Before the War↑

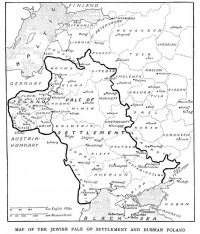

Zionism was born in the fin-de-siècle, and the movement’s discourse owed as much to the language and ideas of that period as they did to the growing anti-Semitism in Europe. The murderous pogroms in the eastern part of the continent, as well as the establishment of ethnic nationalism and a biological discourse, had devastating effects on the ability and desire of Jews to assimilate in Western societies. Some Jews came to believe that a solution to the “Jewish Problem” could only be achieved through the creation of a Jewish national sovereign identity.

Despite this basic unity of purpose, Zionism was not a monolithic ideology. Factions differed on substantial issues like the rate and implementation of the immigration to Palestine, or even on whether the “Holy Land” should be the site upon which to fulfill the movement’s goals. Cultural Zionism, for example, understood the “Land of Israel” as the irreplaceable spiritual center of Jewish life and Hebrew culture, while Theodor Herzl (1860-1904) and political Zionism focused on securing imperial approval for a territorial grant to the Jewish people.

Nevertheless, perhaps the most influential type of Zionism (at least in retrospect) was labor Zionism and the coalescence of the principal Zionist ethos of the Halutz (pioneer), which emphasized the cultivation of the Land of Israel as the source for Jewish redemption from the hardship of the diaspora. The idea of creating a strong and vital “new Jew,” the antithesis of the stereotypically weak and degenerate Jew of the diaspora, is a testament to the fact that Zionism was – perhaps above all else – a modern revolution of Jewish life, an attempt to create a “new Jewish subject” in control of its own destiny.

The pre-war era was key to the movement’s development, witnessing early waves of Jewish immigration into Palestine, the foundation of the World Zionist Organization (and its first Congress, held in Basel in 1897), and the establishment of Tel Aviv, the first Hebrew city, as well as the first secular Jewish settlements and neighborhoods in Palestine (Yishuv). Modern Hebrew culture was in its infancy at the time, and the groundwork was laid not only for Zionist political organizations in Europe and Palestine, but also for the Hebrew public sphere (newspapers, education, etc.) in the Yishuv.

Nevertheless, until 1914, Zionism progressed only slowly towards its goal and was far from fulfilment. After the death of Herzl, one of the fathers of Zionism, in 1904, the movement lacked charismatic leadership, and its advocates constituted only a small fraction not just of Palestine’s overall population, but of the global Jewish population as well. Palestine’s existing Jewish community was weak, and almost entirely dependent on foreign and philanthropic donations for survival. Most importantly, Zionism’s nationalist goals were obstructed by the fact that Palestine was not an independent territory, but part of the Ottoman Empire – a state of affairs that had existed for 400 years and that, even in 1914, seemed unlikely to change.

First World War↑

In some respects, Zionism’s difficulties were only exacerbated by the war. The Yishuv suffered from shortages of food and medical supplies, the donations stopped, and Tel Aviv was evacuated by the Ottomans. Furthermore, the regime revoked its pre-war exemptions for foreign citizens (capitulations), so Jews who had immigrated to Palestine from Russia, an enemy state, had to choose between leaving the Yishuv or accepting Ottoman rule, paying taxes, and even joining the army. In the four years of the war, the Yishuv lost around 35 percent of its residents, dropping from around 85,000 people to a mere 55,000. Jews fought in the war on both sides of the conflict, withdrawing from any unifying national Zionist agenda in favor of representing their various homelands on the battlefield.

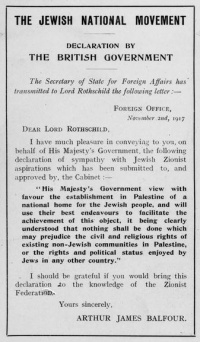

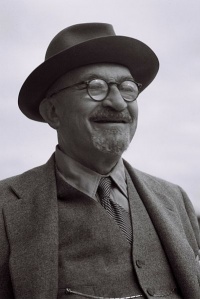

In other ways, however, the war was a blessing in disguise for Zionism, largely because Zionism’s primary patronage shifted into British and American hands. The British government’s increased interest in Zionism and Palestine allowed renowned British Zionist leader Chaim Weizmann (1874-1952) to push for the Balfour Declaration in 1917, an official promise from the British government to act in favor of the creation of Jewish national home in Palestine.

After the War↑

In the wake of the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, the conquering of Palestine by the British Empire, and the establishment of the British Mandate, the Yishuv and Hebrew culture grew at an exceptional pace, especially after 1933, when the rise of Nazi Germany prompted massive immigration by the German-Jewish middle class. In 1939, there were close to 500,000 Jewish inhabitants in Palestine, an increase that violently intensified the Jewish community’s conflict with the local Arab population. Nevertheless, Zionists were still a minority, representing 30 percent of Palestine’s residents and only about 3 percent of the world’s Jewish population. During the interwar years, many Jews (and even Zionists) proposed numerous solutions to problems of Jewish life in the diaspora. Those proposals, drawing upon a variety of ideas, such as socialism and human rights, hoped to achieve Jewish autonomy in Europe and not necessarily in Palestine. The desire for Jewish sovereignty would thus ultimately be achieved only in 1948, mainly in response to the unforeseen horrors of World War II and the Holocaust.

Ofer Idels, Tel Aviv University

Reviewed by external referees on behalf of the General Editors

Selected Bibliography

- Chowers, Eyal: The political philosophy of Zionism. Trading Jewish words for a Hebraic land, Cambridge 2012: Cambridge University Press.

- Neumann, Boaz: Land and desire in early Zionism, Waltham 2011: Brandeis University Press.

- Shapira, Anita: Israel. A history, Waltham 2012: Brandeis University Press.

- Shimoni, Gideon: The Zionist ideology, Waltham 1995: Brandeis University Press.

- Stanislawski, Michael: Zionism and the fin de siècle. Cosmopolitanism and nationalism from Nordau to Jabotinsky, Berkeley 2001: University of California Press.