Military Career↑

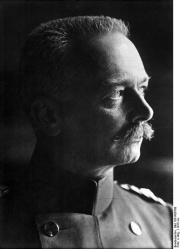

Erich von Falkenhayn (1861-1922) was a Prussian General of the Infantry, Prussian Minister of War (1913-1915) and Chief of Staff (1914-1916). Falkenhayn came from a West-Prussian Junker family, where the military played a dominant role; one of his brothers, Eugen von Falkenhayn (1853-1934), was also a general. Falkenhayn already entered cadet school at the age of ten. He became an officer and, after showing promise, was sent to the military academy. His career as a staff officer took an unusual turn when he took leave in 1896 and went to China as a military instructor. Contrary to what was speculated at the time, gambling debts did not motivate this move, but rather career prospects and financial considerations (a higher salary). It was also undertaken with the explicit consent of the emperor. In 1899, Falkenhayn worked in Kiaochou. In 1900, he was a General Staff Officer in the East-Asian Expeditionary Force and then held the same post in the East-Asian occupational brigade. At that time, he attracted the attention of Heinrich, Prince of Prussia (1862-1929) and the emperor. It was to them that he primarily owed his “comet-like” ascent, after he returned to Germany in 1903, along with his soldierly prowess.

Prussian War Minister↑

Falkenhayn’s rapid and successful career reached a momentary climax when he was appointed Prussian Minister of War in July 1913. Making his debut in the Saverne Affair, he contributed to its parliamentary escalation as a result of his overly brusque demeanor in the Reichstag.

Not least due his soldierly impulse to take action, Falkenhayn longed for a European war, even if this meant it would only benefit the USA and Japan, as he suspected in 1912. During the July Crisis in 1914, he participated in his capacity as Prussian Minister of War in the crucial deliberations in Berlin over going to war. He was also at the meeting on 5 July 1914, when German leaders extended to Austrian representatives in Berlin a blank check, assuring them that they would have Germany's full support however they decided to deal with Serbia. Falkenhayn pushed for early mobilization, partly out of military considerations, and pressured Wilhelm II, German Emperor (1859-1941), who was suddenly in favor of securing the peace. When war finally broke out, Falkenhayn could not hide his enthusiasm. He told Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg (1856-1921): “Even if we perish over this, it will still have been worth it.”[1]

Chief of Staff↑

As Minister of War at the headquarters, Falkenhayn was soon installed as the new Chief of Staff in August 1914 due to the fact that Helmuth von Moltke (1848-1916) was considered mentally unstable and excessively nervous. Leadership of the army was transferred to him in September 1914 after the Battle of the Marne. He had been endorsed as a candidate by the emperor and the Military Cabinet. First, he tried to successfully turn the tide of the attack in the West, which, however, came to a bloody and ill-fated end in the Battle of Ypres. The military setbacks at Ypres permanently damaged his reputation.

In November 1914, Falkenhayn recognized that a decisive victory was neither possible in the East nor the West. He, therefore, based his strategy on holding the line until a negotiated peace could be achieved. He also informed the Chancellor of the need to end the war through political means. However, neither the Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg, nor the victors of Tannenberg, Paul von Hindenburg (1847-1934) and Erich Ludendorff (1865-1937), liked idea of a peace settlement. Besides having personal motives, the latter also thought differently when it came to warfare. Both Hindenburg and Ludendorff were certain that it would be impossible to negotiate peace, as they were convinced of their enemies’ committed stance to Germany’s annihilation. To achieve victory, they wanted to first defeat the Russians and then the Western powers. While Falkenhayn also attributed to Great Britain the same destructive tendency, he nonetheless believed that Germany lacked the forces to secure victory in the East. He argued that the Western Front should not be unduly weakened, and that the Russians could always retreat into the expanse of their territory, which would make operational decisions virtually impossible. Falkenhayn recommended negotiations with France, but above all with Russia, dispensing with annexations if necessary. Bethmann Hollweg was caught between the two lines of this debate. However, he was not sufficiently convinced by Falkenhayn’s approach or his military abilities to fully cooperate with him. There was also the problem that Falkenhayn had made few friends because of his attitude of "mocking superiority".

In the spring of 1915, Falkenhayn energetically sought to preserve Italian neutrality, although his efforts were ultimately in vain. It was partly for this reason that he also planned a diversionary attack on the Eastern Front to support the Austrians against the Russians and to discourage Italy. The attack at Gorlice-Tarnow on 1 May 1915 was a tremendous success for the Central Powers. It was not only arguably a decisive blow against the Russians, but it also stabilized the Habsburg Monarchy so that it could continue the war for another three and a half years, despite Italy’s entry into the war on 23 May 1915. The Russian troops were forced to retreat under huge losses and subsequently surrender all of Russian Poland. Falkenhayn, nevertheless, urgently advocated for a separate tentative peace agreement that would waive reparations and annexations. The tsarist government, however, rejected the idea.

In the fall of 1915, Falkenhayn launched an attack on Serbia, which turned out to be a complete triumph. The whole country was occupied, and the Allies transported the remnants of the Serbian army to Salonika, where it was reconstituted. The largely favorable military situation in late fall of the same year encouraged Falkenhayn to believe that peace could be achieved by enfeebling the Western enemies. With regard to Russia, he thought they were incapable of going on the offensive. He intended to weaken the English through unrestricted submarine warfare and the French by attacking Verdun. Both operations were aimed at forcing the opponents to the negotiating table. Falkenhayn still held fast to the view that a classic decisive victory was out of the question. While the Chancellor and the emperor vetoed the prospect of submarine warfare owing to the influence of the United States, the attack on Verdun began on 21 February 1916. Falkenhayn wanted to either take the contour line to the east of the city, position artillery, and thereby force the French into devastating counterattack or to abandon the city altogether. At the same time, the British needed to be provoked into a making a hasty diversionary attack. In order to defend against it, Falkenhayn had withheld the majority of the army’s reserves. The company soon ran aground, however, and the critical contour lines could only be partially taken. This was mainly due to the reserves’ inadequate resources and the decision against simultaneously attacking on the western bank to neutralize the risk of auxiliary fire. Falkenhayn and the leadership of the 5th Army entrusted with the attack could not bring themselves to relinquish the attack’s initial successes (including the taking of Fort Douaumont). Instead of breaking off the combat, they continued the attack. Falkenhayn’s prestige suffered, especially when the Allies began their multi-front attack in July 1916 that had been arranged in the fall of 1915 (Brusilov Offensive, Battle of the Somme, and the Battles of the Isonzo). The Central Powers subsequently fell under extreme duress. There is no doubt that Falkenhayn’s defensive strategy, as well as his military deployments, were successful on the whole. Indeed, the Allied attacks never really penetrated. Nonetheless, when Romania declared war at the end August 1916, Falkenhayn was relieved and replaced by Hindenburg and Ludendorff, who had been scheming against him and pressing for his removal since the end of 1914.

Conclusion↑

In the final analysis, Falkenhayn pursued a cautious strategy that was adapted to the forces of the Central Powers and advocated a political end to the war that dispensed with vague annexation plans. He understood, before most other military leaders of the First World War, the inherent difficulty of going on the offensive in trench warfare. Despite these positive aspects of Falkenhayn’s tenure, however, his ultimately unsustainable strategy at Verdun – especially his drawn-out decision to simply call off the failed attack – and his plan to commence with unrestricted submarine warfare must be strongly criticized.

Falkenhayn later took on the command of the 9th Army, which was deployed against Romania. Here, he found an opportunity to put his soldierly skills to the test. He was less successful afterwards, however, as the commander of Army Group F in Turkey – the planned attack on Baghdad did not transpire and he failed to hold onto Jerusalem. Still, he was able to hinder the Ottoman authorities’ planned “relocation” of the Jewish settlers in Palestine, which could have easily ended in a bloodbath. A final command in Belarus after the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk involved mainly administrative tasks.

After the war, in 1920, Falkenhayn wrote his memoirs, “Die Oberste Heeresleitung 1914-1916 in ihren wichtigsten Entschließungen” (“Supreme Army Command 1914-1916 and its most important Resolutions”). Among other things, he sought to justify the attack on Verdun by citing the allegedly much higher losses on the French side. Falkenhayn died in April 1922 in Potsdam from kidney failure.

Holger Afflerbach, University of Leeds

Section Editor: Mark Jones

Translator: Christopher Reid

Notes

- ↑ “Wenn wir auch darüber zugrunde gehen, schön wars doch.” Riezler-Tagebuch, 22.11.1914, cited in Afflerbach, Holger: Falkenhayn. Politisches Denken und Handeln im Kaiserreich, Munich 1996, p. 170.

Selected Bibliography

- Afflerbach, Holger: Planning total war? Falkenhayn and the Battle of Verdun, 1916, in: Chickering, Roger / Förster, Stig (eds.): Great War, total war. Combat and mobilization on the Western Front, 1914-1918, Washington, D.C.; Cambridge; New York 2000: German Historical Institute; Cambridge University Press, pp. 113-131.

- Afflerbach, Holger: Falkenhayn. Politisches Denken und Handeln im Kaiserreich, Munich 1996: Oldenbourg.

- Foley, Robert: German strategy and the path to Verdun. Erich von Falkenhayn and the development of attrition, 1870-1916, Cambridge; New York 2005: Cambridge University Press.

- Janssen, Karl-Heinz: Der Kanzler und der General. Die Führungskrise um Bethmann Hollweg und Falkenhayn (1914-1916), Göttingen 1967: Musterschmidt.

- Janssen, Karl-Heinz: Der Wechsel in der Obersten Heeresleitung 1916, in: Vierteljahreshefte für Zeitgeschichte 7/4, 1959, pp. 337-371.

- Jessen, Olaf: Verdun 1916. Urschlacht des Jahrhunderts, Munich 2014: C. H. Beck.

- Ritter, Gerhard: The sword and the scepter. The problem of militarism in Germany, volume 2, Coral Gables 1970: University of Miami Press.

- Ritter, Gerhard: The sword and the scepter. The problem of militarism in Germany, volume 3, Coral Gables 1972: University of Miami Press.

- Ritter, Gerhard: The sword and the scepter. The problem of militarism in Germany, volume 4, Coral Gables 1973: University of Miami Press.

- Ritter, Gerhard: Staatskunst und Kriegshandwerk. Die Hauptmächte Europas und das wilhelminische Reich, volume 2, Munich 1960: Oldenbourg.

- Ritter, Gerhard: Staatskunst und Kriegshandwerk. Die Tragödie der Staatskunst. Bethmann Hollweg als Kriegskanzler, volume 3, Munich 1964: Oldenbourg.

- Ritter, Gerhard: Staatskunst und Kriegshandwerk. Die Herrschaft des deutschen Militarismus und die Katastrophe von 1918, volume 4, Munich 1968: Oldenbourg.