Introduction↑

On 12 October 1917 the Rev. Capt. Thomas Nangle (1889-1972), Roman Catholic Chaplain of the Newfoundland Regiment, gave a recruiting address to the Benevolent Irish Society following his temporary return to St. John’s from the European battlefront. He had spoken to the same group a year earlier when the emotions of the Regiment’s losses at Beaumont Hamel in the Battle of the Somme were still raw. Now he provided the society with a “war souvenir in the form of part of the propeller blade of a German airship” that he recovered from the battleground and inspirationally spoke of the “doings of the regiment at the front.” A week later, he addressed a much larger audience about the “Trail of the Caribou.”[1] His storytelling over the next decade became an integral part of how Newfoundlanders and Labradorians viewed the Regiment, whose participation remained at the fore of memory during and after the war. While the Regiment was the embodiment of the dominion’s service, there were other Newfoundlanders who served in other formations or units and at home whether it was in the Newfoundland naval reserve, the forestry corps or the merchant marine as well as in the forces of Canada, Britain and other countries. What follows is an account of the Regiment’s involvement in the Great War.

The Regiment↑

Three days after Britain’s declaration of war against Germany on 4 August 1914, the government of Newfoundland led by Prime Minister Edward Morris (1859-1935) committed to a land force of 500 men for service abroad as Newfoundland had no local militia.[2] The first group of enthusiastic recruits became known as the Blue Puttees and many were residents of St. John’s who had been members of the city’s boys’ church-related paramilitary clubs.[3] The uniform was designed by two members of the equipment organizing committee who had served in the Boer War (1899-1902) with Britain’s Colonial Division. The Newfoundland regimental dress partly resembled the First Regiment Brabants Horse of the Colonial Division, but the blue puttees were added to complement the cotton khaki uniforms as there was no woollen khaki material available at the time in St. John’s. Blue was the colour used by the Church Lads’ Brigade, a popular Church of England boys’ paramilitary group.[4] On 4 October, 537 men boarded the Newfoundland-owned steamer Florizel in St. John’s and joined a convoy of thirty-two Canadian ships with over 32,000 volunteers escorted by seven warships.

The Blue Puttees arrived in England on 14 October where they were fitted with regular army puttees.[5] Initially camped near the First Canadian Contingent at Salisbury Plain, the Newfoundlanders were first under Canadian control and placed under Col. E.B. Clegg (1864-1945), who was soon succeeded by British army Lt. Col. R. de H. Burton (1861-c. 1942). His British successor, Lt. Col. Arthur Lovell Hadow (1877-1968), commanded the Regiment from December 1915 to December 1917.[6] The Newfoundlanders feared that such close proximity to the Canadian contingent would create the impression that they were Canadian. As soldier Owen Steele (1887-1916) noted in his diary, “the larger Canadian presence at the camp created many occasions for mistaken identity.”[7] Newfoundlanders were conscious of their national identification and the Regiment gave them a strong “sense of community.” Their distinctiveness was noted in their selection of the caribou, an animal indigenous to Newfoundland, as the badge symbol for the Regiment.[8] There were often good-natured tensions between the non-commissioned members of the Regiment and some of the British staff-sergeants and officers who dealt with them, as a recently published memoir by Howard Morry (1885-1972) shows (regimental no. 726). In it, Morry writes that the reason why the British soldier “disliked us so much” was probably because the Newfoundlander’s daily pay was greater, $1.10 a day compared to ten cents a day, and “besides we laughed at them for saluting their officers at every turn and twist, and being scared of their NCOS.”[9] Family and friends in Newfoundland were kept informed of the Regiment’s activities and training by members such as Betts’ Cove volunteer Pte. Frank Lind (1879-1916) who wrote regularly to the Newfoundland press.[10]

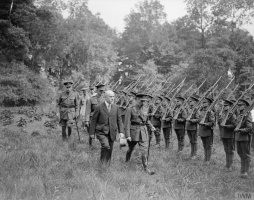

In December 1914 the Regiment’s first battalion transferred from the mud of Salisbury Plain to the hard ground of Fort George at Inverness, Scotland to continue their training before moving in mid-February 1915 to Edinburgh. A second battalion of the Newfoundland Regiment left Newfoundland on 5 February 1915, followed by a third on 22 March, bringing the Regiment’s strength to about 1,000 men. In early May the Regiment again moved to Stobs Camp, about fifty miles from Edinburgh where the Regiment on 10 June received its regimental colors. F Company arrived on 12 July bringing the complement of the Regiment to 1,500 men ready for battle with 500 men in reserve.[11] The Regiment spent several weeks at Edinburgh where it guarded Edinburgh Castle (the only non-Scottish troops ever to do so) and finally went on to the Regimental Depot at Ayr to complete training. Companies A, B, C and D on 2 August left Ayr for Aldershot where nearly 250,000 British troops were training. There, Blue Puttee Sydney Frost (1893-1985) later observed, “everyone sensed the day was drawing near when we would be receiving marching orders for the Front and we presumed it would be France or Belgium.”[12]

Gallipoli↑

At Aldershot the Regiment was attached to the 88th Brigade of the 29th Division and Companies A, B, C and D were sent to the Mediterranean in September where Allied forces had been engaged since April in a stalemated effort to take the Dardenelles from Turkey.[13] The Newfoundlanders were the only unit from North America to fight at Gallipoli. After landing at Suvla Bay, the Regiment saw battle first on 22 September 1915 and suffered its first battle fatality when Private Hugh Walter McWhirter (c. 1894-1915) of the Bay of Islands died in action. Subsisting on a steady diet of “bully beef and hard biscuit with an occasional tin of jam and a tin of Maconochie rations” and fighting a constant nuisance of “flies and lice,”[14] the Regiment enjoyed some success and participated in the taking of a hill nearer to Constantinople than any other ground taken by Allied forces. The hill (knoll), styled “Caribou Hill,” saw a daring night attack by a small squad led by Lt. J.J. Donnelly (c. 1882-1916), who won the Military Cross for his heroics and was later killed in battle in France. Two other soldiers, Sgt. Walter Greene (1893-1917) and Pte. Richard Hynes (c. 1891-1916), were awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal, giving the Regiment its first distinctions in battle.[15] The Regiment remained at the front lines until December when it was evacuated to Murdos; it returned later to Cape Helles to serve as the rearguard under Lt. Owen Steele on 9 January 1916 with the withdrawal of Allied forces defending that position. In all, the Regiment had 1,167 men in service in the Gallipoli campaign; its casualty rate was 55.4 percent, including forty-one who were killed in action or died of their wounds, eighty-four who were evacuated because of wounds, and another 522 who suffered various illnesses including dysentery, frostbite and trench foot. The Regiment’s first “baptism of fire” was costly.[16]

Tragedy at Beaumont Hamel↑

After rest at Suez, the Regiment left Egypt on 14 March on the troopship Alaunia, arriving on 22 March at Marseilles, France, and then went by train to Pont-Remy, near Abbeville at the mouth of the Somme. In late March 1916 Britain and France had been preparing for a major assault on German lines and the Battle of the Somme began on 1 July and lasted until November 1916. The Regiment played an active role in constructing support and communication trenches along the front lines and, by the end of June, it had been brought up to full strength by new recruits from the Ayr Depot. One draft of forty-four men arrived the day before 1 July to join the fight and they were soon to be part of the slaughter that took place without the Newfoundlanders firing a single shot.[17] 721 members of the Regiment serving with the 29th Division advanced on well-fortified German lines under the barrage of heavy machine gun fire near the village of Beaumont Hamel. Within thirty minutes about 386 men had been killed or gone missing in action. Another 396 were wounded. All of the twenty-five officers were either killed or wounded. Only about sixty-eight men later reported for duty call.[18] The frontline, recalled veteran Howard Morry, was a “butcher shop in hell, with our wounded dragging themselves in and falling down in the trench.” It was a senseless advance, as most of the casualties were inflicted before the men reached the line.[19]

It was nearly a month for the full extent of the tragedy at Beaumont Hamel to become known to the Newfoundland public. Both the British army and the Newfoundland government had prepared Newfoundlanders for their losses by emphasizing that the heroic sacrifices at the Somme were not in vain. It was announced by British commander Brigadier-General Douglas Edward Cayley (1870-1951) that the 29th Division had been put into the offensive against the “strongest part of the German line, and, as it proved, impregnable to direct assault.” He wrote Newfoundland Governor Sir Walter Davidson (1859-1923) on 18 July that

Field Marshall Sir Douglas Haig (1861-1928), commander in chief of the British Expeditionary Force, similarly wrote Davidson on 9 July that “Newfoundland may well feel proud of her sons. The heroism and devotion to duty they displayed on July First has never been surpassed.”[21] The Regiment did not return to battle until October 1916. Restocking the depleted ranks became a national urgency in Newfoundland amid the mourning of the Regiment’s loss, as the country vowed to keep the Regiment at full force and in the field through active voluntary recruitment. By April 1918 Newfoundland implemented conscription, but no conscripted troops ever participated in battle.[22]

Regimental Honors↑

The Regiment’s next engagement was Gueudecourt on 12 October 1916 against a strong German counter-offensive. The Newfoundland Regiment held ground until reinforcements from the 88th Brigade arrived to buttress the defense.[23] The Regiment’s action prompted the 88th’s Brigade Commander Brigadier-General D.E. Cayley to write Governor Davidson on the “grand services to the Empire which your gallant Regiment has rendered.”[24] The Regiment suffered 120 casualties killed or missing in action; 119 were wounded but survived.[25]

The Regiment fought other lesser battles at Les Beoufs, Le Transloy and Sailly-Saillisel,[26] but its next major battle was at Monchy-le-Preux on 13 April 1917 as part of the Battle of Arras that had seen the Canadians capture Vimy Ridge on 9 April. With the Regiment and the 1st Essex in the lead, the 29th Division took the town of Monchy-le-Preux which provided a commanding view of the area and the nearby “Infantry Hill.” Those encounters saw light German resistance which was followed by a fierce counter-attack. Both regiments found themselves surrounded on three sides and no Allied forces were in place between the Germans and Monchy-le-Preux. During the desperate struggle, the Regiment’s commanding officer, Lt. Col. James Forbes-Robertson (1884-1955), who received the Distinguished Service Order, Lieutenant Kevin Keegan (1894-1948) - a Military Cross - and eight other soldiers - Military Medals - advanced towards the oncoming enemy, and from a trench held off the Germans for four hours to allow time for other British reinforcements to be rushed forward in order to prevent the loss of Monchy-le-Preux.[27] The Regiment suffered further losses with 183 killed or missing in action; another 141 were wounded and 153 men were taken prisoner. It was, Frost later recalled, “second only to Beaumont Hamel in the entire War” as far as losses to the Regiment were concerned.[28]

In mid-August the Regiment engaged the enemy at Langemarck which resulted in twenty-six killed and eighty-seven wounded. For three weeks from 28 August the Regiment rested at Penton camp, near Proven, and returned to fight again in the Ypres Salient in October in the Battle of Poelcappelle where it achieved its objectives at the cost of sixty-seven killed and 127 wounded. The 29th Division and the Regiment were then withdrawn from the area with the Regiment resting, re-equipping and awaiting reinforcements.[29]

The Regiment’s next significant engagement was with the Allied assault on the Hindenburg Line in November 1917 with the goal of capturing the town of Cambrai, ten kilometers north of Masnieres. This involved crossing the St. Quentin Canal at Masnieres. The British Third Army launched the attack on 20 November. Tanks assigned to the attack were destroyed by German artillery fire, but the Regiment’s 553 men advanced with the 29th Division, capturing German guns and about 150 prisoners as it crossed the Canal and fought its way, over the next ten days, up the bank of the Canal to Masnieres. The Regiment fought off a German counter-offensive designed to cut off the Allied forces. The Regiment suffered severe casualties, including about 109 killed or missing in action and 384 wounded.[30] One of those killed was an aboriginal soldier from Labrador, John Shiwak (1889-1917), the Regiment’s leading sniper. The Regiment’s recent achievements in battles earned it the title “Royal,” the only Regiment in the war to be honored with such a distinction.[31]

Other battles followed, but with reduced ranks and reinforcements slow to emerge from the Depot (located at Winchester, England since January 1918), the Regiment spent five months in early 1918 in Reserve. The Regiment conducted garrison duty for General Douglas Haig at his headquarters in Montreuil.[32] Its heroic efforts in 1917 battles reinforced public views in Newfoundland that recruiting efforts had to be maintained to ensure the Regiment survived as a separate fighting unit.[33] On 29 May 1918 Newfoundland Governor Sir Charles Harris (1855-1947) informed the public that he had been reassured by Haig that the Regiment, once it was sufficiently reinforced, would resume its place in the 29th Division after having been withdrawn on 29 April for manpower shortages.[34] The Regiment was transferred in September to the 28th Brigade of the 9th Scottish Division under Major-General Hugh Tudor (1871-1965) and the Regiment was once again up to battle strength. On 14 October, the Regiment fought at Courtrai, Belgium. The fighting was bitter and costly, especially when the Regiment’s progress was stalled by a German gun emplacement. A small group of soldiers attacked the German stronghold with a Lewis machine gun and, aided by extra ammunition brought by seventeen year-old Private Thomas Ricketts (1901-1967), took out the German emplacement. Ricketts travelled repeatedly over the open battleground to bring ammunition to his platoon, a feat which won him the Victoria Cross. Fighting in the general area lasted until Germany surrendered officially on 11 November. During the month of October, the Regiment suffered 334 casualties consisting of forty-one killed, 171 wounded, fifteen missing, and 102 reported sick.[35]

Some 6,241 men had enlisted in the Regiment; the number of casualties was 3,619. This included 1,305 deaths and 2,314 men wounded.[36] Of the initial Blue Puttee contingent, 31.4 percent were either killed or died of their wounds, while another 37.3 percent were wounded in action. Only 110 survived the war “apparently unscathed.”[37] A large number of the killed were underage soldiers, and records indicate that 272 teenagers lost their lives with the Regiment with thirty-nine of that group killed at Beaumont Hamel.[38] With the end of war, the 9th Division was chosen as one of two British divisions for the occupation of Germany and the Regiment remained at Hilden until February 1919. The Regiment left for Liverpool on 22 May 1919 aboard the Canadian passenger steamer S.S. Corsican and arrived in St. John’s on the morning of 1 June amidst dense fog outside the harbor and “torrents of rain.” Even so, thousands of well-wishers lined the docks to welcome their heroes home.[39]

Conclusion↑

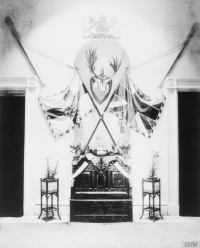

To help integrate veterans back into civilian life, the Newfoundland government established a Civil Re-establishment Committee on 18 June 1918. The veterans had a strong advocate in Nangle and had their own lobby group, the Great War Veterans’ Association (GWVA) of Newfoundland, which had originated in the Soldiers and Rejected Volunteers Association, formed in St. John’s on 11 April 1918. From 1920 they also had their magazine, The Veteran, to inform members of veterans’ related issues and to keep the story of their wartime contribution alive.[40] On 20 August 1918 the association refashioned itself along the lines of the Great War Veterans’ Association of Canada, which had been established in 1917. Two issues dominated the affairs of the GWVA in the early 1920s: the improvement of pensions and the project of a national memorial to honor Newfoundland’s war dead. Pensions for veterans and their dependents had been approved by the government in 1917 with payments subject to annual adjustments. The GWVA lobbied hard for redress and made significant gains in veterans’ pensions and their re-establishment in civilian life. The organization was likewise successful in the war memorial project. Under Nangle’s leadership, the GWVA conducted a public fund-raising campaign for the monument, which was situated at King’s Beach, St. John’s. A ceremony was held on 1 July 1924 at which Field-Marshal Earl Haig unveiled the memorial. Similar memorials to veterans were erected in many rural communities in the 1920s and the Newfoundland government established battlefield memorial parks in Europe, four in France (one at Beaumont Hamel on 7 June 1925) and a fifth at Contrai, Belgium.[41]

The history of Newfoundland’s participation in the Great War has been publicly presented through the lens of the role played by the Regiment.[42] The Blue Puttees in particular have had a special place in the hearts of Newfoundlanders and their annual reunions were events of special note for the press and public well into the 1970s. Newfoundland’s small population and the valiant efforts of the Regiment had made the loss of life and casualties so intimate that its people celebrated in both its victories and the tragedy of each casualty. The Regiment came to symbolize the supreme sacrifice made by Newfoundlanders in the Great War, and for 2016 the Newfoundland government has major commemorative events planned for the Beaumont Hamel centennial.[43] Efforts over the years to write the history of Newfoundland’s involvement in the Great War, both on the war and home fronts, have been dominated by the Regiment’s role. Indeed, as journalist Patrick Thomas McGrath (1868-1929) observed in 1928, a “record for all time” has yet to be achieved of all those who served in uniform, nor has the account of how the war affected the home front been written.[44] One scholar has observed recently of the “thousands of Newfoundlanders” working “directly and indirectly for the war effort, many in voluntary associations … their efforts have been largely forgotten.”[45]

Melvin Baker, Memorial University of Newfoundland

Section Editor: Tim Cook

Notes

- ↑ Browne, Gary/McGrath, Darrin: Soldier Priest in the Killing Fields of Europe. Padre Thomas Nangle: Chaplain to the Newfoundland Regiment WW1, St. John’s 2006, p. 29; Evening Advocate, 13, 19 October 1917; and Nangle, Thomas: The Trail of the Caribou. Lecture given at the Casino Theatre, 19 October 1917.

- ↑ Baker, Melvin/Neary, Peter: P.T. McGrath’s 1918 Account of Newfoundland’s Part in the Great War, in: Newfoundland and Labrador Studies 29/2 (2014), p. 279. See also the Regiment’s history at http://www.rnfldr.ca/history.aspx and Cramm, Richard: The First Five Hundred, New York 1921; reissued in 2015 by Boulder Publications, with an introduction by Mike O’Brien.

- ↑ Roberts, Edward: How Newfoundlanders Got the Baby Bonus, St. John’s 2013, p. 49; Frost, Sydney: A Blue Puttee at War: The Memoir of Captain Sydney Frost, MC, St. John’s 2014, pp. 21-23; O’Brien, Mike: Out of a Clear Sky: The Mobilization of the Newfoundland Regiment, 1914-1915, in: Newfoundland and Labrador Studies 22/2 (2007), pp. 412-13; and Mail and Advocate 5 November 1914.

- ↑ Roberts, How Newfoundlanders 2013, pp. 49-52; and Evening Telegram 15, 18, 20 February 1930.

- ↑ Frost, Blue Puttee 2014, pp. 65-67.

- ↑ O’Brien, Out of a Clear Sky 2007, p. 416; and Bert Dicks to the Mail and Advocate 14 November 1914. Dicks wrote to a friend in St. John’s that “we have had our khaki uniforms issued and the bunch look two hundred per cent better.”

- ↑ Facey-Crowther, David R. (ed.): Lieutenant Owen William Steele of the Newfoundland Regiment, Montreal & Kingston 2002, pp. 16-17, 19 and 30.

- ↑ Parsons, Andrew D.: Morale and Cohesion in the Royal Newfoundland Regiment, 1914-18. M.A. thesis, Memorial University 1995, pp. 77-94.

- ↑ See, for example, Morry, Christopher J.A.: When the Great Red Dawn is Shining: Howard L. Morry’s Memoirs of Life in the Newfoundland Regiment, St. John’s 2014, p. 151.

- ↑ Cadigan, Sean: Death on Two Fronts: National Tragedies and the Fate of Democracy in Newfoundland, 1914-34, Toronto 2013, pp. 80-81; Lind, Francis T.: The Letters of Mayor Lind: Newfoundland’s Unofficial War Correspondent, 1914-1916, St. John’s 2001, reprint of 1919 edition with an introduction by Peter Neary; and the Lester Barbour letters available at http://collections.mun.ca/cdm/landingpage/collection/barbour (retrieved 5 January 2016).

- ↑ Frost, Blue Puttee 2014, pp. 88-89.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 90-91.

- ↑ Nicholson, G.W.L.: The Fighting Newfoundlander: A History of the Royal Newfoundland Regiment, Montreal & Kingston 2006, reprint of 1964 edition, pp. 155-192.

- ↑ Frost, Blue Puttee 2014, p. 119.

- ↑ Baker and Neary, P.T. McGrath’s 1918 Account 2014, p. 281.

- ↑ Frost, Blue Puttee 2014, p. 127 and Lackenbauer, P. Whitney: War, Memory and the Newfoundland Regiment at Gallipoli, in: Newfoundland and Labrador Studies 15/2 (1999), pp. 176-214.

- ↑ Frost, Blue Puttee 2014, pp. 143, 147-153 and Harding, Robert: Glorious Tragedy: Newfoundland’s Cultural Memory of the Attack at Beaumont Hamel, 1916-1925, in: Newfoundland and Labrador Studies 21/1 (2006) 3-40.

- ↑ Gogos, Frank: The Royal Newfoundland Regiment in the Great War: A Guide to the Battlefields and Memorials of France, Belgium, and Gallipoli, St. John's 2015, p. 121; and Cadigan, Death 2013, p. 331, n. 3. Casualty figures have never been accurately calculated.

- ↑ See, for example, Morry, Great Red Dawn 2014, pp. 136-137, 151.

- ↑ Baker and Neary, P.T. McGrath’s 1918 Account 2014, pp. 283-284.

- ↑ Harding, Glorious Tragedy 2006, pp. 8-9; Cadigan, Death 2013, pp. 134-139. Another senior British military officer told them soon after 1 July, “Well done Newfoundlanders. You have proved equal to the best.”

- ↑ On the conscription debate see, O’Brien, Patricia Ruth: The Newfoundland Patriotic Association: The Administration of the War Effort, 1914-1918. M.A. thesis, Memorial University 1981, pp. 319-329 and Martin, Chris: The Right Course, the Best Course, the Only Course: Voluntary Recruitment in the Newfoundland Regiment, 1914-1918, in: Newfoundland and Labrador Studies 24/1 (2009), pp. 71-89.

- ↑ Frost, Blue Puttee 2014, p. 222; and Nicholson, Fighting Newfoundlander 2006, pp. 310-317.

- ↑ Baker and Neary, P.T. McGrath’s 1918 Account 2014, pp. 283-284.

- ↑ Nicholson, Fighting Newfoundlander 2006, p. 315.

- ↑ Gogos, The Royal Newfoundland Regiment 2015, pp. 130-133.

- ↑ Baker and Neary, P.T. McGrath’s 1918 Account 2014, pp. 283-284.

- ↑ Frost, Blue Puttee 2014, p. 267; Gogos, The Royal Newfoundland Regiment 2015, pp. 187-204; and Nicholson, Fighting Newfoundlander 2006, pp. 266-268.

- ↑ Frost, Blue Puttee 2014, pp. 269-270.

- ↑ Gogos, The Royal Newfoundland Regiment 2015, p. 249.

- ↑ Facey-Crowther, Steele 2002, p. 10; and Frost, Blue Puttee 2014, pp. 272-281.

- ↑ Evening Advocate 16 Jan. 1918; Frost, Blue Puttee 2014, pp. 304-315; and Gogos, The Royal Newfoundland Regiment 2015, p. 21.

- ↑ Cadigan, Death 2013, pp. 160-161, 166-158, 172-175.

- ↑ Evening Advocate 29 May 1918; and Martin, The Right Course 2009, p. 78.

- ↑ Gogos, The Royal Newfoundland Regiment 2015, pp. 231-306.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 31 and Sharpe, Christopher A.: The ‘Race of Honour’: An Analysis of Enlistments and Casualties in the Armed Forces of Newfoundland: 1914-1918, in: Newfoundland and Labrador Studies 4/1 (1988), pp. 27-55.

- ↑ Frost, Blue Puttee, p. 408.

- ↑ Browne, Gary F.: Forget-me-Not: Fallen Boy Soldiers, Royal Newfoundland Regiment, World War One, St. John’s 2010, pp. 2-5.

- ↑ Frost, Blue Puttee 2014, pp. 439-440.

- ↑ See http://collections.mun.ca/cdm/landingpage/collection/cns_veteran (retrieved 5 January 2016).

- ↑ See Harding, Robert: The Role of the Great War Veterans’ Association of Newfoundland, 1918 to 1925. Hons. Diss., Department of History, Memorial University 2003; http://www.heritage.nf.ca/first-world-war/articles/commemorations-overseas.php (retrieved 5 January 2016); and Baker, Melvin and Neary, Peter: Gerald Joseph Whitty, in: Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, Toronto 2005, available at http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio.php?BioId=42117 (retrieved 5 January 2016).

- ↑ Facey-Crowther, Steele 2002, p. 10.

- ↑ See http://whereoncetheystood.org/ (retrieved 5 January 2016).

- ↑ Baker, Melvin and Neary, Peter: A ‘real record for all time’: Newfoundland and Great War Official history, in: Newfoundland and Labrador Studies 27/1 (2012), pp. 5-32.

- ↑ Facey-Crowther, Steele 2002, p. 10.

Selected Bibliography

- Baker, Melvin / Neary, Peter: 'A real record for all time'. Newfoundland and Great War official history, in: Newfoundland and Labrador Studies 27/1, 2012, pp. 5-32

- Cave, Joy B.: What became of Corporal Pittman?, Portugal Cove 1976: Breakwater Books.

- Feehan, James P. (ed.): Essays on the Great War. Papers published in Newfoundland and Labrador Studies, St. John's 2014: Faculty of Arts Publications, Memorial University of Newfoundland.

- Gogos, Frank / MacDonald, Morgan: Known unto God. In honour of Newfoundland's missing during the Great War, St. John's 2009: Breakwater Books.

- Gwyn, Sandra: Tapestry of war. A private view of Canadians in the Great War, Toronto 1992: HarperCollinsPublishers.

- McAllister, Anthony: The greatest gallantry. The Newfoundland Regiment at Monchy-le-Preux, April 14, 1917, St. John's 2011: DRC Publishing.

- O'Gorman, Bill: Lest we forget. The life and times of veterans from the Port au Port Peninsula, World War I, West Bay Centre 2009: Transcontinental Print.

- Parsons, W. David: Pilgrimage. A guide to the Royal Newfoundland Regiment in World War One, St. John's 1994: Creative Publishers.

- Patey, Francis: Veterans of the North, St. John's 2003: Creative Publishers.

- Riggs, Bertram G. (ed.): Grand Bank soldier. The war letters of Lance Corporal Curtis Forsey, St. John's 2007: Flanker Press.

- Stacey, A. J. / Stacey, Jean Edwards: Memoirs of a Blue Puttee. The Newfoundland Regiment in World War One, St. John's 2002: DRC Publishers.