Introduction↑

The hostile relationship of the Russian military, civil authorities and parts of the population on the western periphery of the Russian Empire to the Jews during World War I was well known to contemporaries and was even defined by them as a “war”. Indeed, trying to convince Nicholas II, Emperor of Russia (1868-1918) to modify the anti-Jewish policy of the General Headquarters, Finance Minister Petr L. Bark (1869-1937) told him in the summer of 1915, “we cannot and must not simultaneously wage war against Germany and the Jews. In that case we cannot count on victory.”[1]

The concept of a “national” military doctrine based on citizens’ loyalty and willingness to sacrifice for the sake of the motherland, can be seen to have influenced the Russian army’s aggressive policy toward the Jews. In the years preceding World War I, the army leadership manifested an increasingly negative attitude toward the Jews. Russian generals regarded the Jews as a harmful and dangerous element of the population that was unsuited for military service and would be disloyal in wartime. The army was more anti-Jewish in its orientation than the majority of society. According to the military, the Jews’ lack of military might did not eliminate the potential danger from the Jews, who were feared to directly aid the enemy and exert a demoralizing effect on Russian soldiers. Simplistic logic convinced the military and civil authorities that the Jews ─ a persecuted and oppressed minority ─ could not be Russian patriots and would not want to make sacrifices for the motherland. “Progressive” military thinking in the prewar years propounded an active policy of neutralizing “disloyal elements” of the population as a condition for military success.

The military command’s negative stereotypes of the Jews were formed in the pre-war years. These stereotypes were exasperated by the broad authority granted to the military command in the sphere of civil rule near the front and the unforeseen difficulty of military actions and the Russian army’s resulting failure and defeat. Strong anti-Semitic sentiments shared by a group of high-ranking commanders (including Nikolai N. Yanushkevich (1868-1918), the Chief of Staff of the General Headquarters), added an element of personal hatred to the anti-Jewish measures of the army.

Russian Army Anti-Jewish Measures↑

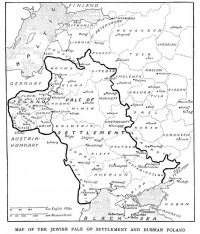

From the first days of the war, Russian commanders pointed to the alleged disloyalty of Russia’s Jewish population, its direct complicity with the enemy, and its involvement in espionage. Utilizing the broad authority entrusted to military authorities by wartime acts, the army began to solve the “problem” of Jewish disloyalty. In this “struggle” the army expelled Jews from various localities, took hostages, and restricted the movement of Jews near the front line. The General Headquarters (Stavka) officially adopted these measures in a published statement in January 1915 that set forth the charges against the Jews. No distinction was made between Jews who were Russian citizens and Jews in occupied Galicia. The proposed measures were either supposed to ensure the Jews’ loyalty by instilling fear of expulsion or execution, or to eliminate the Jews’ “harmfulness” by restricting contacts between the troops and Jews.

As a direct result of this January 1915 declaration, the Russian command made several attempts to carry out a mass deportation of the Jewish population from the front lines (in particular, from Plotsk gubernia in the Kingdom of Poland and from occupied Galicia). These attempts were unsuccessful because the policy of mass deportations required precise coordination between the military and civil authorities both near the front lines (where the governors and police were responsible for implementing deportations) and in the rear, which had to receive the expelled population. The military command was unable to attain such cooperation because of the strong opposition to deportations by civil authorities on various levels. In May 1915, however, about 200,000 Jews were expelled from the provinces of Kovno and Kurland; this mass deportation was carried out by the Commander of the X. Army General Nikolai A. Radkievich (1851–?) with the support of General Yanushkievich from the General Headquarters. The masses of expelled Jews disrupted transport operations and disorganized the army’s rear during the crucial summer months of 1915. This was the sole deportation on such a scale, but for the various ranks of the military command, local expulsions remained a convenient and widely used means of clearing the battle area of the undesirable presence of the Jewish population. From 1914 to 1916 at least 189 Jewish communities in the Russian Empire, Galicia and Bukovina suffered from deportations and expulsions.

Hostage-taking of Jews, a measure that affected the entire Jewish population near the front, was also considered legitimate. As of May 1915, hostage-taking, which was simpler to carry out than expulsions, was supposed to replace the latter as a basic means of assuring the Jews’ loyalty. Both general expulsions and the taking of civilian Jewish hostages became symbols of the military authorities’ repressive policy toward the Jews, which was widely discussed in the country (including at the meetings of the Council of Ministers) and worldwide.

Army Pogroms↑

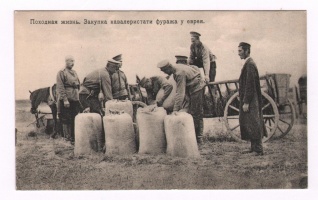

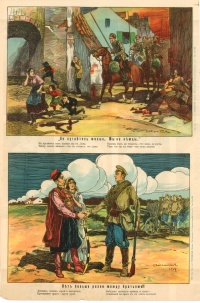

The hostile attitude toward the Jews degenerated into aggressive behavior by the Russian military toward the Jewish population. Army officers and soldiers believed en masse that the Jews were guilty of treason and wrecking. Moreover, the Russian army employed looting and violence in their method of conducting war. Looting, robbery, and violence (including rape) peaked during the “Great Retreat” of the Russian army in the summer and autumn of 1915, while the Cossacks and regular troops received orders to implement a “scorched earth” policy. Robbery and looting of Jewish populations were typical for the whole front line area; pogroms were characteristic of Russian-occupied Galicia from September to November 1914. Pogroms also occurred when the army was forced to retreat, as for example in Lithuania and Byelorussia in the summer and autumn of 1915. The officers and military commanders preferred to ignore the troops’ conduct toward the Jews, and sometimes even joined the looters and perpetrators. The same kind of anti-Jewish violence, carried out by military units and ignored or supported by their commanders, continued and increased during the pogroms of the Russian Civil War (1917–1922).

International Consequences↑

On the international political arena the Jewish question damaged Russia’s prestige and impeded the procurement of credit. During 1915–1916, Western governments and financial backers demanded an easing of the Jews’ condition and a change in the attitude toward them as a condition for extending financial aid to Russia. It is thus very clear that the army’s treatment of the Jews harmed Russia’s international financial position and its ability to wage war effectively.

Semion Goldin, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem

Section Editors: Yulia Khmelevskaya; Katja Bruisch; Olga Nikonova; Oxana Sergeevna Nagornaja

Notes

- ↑ Bark, Petr L.: “Vospominania” [Memories], in: Vozrozhdenie, April 1966, p. 93.

Selected Bibliography

- Anonymous: Iz chernoi knigi russkogo evreistva. Materialy dlia istorii voiny 1914 – 1915 godov (From the black book of the Russian Jewry. Materials for the history of war 1914-1915), in: Evreiskaia starina 10, 1918, pp. 195-296.

- Gessen, I. V. (ed.): Dokumenty o presledovaniach evreev (Documents on persecutions of the Jews), in: Arkhiv russkoi revoliutsii XIX, 1928, pp. 245-284.

- Holquist, Peter: The role of personality in the first (1914-1915) Russian occupation of Galicia and Bukovina, in: Dekel-Chen, Jonathan L. (ed.): Anti-Jewish violence. Rethinking the pogrom in East European history, Bloomington 2010: Indiana University Press, pp. 52-73.

- Lohr, Eric: The Russian Army and the Jews. Mass deportation, hostages, and violence during World War I, in: Russian Review 60/3, 2001, pp. 404-419.

- Löwe, Heinz-Dietrich: The Tsars and the Jews. Reform, reaction, and anti-semitism in imperial Russia, 1772-1917, Chur 1992: Harwood Academic Publishers.

- Sanborn, Joshua A.: The genesis of Russian warlordism. Violence and governance during the First World War and the Civil War, in: Contemporary European History 19/3, 2010, pp. 195-213.