Introduction↑

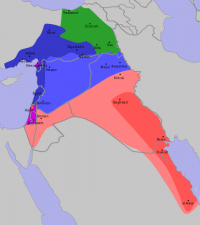

The May 1916 agreement negotiated by Sir Mark Sykes (1879-1919) and François Georges-Picot (1870-1951) painted the Fertile Crescent in shades of Red (for Great Britain’s sphere of influence) and blue (the French sphere). For many Arabs today, “Sykes-Picot” remains a byword for secret diplomacy and the ruthless realpolitik associated with colonial ambition. Yet in its original form, the map of the Fertile Crescent envisaged by “Sykes-Picot” differed markedly from the colonial system of states that emerged at St. Remo (1920) and ratified at Lausanne (1923). Mosul and Palestine (respectively French and international in the original agreement) now went to Britain, whose armies, allies, and colonial auxiliaries had done most of the fighting against the Ottomans and whose forces were in occupation of Syria and Mesopotamia at the end of the war. Recent historical work maintains that it was these territorial shifts, and the unintended consequences that they had for Anglo-French relations, that would have the greatest long-term effect on the history of the Levant.

Imperial Interests in the Fertile Crescent↑

The Sykes-Picot negotiations built on imperial strategies that predated the emergence of an Arab Movement and Hashemite contacts with the British in Egypt. A key determinant was the alliance with Tsarist Russia, which reconfigured the politics of the Eastern Question and precipitated a steady retreat from the traditional Anglo-French commitment to preserving the Ottoman Empire. Britain accepted that France had prior claims to Syria as early as 1904, when the Entente Cordiale was formed, trading its acceptance of them for French recognition of its neo-colonial domination of Egypt. For its part, France pursued a Levantine imperial sphere and a large share of the Ottoman public debt. With British support, it sought to become the leading investor in the network of railways that was to span Anatolia and the Fertile Crescent.

While Britain’s interests in the Near East had been largely satisfied by the acquisition of Egypt in 1881 and her domination of southern Iran, her “men on the spot” in Cairo and Delhi hatched more ambitious plans for an expansion of empire into Iraq and the Levant. Imperial strategists maintained that this was necessary to protect the northern approaches to the Suez Canal (and therefore the routes to India), as well as to keep control of the oil fields around Abadan (which gained greatly in strategic importance once the Royal Navy made the shift from coal to oil in 1914). Most became strong proponents of the view that Arab nationalism could be used to establish British predominance in Arab provinces of the Ottoman Empire. For its part, the French Parti Colonial wove a case based on culture and sentiment as well as interest (including historic ties with the French crown, allegedly stretching back to the Crusades) for France’s acquisition of “La Syrie Integrale” – a Greater Syria stretching from the Taurus Mountains to the Gulf of Aqaba and the Sinai.

Dividing the Fertile Crescent during WWI↑

Despite these rival ambitions, neither France nor Britain had clearly defined war aims in the Middle East before the Ottoman Empire’s entry into the war in November 1914. The attention of policymakers was focused on the post-war disposition of the Empire’s territories once Russia tabled demands for a post-war partition that would give it control of Istanbul and the straits linking the Bosphorus with the Dardanelles, as well as a predominant role in Eastern Anatolia. France now reasserted its Syrian claims, and in February 1915, obtained Britain’s agreement that France had a prior claim on Syria and Alexandretta if plans for the division of the Near East came to fruition. For their part, the British convened the interdepartmental De Bunsen committee in April 1915. Its recommendations stopped short of partitioning the Ottoman Empire, but set out the Great Powers spheres of interest (for Britain, these lay in Palestine and southern Mesopotamia) that looked remarkably similar to the divisions established after the war.

Georges-Picot, the first secretary of the French embassy in London (formerly France’s longstanding Consul in Beirut and a stalwart of the Parti Colonial) presented a maximal version of France’s demands in Greater Syria to an interdepartmental committee of British undersecretaries in November 1915. He then negotiated solely with Mark Sykes, a Conservative Member of Parliament and the representative of the War Office on the committee. An initial agreement was reached by the two men in January 1916 and slightly modified in February 1916. Sykes failed to achieve his aim of annexing to a British sphere all of the territory south of a line drawn between Haifa in Palestine and Kirkuk in what is now northern Iraq. Picot insured that an international regime was agreed for Palestine instead. However, Britain obtained priority rights between the lines Haifa-Takrit and Kuwait-Aqaba, including leave to annex the Tigris-Euphrates valley as far north as Baghdad. For its part, France gained direct control over the Lebanon, coastal Syria, and parts of central Anatolia, as well as a preponderant influence over the Syrian interior and those parts of the province of Mosul that lay to north of the Haifa-Takrit line (the British seem to have wanted this arrangement as a buffer to shield their sphere from Russian Anatolia).

War’s Aftermath: Anglo-French Rivalries Reignited↑

Picot had obtained gains out of proportion to the actual balance of forces in the Levant, a fact the British exploited to claw back most of the concessions made by Sykes after the war. With Russia removed by revolution, there was no longer a need for a buffer shielding Mesopotamia from Anatolia. As a result, Mosul was annexed to the new British League of Nations Mandate in Iraq. In Palestine, the Balfour Declaration was used to replace the international regime agreed with Picot by a purely British Mandate. In eastern Galilee, the frontiers of the new Palestinian Mandate were then pushed northwards to the headwaters of the Jordan River and up the Yarmuk to encompass the Samakh triangle. These enforced concessions rekindled French resentment and eventually led the French authorities in Damascus to refuse cooperation with Britain’s embattled forces in Palestine during the 1936-1939 Palestinian revolt. After the Second World War, France’s enduring hostility led her to retaliate against Britain’s support for Syrian and Lebanese independence by providing support for Jewish terrorist groups in Palestine. Their attacks played a pivotal role in forcing the British into accepting the partition of Mandate Palestine – with ultimately disastrous consequences for their standing in the Arab World. A generation after the agreement, the unintended consequences of Sykes-Picot undermined Britain’s imperial tenure in the Fertile Crescent.

Tariq Tell, American University of Beirut

Section Editor: Abdul Rahim Abu-Husayn

Selected Bibliography

- Andrew, Christopher M. / Kanya-Forstner, Alexander S.: France overseas. The Great War and the climax of French imperial expansion, London 1981: Thames and Hudson.

- Barr, James: A line in the sand. Britain, France and the struggle that shaped the Middle East, London 2011: Simon & Schuster.

- Fromkin, David: A peace to end all peace. Creating the modern Middle East, 1914-1922, London 1989: Penguin.

- Kedourie, Elie: England and the Middle East. The destruction of the Ottoman Empire, 1914-1921, London 1956: Bowes & Bowes.

- Nevakivi, Jukka: Britain, France and the Arab Middle East, 1914-1920, London 1969: Athlone Press.