Introduction↑

Imperialism shaped the content and the structure of international politics from 1898 to 1914. Six wars - the Spanish-American, the Boer, the Russo-Japanese, the Italo-Turkish, and the two Balkan - profoundly altered power relationships. Three major international crises - two Moroccan crises (1905–1906 and 1911) and the Bosnian annexation crisis (1908–1909) - transformed international politics as the Triple Entente emerged to challenge the older Triple Alliance. Threats of war in the Balkans in 1912–1913 with Austria-Hungary against Serbia or against Montenegro or against Russia presaged events after the assassination. Coupled with imperialism were a dynamic armaments race (naval and military) and increasingly virulent nationalism. These developments did not necessarily make war inevitable; the great powers consistently managed to contain the situation. But two shots in Sarajevo changed the nexus of an “improbable war.”[1]

Imperialism Realigns European Politics, 1898–1907↑

On 15 February 1898 the USS Maine exploded in Cuba’s Havana Harbor, signifying the beginning of the Spanish-American War. Within months the United States defeated an old imperial power, Spain. The Philippines, Guam, Puerto Rico, and Hawaii were now American, and Cuba became an American protectorate. A confident United States soon proclaimed the Open Door Policy for China in an effort to stop that country’s partition by the European powers and Japan. In November 1901 London renounced any claim on construction of a canal in Central America. Britain had begun its retreat from universal imperial intentions and the United States was now a world power.[2]

Two other events in 1898 also influenced British policy. On 3 March 1898 the German Reichstag passed the first of Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz’s (1849–1930) naval bills, calling for a sharp increase in naval spending. While Tirpitz privately envisioned the naval construction to be aimed specifically at Britain, London was not immediately alarmed. Wilhelm II, German Emperor’s (1859–1941) grandiose talk of Weltpolitik (“world policy”) and seizure of the Chinese port of Kiaochow provided ample rationale to ramp up the navy. Only later did German naval proliferation threaten Anglo-German relations.

The late summer of 1898 saw a third seminal event for London, far away on the upper Nile at an obscure site called Fashoda. Here British troops confronted French troops led by Captain Jean-Baptiste Marchand (1863–1934), who had crossed much of Africa in a desperate attempt to gain leverage against the British in Egypt and Sudan. Talk of war came and then faded. British naval supremacy, as well as French political chaos after the Dreyfus Affair, led Paris to yield to London.[3]

Rather than fight, the new French foreign minister, Théophile Delcassé (1858–1923), abruptly shifted his strategy. Morocco, not Egypt, became his intended conquest. First, he squared the situation with the Italians, recognizing their future rights to Tripoli. He offered nothing to Germany, even though it was a signatory to an 1880 treaty guaranteeing Moroccan independence. Most crucially, Delcassé instructed the new French ambassador in London, Paul Cambon (1843–1924), to improve Anglo-French relations. Fashoda had opened the door to better Anglo-French relations.

London did not fare well in the years after the Fashoda incident. The three-year Boer War (1899–1902) divided British society, but the army’s initial incompetence eventually turned to victory. On the Continent there was loose talk about intervention in the Boer War. Suddenly Britain’s imperial possessions appeared vulnerable; their splendid isolation had become lonely and also dangerous.[4]

The Russians, meanwhile, pressed their territorial aggressiveness in the Far East, thus angering the Japanese and alarming the British about their position in India. To offset these threats, Henry Petty-Fitzmaurice, Marquess of Lansdowne (1845–1927), the British foreign secretary, made a wholly unexpected move, negotiating a defensive alliance with Japan in January 1902. This agreement, made with a non-European, non-Anglo-Saxon power, marked a profound departure for Britain. It strengthened Britain’s position in the Far East and allowed some realignment of British naval forces.

Lansdowne did not stop there; he now turned his attention to Paris. The enthusiastic reception given Edward VII, King of Great Britain (1841–1910) on his Paris visit in May 1903 helped. Negotiations followed; the outlines of an imperial deal were soon in place. France conceded Egypt to Britain and the British pledged to support French efforts to control Morocco. The two countries also resolved long-standing disputes about fishing rights off Newfoundland. Signed on 8 April 1904, the agreement did not go to British parliament for ratification and it had no military dimensions. The agreement represented imperialism at its zenith.[5]

Just weeks before the conclusion of the entente (as the agreement between France and Britain came to be called), Britain’s ally, Japan, launched a surprise attack on the Russians at Port Arthur. At no point in the ensuing Russo-Japanese War did either the French or the British consider intervention. The land struggle in Manchuria proved costly, with the Japanese finally prevailing. The humiliating defeat of Russia’s Baltic Fleet at the Battle of Tsushima in late May ended the war. In Russia virtual revolutionary conditions erupted. Nicholas II, Emperor of Russia’s (1868–1918) very reign was in doubt. Under pressure he agreed to the creation of a parliamentary body, the Duma, but he soon worked hard to undermine his own concession.

London tracked these events carefully. Russia’s defeats eased the threat to India. Soon the British Foreign Office saw another opportunity. The new British foreign secretary Sir Edward Grey (1862–1933) wanted to ensure Britain’s imperial position. Sir Arthur Nicolson (1849–1928), the British ambassador to Russia, opened negotiations with Alexander Izvolsky (1856–1919), the new Russian foreign minister, on a range of issues including Persia and the Indian frontier. The two countries came to an agreement, again called an entente, in August 1907; this represented another British success in securing its imperial realm. Though the agreement was touted as anti-German in origin, it really grew out of imperial interests. Like the French accord, it had no military component. Yet taken together, the two agreements represented a fundamental shift in London’s relationship with its two former antagonists. Paradoxically, within months the Triple Entente, though never precisely called that by Grey and the Foreign Office, began its subtle evolution into a more distinctly anti-German alignment. Austria-Hungary was the Triple Entente’s secondary - and nowhere near as worrisome - concern.[6]

While London looked after its empire, German leaders talked incessantly of Weltpolitik. With Europe’s second largest economy and technological advantages, Germany had become the continental power. Kaiser Wilhelm’s rule continued, though Chancellor Prince Bernhard von Bülow (1849–1929) managed to curb some of his worst excesses.

The continuation of the Russo-Japanese War and French moves toward Morocco suggested another approach to Berlin’s policymakers. Recent research shows that Berlin attempted to disrupt the new entente while also making overtures to Russia. Both efforts failed, the first more spectacularly and dangerously than the second.[7]

Delcassé had purposely ignored the 1880 international treaty signed by fourteen countries including France, Germany, Britain, Italy, Austria-Hungary, and the United States. In early 1905 he and the French leadership expanded their peaceful penetration into Morocco, which alarmed Berlin. The German leadership decided to remind France of its international commitments to Morocco and to test the entente in the process. But Berlin failed to be subtle in this maneuver. Every spring Wilhelm travelled to the Mediterranean; this time the Wilhelmstrasse (the German Foreign Office) convinced the reluctant Kaiser to land at the Moroccan port of Tangier. There he would assure the sultan of German support. The 31 March visit marked the start of the first Moroccan crisis. From April to June some feared the prospect of war. When the new French premier, Maurice Rouvier (1842–1911), saw no chance of victory, he ousted Delcassé and accepted an international conference. Germany had won the first round, but during the summer of 1905 German diplomatic aggressiveness managed to alienate Rouvier, as well as the British Foreign Office and Lord Lansdowne. Moving deftly, French Ambassador Cambon worked to push the British into open support as the quid pro quo for the Egyptian concession. Lansdowne disliked the blackmail but did not totally reject it. Grey entered the scene as Lansdowne’s successor in the new Liberal Cabinet in December 1905, and he agreed with Lansdowne and moved even closer to Cambon’s views.[8]

As the crisis developed, still more important actions were underway in London. Admiral Sir John Fisher (1841–1920), first lord of the admiralty, who had previously ignored the German navy, talked privately of a preemptive attack on it. Then, in late December 1905, secret military conversations between the British and French armies started. What had once been just an imperial treaty now developed into the possibility of British military assistance to buttress French imperial claims. These secret conversations were kept from the Cabinet; only Grey, Prime Minister Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman (1836–1908), and Richard Burdon Haldane (1856–1928), secretary of state for war, knew of them. Indeed, it took until fall 1911 for the entire British Cabinet to learn of them.

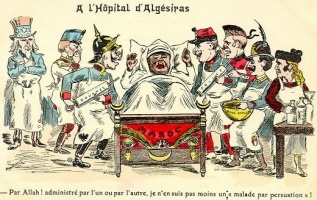

Soon the crisis passed. The Conference at Algeciras in early 1906 ended the standoff, giving the French certain police functions in Morocco, though not complete control. Berlin still retained some leverage but the advantage had shifted to France. Perhaps more significantly, a military dimension had been added to the imperialistic entente and it had survived the German attempt to disrupt it.[9]

The second German initiative, pulling Russia away from the French, also failed. In the summer of 1905 Kaiser Wilhelm II and Tsar Nicholas II met in the Gulf of Finland. The much-chastened tsar found a solicitous cousin proposing a major revamping of Russo-German relations. The Treaty of Björkö, which Nicholas readily signed, gutted the alliance with France. But when the tsar returned to St. Petersburg, his officials convinced him that the new agreement ruined the French alliance and would deprive them of desperately needed French capital. The submissive tsar informed Berlin and turned to face the domestic chaos in Russia.

Three additional observations about the critical years from 1898 to 1907 are necessary to understand the strategic revolution taking place. First, in 1905, General Alfred von Schlieffen (1833–1913) completed the first draft of his famous war plan. While commentators have recently argued that it was fundamentally a plea for additional troops and could only work with a defeated Russia, the plan and its basic parameters shaped subsequent German military planning. In 1906 the new chief of the Prussian General Staff, Helmuth von Moltke (1848–1916), used the war plan as the starting point for his later changes. Schlieffen had set the course, for better or worse.[10]

Second, the years after 1905 saw a profound change in the British Foreign Office. By 1907 suspicion about any German action was the rule of thumb. This attitude did not prevent negotiations with Germany over naval issues, but the bureaucratic apparatus under Grey construed every German action from the worst possible angle.[11]

A third strategic consideration also intruded on British security concerns. The recently created Committee of Imperial Defence examined the question of a possible German invasion. More importantly, some British army officers thought British troops might be on the Continent. The Anglo-French entente was not yet an alliance, or even a virtual alliance. Still, it had become more than simply an imperial division of the spoils.

1907–1911: Europe in Transition and Division↑

In 1906 two new foreign ministers took office: Izvolsky in Russia and Alois Lexa von Aehrenthal (1854–1912) in Austria-Hungary. The interaction of these two shaped much of European diplomacy from 1906 through the summer of 1909. In the end the two men ensured their countries would be permanently estranged.[12]

Of the two, Izvolsky had the more difficult task as he worked to recast Russian foreign policy from its disastrous fixation on expansion in the Far East. Not surprisingly, he returned to two previous areas of Romanov imperial interest: the Balkans and the Straits at Constantinople. As he shifted Russia’s focus, Izvolsky had some unexpected assistance. In Serbia a bloody coup d’état in 1903 ended the Obrenović dynasty and brought Peter I. Karadjordjević (1844–1921) to power. By 1906 Austro-Serb relations, once modestly agreeable to Vienna and Belgrade, had deteriorated into nasty exchanges and an unfortunate “Pig War” over pork imports into the Danubian monarchy. The schism between the two neighbors grew progressively wider, which in turn offered the Russian minister new possibilities.

A second factor also helped Russia’s cause: Turkish power in Macedonia and the Balkans appeared weaker than ever. Covetous eyes now turned toward possible gains at the Straits and perhaps elsewhere. A third factor also gave Izvolsky confidence: London’s decision to negotiate with Russia on Persia and the implicit protection of Britain’s position in India. The new Anglo-Russian entente protected Russian interests without surrendering the possible future resumption of expansion.

The ambitions of Alois von Aehrenthal for Austria-Hungary also emerged as a factor in Russia’s foreign policy. Having been the most recent Habsburg ambassador to Russia, Aehrenthal wanted to restore the monarchy as a great power. The heir-apparent Franz Ferdinand, Archduke of Austria-Este (1863–1914) advocated the appointment of Aehrenthal and the new Habsburg chief of staff, General Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf (1852–1925), to the his uncle, Francis Joseph I, Emperor of Austria (1830-1916). Both Aehrenthal and Hötzendorf marked a generational shift in Vienna’s leadership. The new men wanted to make their imprint upon Habsburg history and both did - but not with altogether pleasing results.

Aehrenthal had two specific policy objectives: to construct rail lines linking the monarchy with Turkish railways, enhancing the monarchy’s position in the Balkans; and the formal annexation of Bosnia and Herzegovina into the monarchy. Movement on the rail lines immediately drew Russian attention. Then, in mid-summer 1908, the Young Turk revolution in Constantinople raised fears in Vienna that the Young Turks would seek to undermine Austria’s protectorate status over the two provinces.

Izvolsky also fretted about developments in the Turkish capital. A stronger government there would hurt Russian interests. His concerns aligned with those of Aehrenthal. The two ministers agreed to meet at the Buchlau estate in Moravia, the home of Habsburg ambassador to Russia, Leopold Graf Berchtold (1863–1942). In the talks Izvolsky accepted the formal annexation of Bosnia and Herzegovina while Vienna pledged to back Russian demands for passage of its warships through the Straits. Izvolsky and Aehrenthal also agreed, almost as an afterthought, to accept Bulgaria’s status as an independent kingdom, no longer submissive to the Turks in any way. The two had reached an imperial accord.

Had their deal succeeded in strengthening - not ruining - Austro-Russian relations, a wholly different Balkan scenario might have emerged. But the agreement almost immediately unraveled. Both ministers misplayed their opportunity, each soon accusing the other of treachery. Before Izvolsky could complete his scheduled travels in western Europe, Aehrenthal decided to act, alarmed by news that Bulgaria intended to proclaim its independence from Turkey far ahead of schedule. He probably also wanted to celebrate his success by announcing the annexation on 5 October at a meeting of the Habsburg Delegations, the closest thing to an imperial parliament. In any event, Aehrenthal’s premature declaration left Izvolsky exposed, for the Russian had not prepared the tsar or his ministerial colleagues for the Buchlau deal. Pan-Slavic groups denounced the betrayal of Bosnian Serbs for no appreciable gains at the Straits.[13]

The Bosnian crisis over the next five months represented a kind of prelude to the July crisis of 1914. Numerous Russian, Habsburg, and Serbian troops were called to the colors; war seemed a real possibility. The tension persisted, finally ending when St. Petersburg told the Serbs to capitulate in March 1909. That reversal had only come after a strong threat from Berlin of German intervention if the crisis continued.

Why was peace maintained in 1909, when it could not be five years later? Three factors assisted in preserving the peace. The Russian army remained weak from its defeats at the hands of the Japanese. The Russian leadership’s realistic recognition of its own weakness helped. Further, neither France nor Britain gave more than token support to Russia; the ally and the new entente partner viewed the annexation of Bosnia and Herzegovina as simply ratifying arrangements already conceded at the Congress of Berlin in 1878. Third, Aehrenthal and Franz Ferdinand did not want war - Conrad von Hötzendorf notwithstanding - and they listened carefully to their Berlin and Rome allies who also opposed war.

The annexation tumult ended fifteen years or more of cooperation between Vienna and St. Petersburg over the future of the Balkans. Once collaborators, they were now ferocious competitors; as such, the future chances of even détente between the two were remote. Serbia had been forced to pledge it would keep South Slavic propaganda under control, but these promises were not honored. The Narodna Odbrana (Serbian National Defense) continued its activity, only more cautiously. A group behind the 1903 regicides, led by Serbian major Dragutin Dimitrijević (1876–1917), founded the secret society Black Hand (Ujedinjenje ili smrt) in 1911, dedicated to using any means, lethal or otherwise, to bring about the union of all South Slavs.[14]

As tensions eased, European diplomacy in 1909 and 1910 enjoyed almost two years of relative calm. The Anglo-German naval race intensified and armaments now joined imperialism as the second theme influencing international politics. There were periodic efforts to curb the naval race, prompted in part by political needs in both countries. The new German chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg (1856–1921) wanted to slow growing naval expenditures. So too did some in the British Cabinet. But the efforts to slow the race failed; each country continued to trumpet construction of the new dreadnought class of battleships.[15]

The Agadir Crisis and Its Aftermath↑

In Paris, meanwhile, in spring 1911, officials in the French Foreign Office decided the time had come to seize Morocco. New domestic unrest in Morocco provided the excuse to intervene to protect foreigners. French troops went to Fez; the Germans protested and went silent and then carefully plotted their next move. Then on 1 July Berlin raised the stakes in one fell swoop. A German gunboat, the Panther, arrived at the port of Agadir, on the Atlantic side of Morocco. The second Moroccan crisis had begun, only ending in early autumn when the Germans conceded defeat, receiving extensive territory in the French Congo as consolation. Berlin had once again been bested.[16]

The Agadir crisis prompted another incremental but substantive change in Anglo-French relations. After some hesitation, London publicly backed French claims and left Berlin in no doubt of its position. Far more concealed were accelerated talks between the British General Staff’s director of military operations, Brigadier General Henry Wilson (1864–1922), and French staff officers. Indeed, Wilson arranged detailed plans for possible British intervention. On 23 August a rump meeting of the Committee of Imperial Defence saw General Wilson and Admiral Arthur Wilson (1842–1921), first sea lord of the admiralty, outline their plans for war. In every instance the general out-dueled the admiral. While no formal decision was reached, the civilian ministers accepted the prospect of a British army on the Continent. Still, they also agreed that the Cabinet retained the final say.

This meeting had three additional consequences. The performance of Reginald McKenna (1863–1943), the civilian head of the navy, was so dismal that Winston Churchill (1874–1965) managed to maneuver his own appointment as first lord of the admiralty. This meant that a Continentalist was now a part of the national security structure. The second consequence was less pleasant: Grey and Prime Minister Herbert Henry Asquith (1852–1928) faced a virtual Cabinet rebellion when the more radical members learned of the secret military conversations between Paris and London. Grey promised to put some restrictions upon the talks but refused to stop them; the restrictions were meaningless. Finally, the crisis, which had started as an imperial dispute, demonstrated how the entente had now become a constant factor in European politics. If Britain did not have an alliance with France, the entente’s steady evolution with its diplomatic and now military consequences made it a “virtual” alliance. Already, when the Dominion prime ministers had gathered in London in spring 1911 for the coronation of George V, King of Great Britain (1865–1936), Grey essentially told them Britain was committed to a Continental policy. In the autumn of that same year, he and the Liberal Imperialists in the Cabinet clearly had the upper hand over their more radical and liberal colleagues.[17]

In Paris, the Agadir crisis brought the dismissal of General Victor Michel (1850–1937) because of his proposed defensive strategy against Germany. His departure led to the complete revamping of the French staff system. Henceforth the chief of general staff was also responsible for drafting the war plans, thus consolidating power in the hands of one general. The new chief, General Joseph Joffre (1852–1931), took charge. His most immediate contribution came when he bluntly told the civilians to make a deal with Germany. By mid-autumn peace had been preserved.[18]

Meanwhile, in Rome, different and more dangerous machinations were underway. The Italian government had watched apprehensively as the French advanced on Fez. By August Prime Minister Giovanni Giolitti (1842–1928) and Foreign Minister Antonino San Giuliano (1852–1914) concluded that Italy had to seize Tripoli from the Ottomans - the sooner the better. Yet the ministers were warned that any Italian move against the Turks almost certainly ensured trouble in the Balkans. Already Serbian and Bulgarian guerrilla forces were attacking Turkish posts and each other in Turkish Macedonia. But the Italian leaders simply brushed these concerns aside. In fact, the leadership also ignored warnings from their own military commanders that the army was not ready for war.[19]

War there would be. A formal declaration came on 29 September 1911 and Italian forces landed, largely without much initial opposition, on 3 October. The early gains, however, were not followed by additional success. Soon the Italians found themselves confronted with stubborn Turkish and native resistance; the Turkish government did not immediately sue for peace. A frustrated Italian leadership nevertheless proclaimed the annexation of Tripoli and other areas of what is present-day Libya on 5 November even as the fighting continued. Eventually, the Italians expanded military operations against the Ottomans into the Aegean Sea, causing severe friction with Paris and alarming the British and Germans. Only with the threat of a Balkan War, endangering both Italian and Turkish interests closer to home, did peace come on 18 October 1912.

The importance of the Italian attack can hardly be overemphasized. The premonitions that the Balkan states might move against the Ottoman holdings in Europe proved deadly accurate, for the Balkans were soon in play. The Russians led the way through the agency of their minister in Belgrade, Nicolai Hartwig (1857–1914). By late spring a secret Balkan League that included the Serbs, the Bulgarians, and the Greeks had emerged. The grouping aimed to drive the Ottomans out of the Balkans and position the group for similar, later action against Austria-Hungary. Imperialism and imperial concerns had reached the Continent. The only question remaining was: when would the war begin?[20]

The Balkan League was not the only important consequence of the Agadir crisis. In Berlin conservative critics assailed their government for the paucity of its gains: worthless African land and no position in Morocco. The Prussian Army concluded that it needed more men. Thus began the first round of the army’s push for additional troops, efforts that proved so successful that by 1914 the strength of German forces had increased to 890,000 men on active duty. The German gains, in turn, necessitated French and Russian efforts, so that the two allies had added an additional million men by 1914. The need for more army funds put Bethmann Hollweg and the German government under financial pressure; the German chancellor wanted to slow down the naval race.[21]

In London similar pressures existed, as Grey needed to show the radicals in the Cabinet that Anglo-German relations might still be improved. After much preliminary maneuvering, the Cabinet agreed to send Lord Haldane, former war secretary and now lord chancellor, to Berlin. Haldane, who spoke German fluently, was a well-known figure among the German leadership. Haldane met with Kaiser Wilhelm, Bethmann Hollweg, and Tirpitz. They gave him a copy of the new naval law. More critically, they offered to slow the construction program if Britain pledged benevolent neutrality in a European war. Haldane countered with a promise not to participate in an unprovoked attack on Germany, a deal Berlin would not accept. When Haldane returned to London, Churchill and the naval staff concluded that the new law posed an even greater threat to British security than they had anticipated. The bottom line was simple: a 33 percent increase in German ships in active service. Britain could only meet this new threat by repositioning ships, especially from the Mediterranean. Clearly the talks had failed and naval construction continued apace in Britain and Germany.[22]

1912–1913: The Balkans Reshape European Diplomacy↑

In January 1912 Raymond Poincaré (1860–1934) became French premier and foreign minister, a position he held until he was elected president of France in February 1913. The impact of his ascent to power was immense. A Lorrainer whose homeland had been taken by the Germans, Poincaré had a visceral, negative reaction to most things German. His overriding objective was to strengthen French security against Germany.[23]

In 1912 Poincaré blocked plans advocated by General Joffre for a French offensive through Belgium; the foreign minister would not risk British help in case of war. From early spring to late fall he pressed for an alliance with London, or if not an alliance, a more definite assurance of British assistance. He cleverly exploited Churchill’s decision to realign naval forces in the Mediterranean by declaring French forces would withdraw from the north and go to the Middle Sea. Put another way, he implied that France would protect British interests in the Mediterranean while the British did the same for France in the north. Though Churchill explicitly rejected this interpretation, Poincaré had created a marker with London that would be used during the July crisis. At the same time more detailed military conversations took place between General Wilson and his French counterparts.

But try as he might, Poincaré and Paul Cambon could not get Grey to agree to an alliance. The Cabinet, the foreign secretary repeatedly explained, would never consent. In November Grey and Cambon exchanged letters that acknowledged the previous military and naval conversation and pledged cooperation in time of a crisis. The radicals in the Cabinet believed they had restrained Grey, while the French believed the British had edged closer to the Continent. The imperialistic entente had now become a de facto alliance.[24]

Poincaré also worked to buttress ties with Russia, traveling there in mid-1912, and having Joffre go there that summer. The French wanted the Russians to accelerate their mobilization schedules and thus threaten German forces more quickly from the east. Poincaré did not come empty-handed. France bankrolled extensive improvements to the Russian rail system and funded other aspects of Russian rearmament. In the frenzy of armaments spending after 1911, French banks had seemingly inexhaustible funds to help Russia and later Serbia.[25]

In the summer of 1912 Vienna and Budapest took an unusual step: the two governments actually agreed to increase army strength for the first time since 1889. The Habsburg monarchy had joined the armaments race. Then in late summer, Berchtold, now aware of the Balkan League, sought to summon the so-called European Concert of Powers to discuss further Ottoman reforms in Macedonia that might avert military conflict. He got precious little support for this effort, even from his German ally. By late September war in the Balkans appeared inevitable - and it did break out in due time.

The Montenegrins declared war on 8 October, followed by the Serbs, Greeks, and Bulgarians on 18 October. As the fighting started, Russia kept 200,000 additional troops on active duty in western Russia following the summer maneuvers. Vienna quickly found itself on the defensive. Berchtold’s first assumption, that the Turkish forces would hold their ground, proved wrong. The Balkan armies soon chased Turkish forces from large parts of Macedonia and Albania and appeared set to go all the way to Constantinople. Confronted with this turn of events, the Habsburg leadership adopted a double strategy: increase troop strength in Bosnia-Herzegovina to prevent any Serbian incursion into its imperial provinces while eventually, in November, increasing troop strength in the frontiers against Russia. Rather than mobilize, they steadily increased their active duty forces. Eventually in the south they nearly reached full strength, at a cost of almost a year’s regular budget.

Berchtold’s second objective focused on blocking any Serbian access to the sea. To do this he played the Albanian card, finally getting the European Concert to agree to the creation of Albania as a state with defined borders. In this effort he had support from all of the powers, though Russia hedged at every turn. Eventually, in early December, Grey convened a conference of ambassadors in London to negotiate peace terms between the Balkan states and the Ottomans and among themselves and to sanction the creation of the new state of Albania. A truce ensued, and then more fighting before a final accord was reached in May 1913. The general peace had been maintained.[26]

But there were dangerous moments during the eight months of the first war. From December to May the Habsburg decision makers considered the question of war three times: first against Serbia if Serbian troops moved toward the two provinces; then in May against tiny Montenegro over an Albanian border dispute; and lastly, and more dangerously, against Russia during the dead of winter. Prudence in Vienna, clear signals from Berlin to be careful, and skillful negotiation in February brought a reduction of Russian and Habsburg troop strength. On the other hand, both powers drew a singular lesson from these events: militant diplomacy worked. Indeed, when Vienna issued a seven-day ultimatum to Serbia in October 1913 to abandon territory assigned to Albania, Belgrade capitulated. Again, Vienna concluded that the threat of force worked, an axiom that dominated its strategy eight months later.

As the Balkan events unfolded, senior German officials came to some conclusions of their own. At a meeting of some of the senior leadership, excluding Bethmann Hollweg, on 8 December, the group concluded that Britain might enter the war on the side of France and Russia, and Berlin had to plan accordingly. But that conclusion did not mean the Germans were plotting for war; rather, they were assessing Germany’s strategic position. Soon Berlin pressed Vienna to compromise with St. Petersburg and therefore eased the possibility of an Austro-Russian war.[27]

The Germans also moderated European reactions when the Second Balkan War broke out in late June 1913. Bulgaria, angered at its small share of the booty from the Turkish collapse, unwisely decided to attack its former allies. The allies, now joined by Romania, quickly defeated the Bulgarians, causing them to lose still more territory in the Treaty of Bucharest. Still, the fighting had ceased. Unfortunately for Austria-Hungary, its strong position in the Balkans had lost its footing.

The Final Months of Peace↑

In the spring of 1914 Sergei Sazonov (1860–1927) could look back on four years of steady success for Russian policy since his appointment as foreign minister in 1910. A secret agent behind the Balkan League, Sazonov had seen the efforts exceed his highest expectations. Serbia, doubled in size and population, had enhanced his standing with the Pan-Slavs. Moreover, he had just forced Berlin to capitulate and accept changes to the appointment status of General Otto Liman von Sanders (1855–1929) in Constantinople. Rather than command Ottoman troops, Liman von Sanders would instead supervise their training efforts. St. Petersburg, still coveting the Straits, would have less to fear if push came to shove. Further, during the ministerial realignment of the tsar’s government in February, the aged Ivan Goremykin (1839–1917) became premier. However, the real power rested with the agriculture minister, Alexander Krivoshein (1857–1921), who zealously wished for the Straits. Sazonov had a crucial ally.[28]

Another Sazonov effort also showed promise: weaning Bucharest off of its secret accord with the Triple Alliance. Sazonov’s support of the Romanian leader, King Carol I, King of Romania (1839–1914), during the Second Balkan War had helped, as had continuing friction between the Romanian government and Hungary over the status of the three million Romanians living under hostile Magyar rule in Transylvania. In early June the tsar visited the Romanian port of Constanta, with Sazonov provocatively crossing into Transylvania. Romania’s possible defection created new alarms in Vienna, while giving St. Petersburg an additional chess piece.

Relations with Serbia continued on an intimate basis. Minister Hartwig and Serbian Prime Minister Nikola Pašić (1846–1926) were seen together almost daily in Belgrade. With the Turks ousted, Hartwig now focused his attention on Austria-Hungary. While he cautioned the Serbs that recovery had to come, he stirred the pot of South Slavic irredentism. Still, not all the news from Serbia was pleasant. In the newly conquered lands Serbs persecuted Turks and other non-Turks. More significantly, the civilian and military authorities were in total disagreement over which group should administer the new gains. By late May Pašić and his government had essentially fallen, thanks to the efforts of the army and its hidden supporters in the conspiratorial Black Hand. The crafty Serbian leader only regained power thanks to Hartwig’s intervention, a further sign that St. Petersburg had great influence. Still, even the Russians could not assure Pašić and the civilian leadership that the military would not, as it had in 1903, mount a coup. In Belgrade in June 1914 domestic politics had an unusually fractious aspect as political and military leaders vied for administrative control of the newly conquered Turkish lands.[29]

More reassuring to Sazonov were his ties with the French. Two allies of Poincaré, first Delcassé and then Maurice Paléologue (1859–1944), had come as ambassadors to St. Petersburg. Both men were unequivocal in their support of Russia and of the alliance. French financial assistance for rail construction continued unabated and President Poincaré had scheduled a state visit for July.

The French, moreover, had tried to assist Russia with Britain. In April, when Grey visited Paris, the French pressed for Anglo-Russian naval talks. The foreign minister agreed and got Cabinet assent as well, though he soon publicly denied any such talks were underway. German intelligence quickly learned of the new developments so that Grey’s denials damaged his credibility in Berlin, a consideration that did not help in the July crisis.

Another, far more subtle transformation of Russian (and French) policy was also underway. Paris found itself pulled into the Russian imperial games in the Balkans. Desperate to have Russia threaten Germany, the French now expanded their alliance commitment to an arena far from France. For their part, the British were less committed to Balkan dealings, but the Foreign Office increasingly saw Vienna as an extension of Berlin. The practical effect of this attitude became evident in July 1914, when Vienna found it could make no move of any kind to punish Serbia for the assassination in Sarajevo without confronting unyielding Russian and French opposition.[30]

In 1914 the third partner in the Triple Entente, Britain, focused almost completely on the Irish question. The prospect of Home Rule for Ireland brought paroxysms of anger and despair to the Tory leadership. General Henry Wilson, when not plotting with the French, virtually fomented mutiny during the Curragh incident. These severe domestic tensions led some to think, in July 1914, that a war in Europe might just prevent a civil war in Britain.

Despite the political tensions, in April 1914 Grey traveled to Paris to celebrate the tenth anniversary of the entente. It was his first and only trip outside Britain as foreign secretary. No outsider could doubt the intimacy of London’s ties with Paris. But Britain, despite agreeing to naval talks, was having friction with St. Petersburg over Persia and other colonial issues. Rather than suggest a possible break with St. Petersburg, the Foreign Office renewed its effort to keep the Anglo-Russian entente intact.

Somewhat unexpectedly, Anglo-German relations had entered a period sometimes described as one of détente. Because Britain had clearly won the Naval Race between Germany and Great Britain, naval competition eased between the two countries. Trade remained at high levels and there were talks of a possible way to divide Portuguese colonies in Africa in the future. Wilhelm had fewer personal issues with his cousin, George V, than with his deceased uncle, Edward. Bethmann Hollweg and his associates could not agree on what Britain might do in a crisis, though the chancellor hoped that Britain might stay out. In any event, on the eve of the assassination, ships from both navies gathered at the German port of Kiel in a festive celebration of maritime activity.[31]

In 1914 the Triple Alliance showed less coherence and more internal tensions than its rival, a fact that contemporaries realized. While the alliance itself had been renewed in late 1912, complete with newly-agreed upon military and naval plans, there were problems. Political turmoil in Italy did little to assure confidence, and Austro-Italian tensions increased as they vied openly for the upper hand in Albania. Italian irredentism over the Tirol had resurged. Even a visit by Berchtold in April to see San Giuliano had done little to ease the situation.

In Berlin, the spring of 1914 brought increasing political concerns over the growing power of the Social Democrats; their electoral strength in the Reichstag alarmed the center and right parties. Fallout from the Zabern incident in which a German officer insulted civilians in Alsace and then later German soldiers further retaliated against civilians also reverberated. Russian behavior over the Liman von Sanders’ appointment affair engendered new animosity toward St. Petersburg. Indeed, in March the military press of both countries launched newspaper salvoes at each other. Still more troubling, the Prussian General Staff and the Kaiser expressed almost frantic concerns over the growth of the Russian army and economy. Increasingly, leaders indiscreetly talked of preventive war before Russia’s rearmament would be complete in 1917. These talks appear to have had little influence on the July crisis, but that has not always been the prevailing analysis. These bellicose effusions were cited as proof that Germany almost unilaterally set the pace, a view much overstated and at odds with the new information about French and Russian moves in the months before Sarajevo. Nor does it square with Vienna’s key decisions in July 1914.[32]

Germany also worried, rightly so, about its chief ally: Austria-Hungary. The Balkan Wars had not been kind to the old monarchy; further, Germany and Austria-Hungary disagreed on many aspects of the future. Wilhelm still thought the Romanians could be kept in the alliance; disdained any talk of Bulgaria as a counterweight to Serbia; and even sought to convince Vienna that the Serbs could be contained. The Austro-Hungarians, including Berchtold, István Tisza (1861-1918), and especially General Conrad von Hötzendorf, were less sure. Indeed, even Archduke Franz Ferdinand, a staunch opponent of a military showdown, worried about the future.

Just before Sarajevo, the Ballhausplatz (home of the Habsburg foreign ministry) drafted a new policy that sought to contain Serbia by forging an alliance with Bulgaria and pushing for a final effort to corral Romania. The document called for a more assertive policy, but one that clearly needed financial and moral support from Berlin to assist in the new show of strength. Then came Sarajevo.

The years from 1898 to late June 1914 saw a nearly complete transformation of European diplomacy and the emergence of global international politics. Imperialism and armaments were themes that linked many of the changes. The major actors, especially the Triple Entente powers, took steps that helped to divide Europe into two competing alliances, even if the powers occasionally dealt with members of the other grouping. On the continent, Berlin remained the fulcrum around which Russian, French, and Habsburg policy revolved. But the centrality of Germany’s position did not make it the only actor; its three neighbors also had their agendas. The British, though always mesmerized by imperial concerns, gradually but steadily linked their fortune to those of France and Russia. However much Grey might pretend, even to himself, that Britain was not committed, the facts and milieu suggested otherwise. Still more critical in the July crisis, Grey’s central role in keeping the Liberal government in power gave him clout. If he left in a huff because Britain did not help France, the Cabinet would almost certainly collapse and a Tory-Liberal Imperialist coalition would come to power.

If Grey played a key part in London, Foreign Minister Berchtold was his counterpart in Vienna. The de facto imperial chancellor, Berchtold’s decisions would shape the Habsburg response. The aged Emperor Francis Joseph would almost certainly accept whatever course Berchtold advocated.[33]

Epilogue: The July Crisis↑

On 28 June in Sarajevo, Bosnia, Gavrilo Princip (1894-1918), a Bosnian Serb trained in Belgrade by the Black Hand, assassinated the Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophie, Archduchess of Austria (1868–1914). By 3 July, Vienna had resolved to punish Serbia. By 6 July Berchtold had gotten assurances of German support from Wilhelm and Bethmann Hollweg, given in the hope of a quick Habsburg military effort. Then came delay. It took until 14 July to convince Tisza to agree to an ultimatum to Serbia. Things were further delayed because Habsburg troops were scattered across the monarchy on harvest leave, which ended about the time the official French state visit to Russia ended on 23 July. The forty-eight-hour ultimatum, carefully drafted so that Serbia could not accept all of its demands, was delivered the same day. Two days later the Habsburg minister declared the Serbian response inadequate. On 24 July Russia started preparatory steps for mobilization. On 28 July Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia and shots were exchanged that night. On 30 July Russia mobilized and the other great powers were soon drawn into the fray. By 5 August the Triple Entente and Austria-Hungary and Germany were at war. For the moment the Italians remained out. On 23 August Japan declared war on Germany and the Ottoman Empire reached a secret agreement with Berlin and Vienna. Woodrow Wilson proclaimed that the Americans would observe “strict neutrality.” War soon also spread to Africa. Imperialism, the arms race, balance of power politics, honor, and strong personalities: all brought the First World War.[34]

Samuel R. Williamson, Jr., The University of the South

Section Editors: Annika Mombauer; William Mulligan

Notes

- ↑ Afflerbach, Holger/Stevenson, David (eds.): An Improbable War? The Outbreak of World War I and European Political Culture before 1914, New York 2007; Angelow, Jürgen: Der Weg in die Urkatastrophe. Der Zerfall des alten Europa 1900-1914, Berlin 2010.

- ↑ Mulligan, William: The Origins of the First World War, Cambridge, UK 2010, pp. 1-91.

- ↑ Williamson, Samuel: The Politics of Grand Strategy. Britain and France Prepare for War, 1904-1914, Cambridge, MA 1969, pp. 1–29.

- ↑ Steiner, Zara / Neilson, Keith: Britain and the Origins of the First World War, New York 2003; Wilson, Keith: The Policy of Entente. Essays on the Determinants of British Foreign Policy, 1904-1914, Cambridge, UK 1985.

- ↑ Clark, Christopher: The Sleepwalkers. How Europe Went to War in 1914, London 2012, pp. 124–167.

- ↑ Steiner / Neilson, Britain and the Origins 2003, pp. 84–99.

- ↑ Clark, Sleepwalkers 2012, pp. 141–159.

- ↑ Canis, Konrad: Der Weg in den Abgrund. Deutsche Aussenpolitik 1902-1914, Paderborn, Germany 2011, pp. 117–189; Röhl, John: Wilhelm II. Der Weg in den Abgrund 1900-1941, Munich 2008, pp. 368–392.

- ↑ Williamson, Politics of Grand Strategy 1969, pp. 31–88.

- ↑ Mombauer, Annika: Helmuth von Moltke and the Origins of the First World War. Cambridge, UK 2001, pp. 42–105.

- ↑ Otte, Thomas: The Foreign Office Mind. The Making of British Foreign Policy, 1865-1914, Cambridge, UK 2011; Rose, Andreas: Zwischen Empire und Kontinent. Britische Aussenpolitik vor dem Ersten Weltkrieg, Munich 2011, pp. 347–590.

- ↑ For this and succeeding paragraphs: Clark, Sleepwalkers 2012, pp. 185–190; Williamson, Samuel: Austria-Hungary and the Origins of the First World War. New York 1991, pp. 58–81; Kronenbitter, Günther: “Krieg im Frieden.” Die Führung der k.u.k. Armee und die Grossmachtpolitik Österreichs-Ungarns 1906-1914, Munich 2003, pp. 317–367.

- ↑ Williamson, Austria-Hungary 1991, pp. 66-72, for this paragraph and the next two.

- ↑ Clark, Sleepwalkers 2012, pp. 37–47.

- ↑ Otte, Foreign Office 2011, pp. 334–354; Röhl, Wilhelm 2008, pp. 818–842.

- ↑ Clark, Sleepwalkers, 2012 pp. 194–196.

- ↑ Williamson, Politics 1969, pp. 167–204.

- ↑ Doughty, Robert: France, in: Hamilton, Richard/Herwig, Holger (eds.): War Planning 1914. Cambridge, UK 2010, pp. 143–174.

- ↑ Gooch, John: ‘The moment to act has arrived.’ Italy’s Libyan War 1911-1912, in: Dennis, Peter / Grey, Jeffrey (eds.): 1911 Preliminary Moves. Canberra 2011, pp. 184–209.

- ↑ Clark, Sleepwalkers 2012, pp. 249–266.

- ↑ Stevenson, David: Armaments and the Coming of the War. Europe, 1904-1914, Oxford 1996, pp. 231–328.

- ↑ Clark, Sleepwalkers 2012, pp. 319–322; Canis, Der Weg 2011, pp. 457–479; Röhl, Wilhelm 2008, pp. 888–925.

- ↑ Clark, Sleepwalkers 2012, pp. 293–313; Keiger, John: Raymond Poincaré. Cambridge, UK 1997, pp. 130–163.

- ↑ Williamson, Politics 1969, pp. 264–299.

- ↑ Schmidt, Stefan: Frankreichs Aussenpolitik in der Julikrise 1914. Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte des Ausbruchs des Ersten Weltkriegs, Munich 2009, pp. 105–288.

- ↑ Williamson, Austria-Hungary 1991, pp. 121–163.

- ↑ Clark, Sleepwalkers 2012, pp. 326–334; Canis, Der Weg 2011, pp. 481–519.

- ↑ Clark, Sleepwalkers 2012, pp. 334–358; McMeekin, Sean: The Russian Origins of the First World War. Cambridge, MA 2011, pp. 1–40; Menning, Bruce: War Planning and Initial Operations in the Russian Context, in: Hamilton / Herwig, War Planning 2010, pp. 80–142.

- ↑ Clark, Sleepwalkers 2012, pp. 42–47.

- ↑ Clark, Sleepwalkers 2012, pp. 349–358.

- ↑ Mulligan, Origins 2010, pp. 89–91; Canis, Der Weg 2011, pp. 611–655.

- ↑ Mulligan, Origins 2010, pp. 125–132; Hoffmann, Dieter: Der Sprung ins Dunkle. Oder wie der 1.Weltkrieg entfesselt wurde, Leipzig 2010.

- ↑ Williamson, Samuel: Leopold Count Berchtold. The Man Who Could Have Prevented the Great War, in: Bischof, Günter / Plasser, Fritz / Berger, Peter (eds.): From Empire to Republic. Post-World War I Austria, Innsbruck 2010, pp. 24–51.

- ↑ Clark, Sleepwalkers 2012, pp. 367–562; Mulligan, Origins 2010, pp. 208–235; Strachan, Hew: The First World War. The Outbreak of the First World War, Oxford 2004.

Selected Bibliography

- Afflerbach, Holger / Stevenson, D. (eds.): An improbable war? The outbreak of World War I and European political culture before 1914, New York 2007: Berghahn Books.

- Angelow, Jürgen: Der Weg in die Urkatastrophe. Der Zerfall des alten Europa 1900-1914, Berlin 2010: be.bra verlag.

- Canis, Konrad: Der Weg in den Abgrund. Deutsche Aussenpolitik 1902-1914, Paderborn 2011: Schöningh.

- Clark, Christopher M.: The sleepwalkers. How Europe went to war in 1914, New York 2013: Harper.

- Doughty, Robert: France, in: Hamilton, Richard F. / Herwig, Holger H. (eds.): War planning 1914, Cambridge; New York 2010: Cambridge University Press, pp. 143-174.

- Gooch, John: 'The moment to act has arrived'. Italy’s Libyan War 1911-1912, in: Dennis, Peter / Grey, Jeffrey (eds.): 1911. Preliminary moves. The 2011 chief of army history conference, Newport, Australia 2012: Big Sky Publishing, pp. 184-209.

- Kronenbitter, Günther: 'Krieg im Frieden'. Die Führung der k.u.k. Armee und die Großmachtpolitik Österreich-Ungarns 1906-1914, Munich 2003: Oldenbourg.

- McMeekin, Sean: The Russian origins of the First World War, Cambridge; New York 2011: Harvard University Press.

- Menning, Bruce: War planning and initial operations in the Russian context, in: Hamilton, Richard F. / Herwig, Holger H. (eds.): War planning 1914, Cambridge; New York 2010: Cambridge University Press, pp. 80-142.

- Mombauer, Annika: Helmuth von Moltke and the origins of the First World War, Cambridge; New York 2001: Cambridge University Press.

- Mombauer, Annika: Die Julikrise. Europas Weg in den Ersten Weltkrieg, Munich 2014: C.H. Beck.

- Mombauer, Annika (ed.): The origins of the First World War. Diplomatic and military documents, Manchester; New York 2013: Manchester University Press.

- Mulligan, William: The origins of the First World War, Cambridge 2010: Cambridge University Press.

- Otte, Thomas: The foreign office mind. The making of British foreign policy, 1865-1914, Cambridge; New York 2011: Cambridge University Press.

- Röhl, John C. G.: Wilhelm II. Der Weg in den Abgrund, 1900-1941, Munich 2009: Beck.

- Rose, Andreas: Zwischen Empire und Kontinent. Britische Außenpolitik vor dem Ersten Weltkrieg, Munich 2011: Oldenbourg.

- Schmidt, Stefan: Frankreichs Außenpolitik in der Julikrise 1914. Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte des Ausbruchs des Ersten Weltkrieges, Pariser Historische Studien 90, Munich 2009: Oldenbourg Verlag.

- Steiner, Zara Shakow / Neilson, Keith: Britain and the origins of the First World War, London 2003: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Stevenson, David: Armaments and the coming of war. Europe, 1904-1914, Oxford; New York 1996: Clarendon Press; Oxford University Press.

- Williamson, Jr., Samuel R.: Leopold Count Berchtold. The man who could have prevented the Great War, in: Bischof, Günter / Plasser, Fritz / Berger, Peter (eds.): From empire to republic. Post-World War I Austria, New Orleans et al. 2012: UNO Press; Innsbruck University Press, pp. 24-51.

- Williamson, Jr., Samuel R.: Austria-Hungary and the origins of the First World War, New York 1991: St. Martin's Press.

- Williamson, Jr., Samuel R.: The politics of grand strategy. Britain and France prepare for war, 1904-1914, Cambridge 1969: Harvard University Press.