with the majority of its neighbors, with the exception of Romania and Latvia, remained cool or absolutely frozen, full of either suspicion and distrust or only lightly concealed hostility.

Conclusion↑

At the beginning of the First World War, no Pole could have even imagined that the war would take a course so favorable to the Poles. As a result of this conflict, the three powers that had partitioned Poland at the end of the 18th century collapsed, broke up, and ceased to exist. This paved the way for a fully independent and united Poland. In the summer of 1914, one could only dream of an autonomous and united Poland within Russia or Austria-Hungary. The victorious powers, however, wrote on their standards such postulates as republicanism and democracy, regarded national self-determination and sovereignty as fundamental to a new post-war order. In the last two years of the conflict, Poles broke most of the binds connecting them to the Central Powers and came to the victorious coalition as a partner. On the other hand, the war turned out to be very destructive for Poles and their land.

Piotr Szlanta, University of Warsaw

Section Editors: Ruth Leiserowitz; Theodore Weeks

Notes

- ↑ Holzer, Jerzy/Molenda, Jan: Polska w pierwszej wojnie światowej [Poland in the First World War], Warsaw 1973; Pajewski, Janusz: Odbudowa państwa polskiego 1914-1918 [The reconstruction of the Polish State 1914-1918], Poznań 2005.

- ↑ Zieliński, Konrad: Stosunki polsko-żydowskie na ziemiach Królestwa Polskiego w czasie pierwszej wojny światowej [Polish-Jewish relations in the lands of the Polish Kingdom during the First World War], Lublin 2005; Grynberg, Daniel/Snopko, Jan/Zackiewicz, Grzegorz (eds.): Lata Wielkiej Wojny. Dojrzewanie do niepodległości 1914-1918 [Years of the Gerat War. Maturation of independence], Białystok 2007.

- ↑ Weeks, Theodore R.: Nation and State in Late Imperial Russia. Nationalism and Russification on the Western Frontier 1863-1914, DeKalb 1996.

- ↑ Binder, Harald: Galizien in Wien. Parteien, Wahlen, Fraktion und Abgeordnete im Übergang zur Massenpolitik, Vienna 2005.

- ↑ Chwalba, Andrzej: Historia Polski 1795-1918 [History of Poland 1795-1918], Cracow 2000, pp. 319-531; Zdrada, Jerzy: Historia Polski 1795-1914 [History of Poland 1795-1914], Warsaw 2005, pp. 524ff.

- ↑ Świętek, Ryszard: Lodowa ściana. Sekrety polityki Józefa Piłsudskiego 1904-1918 [A wall of ice. Secrets of Józef Piłsudski’s policy 1904-1918], Cracow 1998; Gaul, Jerzy: Działalność informacyjno-wywiadowcza polskich organizacji niepodległościowych w latach 1914-1918 [Intelligence activity of Polish pro-independency organisations in years 1914-1918], Warsaw 2001; Bachmann, Klaus: Ein Herd der Feindschaft gegen Rußland. Galizien als Krisenherd in den Beziehungen der Donaumonarchie mit Rußland 1907-1914, Vienna 2001.

- ↑ Wrzosek, Mieczysław: Polski czyn zbrojny podczas pierwszej wojny światowej 1914-1918 [The Polish military contribution during the World War, 1914-1918], Warsaw 1990, pp. 21-51; Potkański, Waldemar: Ruch narodowo-niepodległościowy w Galicji przed 1914 rokiem [National-democratic movement in Galicia prior to 1914], Warsaw 2002; Garlicki, Andrzej: U źródeł obozu belwederskiego [The genesis of Belvedere party], Warsaw 1978, pp. 200-239.

- ↑ Pajewski, Janusz: Odbudowa państwa polskiego 1914-1918 [Rebuilding the Polish state 1914-1918], Poznań 2005, pp. 21-45; Wrzosek, Polski 1990, pp. 13-51.

- ↑ Quoted in: Pajewski, Janusz (ed.): Pamiętnik księżnej Marii Lubomirskiej 1914-1918 [Memoirs of Princess Maria Lubomirska], Poznań 1997, p. 15: “Wieczorem szły pod naszymi oknami liczne oddziały wojska, długim korowodem. Towarzyszył im tłum entuzjastyczny, krzyczący hurra!!! Niech żyje armia! Cała ulica drżała zapałem.” - “In the evening a long column of troops went by our windows. It was accompanied by an enthusiastic crowd shouting: ‘Hurrah!!! Long live the army!’ The whole street was shaken by ardor.” [translated by author]

- ↑ Woźniak, Mieczysław-Arkadiusz: Kalisz. Pogrom miasta 1914 [Kalisz. Anihliation of the town 1914], Kalisz 1995; Engelstein, Laura: A Belgium of Our Own. The Sack of Russian Kalisz, August 1914, in: Kritika. Explorations in Russian and Euroasian History 10/3 (2009), pp. 441-473.

- ↑ Quoted in: Wątor, Adam: Narodowa Demokracja w Galicji do 1918 roku [National Democracy in Galicia until 1918], Szczecin 2002, pp. 303f.: Sama wojna jest nadzwyczaj popularna … Nie wiem czy jest kilka tuzinów Polaków, którzy by te wojnę brali za co innego, jak za wojnę o przyłączenie Królestwa do Galicji, czyli o wskrzeszenie Polski.” - “The war is unusually popular...I doubt, if there are a few dozens of Poles, who would not regard this war as conducted for the sake of the affiliation of Russian-Poland to Galicia.” [translated by author]

- ↑ Watson, Alex: Fighting for Another Fatherland. The Polish Minority in the German Army, 1914-1918, in: English Historical Review, 126/522 (2011), pp. 1137-1166.

- ↑ Quoted in: Dybowski, Roman: Siedem lat w Rosji i na Syberii [Seven years in Russia and Siberia], Warsaw 2009, p. 39: “Gdyśmy się wdarli wreszcie do okopów ... zastałem tam oficera rosyjskiego leżącego obok karabinu maszynowego, z którego całe rano pluł na nas kulami. Już się do oficera dobierali nasi sanitariusze, zaczynając, jak zwykle, od zegarka, nie od rany. Ranny słyszy wokół siebie różne “Rany boskie!” i “Psia mać!” naszych wiarusów, widzi u mnie oficerskie odznaki i woła: “Niech mnie pan poratuje! Jestem Polak!”. - “When we finally seized the Russian trenches...I found a Russian officer there, lying near a machine gun, from which we were under fire the whole morning. As usual, our paramedics attended to him first by taking his wristwatch instead of dressing his wound. The wounded man hearing around himself Polish expressions, such as “Rany Boskie” and “Psia mać!”, and seeing officer distinctions on my uniform, asked me: Please save me. I am a Pole.” [translated by author]

- ↑ Sobieski ,Wacław: Dzieje Polski [A History of Poland], Warsaw 1938, vol. 3, p. 139; Kukiel, Marian: Dzieje porozbiorowe Polski (1795-1921) [A history of Poland during the partition time 1795-1921], London 1993, p. 561.

- ↑ Quoted in: Kossak, Wojciech: Wspomnienia, Warsaw 1971, p. 298. “Jechałem więc […] do Warszawy, jechałem przez tę krainę gruzów i nędzy. Widziałem tragiczne maski zdziczałych ludzi, z przerażeniem na odgłos motoru z ruin chałup przez mgnienie oka wyglądające, ginące wnet jak upiory; widziałem po lasach wychudzone kobiety, zobojętniałe nawet na ludzkie wołanie, szukające czegoś wśród leśnego igliwia.” - “I travelled to […] Warsaw, I travelled through this land of debris and poverty. I saw tragic masks of feral people who, at the sound of a car engine, looked out for a moment from the ruins of huts, to disappear soon like a spectre. I saw in forests, emaciated women, indifferent even to the human call, who were looking for something in the undergrowth.” [translated by author]

- ↑ Hagen, Mark von: War in a European Borderland. Occupations and Occupation Plans in Galicia and Ukraine 1914-1918, Washington 2007, pp. 23-28; Holquist, Peter: The Role of Personality in the First (1914-1915) Russian Occupation of Galicia and Bukovina, in: Dekel-Chen, Jonathan et al. (eds.): Anti-Jewish violence. Rethinking the Pogrom in East European History, Bloomington 2012, pp. 52-74.

- ↑ Westerhoff, Christian: Zwangsarbeit im Ersten Weltkrieg. Deutsche Arbeitskräftepolitik im besetzten Polen und Litauen 1914-1918, Paderborn 2012.

- ↑ Holzer/Molenda, Polska 1973, pp. 151-171; Lehnstaedt, Stephan: Das Militärgouvernement Lublin. Die “Nutzbarmachung” Polens durch Österreich-Ungarn im Ersten Weltkrieg, in: Zeitschrift für Ostmitteleuropa-Forschung 1/1 (2012), pp. 1-26; Polsakiewicz, Marta: Spezifika deutscher Besatzung in Warschau, in: Zeitschrift für Ostmitteleuropa-Forschung 58/4 (2009), pp. 501-537.

- ↑ Płygawko, Danuta: Sienkiewicz w Szwajcarii. Z dziejów akcji ratunkowej dla Polski w czasie pierwszej wojny światowej [Sienkiecz in Switzerland. Accounts from the history of the relief action for Poland during the First World War], Poznań 1986.

- ↑ Wyganowska, Wanda: Sztuka legionów Polskich 1914-1918 [The Art of the Polish Legions 1914-1918], Warsaw 1994; Milewska, Wacława/Zientara, Maria: Sztuka Legionów Polskich i jej twórcy 1914-1918 [The Art and the artists of the Polish Legions 1914-1918], Cracow 1999.

- ↑ Kauffman, Jesse: Schools, State-Building and National Conflict in German Occupied Poland 1915-1918, in: Keene, Jennifer D./Neiberg, Michael S. (eds.): Finding Common Ground. New Directions in the First War Studies, Leiden/Boston 2011, pp. 113-137.

- ↑ Stempin, Arkadiusz: Die Wiedererrichtung einer polnischen Universität: Warschau unter deutscher Besatzung, in: Maurer, Trude (ed.): Kollegen - Kommilitonen- Kämpfer. Europäische Universitäten im Ersten Weltkrieg, Stuttgart 2006, pp. 127-145.

- ↑ Sivert, Tadeusz/Taborski, Roman: Teatr polski w latach 1890-1918. Zbór rosyjski [Polish Theater 1890-1918 in the Russian part of Poland], Warsaw 1988, pp. 732-745.

- ↑ Spät, Robert: Für eine gemeinsame deutsch-polnische Zukunft? Hans Hartwig von Beseler als Generalgouverneur in Polen 1915-1918, in: Zeitschrift für Ostmitteleuropa-Forschung 58/4 (2009), pp. 469-500.

- ↑ Achmatowicz, Aleksander: Polityka Rosji w kwestii polskiej w pierwszym roku Wielkiej Wojny 1914-1915 [Russia's Policy in the Polish question in the first year of the Great War 1914-1915], Warsaw 2003, pp. 191-209.

- ↑ Zamoyski, Jan: Powrót na mapę. Polski Komitet Narodowy w Paryżu 1914-1919 [Re-appearance on the map. Polish National Committee in Paris 1914-1919], Warsaw 1991.

- ↑ Pajewski, Odbudowa 2005, pp. 127-152; Holzer/Molenda, Polska 1973, pp. 244ff; Szymczak, Damian: Między Habsburgami a Hohenzollernami. Rywalizacja niemiecko-austro-węgierska w okresie I wojny światowej a odbudowa państwa polskiego [Between Habsburg and Hohenzollern. The German and Austro-Hungarian rivalry during WW1 and the making of the Polish state], Cracow 2009, pp. 177-235.

- ↑ Snopko, Jan: Finał epopei Legionów Polskich 1916-1918 [The Finale of the Polish Legions Epos], Białystok 2008, pp. 129-317.

- ↑ Mroczka, Ludwik: Galicji rozstanie z Austrią. Zarys monograficzny [The parting of Galicia from Austria. An outline], Cracow 1990, pp. 20f.

- ↑ Suleja, Włodzimierz: Józef Piłsudski, Wrocław 1995, pp. 139-172.

- ↑ Plaschka, Richard/Haselsteiner, Horst/Suppan, Arnold: Innere Front. Militärassistenz, Widerstand und Umsturz in der Donaumonarchie 1918, Munich 1974, vol. 1, pp. 299-315, vol. 2, pp. 89-94.

- ↑ Kukiel, Dzieje 1993, pp. 573-593.

- ↑ Quoted in: Przewrót w Polsce, cz.1, Rządy ludowe. Szkic wypadków czasów wyzwolenia Polski do 16 stycznia 1919 roku. Napisał poseł E. K. [A coup in Poland, part 1, A rule of peasant party. An outline of occurrences from the liberation of Poland until 19 January 1919 . Written by deputy E.K.], Warsaw–Cracow 1919, p. 17. “Nie sposób oddać tego upojenia, tego szału radości, jaki ludność polską w tym momencie ogarnął. Po 120 latach prysły kordony! Nie ma ‘ich!’ Wolność! Niepodległość!” - “One could not describe this rapture, this ecstasy of joy, which in this moment swept through the Polish populaces. Borders vanished after 120 years! There is no more ‘they’! Freedom! Independence!’” [translated by author]

- ↑ Klimecki, Michał: Das Ende der österreichischen Souveränität in Galizien im Oktober - November 1918, in: Rzepniewski, Andrzej (ed.): Zwischen Wien und Lemberg. Die Vorträge der polnisch-österreichischen Tagung zum 80. Jahrestag des Ausbruchs des Ersten Weltkrieges, Warschau den 17. November 1994, Warsaw 1996, pp. 163-170; Śliwa, Michał: Pierwsze ośrodki władzy polskiej w Galicji w 1918 r. [First centers of the Polish authority in Galicia in 1918], in: Dzieje Najnowsze 4 (1988), pp. 63-78.

- ↑ Trzeciakowski, Lech: Pod pruskim zaborem 1850-1918 [Under Prussian Rule], Warsaw 1973, pp. 338-361; Grot, Zdzisław: Antoni Czubiński, Powstanie wielkopolskie 1918-1919 [Uprising in the Greater Poland Region], Poznań 2006.

- ↑ Ajnenkiel, Andrzej: Od rządów ludowych do przewrotu majowego. Zarys dziejów politycznych Polski 1918-1926 [The period between the rule of the peasant party and the May coup in Poland. An outline of political history of Poland 1918-1926], Warsaw 1964, pp. 86-98; Wyszczelski, Lech: O Polsce w Wersalu [About Poland in Versailles], Toruń 2008.

- ↑ Zieliński, Stosunki 2005; Gałęziowski, Marek: Na wzór Berka Joselewicza. Żołnierze i oficerowie pochodzenia żydowskiego w Legionach Polskich [For example Joselewicz. Soldiers and officers of Jewish origin in the Polish Legions], Warsaw 2010; Rozenblit, Marsha L.: Reconstructing a National Identity. The News of Habsburg Austria During World War, Oxford 2001.

- ↑ Brzoza, Czesław/Sowa, Andrzej Leon: Historia Polski 1918-1945, Cracow 2007, pp. 26-49; Czubiński, Antoni: Walka o granice wschodnie Polski w latach 1918-1921 [Struggle for the eastern borders of Poland 1918-1921], Opole 1992.

Selected Bibliography

- Borodziej, Wlodzimierz: Geschichte Polens im 20. Jahrhundert, Munich 2010: Beck.

- Davies, Norman: God's playground. A history of Poland in two volumes. 1795 to the present, volume 2, Oxford 1982: Clarendon Press.

- Garlicki, Andrzej: U zródel obozu belwederskiego (The genesis of the Belvedere party), Warsaw 1978: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe.

- Gerson, Louis L.: Woodrow Wilson and the rebirth of Poland 1914-1920. A study in the influence an American policy of minority groups of foreign origin, Hamden 1972: Archon Books.

- Holzer, Jerzy / Molenda, Jan: Polska w pierwszej wojnie światowej (Poland during the First World War), Warsaw 1973: Wiedza Powszechna.

- Mikietynski, Piotr: Niemiecka droga ku Mitteleuropie. Polityka II Rzeszy wobec Królestwa Polskiego, 1914-1916 (The German way to Mitteleuropa. The politics of the Second Reich and the Kingdom of Poland, 1914-1916), Krakow 2009: Towarzystwo Wydawnicze Historia Iagellonica.

- Milewska, Wacława / Nowak, Janusz Tadeusz / Zientara, Maria: Legiony Polskie 1914-1918. Zarys historii militarnej i politycznej (The Polish legions 1914-1918. A short military and political history), Kraków 1998: Księg. Akademicka.

- Pajewski, Janusz: Odbudowa panstwa polskiego, 1914-1918 (Rebuilding the Polish state, 1914-1918), Warsaw 1978: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe.

- Sukiennicki, Wiktor / Siekierski, Maciej: East Central Europe during World War I. From foreign domination to national independence, Boulder; New York 1984: East European Monographs; Columbia University Press.

- Szymczak, Damian: Między Habsburgami a Hohenzollernami. Rywalizacja niemiecko-austro-węgierska w okresie I wojny światowej a odbudowa państwa polskiego (Between Habsburgs and Hohenzollerns. The German-Austro-Hungarian rivalry in the period of World War I and the construction of the Polish state), Krakow 2009: Wydawnictwo Avalon.

- Wandycz, Piotr Stefan: The lands of partitioned Poland, 1795-1918, Seattle 1974: University of Washington Press.

- Westerhoff, Christian: Zwangsarbeit im Ersten Weltkrieg. Deutsche Arbeitskräftepolitik im besetzten Polen und Litauen 1914-1918, Paderborn 2012: Schöningh.

- Wrzosek, Mieczysław: Polski czyn zbrojny podczas pierwszej wojny światowej, 1914-1918 (The Polish military contribution during the World War, 1914-1918), Warsaw 1990: Wiedza Powszechna.