Introduction↑

As nationalist movements gained momentum in Europe during the 19th and 20th centuries, minorities within the Ottoman Empire such as the Greeks (1821-1832), Bulgarians (1876), and Serbians (1804-1817) revolted against the regime seeking various levels of autonomy and independence. Facing internal dissent and increasing external pressures, Ottoman government began to implement European-inspired reforms during the 19th century, commonly referred to as the Tanzimat era. The aim was to modernize the state and regain its declining control over its subjects. The reforms included establishing an Ottoman constitution and parliament during the First Constitutional Era (1876-1878), which were dissolved in 1879 but reinstated in 1908. The reform period brought with it a series of profound social and political transformations, including the hope of inclusivity for minorities and representational politics. A notable feature was the government’s firm commitment to pursuing a policy of centralization, which involved enforcing the use of Ottoman Turkish throughout the empire in post-elementary education and state institutions. Measures like this contributed in part to a growing sense of marginalization and oppression among segments of the empire’s Arab population.

As apprehension about the empire’s position, identity, and future grew, political articulations of an Arab identity as distinct from the Turkish governing entity began to emerge. In 1913, the First Arab Congress convened in Paris to discuss the rights of Arabs under Ottoman rule. Attended by twenty-five official delegates from various Arab nationalist societies, as well as several unofficial delegates, the Congress discussed greater local Arab administrative control, demanded that Arabic become the official language of the Arab regions, and called for the right of the empire’s Arab soldiers to perform their military service locally. In addition, suppression of Arab nationalist activities during the war, such as the members of Arabist societies in Syria, further reinforced the image of Ottomans as oppressors. Despite this, Arab nationalism as a political movement was not fully formulated until after World War I, and the majority of Arab Ottoman subjects still primarily identified with their family, tribe, or religion rather than their “Arabness.” Throughout the challenging events of the war and the end of the empire, most Arabs generally did not question the legitimacy of Ottoman rule over Muslim lands with the sultan as the caliph of the Muslim ummah.

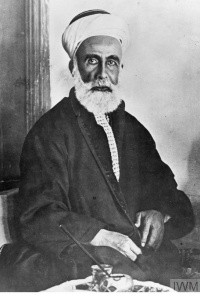

Against this backdrop, the leaders of the Arab Revolt launched their rebellion in the name of Arab and Muslim unity, freedom, and independence. The events, however, were rooted in a collaborative pursuit of self-interests by the British fighting the Central Powers on the one hand, and Sharif Husayn bin ‘Ali, King of Hejaz (c. 1853-1931), the Ottoman-appointed emir of Mecca on the other. Husayn envisioned an Arab kingdom over which he would rule independent of Ottoman control. After the 1909 overthrow of Abdülhamid II, Sultan of the Turks (1842-1918), Husayn’s relationship with the Ottoman government under the leadership of the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) had begun to decline. He was dissatisfied with the restrictiveness of the state’s increasingly centralizing initiatives which would undermine the autonomy of his position. The CUP, for its part, harbored suspicions over his refusal to publicly endorse the Ottoman sultan’s declaration of jihad, or holy war, against the Allied powers following the empire’s decision to join World War I on the side of the Central Powers. Evidence of a Unionist plot to depose him further alienated Husayn. In response, he instructed his son Faysal I, King of Iraq (1885-1933) to negotiate with the leaders of two Arab nationalist secret societies in Damascus, al-Fatat and al-‘Ahd, producing the Damascus Protocol (1915) which affirmed these societies’ support of a revolt led by Sharif Husayn for an independent Arab territory recognized by Britain.

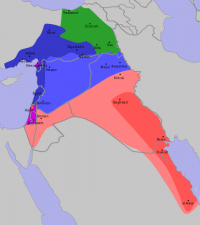

Britain had been reluctant about to the idea of a revolt when approached prior to the war by Husayn’s older son, ‘Abdullah ibn Husayn, King of Jordan (1882-1951). Now fully embroiled in the war, however, the British government quickly changed its stance. British High Commissioner in Egypt Sir Arthur Henry McMahon (1862-1949) corresponded with Sharif Husayn about the matter from July 1915 through January 1916, promising, albeit in intentionally vague terms, British financial and military support of a revolt and the recognition of an independent Arab state after the war. The Allies hoped an Arab revolt would divert enemy resources and disrupt an alarming pattern of Ottoman victories, such as their triumph at the Battle of Gallipoli (February 1915-January 1916) and their successful siege of British troops in the city of Kut (December 1915-April 1916). For the British, Husayn proved a suitable figurehead for rallying the Arabs. Not only did he have the backing of the Arab nationalist secret societies, but also the credentials of head of the Hashemites, a dynasty tracing its lineage back to the Prophet Muhammad (c. 570-632), and therefore regarded as the legitimate rulers of the holy cities of Mecca and Medina.[1] Meanwhile, Britain also entered into negotiations with both French and Zionist leadership culminating in the signing of two agreements that would conflict with the terms of the Husayn-McMahon correspondence: the secret Sykes-Picot Agreement (1916), which allocated British and French post-war spheres of control and influence in the region, and the Balfour Declaration (1917), which promised British support in establishing a homeland for Jews in Palestine.

Course of the Revolt↑

On 5 June 1916 at a camp in Medina of around 1,500 recruits, Husayn’s sons ‘Ali bin Husayn (1879-1935) and Faysal declared in the Sharif’s name their independence from Turkish rule. They launched an attack on Ottoman troops at Medina and sabotaged the railway track connecting the city to the north, hindering the delivery of Ottoman reinforcements. The revolt was then officially announced on 10 June 1916 in Mecca with Husayn’s symbolic rifle shot, followed by attacks on the city’s Ottoman units and its water supply. Shortly after, a battery from Egypt was dispatched by Britain to the Hejaz to help bolster the Arabs and capture Mecca in July 1916. The Ottoman garrison at Medina, which had resisted the initial Arab attack, continued to put up a strong defense under Lieutenant General Ömer Fahreddin Pasha (1868-1948), holding out against rebel forces' siege of the city and refusing to surrender until after the war in January 1919.

The port of Jiddah fell soon after Mecca, as British navy cruisers and seaplanes assisted Arab rebels by bombing Ottoman troops there. Jiddah’s surrender was a crucial political and military victory, opening up access to food and material supplies. The Arabs under ‘Abdullah’s command also besieged Ta’if in conjunction with the Egyptian battery and finally took the city in September 1916. With the assistance of the British Royal Navy, Arab forces captured various other Red Sea port cities. Hundreds of Ottoman Arab subjects from these cities were taken as prisoners of war and made to fight as reinforcements for the Arab troops. Britain also sent over Muslim soldiers from its territories in North Africa to fight with the Arab forces against the Ottomans.

Further reinforcements came in the form of Allied troops from Egypt and India, as well as explosives, rifles, machine guns, artillery, armored cars, and Britain’s Imperial Camel Corps. Additionally, British and French military officials, including the well-known T. E. Lawrence (1888–1935), worked closely with the Hashemites on intelligence and strategy coordination. Frequent Arab raids on the Hejaz Railway disrupted supply lines and tied up Ottoman forces at the cost of defending other major fronts, such as Iraq and Palestine. Although the rebel troops at the beginning of the revolt consisted mainly of tribal guerilla forces, a regular Arab army that fought full-time was formed by the Allies in late 1916. It was known as the Sharifian Army, and consisted of many notable Ottoman Arab prisoners of war captured by the British, such as Nuri al-Sa‘id (1888-1958) and ‘Aziz ‘Ali al-Misri (1879-1965).

In 1917, Lawrence and Faysal coordinated a victorious attack on the port of ‘Aqabah, although they did encounter strong and sometimes successful resistance from residents in the region, who remained firmly on the side of the Ottomans.[2] The Arab rebels also aided British General Edmund Allenby’s (1861-1936) attacks on the Ottoman defensive line in Gaza-Beersheba and the Yarmuk River valley, which led to the British capture of Jerusalem in December 1917. Arab and Allied offensives continued to advance throughout 1918, neutralizing Ottoman positions and causing their defenses to steadily retreat and surrender. Rebel forces finally captured Damascus at the beginning of October 1918, and on 30 October 1918, the Armistice of Mudros was signed, officially ending hostilities between the Ottoman Empire and the Allies. The Syrian National Congress (March 1920) proclaimed Faysal the king of Syria, a position that was not to last as post-war negotiations proceeded.

Aftermath↑

The 1919 Paris Peace Conference negotiations resulted in a partitioning of Ottoman territories among the war’s victors, mostly based on British and French colonial interests, as they were outlined in Sykes-Picot. The newly-established League of Nations granted Britain and France control in the form of mandates. Contrary to the terms discussed by Husayn and McMahon, Greater Syria was not given to the Arabs. Instead, it became a French mandate, while Britain was given mandates for Mesopotamia (Iraq) and Palestine. In the end, the only independent Arab state resulting from the post-war negotiations was limited to the Kingdom of Hejaz, over which Husayn was internationally recognized as king. However, Britain continued to influence the political landscape there as well, leveraging incentives like weaponry and subsidies it sent to Husayn and his rival Ibn Sa‘ud (1875-1953), the ruler of Najd and another British protégé.

France battled Faysal’s Arab nationalist forces in the Franco-Syrian War (1920) to officially establish full French control over Syria. Faysal was deposed, and French colonial rule lasted until Syrian independence in the mid-1940s. Britain opened up Palestine to increased Jewish migration as per the Balfour agreement, contributing to increased Arab outrage and distrust.[3] In 1920, Iraqis from different religious and tribal groups revolted together against British occupation of their lands. Britain quickly defeated the revolt, then opted for a more indirect form of control in the region, installing Faysal and ‘Abdullah as loyal kings in Iraq and Transjordan respectively. In 1925, the Hashemites were ousted from their position as rulers of the Hejaz by their neighboring rivals, the Sa‘ud dynasty, which would then go on to establish modern-day Saudi Arabia. The Hashemite monarchy in Iraq was eventually overthrown by an Iraqi army coup in 1958, leaving contemporary Jordan as the final vestige of Hashemite rule in the region today.

The post-war settlement created deep and long-lasting mistrust among the region’s peoples, as it became clear that one colonial rule was simply being replaced by another. New states were carved out of the remains of the Ottoman Empire by European men drawing arbitrary lines on a geographical map – divisions that served the imperial interests of the French and British, with little regard to the ethnic, political, or religious affiliations of the inhabitants of these regions. Heads of state were installed as part of the British agreement with the Hashemites, often to the disapproval of the people over whom they were to rule, and in many instances, this European control sparked bloody rebellions across the region. Colonial violence was heavily employed both militarily and through initiatives such as urban planning and engineering to suppress resistance and dominate the social order.[4] The fragmentations, artificial borders, imposed leadership, and brutality of the post-war settlement only served to compound the subsequent process of nation-building with instability.[5]

Legacy↑

The Arab Revolt came to serve as a key event referenced repeatedly in Arab nationalist rhetoric after World War I. The Sharifians used the revolt as the prime symbol for legitimizing Faysal’s position when he was proclaimed king of Greater Syria in 1920. Although not very well-known locally, Faysal based his right to rule Damascus on the Sharifians’ brave success at preserving a nation for the Arabs while the rest of the Ottoman Empire fell into shambles. Furthermore, Faysal positioned the revolt as indispensable to the broader Arab revolutionary movement’s narrative, responsible for translating what had until then been merely ideas about Arabism, as first conceived by the Syrians prior to the war, into real action.[6] George Antonius (1891-1942), a prominent early scholar of the movement, furthered this notion that the revolt was a revolutionary struggle for emancipation inspired by a process of the Arabs awakening to their unique identity.

More recent scholarship on the revolt and the origins of Arab nationalism generally agree there is little historic evidence that Husayn was a nationalist leader motivated to rise up for the sake of the Arab nation. These works maintain that the revolt was less about true popular aspirations and more the result of Sharifian dynastic ambitions converging with British strategic interests. Nonetheless, the Arab Revolt has remained what Peter Wien called “the founding myth of Arab nationalism,”[7] representing the Arab revolutionary spirit and the movement’s ideals of heroism and sacrifice. The events of the revolt are still glorified in official history textbooks taught in schools across much of the Arab world today. The revolt’s legend lives on through poems like the works of Fu’ad al-Khatib (1882-1957) which continue to be recited, broadcast on television, and posted to online video websites; as well as through stories and state-sponsored commemorations of the revolt’s heroes, such as the statue of Yusuf Al-‘Azma (1884-1920) in Damascus.[8] Many of the modern Arab states’ flags are inspired by the flag the Arabs used during the revolt, and a glance at the Kingdom of Jordan’s Great Arab Revolt Centennial website shows the extent to which memory of the rebellion continues to be mobilized by Arab nationalist rhetoric.[9] In contrast to how the Arab Revolt was celebrated by many Arab nationalists, Turkish rhetoric has historically positioned the revolt as a major Arab betrayal that contributed to the overall Turkish defeat in the war.[10] This betrayal would become a point of significant tension in the Arab-Turkish relationship for decades thereafter.

Conclusion↑

Arab nationalism continued to develop into a full-fledged political movement after World War I, taking on new forms with changing times and local contexts. Its development was largely due to the legacy of the mandate system imposed by Britain and France in the war’s wake. In the face of this unjust and often violent neo-colonialism, Arab nationalism became one of several ideological visions around which Arabs mobilized to pursue a just and representative political system that would protect citizens’ rights.[11] The Arab nationalist movement’s rhetoric of anti-imperialism and resistance to Western intervention in Arab affairs was rigorously spread to the masses through education and the press. Although Arab nationalism eventually fell into decline,[12] the legacy of the Arab Revolt with its impact on the outcomes of World War I, and the ensuing instability caused by the European-created political order in the region, continues to affect the Middle East today.

Alia El Bakri, Independent Scholar

Section Editors: Melanie Schulze-Tanielian; Yiğit Akin

Notes

- ↑ The Hashemites’ lineage is still referenced today in support of Hashemite rule in the modern-day Kingdom of Jordan. Jordan is the only remaining state in the region governed by the Hashemites, currently ruled by ‘Abdullah ibn Husayn’s great-grandson, King ‘Abdullah the Second. A diagram illustrating the royal family’s line of descent from Prophet Muhammad can be found posted on the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan’s Ministry of Education website, on a page titled “National Awakening, issued by” Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan Ministry of Education, online: (http://www.moe.gov.jo/Directorates/DirectoratesSectionDetails.aspx?DirectoratesSectionDetailsID=271&DirectoratesID=6 (retrieved: 9.5.2017). Accompanying the diagram are Quranic verses and a Prophetic saying enjoining believers to love and revere the descendants of the Prophet’s family.

- ↑ Eugene Rogan provides an account of the Karak locals joining together to fight the Hashemite-led forces. The group of 500 men killed nine rebel fighters and captured two of their horses. See Rogan, Eugene: The Arabs. A History, New York 2011 p. 152.

- ↑ The Balfour Declaration was a crucial development in creating one of the most enduring sources of conflict in the region. Making British support of a Jewish national homeland in Palestine official, it gave international recognition to the Zionist movement and paved the way for the establishment of the state of Israel. For more details, see Said, Edward: The Question of Palestine, New York 1981.

- ↑ Neep, Daniel: Occupying Syria Under the French Mandate. Insurgency, Space and State Formation, Cambridge 2012, p. 131.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 37.

- ↑ See Gelvin, James L.: Divided Loyalties. Nationalism and Mass Politics in Syria at the Close of Empire, Berkeley 1998, pp. 171-172.

- ↑ Wien, Peter: Arab Nationalism. The Politics of History and Culture in the Modern Middle East, New York 2017, p. 31

- ↑ Provence, Michael: The Last Ottoman Generation and the Making of the Modern Middle East. New York 2017 p. 34.

- ↑ See especially sections titled “Revolution Heroes,” “Great Arab Revolution Flag,” and “Values List:”, issued by The Royal Heritage Directorate, online: http://arabrevolt.jo/en/ (retrieved: 9.5.2017).

- ↑ See Küçükcan, Talip: Arab Image in Turkey, SETA Research Report No.1, Ankara 2010, p. 8.

- ↑ Elizabeth Thompson provides a comprehensive study of how this pursuit was part of a broader tradition of indigenous Middle Eastern efforts to conceptualize and establish justice in emerging state institutions. See Thomspon, Elizabeth: Justice Interrupted. The Struggle for Constitutional Government in the Middle East, Cambridge 2013.

- ↑ Arab nationalism peaked in strength under Egyptian president Jamāl ‘Abd al-Nāṣer (1918-1970) in the 1950s and 1960s with his land reforms, nationalization projects, and his role in the formation of the United Arab Republic with Syria. The movement fell into decline for a variety of reasons but was dealt a particularly heavy blow by the inability of the Arab coalition to successfully defend Palestine against Israeli territorial expansion in 1967.

Selected Bibliography

- Allawi, Ali A.: Faisal I of Iraq, New Haven 2014: Yale University Press.

- Anderson, Scott: Lawrence in Arabia. War, deceit, imperial folly and the making of the modern Middle East, London 2014: Atlantic Books.

- Antonius, George: The Arab awaking. The story of the Arab national movement, London 1938: H. Hamilton.

- Choueiri, Youssef M.: Arab nationalism. A history. Nation and state in the Arab world, Oxford; Malden 2000: Blackwell.

- Cleveland, William L. / Bunton, Martin P.: A history of the modern Middle East, Boulder 2016: Westview Press.

- Dawisha, Adeed: Arab nationalism in the twentieth century. From triumph to despair, Princeton 2003: Princeton University Press.

- Gelvin, James L.: Divided loyalties. Nationalism and mass politics in Syria at the close of empire, Berkeley 1998: University of California Press.

- Karsh, Efraim / Karsh, Inari: Empires of the sand. The struggle for mastery in the Middle East, 1789-1923, Cambridge 1999: Harvard University Press.

- Kayalı, Hasan: Arabs and Young Turks. Ottomanism, Arabism, and Islamism in the Ottoman Empire, 1908-1918, Berkeley 1997: University of California Press.

- Kedourie, Elie: In the Anglo-Arab labyrinth. The McMahon-Husayn correspondence and its interpretations, 1914-1939, Cambridge 1976: Cambridge University Press.

- Khalidi, Rashid (ed.): The origins of Arab nationalism, New York 1991: Columbia University Press.

- Lawrence, T. E.: Seven pillars of wisdom. A triumph, London 1935: J. Cape.

- Mohs, Polly A.: Military intelligence and the Arab revolt. The first modern intelligence war, London; New York 2008: Routledge.

- Neep, Daniel: Occupying Syria under the French mandate. Insurgency, space and state formation, Cambridge 2012: Cambridge University Press.

- Paris, Timothy J.: Britain, the Hashemites and Arab rule, 1920-1925. The Sherifian solution, London 2003: Frank Cass.

- Provence, Michael: The last Ottoman generation and the making of the modern Middle East, Cambridge 2017: Cambridge University Press.

- Rogan, Eugene L.: The Arabs. A history, New York 2011: Basic Books.

- Teitelbaum, Joshua: The rise and fall of the Hashimite kingdom of Arabia, New York 2001: New York University Press.

- Wien, Peter: Arab nationalism. The politics of history and culture in the modern Middle East, London; New York 2017: Routledge.