Introduction↑

The three battles that took place around Gaza and Beersheba between March and November 1917, which ended with a British victory and advance towards the north, signified the end of 400 years of the Ottoman rule in the region, and later, in Palestine. The duration of hostilities went far beyond initial British estimates and resulted in considerable casualties for the British as well as the Ottomans. In spite of the great famine that prevailed in the region from the early phases of the war, and Ahmed Cemal Pasha’s (1872-1922) authoritarian rule, the Ottoman army’s effectiveness and resistance was beyond all the British expectations. As the city was evacuated by Cemal Pasha’s order prior to the hostilities, civilian casualties remained at a minimum.

The Battles↑

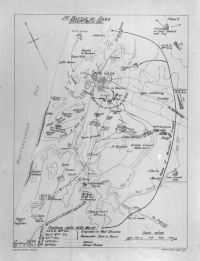

The first battle took place between 18 and 27 March 1917 during which the Ottoman troops won a decisive victory over the British. In this battle, the British command calculated its losses close to 4,000, of which 523 were killed, 2,932 were wounded, and 512 were missing. Five officers and 241 of other ranks, wounded and unwounded, fell into enemy hands. Despite the great number of casualties, the British Commander-in-Chief Archibald Murray (1860-1945) reported the battle to his superiors as a British victory. In contrast, according to Cemal Pasha’s report the Ottoman casualties were as follows: eight officers and 153 soldiers killed, nine officers and 409 soldiers wounded, fifteen officers and 590 soldiers missing. A mobile hospital, a labor squadron, and two batteries had been captured by the British and two further batteries were destroyed by British fire. Murray had attempted a coup de main assault on the town, rather than a prepared battle. This reflected the Egyptian Expeditionary Force’s (EEF) operational approach throughout late 1916 and early 1917 and had been used previously and successfully at Magdhaba and Rafa. Issues such as British command and control arrangements, training, artillery support to the infantry, the role of fog, the impact of limited water supplies, and the skilled tactical defense of the town by the Ottoman army played a major role in the British defeat.

A number of divisional commanders expressed criticism of Charles Dobell (1869-1954) as Eastern Force commander, Major General A.G. Dallas (GOC 53rd Division) was sacked, and a large number of the soldiers (especially the Austrian Light Horsemen and New Zealand Mounted Riflemen) were very angry at having to withdraw as they thought they had taken Gaza. However, shortly afterwards, Murray commenced preparations for a second attack immediately after the first defeat in Gaza. In the three weeks between the first and the second attempt against Gaza, both sides worked actively to make up their deficiencies. On the British side, the railway was expanded closer to Gaza and reached Deir al-Balah, thus reducing the distance between the targeted city and British deployments from about twenty miles to five miles. The Ottoman forces made up their deficiencies in troops to respond to a renewed attack by the British. The Ottoman trenches were reinforced by three regiments in Gaza, two regiments east of the town, two at Hureira, one at Tell al-Sheria, and one in the neighborhood of Huj. Thus, the Tell al-Sheria-Gaza line was deployed as a contiguous front. The Ottoman army in Syria was informed daily about British preparations via the explorations of aviators. The Ottoman army was well prepared for the second encounter and won a second victory between 17 and 20 April, which forced the British troops to withdraw with higher casualties than in the first encounter.

British Military Efforts↑

Following these two defeats, British military authorities understood that they had to take their enemy more seriously and invest greater resources in the EEF to be able to defeat the Ottoman troops defending Gaza and Palestine. Thus, General Murray was replaced by General Edmund Allenby (1861-1936) and greater numbers of guns, soldiers, and ammunitions were sent to Egypt to strengthen the Palestine front. On the other side, Cemal Pasha was dismissed and the German General Erich von Falkenhayn (1861-1922) was appointed in his place, although this could not be considered a countermeasure to the intensifying British efforts on the Gaza front. The objective of the Ottoman-German initiative was to recapture Baghdad, occupied by the British in the spring of 1917, and then, when the army reconquered Mesopotamia, defeat the British in the Sinai and push the Russians back from the Caucasus. Cemal, Friedrich Kress von Kressenstein (1870-1948), and the other high-ranking officers in Syria strongly opposed this plan. The EEF, on the other hand, “had been expanded to ten infantry divisions, and possessed 116 heavy guns. This force was supported by new aircraft, particularly the Bristol Fighter plane, which gave the EEF a technological advantage on their front.” [1]

Immediately after his arrival in Egypt, Allenby made an inspection visit to the Gaza front and sent detailed reports on the deficiencies in the troops that he would command. In summary, he demanded more soldiers in the different divisions and more artillery and pilots to correct the imbalance between British troops and Ottoman troops in Gaza. His requirements were almost fully met as new troops arrived from an evacuated Salonika. The railway constructed from the canal was further extended towards Gaza, which immeasurably facilitated the transfer of troops. Meanwhile, the direction of the planned offensive was shifted to Bi’r-al-Saba. Allenby’s plans were successful and the deadlock at Gaza was broken during the hostilities in October 1917. Shortly after that, on 9 December 1917, the British forces arrived to take Jerusalem.

Ottoman Military Efforts↑

Ottoman troops in Palestine at the time consisted of the Ottoman Eighth Army, under Kress von Kressenstein, with two corps of 40,000 infantry and 1,500 cavalry. These were concentrated on the positions at Gaza. The 4,400 troops of the Seventh Army, commanded by Mustafa Fevzi [Çakmak] Pasha (1876-1950), held the area around Beersheba. Their situation was not promising and casualties were great even before the start of the hostilities: of the 10,000 men of the 20th Infantry Division, for example, only 4,634 arrived at the front fit for fighting. Of the rest, 19 percent were ill and 24 percent were missing. The Ottoman Yıldırım Army had a deficit of 70,000 men from casualties, sickness, and desertion. Disease was the main reason for casualties on both sides during the three battles.

It would be totally erroneous to assume, as would have been reasonable, that the Ottoman general command took British preparations seriously and thus attended to the deficiencies on their side of the Palestine front. Ismail Enver Pasha (1881-1922) insisted on an attack against British forces in Sinai or on shifting some troops from Syria to Iraq to recapture Bagdad. However, both Cemal and the other Ottoman and German commanders in Syria were strongly opposed to such plans and argued for the consolidation of the Syrian front to be able defeat the British. It took a long time to persuade Enver Pasha of the necessity of creating a defense line beyond Gaza. When the Ottoman army in Syria started to take measures in order to counter the third British attack against Gaza, the British were about to complete their preparations for the occupation of the city.

M. Talha Çiçek, Istanbul Medeniyet University

Section Editor: Abdul Rahim Abu-Husayn

Notes

- ↑ Johnson, Rob: The Great War and the Middle East, Oxford 2016, p. 191.

Selected Bibliography

- Cemal Paşa, Ahmed: Hatırat, 1913-1922, Dersaadet 1922: Ahmed İhsan ve Şüreka Matbaası.

- Çiçek, M. Talha: War and state formation in Syria. Cemal Pasha's governorate during World War I, 1914-1917, London; New York 2014: Routledge; Taylor & Francis Group.

- Falls, Cyril: Military operations. Egypt and Palestine, volume 2, London 1930: His Majesty's Stationary Office.

- Hughes, Matthew: Allenby and British strategy in the Middle East, 1917-1919, London 1999: Frank Cass.

- Hughes, Matthew: General Allenby and the Palestine Campaign 1917-18, in: Sheffy, Yigal / Shai, Shaul (eds.): The First World War. Middle Eastern perspective, Tel Aviv 2000: Israel Society for Military History, Tel-Aviv University, pp. 95-104.

- Hughes, Matthew: General Allenby and the Palestine Campaign, 1917-18, in: Journal of Strategic Studies 19/4, 1996, pp. 59-88.

- Johnson, Robert: The Great War and the Middle East. A strategic study, Oxford 2016: Oxford University Press.

- MacMunn, George / Falls, Cyril: Military operations. Egypt and Palestine, volume 1, London 1928: His Majesty's Stationery Office.

- Woodward, David R.: Forgotten soldiers of the First World War. Lost voices from the Middle Eastern front, Stroud 2006: Tempus.