Overview↑

The Husayn-McMahon Correspondence refers to the ten letters exchanged between Husayn ibn Ali, King of Hejaz (c.1853-1931) Sharif of Mecca and the newly appointed British High Commissioner in Egypt, Sir Henry McMahon (1862-1949), from July 1915 to March 1916. The correspondence explored the terms of an Anglo-Arab alliance and Britain’s material support for a Hashemite-led Arab uprising against the Ottoman Empire. It also encompassed protracted negotiations over the extent and contours of the independent Arab State that the Hashemites hoped to rule after the conclusion of hostilities. Aware that Great Britain was concurrently engaged in negotiations with its French allies over the post-war disposition of the territories of the Ottoman Empire, McMahon deliberately injected a degree of obfuscation into his answers to the Sharif. For his part, Husayn did not dwell on McMahon’s evasions, preferring to cement an alliance that promised him immediate material support as well as the possibility of future political gain. Once the dream of an independent Arab State receded after the end of the war, the ambiguities of the Husayn-McMahon exchange fuelled accusations of British perfidy, while leaving the Hashemites open to the accusation that they had sacrificed Arab national interests on the altar of dynastic ambition.

Negotiating an Anglo-Arab Alliance during WWI↑

The Husayn-McMahon correspondence built on pre-war Hashemite contacts with the British in Egypt that sought to find common ground for an alliance against the Ottoman Empire. The negotiations were undertaken when British fortunes in the Middle Eastern theatre were at a low. In the summer of 1915, British and Commonwealth forces were pinned down by Ottoman and German forces in Gallipoli, and by December 1915, the British Indian forces in Mesopotamia were besieged by Ottoman forces in Kut al-‘Amara. At the same time, a deteriorating economic situation in Egypt fed the High Commissioner’s fears that the call to Jihad issued by the Sultan-Caliph upon the Ottomans’ entry into the war in September 1914 would find a popular response.

Faced with deteriorating fortunes on the battlefield and convinced that the religious prestige of the Hashemites could be used to counter the Ottoman call to Jihad, Whitehall authorized its proconsuls in Cairo to respond to the overtures of the Meccan Sharifs. This brought relief to Husayn, who was threatened by the alliances forged by Britain with such Arabian rivals as the Idrisis in ‘Asir and the Sa‘udis in Najd. An alliance with Britain also promised release from the hardships resulting from the war-induced collapse of the pilgrim trade and the food shortages caused by the British naval blockade of the Red Sea ports. These considerations ensured that demands for economic support formed an important – if still too often neglected – subtext of the correspondence. In his exchanges with McMahon, Husayn raised a host of material demands, ranging from the freeing of the Egyptian waqfs (endowments) assigned to provision the Hejaz to detailed lists of the supplies needed to foment an armed uprising against the Ottomans.

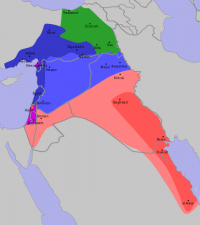

The main texts of the correspondence, however, dealt with the sovereignty and territorial basis of a post-war Arab state. Husayn wrapped himself in the mantle of leadership of a wider Arab National Movement, and demanded that Britain recognize him as the king of an independent Arab state that stretched from southern Arabia (excluding the British base in Aden) to the Taurus Mountains (initially including Arab Cilicia only partially). Even the Arabists among the British intelligence community in Cairo were inclined to treat these demands as a gambit that greatly overestimated the Sharif’s actual weight in Arabian affairs, and exaggerated his influence on the politics of the Fertile Crescent. However, more credence was given to Husayn’s claims to represent the Arab Nationalists of Syria and Iraq by the information on the Arab Movement supplied by Lieutenant Muhammad al-Faruqi (1891-1921), who crossed the battle lines at Gallipoli just as Husayn’s initial response to McMahon’s letters arrived in Cairo in the autumn of 1915. Keen to ensure the Sharif’s support, the British proceeded to promise more than was compatible with the claims to “La Syrie Integrale” pursued by their French allies, or with their own ambitions in Palestine and Mesopotamia, while cloaking their commitments in such ambiguity as would allow credible obfuscation once the war was over.

The contradictions that resulted from this strategy appear most clearly in the famous letter dispatched to Husayn on 25 October 1915. McMahon seems to have deliberately chosen a vague formulation and changed the punctuation of key phrases in order to give Husayn the impression that Britain was free to recognize Arab independence within proscribed limits. Under pressure from the Foreign Office, McMahon offered an amorphous agreement with the Sharif that ceded most of his territorial demands while excluding what is now southern Iraq and parts of coastal Syria. The calculated nature of the undertaking is made clear by McMahon’s confusing assertion that the two cities of Mersin and Alexandretta, as well as those parts of Syria west of Damascus, Homs, Hama, and Aleppo were not Arab and should be excluded from the Arab state. Crucially for later accusations of Husayn’s cupidity, and for his own sense of betrayal by the British, according to any reasonable interpretation of the geography of Arabic-speaking coastal Syria, the excluded areas could not have included either Palestine or Lebanon, both of which were the subject of competing claims by the Zionist Movement and the French.

War's Aftermath. The Anglo-Arab Labyrinth↑

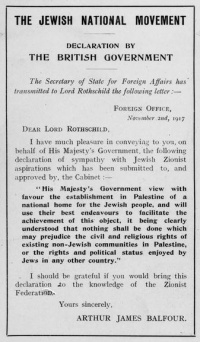

The commitments made by McMahon were one of three mutually incompatible promises made by Britain regarding the post-war disposition of the territories of the Middle East. The other two were the Sykes-Picot Agreement on the division of the Fertile Crescent and the promise of a Jewish homeland in Palestine made in the Balfour Declaration of November 1917. Once Arab hopes of national fulfillment began to recede with the division of Greater Syria and the acceleration of Jewish migration to Palestine, the contradictory nature of the three undertakings sparked bitter controversy. The ambiguities of the Husayn-McMahon exchanges ensured that they were drawn into labyrinthine historical debates over British perfidy and Hashemite ambition that only intensified with the release of the relevant historical documents from the late 1930s onwards. Most of the contributors to these controversies – notably the followers of Elie Kedourie (1926-1992) – rely predominantly on British or European sources. George Antonius’ (1891-1942) Arab Awakening remains to this day the only credible academic source in a European language in which the Hashemites’ own version of the negotiations – drawn from its author’s conversations with leading members of the dynasty – are given a sympathetic scholarly airing.

Tariq Tell, American University of Beirut

Section Editor: Abdul Rahim Abu-Husayn

Selected Bibliography

- Barr, James: A line in the sand. Britain, France and the struggle that shaped the Middle East, London 2011: Simon & Schuster.

- Fromkin, David: A peace to end all peace. Creating the modern Middle East, 1914-1922, London 1989: Penguin.

- Hurewitz, J. C. (ed.): The Hussein-McMahon correspondence 14 July 1915-10 March 1916, in: Hurewitz, J. C. (ed.): The Middle East and North Africa in world politics. A documentary record, New Haven 1979: Yale University Press.

- Kedourie, Elie: In the Anglo-Arab labyrinth. The McMahon-Husayn correspondence and its interpretations, 1914-1939, Cambridge 1976: Cambridge University Press.

- Rogan, Eugene L.: The fall of the Ottomans. The Great War in the Middle East, New York 2015: Basic Books.