The First Diplomatic Steps↑

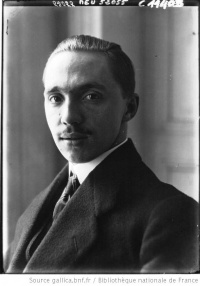

Sixtus, Prince of Bourbon-Parma (1886-1934) was the older brother of Zita, consort of Charles I, Emperor of Austria (1892-1989), the last Empress of Austria-Hungary. Despite being raised in Austria, Zita’s brothers chose different sides when the First World War broke out: Elias, Duke of Parma (1880-1959), Felix, Prince of Bourbon-Parma (1893-1970) and René, Prince of Bourbon-Parma (1894-1962) joined the Austrian army, but Sixtus and Xavier, Prince of Bourbon-Parma (1889-1977) felt themselves obliged to defend the borders of France and joined the Belgian army, not being allowed, as members of a ruling House, to become French officers.

Charles I, Emperor of Austria's (1887-1922) interest in peace became clear immediately after he ascended the throne in 1916. In contrast to Francis Joseph I, Emperor of Austria (1830-1916), Charles did not feel that he was obliged to always act in concert with Germany. On 29 January 1917, the two Belgian officers, Sixtus and Xavier, met their mother, Maria Antonia, Duchess of Bourbon-Parma (1862-1959), in Neuchatel, Switzerland. Acting on behalf of her son-in-law, the Austrian Emperor, their mother presented them with a letter from Charles I. as proof of his willingness to negotiate a separate peace between Austria-Hungary and the Entente. Meanwhile, the princes agreed to the minimum requirements of the Entente Cordiale, namely restitution of Alsace-Lorraine to France, restoration of Belgium and Congo, restoration of Serbia (enlarged with Albania), and the cession of Constantinople to Russia.

The Austro-Hungarian Minister of Foreign Affairs, Ottokar Graf Czernin (1872-1932), was informed of the potential separate peace. Thomas Graf Erdödy (1886-1931), a personal friend of Charles I, was charged with contacting the Bourbon princes and delivering the imperial answer to the Allied proposal. He proposed an independent south-Slavic state and offered to pressure Germany on the question of Alsace-Lorraine. Sixtus transmitted this message to the French President, Raymond Poincaré (1860-1934), who informed his Prime Minister, Aristide Briand (1862-1932), George V, King of Great Britain (1865-1936), and the British Premier David Lloyd George (1863-1945). On 23-24 March 1917, Sixtus and Xavier secretly met the Austrian Emperor and Czernin in the castle of Laxenburg to continue negotiations. On this occasion Charles addressed a letter to Sixtus in which he empowered him to inform Poincaré about his intention to support the French demands concerning Alsace-Lorraine. In the meantime, however, Alexandre Ribot (1842-1923) had replaced Briand as French Prime Minister and was less interested in a separate peace with Austria-Hungary. The Italian Minister of Foreign Affairs, Baron Sidney Costantino Sonnino (1847-1922), also added to the difficulties by insisting on the maximum cession of Austrian territory, namely South Tyrol reaching to the border of the Brenner mountain, parts of Istria including Trieste and half of Dalmatia.

On 4 April 1917, Charles informed Wilhelm II, German Emperor (1859-1941) about the opening of treaties without giving any details. On 8 May 1917, Sixtus visited Charles for the second time in Laxenburg and proposed separate peace treaties without including Germany. In a second letter Charles showed himself willing to cede the Italian-speaking parts of Tyrol to Italy. However, after returning to France to continue negotiations with the leading French and British politicians, Sixtus was unable to convince them to agree to the separate peace; Sonnino was not willing to change his mind, and the French and British governments refused to put any political pressure on their Italian ally.

Czernin provokes a political scandal↑

On 2 April 1918, after the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk had been signed, Czernin was solemnly received by the Council of the City of Vienna, where he declared that the only obstacle to peace was the French pretensions to Alsace-Lorraine and insisted that the French Government had started secret negotiations with Austria to arrange a separate peace. During the following days, the so-called “Sixtus-Affair” led to Czernin’s downfall. The French press responded immediately by publishing Emperor Charles’ letter – which Czernin knew about - to his brother-in-law Sixtus, in which Charles assured him that he would support the “just demands” of France concerning Alsace-Lorraine. On 14 April 1918 Czernin retired after arguing with Charles I.

The affair highlighted not only a generational shift from Francis Joseph I to Charles I, but also that the time for Kabinettpolitik – a policy of secret negotiations behind closed doors - had passed. The Sixtus Affair, as it came to be known, led Austria to become increasingly dependent on Germany in the following months.

Robert Rill, Austrian State Archives/War Archive

Section Editor: Tamara Scheer

Selected Bibliography

- Brook-Shepherd, Gordon / Eidlitz, Johannes: Karl I. Des Reiches letzter Kaiser. Glanz und Elend des letzten österreichischen Herrscherpaares, Vienna; Munich 1976: Molden Taschenbuch Verlag.

- Demblin, August / Demblin, Alexander: Minister gegen Kaiser. Aufzeichnungen eines österreichisch-ungarischen Diplomaten über Aussenminister Czernin und Kaiser Karl, Vienna 1997: Böhlau.

- Demmerle, Eva: Kaiser Karl I. 'Selig, die Frieden stiften-'. Die Biographie, Vienna 2004: Amalthea.

- Feigl, Erich: 'Gott erhalte-' Kaiser Karl. persönliche Aufzeichnungen und Dokumente, Vienna 2006: Amalthea.

- Kann, Robert A.: Die Sixtusaffäre und die geheimen Friedensverhandlungen Österreich-Ungarns im Ersten Weltkrieg, Vienna 1966: Verlag für Geschichte und Politik.