Occupation of Basra↑

Before the declaration of war between the Ottoman Empire and Great Britain, the British command had already dispatched an Indian Expeditionary Force (IEF), Sixth Indian Division, to the Gulf to secure the oil facilities of the Anglo-Persian Oil Company on the island of Abadan in the Shatt al-Arab. The aim was also to strengthen the British position in the region and, if possible, to occupy Basra.

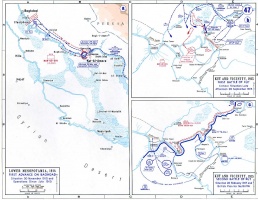

The day after the outbreak of war between the two empires, on 6 November 1914, the IEF began to take action, occupying first Fao and then Abadan. The Ottoman command was unprepared, short on manpower, and experiencing problems with its local tribal forces. As a result, the IEF advance in the Basra region along the Tigris valley was easy and quick; the city of Basra fell on 23 November 1914 and Qurna on 9 December 1914.

The Battle of Shu’aybah↑

The Ottoman command appointed Süleymân Askerî Bey (1884-1915), a leading officer of the Teşkilat-ı Mahsusa (the Special Organization) as commander of Basra in January 1915 and charged him with retaking the city. In April 1915, he attacked the IEF around Qurna with a mixed force of 4,000 regulars and approximately 15,000 Arab tribal levies from southern Iraq. At the battle of Shu'aybah (on 12 April 1915), the tribal levies were routed and the Ottoman forces faced a humiliating defeat. Askerî took his life in despair.

Tribal uprisings followed, starting in May and continuing throughout the summer of 1915. The towns and villages of the Middle Euphrates rose in rebellions in southern Iraq, including the Shiite sacred towns of Najaf and Karbala. In the meantime, the IEF advance continued along both the Tigris and the Euphrates, through Ammara and Nasiriyya respectively. After Shu'aybah, the Ottoman command had to withdraw and regroup to defend the roads towards Baghdad instead of trying to regain Basra. The Ottoman forces were unsuccessful in the face of the IEF advance. By August 1915, the IEF completed the occupation of the entire province of Basra.

This advance gradually began to create logistical problems for the IEF; as they were forced to stretch their lines of supply and communications ever further. The pre-1914 reforms to the Indian Army, largely the work of Horatio Herbert Kitchener (1850-1916), were the root cause of many of the logistic and administrative problems that the IEF faced as it advanced deeper into Mesopotamia.

The Impact of Gallipoli Campaign↑

At this time, the developments on the Gallipoli front began to determine the developments on the Mesopotamian Front, for both the Ottomans and the British. There was fear and concern in London over the wider ramifications in the Muslim world of their prospective defeat at Gallipoli, which was apparent by the autumn of 1915. In order to regain prestige, especially in (British) India and other Muslim colonies, British decision makers began to plan new offensives elsewhere in the Middle East. One of these was the IEF’s advance on Baghdad.

Meanwhile, victory at Gallipoli had allowed the Ottomans to transfer two experienced and disciplined divisions to the Mesopotamian Front, which tilted the military balance in their favor. Ottoman forces in Mesopotamia and Persia were reorganized into the Sixth Army in September 1915, and Field Marshal Colmar von der Goltz (1843-1916) was appointed commander-in-chief. Under him were two sub-commanders responsible for Iraq: Mehmed Nurettin Pasha (1873-1932) and Halil Kut Pasha (1881-1957), a cousin of Enver Pasha (1861-1924). By the end of 1915, Ottoman forces had reached a total of 25,000 soldiers, compared with 14,000 IEF soldiers. The Ottoman forces were also assisted by tribal levies under the command of Ujaymi al-Sadun (?-1960) of the Muntafiq tribal confederation.

At the same time, the Ottoman government was carrying out propaganda activities to win the support of local Arab populations, especially the Shiites of Iraq. Already in November 1914, at the request of the Ottoman authorities, almost all the leading mujtahids of Atabat had issued fatwas calling upon Muslims for jihad against the Allies. Later, in the autumn of 1915, the Ottoman government sent “the noble Banner of Ali” from Istanbul to Atabat. The mujtahids continued to support the Ottoman authorities until the end of the Mesopotamian campaign. The Ottomans also accelerated its pan-Islamic propaganda aimed at Muslim Indian soldiers serving on the Mesopotamian Front. This bore fruit as desertions and disobedience arose within the rank and file of the IEF, especially among the Pashtuns; although such incidents were limited and had little effect on the British-Indian army’s combat capability.

The Battle at Ctesiphon↑

The British forces were suffering from logistical problems and a shortage of men. After the IEF occupied Kut al-Amara at the end of September 1915, Major General Charles V. F. Townshend (1861-1924) decided to halt there to secure British control over the whole province of Basra and insisted on waiting for reinforcements. However, the IEF’s easy victories in Basra province encouraged British decision makers in London and Delhi to advance further northwards and capture Baghdad. This was partly to compensate for the great loss of prestige they had suffered on the Gallipoli front; partly an attempt at Delhi’s sub-imperial expansion in the Gulf and Mesopotamia; and partly to help Russian war effort by putting pressure on the Ottoman Empire. Despite Towshend’s position, the British general command, misreading of renewed Ottoman capabilities, authorized the advance on Baghdad. In November 1915, Townshend attacked the Ottoman forces at Selmanpak (an ancient site known as Ctesiphon), about 35 kilometres southeast of Baghdad. Ottoman forces fought a successful defensive action (22-24 November) at Selmanpak.

The Siege at Kut↑

After failing to break through the Ottoman positions at Selmanpak, Townshend began to withdraw to Kut al-Amara (25 November), a wide peninsula in a horseshoe bend of the Tigris 100 miles south of Baghdad, where he was besieged. With a force of 11,600 combatants and 3,350 non-combatants, and with rations for 60 days, the besieged army waited for relief from Basra. Ottoman forces attempted to seize Kut several times, but in the face of heavy losses instead opted to tighten the siege and cut off British reinforcement and resupply from Basra.

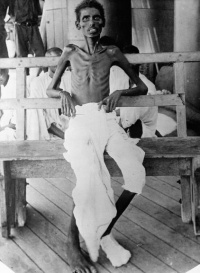

Townshend misrepresented the state of his supplies in order to force a quicker response from the forces in southern Mesopotamia and thus push for a relief early on. As a result, British and Indian troops were thrown against the Ottoman defences south of Kut before they were ready (both in training, fire support, and numbers) and as a consequence the relief efforts failed. The British made four unsuccessful attempts to free the troops besieged at Kut, and suffered over 23,000 casualties. Attempts at sending aid via airplanes and submarines also failed or were insufficient. Due to shortages of food and medicine, starvation and disease began to take their toll. The Hindu and Muslim Indian soldiers refused horsemeat on religious grounds, and as malnutrition set in, they grew weaker and fell ill.

After 147 days of siege, facing starvation and without any prospect of relief, Townshend was authorized to enter into negotiations for surrender. During negotiations, Townshend, and later Thomas Edward Lawrence (1888-1935) and Aubrey Herbert (1880-1923) of the Arab Bureau, tried to bribe the Ottoman commander Halil to allow their forces to flee; they offered first one million (and then two million) pounds, but to no avail. On 29 April 1916, Townshend, left with no other alternative, surrendered his force of 13,309 men, consisting of 277 British officers, 204 Indian officers, 2,592 British soldiers, 6,988 Indian soldiers, and 3,248 Indian support staff. On 2 May 1916, 1,306 sick or wounded soldiers were allowed to leave aboard British medical ships, together with 694 nursing and support staff to tend them.

Prisoners of War↑

Townshend was taken to Istanbul, where he was treated as befitted a man of his station. The remaining prisoners of war were sent to prison camps in different places in western and central Anatolia. Most of the rank-and-file soldiers were forced to march on foot, as the British refused to provide transport and the Ottomans were unable to do so. The prisoners of war received differential treatment according to their rank and religious affiliation, with officers and the 4,014 Muslim soldiers enjoying relatively better conditions. Of the total British-Indian rank and file, nearly 70 percent are estimated to have died in captivity or on the road. The British are estimated to have suffered some 40,000 casualties during this campaign, compared with losses on the Ottoman side of 350 officers and 10,000 soldiers from the Sixth Army.

The Importance of Kut↑

This was a great victory for the Ottomans. In Halil’s words, it was a Turkish victory “the likes of which hadn’t been seen for 200 years.” And it was as great a defeat for the British Empire. Kut ranks, alongside Yorktown (1781) and Singapore (1942), as one of the three most significant defeats of British arms. However, while Yorktown and Singapore led to major imperial/strategic consequences for the British Empire, Kut did not.

The Ottomans were not able to use the success at Kut to further their war effort at Mesopotamia. Within a year, the Ottoman gains had been reversed. The Ottoman central command redeployed many of its forces in Mesopotamia to the Iranian front; whereas the British overcame their defeat to stage a successful campaign in late 1916 and early 1917 (a more cautious and far better resourced one) that destroyed the Ottoman grip on the Baghdad and Mosul. With a newly raised and reinforced force of 150,000, General Stanley Maude (1864-1917) started a new advance in December 1916, retaking Kut al-Amara in February 1917 and entering Baghdad in March 1917.

Finally, the Arab Revolt of 1916 was also related to the consequences of Kut. After the great blows to its prestige at Gallipoli and Kut, the British government feared that Ottoman victories risked provoking pan-Islamic sentiment and revolts in India and the Arab world. In Cairo, the Arab Bureau accelerated its efforts to strike the Ottomans from the rear. This led to the Arab revolt a few months later in June 1916.

Gökhan Çetinsaya, Istanbul Şehir University

Section Editors: Abdul Rahim Abu-Husayn; Heike Liebau

Selected Bibliography

- Çifci, Erhan (ed.) / Kut, Halil: Kutü'l-amare kahramanı Halil Kut Paşa'nın hatıraları (Memories of Halil Kut Pasha), Istanbul 2015: Timaş Yayınları.

- Erickson, Edward J.: Gallipoli and the Middle East, 1914-1918. From the Dardanelles to Mesopotamia, London 2008: Amber Books.

- Gardner, Nikolas: The siege of Kut-al-Amara. At war in Mesopotamia, 1915-1916, Bloomington 2014: Indiana University Press.

- Johnson, Robert: The Great War and the Middle East. A strategic study, Oxford 2016: Oxford University Press.

- Rogan, Eugene L.: The fall of the Ottomans. The Great War in the Middle East, New York 2015: Basic Books.

- Townshend, Charles Vere Ferrers: My campaign, 2 volumes, New York 1920: J. A. McCann.