The Situation in Spring 1915↑

In spring 1915, the situation of the Central Powers on the Eastern Front was critical. Having suffered severe losses during the battles of summer/autumn 1914 and the Carpathian Winter War of 1914/1915, the military forces of the Habsburg Empire had been weakened considerably and were expected to collapse under the next attack. Moreover, large parts of the crown lands Galicia and Bukovina had fallen into Russian hands following the retreat of the Austro-Hungarian forces in summer 1914, a loss that had severely damaged the reputation of the Habsburg Monarchy. Its evident military weakness left Vienna in a most uncomfortable position, especially since it was obvious that Italy and Romania, which had remained neutral in 1914, were tempted to join the ranks of the Entente in order to benefit from the seemingly unavoidable defeat of Austria-Hungary.

For Germany, the situation was likewise unfavourable, though for different reasons. Contrary to its ally, the German army had been more successful against the Russians on the Eastern Front and had even managed to push back the Tsarist forces into Russian Poland in December 1914. However, since Germany was engaged in a two-front war on the Eastern and Western Fronts, it seemed only a matter of time until its forces would be overextended and defeated by one of the Entente Powers.

Russia, by contrast, believed that it was in a much better strategic position than the Central Powers in the spring of 1915. The Tsarist army had likewise suffered considerable losses in the battles of 1914 and early 1915, but had been able to recover due to its reserves of men and war materiel. Having experienced defeat against German forces in late 1914 and early 1915, the Russian leadership turned its attention to the southern part of the Eastern Front in spring 1915, hoping to break the Austro-Hungarian army in an upcoming offensive and, consequently, to knock the Habsburg Monarchy out of the war.

Planning the Campaign↑

Germany and Austria-Hungary both considered returning to offensive warfare on the Eastern Front in spring 1915, though with different aims. The primary objective of the Habsburg Monarchy was the liberation of territories occupied by the Tsarist army, especially since a major military success of the Austro-Hungarian army was expected to leave a strong impression on Italy and Romania, convincing them to maintain their neutral status. Germany, on the other hand, aimed to crush the Russian forces on the Eastern Front, eliminating the Tsarist army as a military factor for the time being and preventing the imminent military collapse of the Habsburg Monarchy. After stabilizing the situation in the East, the German high command planned on sending a large part of its forces to the Western Front, where they were to deliver a war-deciding blow. Since both objectives could only be accomplished if the Central Powers joined forces, the German and Austro-Hungarian general staffs, which had until then waged war independently for the most part, reluctantly agreed to draw up a plan for a joint campaign on the Eastern Front.

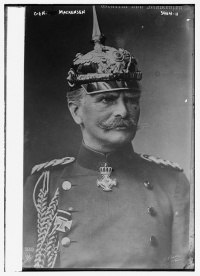

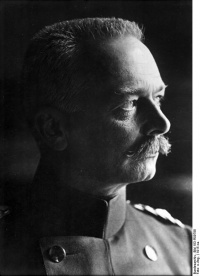

Although a much larger campaign was originally proposed, the Austro-Hungarian and German chiefs of staff, Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf (1852–1925) and Erich von Falkenhayn (1861–1922), finally agreed on a conventional, much smaller offensive to take place east of Cracow near the town of Tarnów. The region was chosen because its railway lines facilitated the fast deployment of troops and materiel, while the river Vistula to the north and the Beskid Mountains to the south provided natural protection of the assailants’ flanks. The joint forces of the Central Powers (German 11th Army and Austro-Hungarian 4th Army), commanded by German General August von Mackensen (1849–1945), consisted of eight Austro-Hungarian and ten German infantry divisions (about 220,000 officers and men) as well as some 900 artillery guns.

The opposing forces, the Russian 3rd Army under the command of General Radko Dimitriev (1859–1918), occupied positions on the heights near Tarnów and almost matched the numbers of the combined German and Austro-Hungarian attacking force. However, the Russian troops in the sector were mostly inexperienced, lacked artillery, and most of their trenches provided only insufficient cover against artillery fire. Moreover, even when Russian reconnaissance reported the deployment of large numbers of German troops in the Gorlice-Tarnów region in mid-April 1915, the 3rd Army was not reinforced, since most available troops were concentrated in the Carpathians for an imminent attack.

Breakthrough↑

The joint German-Austro-Hungarian offensive began on the morning of 1 May 1915, with intense artillery bombardment, followed by an assault on the Russian positions. Although the defenders initially put up stiff resistance and available reserves were deployed swiftly, the Russians were soon overwhelmed by well-guided artillery fire and the onslaught of about 40,000 German and Austro-Hungarian soldiers in the first wave of attack. By the evening of the first day, the troops of the Central Powers had advanced more than ten kilometres into the enemy’s zone of defence, while the Russians were struggling to rally scattered troops, bring up reinforcements and re-establish a line of defence. All efforts, however, proved futile as the German and Austro-Hungarian troops kept advancing, while arriving Russian reinforcements were rushed into battle and consequently often isolated, outflanked and defeated. Within only eight days, the 3rd Army was almost completely destroyed, forcing the Russian high command to order a general retreat to a new defensive line along the river San. When this line was also penetrated by advancing German and Austro-Hungarian troops, the Stavka ordered the complete withdrawal of all Russian forces from Galicia on 21 June 1915. By that date, which marked the official end of the Gorlice-Tarnów campaign, about 100,000 Russian soldiers had been killed or wounded in action, and another 250,000 captured by the Austro-Hungarian and German forces, along with large amounts of weapons and other war materiel. At the same time, the Central Powers had lost about 90,000 men, who had been killed, wounded or gone missing.

Conclusion↑

The Gorlice-Tarnów Offensive was a striking success for the Central Powers, accomplishing all its objectives in less time than expected. Not only were the Russians driven back from Galicia, the offensive also laid the basis for the successful Austro-Hungarian/German campaign in summer 1915, when the Russian army was forced to beat a retreat along the entire Eastern Front, with huge losses of men and war materiel. Especially the loss of weapons and equipment, which could not readily be replaced by Russia’s insufficient industrial production capacities, neutralized the Tsarist army as a fighting force for months to come. This circumstance proved crucial for Austria-Hungary when Italy declared war on it in May 1915. Since the Russian army was retreating in chaos at the time, the Habsburg Monarchy could transfer a considerable number of troops from the Eastern Front to the new theatre of war, where they managed to stop the Italian attacks.

It is puzzling, however, that despite the striking success of the Gorlice-Tarnów campaign, Germany and Austria-Hungary did not continue their close military cooperation. Instead, Vienna and Berlin, despite being allies, went back to waging war almost independently of each other, coming together only in times of crisis. This fact, which can be attributed above all to distrust between Conrad von Hötzendorf and Falkenhayn, as well as to general disagreements regarding the question on which front a crucial blow could be delivered, obviously reduced the Central Powers’ already slim chances of deciding the conflict in their favour.

Richard Lein, Austrian Academy of Sciences

Section Editor: Tamara Scheer

Selected Bibliography

- Airapetov, Oleg Rudol’fovich: Uchastie Rossiiskom Imperii v Pervoi Mirovoi Voine (1914-1917) (The participation of the Russian Empire in World War I (1914-1917)), 2 volumes, Moscow 2014: Universitet Knizhnyi Dom.

- Der Weltkrieg 1914-1918. Die militärischen Operationen zu Lande. Die Operationen des Jahres 1915. Die Ereignisse im Westen im Frühjahr und Sommer, im Osten vom Frühjahr bis zum Jahresschluss, volume 8, Berlin 1932: Mittler, 1932.

- DiNardo, Richard L.: Breakthrough. The Gorlice-Tarnów campaign, 1915, Santa Barbara 2010: Praeger.

- Glaise von Horstenau, Edmund: Österreich-Ungarns letzter Krieg 1914-1918. Das Kriegsjahr 1915. Vom Ausklang der Schlacht bei Limanowa-Łapanów bis zur Einnahme von Brest-Litowsk, volume 2, Vienna 1931: Militärwissenschaftliche Mitteilungen.

- Rauchensteiner, Manfried: The First World War and the end of the Habsburg monarchy, 1914-1918, Vienna 2014: Böhlau.

- Stachelbeck, Christian: Militärische Effektivität im ersten Weltkrieg. Die 11. Bayerische Infanteriedivision 1915-1918, Paderborn 2010: Schöningh.

- Stone, David R.: The Russian army in the Great War. The Eastern Front, 1914-1917, Lawrence 2015: University Press of Kansas.

- Stone, Norman: The Eastern front, 1914-1917, London; Sydney; Toronto 1975: Hodder and Stoughton.

- Tunstall, Graydon A.: Blood on the snow. The Carpathian winter war of 1915, Lawrence 2010: University Press of Kansas.