The Martial Estate↑

Definition↑

Russian society in the 18th century is commonly described as a hierarchical system of estates, in which the state categorised the population according to service rendered. The Cossack estate’s duty was universal male military service in mounted formations. In return, the imperial regime granted the Cossacks collective allotments of land and exemption from taxation. Historians such as Gregory Freeze, however, have argued that Russia’s social structure was more dynamic and complex. It comprised manifold groups that emerged in different processes and adapted to the estate order. They were distinguished not just by position in law but by cultural markers. The Cossacks exemplify this complexity.

Composition↑

By 1914 there were eleven separate Cossack communities, known as hosts, or voiska. Each had its own territory, administration, economy, religious preference and traditions. Some, including the Zabaikal, Amur and Ussuri hosts, were created by the regime to guard its long southern border and facilitate expansion into the Far East. The Don, Terek and Ural Cossacks, on the other hand, originated independently through the mingling of Tatar nomads and Slavic frontiersmen living on the steppe grasslands in the 15th century, who made a living as professional soldiers or by raiding surrounding settlements. As these warrior bands coalesced into organised communities, the tsarist state subordinated them through methods varying from oaths of allegiance and legal charters to brutal suppression of revolt.

Cossacks nevertheless retained much of their political structure and culture. Hosts were not subdivided into the counties and villages of the Russian peasantry but into military districts and large settlements called stanitsas. These settlements were governed by assemblies of adult males responsible for allotting land and imposing judicial sentences. They were presided over by an elected leader, the ataman, who also mustered men for military service. Cossacks displayed their democratic and warrior ideals in distinctive song, folklore and dress, for example the baggy, striped trousers, the single forelock of hair and the practice of wearing military uniform when off-duty.

Hosts were not homogenous, however. Despite egalitarian values and institutions and the absence of serfdom, some Cossacks gained repeated election to powerful positions, forging a wealthy elite who assisted the autocracy in subjecting the Cossack population to state control in return for some of the privileges and status of the nobility. Cossacks also had their own clergy, merchants and ethnic minorities. Women dominated the domestic economy when the men were called up and had their own customs.

Modernisation↑

By the end of the 19th century, the system of Cossack military service as well as the living conditions in the hosts were strained. Each host was supposed to support itself using land and other economic privileges, such as fishing rights, bestowed by the tsarist regime. But the state was distributing millions of rubles in grants or loans to replace Cossack uniforms and equipment and to aid over-burdened households stricken by poor harvests. In some communities, a growing population and influx of non-Cossacks had reduced land supply, while rising costs of arms and horses and new standards of equipment imposed after the regularisation of Cossack forces in 1870 increased outlays.

Historian Robert McNeal concluded that in an era of economic and military modernisation, the Cossack estate was an expensive anachronism, propped up by the monarchy to deal with growing internal unrest generated by the stresses of the modernising process. The Cossackry, however, would outlive the tsarist regime.

Cossacks in War and Revolution↑

Conflict and Solidarity↑

In the late 19th century, Cossacks were deployed in border patrols and garrisons in the Caucasus, Central Asia, Siberia, Poland, Ukraine and Lithuania. They contributed tens of thousands of troops for the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-78 and the ill-fated conflict with Japan in 1904-05. An enduring popular image of the Cossacks, however, is as fearsome mounted police, suppressing disorder in the Russian heartland. Large numbers were assigned to internal security as revolutionary unrest escalated from the 1880s and spread across the country in 1905. Eyewitness accounts recall the terror of charges by Cossacks wielding whips on crowds of protesting peasants and workers.

Shane O’Rourke noted, though, that the 1905 Revolution was also a traumatic experience for the Cossacks. Thousands of men were taken from farms facing ruin to conduct a vicious campaign of repression that they personally found revolting. Mutinies broke out within Cossack regiments and spread to their home territories. Cossack deputies to the new Russian parliament, the Duma, complained bitterly about police service.

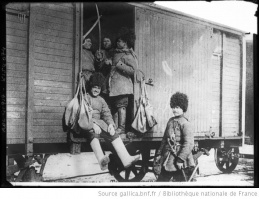

There was no such objection to mobilisation for the First World War, but it took a heavy toll. Cossacks supplied a disproportionately high number of soldiers who, with little use for cavalry, fought alongside peasant soldiers in the misery of the trenches. Casualties reached 12 percent of those mobilised. Women left behind struggled to feed their families. During the overthrow of the monarchy in the February Revolution of 1917, war-weary and impoverished Cossacks surprised everyone by siding with workers and ordinary soldiers against the regime. Almost immediately, though, divisions erupted between Cossack and non-Cossack populations on host territories, between Cossacks of different faith, generation and gender and between radicalised rank-and-file Cossacks and more conservative elites, who in August 1917 supported the authoritarian coup attempt by General Lavr G. Kornilov (1870-1918).

McNeal surmised that the war unleashed the dissolution of the Cossacks. O’Rourke identified countervailing trends, however, in the elevation of Cossack identity. After the February Revolution, Cossack committees formed within the army and the hosts drew on democratic traditions to establish organs of self-government, declaring independence from Russia when the Bolsheviks assumed power.

Civil War and Decossackisation↑

The Civil War resulting from the Bolshevik takeover devastated Cossack homelands, transforming them into battlefields on which more than 1 million men, women and children perished, making the losses of the First World War pale into insignificance. Rifts within Cossack society meant that few initially rallied to their governments’ calls to defend their territories against Bolshevik forces. Many, especially those who had been at the front, welcomed slogans of peace and Soviet power, while others were concerned with local conflicts between Cossacks and non-Cossacks.

Disillusionment with the one-party dictatorship and horror at the violence of Bolshevik punitive expeditions by spring 1918, however, sparked armed resistance, although Cossacks fought alongside both the Red and White armies. In Siberia and the Far East, individual settlements were fiercely defended and brutal reigns of atamans established, while identification with an overarching Cossack community evaporated. In longer-standing hosts of European Russia, such as the Don, hostilities were accompanied by the creation of regular armies mobilised in the name of Cossack independence.

The concept of a separate Cossack people also shaped the Bolsheviks’ shift in early 1919 from a policy of removing Cossack estate privileges and punishing counterrevolutionary action to indiscriminate terror against Cossacks as a suspect population. As Red Army regiments pressed into Cossack territory, thousands of Cossacks were executed by revolutionary tribunals. The policy of physical extermination of the Cossacks was renounced as the Red Army retreated towards Moscow. Eventual Bolshevik victory, however, sparked the emigration of tens of thousands of Cossacks, the dismantling of collective Cossack legal and administrative structures, famine on Cossack territory and the targeting of Cossacks for deportation as part of Stalin’s dekulakisation and collectivisation campaigns, breaking surviving Cossack communities through the loss of farms and people.

Significance↑

The Cossack experience was both a singular tragedy and a microcosm of processes defining early 20th century Russia. These include the crises of modernisation, social polarisation, under-governance and loss of pillars of support that beset the last tsar; the fracturing of authority and redefinition of identities that followed the February Revolution; and the brutalising impact of war that shaped social engineering politics in Russia and beyond.

Siobhan Peeling, University of Nottingham

Section Editors: Yulia Khmelevskaya; Katja Bruisch; Olga Nikonova; Oxana Sergeevna Nagornaja

Selected Bibliography

- Holquist, Peter: 'Conduct merciless mass terror'. Decossackization on the Don, 1919, in: Cahiers du monde russe. Russie, Empire russe, Union soviétique, États indépendants 38/1, 1997, pp. 127-162.

- McNeal, Robert Hatch: Tsar and cossack, 1855-1914, New York 1987: St. Martin's Press.

- O'Rourke, Shane: The Cossacks, Manchester; New York 2007: Manchester University Press; Palgrave.

- Sholokhov, Mikhail Aleksandrovich, Murphy, Brian (ed.): Quiet flows the Don, New York 1996: Carroll and Graf Publishers.

- Trut, V. P.: Kazachestvo Rossii v period Pervoi mirovoi voiny (Russia's cossacks in the First World War), Rostov-na-Donu 1998: Izd-vo 'Gefest'.